A multidisciplinary management approach is crucial for timely diagnosis and optimum treatment of pyoderma gangrenosum after TKA.

Dr. Vikram I Shah, Chairman and Managing Director, Shalby Multispeciality Hospital, Ahmedabad, Gujarat, India. E-mail: arthroplasty1@shalby.in

Introduction: Pyoderma gangrenosum (PG) following a primary total knee arthroplasty (TKA) surgery is extremely rare, with very few cases reported in the literature.

Case Report: We report our clinical experience of a 65-year-old female who developed PG following a primary TKA surgery. Corticosteroids and local wound care with vacuum-assisted closure dressing helped achieve rapid improvement in the wound condition.

Conclusion: Post-surgical PG in TKA can be challenging with limited evidence for its definitive treatment. A high degree of suspicion and a multidisciplinary management approach will help in the timely diagnosis and optimization of treatment for this condition.

Keywords: Wound breakdown, pyoderma gangrenosum, knee, total knee arthroplasty.

Pyoderma gangrenosum (PG) is a rare inflammatory disorder of unknown etiology causing skin necrosis and ulceration [1]. This can present secondary to trauma or surgical procedures and is often mistaken for wound infections and necrotizing fasciitis [2]. Although the pathogenesis of PG is still unclear, it has been associated with dysregulation of polymorphonuclear cell activity, increased activation of the complement pathway, and the excess release of stimulating cytokines resulting in skin lesions [1]. PG is rare, with a worldwide incidence of 3–10 patients per million population per year [2]. Post-surgical PG can pose a challenge to the surgeon due to a lack of awareness and a clinical similarity with wound sepsis or infection, which can lead to delayed diagnosis and incorrect treatment. Although surgical site PG has been well described in the literature following breast and abdomen surgery [2], reports of its occurrence and management in patients undergoing orthopedic surgical procedures are limited, with only 30 cases reported worldwide [3]. Furthermore, PG following total knee arthroplasty (TKA) is extremely rare, with very few cases reported in the literature [4-12]. In this case report, we describe the presentation and management of PG following primary TKA surgery in a female patient, with a review of literature on PG following TKA surgery.

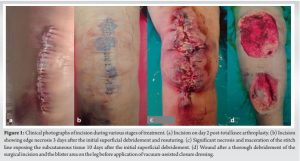

A 62-year-old female came to us with right knee pain secondary to advanced tricompartmental osteoarthritis, for which a cruciate-substituting TKA was performed under spinal anesthesia. The patient was overweight (body mass index 29.3 kg/m2), hypertensive, with normal blood sugar levels and a glycosylated hemoglobin level of 5.8. The patient did not have any history of chronic dermatological or inflammatory conditions like rheumatoid arthritis and was never on disease-modifying anti-rheumatoid drugs or steroids. The patient had undergone a tubal ligation procedure, cataract surgery, and renal stone surgery in the last 10 years, all of which had a complete and uneventful recovery. The TKA surgery was performed under strict aseptic precautions, with the surgical site covered with an iodine-impregnated incision drape (Ioban 2™, 3M Health Care, India) in an operation theater (OT) equipped with laminar airflow, and the surgical team used body exhaust helmet suits during surgery. The wound was closed in layers after proper hemostasis without a drain and covered with a sterile dressing. The total duration of surgery was approximately 45 mins, and the patient was administered 2 doses of intravenous (IV) antibiotics perioperatively and oral antibiotics for the next 48 h. The patient was discharged after 3 uneventful days and a clean incision during the wound check (Fig. 1a). The patient reported persistent soakage 6 days after TKA surgery, and wound inspection at the outpatient clinic showed oozing and redness around the incision, indicating a superficial wound infection. A superficial debridement was performed in the OT, and stay sutures were applied. The daily wound check for the next 3 days after debridement showed a healthy skin margin with no wound oozing. Culture samples taken during debridement revealed a methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus epidermidis (MRSE) infection, and IV Linezolid and Levofloxacin were administered based on the sensitivity report. Resuturing was performed on the 4th day after the debridement (or 10 days post-TKA) in OT, and a check dressing the next day revealed a 2 cm skin edge maceration of the middle 1/3rd of the stitch line with a blister of around 6 cms on the anterior aspect of the middle 1/3rd of the leg (Fig. 1b).

