Post-injection quadriceps contracture is a rare entity nowadays with post-operative multiple complications, in our case, we did horizontal z quadricepsplasty with no post-operative complications.

Dr. Samrat S Sahoo, Department of Orthopaedics, AIIMS Kalyani, Nadia, West Bengal, India. E-mail: samrat.sahoo@gmail.com

Introduction: Post-injection quadriceps contracture (PIQC) is a rare disease entity nowadays as the route of injection has been changed from intramuscular to intravenous. Many types of quadricepsplasty were described with different complications.

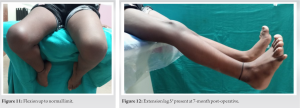

Case Report: A 5-year 6-month-old boy was presented with right quadriceps contracture which was managed with distal horizontal Z quadricepsplasty and immobilization with a slab in an early post-operative day. After 4 weeks of static quadriceps exercise, then range of motion exercises was started.

Conclusion: PIQC is a rare entity and can be treated successfully with horizontal z plasty. Knee range of movement can be achieved without any significant extension lag and skin complications.

Keywords: Quadricepsplasty, quadriceps contracture, horizontal z plasty, post-injection, children.

Post-injection quadriceps contracture (PIQC) becomes a forgotten entity or rare nowadays. We have not found any recent publications regarding this disease condition. Previously, it was more common due to intramuscular injection of different drugs in children [1]. In young children, thigh injection is preferred as their gluteal muscles are not so developed. Hence, there are increased chances of sciatic nerve palsy [2]. Now, due to the increase use of intravenous routes for injectable drugs, this disease becomes rare. Reasons for contracture are such as congenital/idiopathic, infective, post-surgical, ischemic myositis, post-traumatic myositis, and injection myositis. There may be associated conditions such as genu recurvatum, habitual dislocation patella, patella alta, or anterior tibial subluxation or dislocation [3].

A 5-year 6-month-old boy had a history of being unable to fold his right knee for the past 3 years. The patient had a history of some difficulty in right knee folding or squatting since 1 year of age. The deformity was progressive and pain-free. There was no history of trauma or infection. The patient had a history of some immunization injections on the right thigh by the age of 9 months. After 2 months, the patient developed a nodule-like firm swelling at the injection site. There were no discharge, no ulceration, and no fever. The patient was advised hot cold compression and local ointment application by the immunization nursing care provider. The patient then gradually developed a decrease in knee flexion. There was difficulty in squatting and cross-legged sitting also. The patient had normal lumbar lordosis, skin creases over the knee were decreased compared to normal knee, affected knee was in an extended position. There was knee hyperextension around 10°, passive knee flexion was a jog, and quadriceps were taught and cord like. There was no genu recurvatum, subluxation of the tibia, genu valgum, or habitual dislocation of the patella. Thigh wasting was present. Ely’s test was negative. No other congenital anomaly was present. Neurological examination (motor, sensation, reflexes) was normal. There were no X-ray changes, no patellar hypoplasia, no flattening of the femoral condyle, and no degeneration of knee joints. In magnetic resonance imaging, pathology was seen in the lower end of the quadriceps tendon which was a small fusiform swelling. However, it was not specified which tendons were mostly involved. After a thorough discussion with the guardian and planning, the patient was then proceeded for operative management like horizontal distal quadricepsplasty. Anesthesia team preferred caudal block plus general anesthesia.

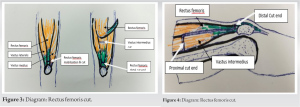

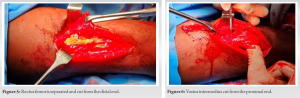

Distal thigh longitudinal anterolateral approach was used for the patient. Then rectus femoris was isolated from vastuses (Fig. 1).

There are literature that mentioned different types of quadricepsplasty with different complications and comorbidities. At present, with some modification of distal quadricepsplasty described by Payr [5, 6] and by Thompson [7, 8], most surgeries are performed. Although with these procedures, knee extension lag or wound dehiscence complications are noted. According to Burnei et al., Payr-Thompson technique is more effective [9] for quadricepsplasty. Jackson and Hutton mentioned that distal quadricepsplasty had extensor lag and the best outcome was found with the proximal release [10]. Running and standing up from a sitting position needs 110° knee flexion and for walking 60–70° [11, 12].

Although rare nowadays, we should not forget the entity of PIQC, as some vaccination yet has to be given intramuscularly. After thorough examination and investigation, we should decide on the surgical procedures. Horizontal distal quadricepsplasty having fewer complications such as excessive extension lag or restricted flexion can be used routinely although further study is needed. Strict physiotherapy and restricted knee motion are also important for children in early post-operative days.

Proper precautionary steps should be taken for intramuscular injection for the pediatric age group. PIQC being a rare disease, we should consider this as one of the differential diagnoses for any quadriceps contracture in children. Surgeons should focus on surgical steps and post-operative rehabilitation to avoid complications.

References

- 1.Gunn DR. Contracture of the quadriceps muscle. A discussion on the etiology and relationship to recurrent dislocation of the patella. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1964;46:498-502. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Robert H. Sciatica paralysis after intramuscular injection in children. About a series of 29 cases. Rev Pediatr 1983;10:569-75. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Williams PF. Quadriceps contracture. J Bone Joint Surg 1968;15-B:278-84. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fiogbe MA, Gbenou AS, Magnidet ER, Biaou O. Distal quadricepsplasty in children: 88 cases of retractile fibrosis following intramuscular injections treated in Benin. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res 2013;99:817-22. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baciu C. Chirurgia si Protezarea Aparatului Locomotor. Bucuresti: Editura Medicala; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Payr E. Advanced experience in mobilization of stiff joints [in German]. Arch Chir (Berlin) 1914;106:235-50. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nicoli EA. Quadricepsplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1963;45B:483-90. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thompson TC. Quadricepsplasty to improve knee function. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1944;26A:366-79. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Burnei G, Naeagoe P, Margineanu BA, Dan DD. Treatment of severe iatrogenic quadriceps retraction in children. J Pediatr Orthop B 2004;13:254-8. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jackson AM, Hutton PA. Injection -induced contractures of the quadriceps in childhood. A comparison of proximal release and distal quadricepsplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1985;67:97-102. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kettelkamp DB, Johnson RJ, Smidt GL, Chao EY, Walker M. An electrogoniometric study of knee motion in normal gait. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1970;52:775-90. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kettelkamp DB, Nasca R. Biomechanics and knee joint replacement arthroplasty. Clin Orthop 1973;94:8-14. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carro Alonso B, Villavieja Atance JL, Fernández Gómez JA, Sainz Martínez JM. Progressive fibrosis of the quadriceps muscle. An Pediatr (Barc) 2006;65:638-9. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Soumah MT, Sylla AI, Toure MR, Camara T, Kama ML, Diallo MB, et al. Quadriceps fibrosis following intramuscular injections into the thigh: Apropos of 92 cases at the Ignace Deen Central University Hospital in Conakry. Med Trop (Mars) 2003;63:49-52. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mukherjee PK, Das AK. Injection fibrosis in the quadriceps femoris muscle in children. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1980;62:453-6. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nemoto F. Pathogenesis of quadriceps contracture in children and adolescence (author’s transl). Nihon Seikeigeka Gakkai Zasshi 1980;54:15-31. [Google Scholar]