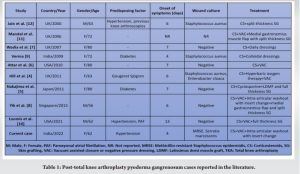

Post-surgical PG is extremely rare following TKA, with only 9 cases reported in the literature since 2000 (Table 1).

In conclusion, post-surgical PG in a TKA patient can be challenging in terms of diagnosis and treatment. The surgeon should have a high degree of suspicion, and a multidisciplinary management approach with the orthopedic surgeon, dermatologist, or rheumatologist, and the plastic surgeon can help in timely diagnosis and optimum treatment.

A multidisciplinary management approach with the orthopedic surgeon, dermatologist or rheumatologist, and plastic surgeon can help in the timely diagnosis and optimum treatment of PG after TKA.

References

- 1.Flora A, Kozera E, Frew JW. Pyoderma gangrenosum: A systematic review of the molecular characteristics of disease. Exp Dermatol 2022;31:498-515. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tolkachjov SN, Fahy AS, Cerci FB, Wetter DA, Cha SS, Camilleri MJ. Post-operative pyoderma gangrenosum: A clinical review of published cases. Mayo Clin Proc 2016;91:1267-79. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ebrad S, Severyns M, Benzakour A, Roze B, Derancourt C, Odri GA, et al. Pyoderma gangrenosum after orthopaedic or traumatologic surgery: A systematic revue of the literature. Int Orthop 2018;42:239-45. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hill DS, O’Neill JK, Toms A, Watts AM. Pyoderma gangrenosum: A report of a rare complication after knee arthroplasty requiring muscle flap cover supplemented by negative pressure therapy and hyperbaric oxygen. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg 2011;64:1528-32. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nakajima N, Ikeuchi M, Izumi M, Kuriyama M, Nakajima H, Tani T. Successful treatment of wound breakdown caused by pyoderma gangrenosum after total knee arthroplasty. Knee 2011;18:453-5. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Attar S, Spangehl MJ, Casey WJ, Smith AA. Pyoderma gangrenosum complicating bilateral total knee arthroplasty. Orthopedics 2010;33:441. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wadia F, Malik MH, Porter ML. Post-operative wound breakdown caused by pyoderma gangrenosum after bilateral simultaneous total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2007;22:1232-5. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yik JH, Bigliardi PL, Sebastin SJ, Cabucana NJ, Venkatachalam I, Krishna L. Pyoderma gangrenosum mimicking early acute infection following total knee arthroplasty. Ann Acad Med Singapore 2015;44:150-1. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Verma SB. Atypical pyoderma gangrenosum following total knee replacement surgery: First report in dermatologic literature. An Bras Dermatol 2009;84:689-91. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Loomis R, Merrit M, Aleshin MA, Graw G, Lee G, Graw B. Pyoderma gangrenosum after bilateral total knee arthroplasty. Arthroplast Today 2021;11:73-9. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mandal A, Addison P, Stewart K, Neligan P. Vacuum-assisted closure therapy in pyoderma gangrenosum. Eur J Plast Surg 2006;28:529-31. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jain A, Nanchahal J, Bunker C. Pyoderma gangrenosum occurring in a lower limb fasciocutaneous flap--a lesson to learn. Br J Plast Surg 2000;53:437-40. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Teagle A, Hargest R. Management of pyoderma gangrenosum. J R Soc Med 2014;107:228-6. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maverakis E, Ma C, Shinkai K, Fiorentino D, Callen JP, Wollina U, et al. Diagnostic criteria of ulcerative pyoderma gangrenosum: A Delphi consensus of international experts. JAMA Dermatol 2018;154:461-6. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Almeida IR, Coltro PS, Gonçalves HO, Westin AT, Almeida JB, Lima RV, et al. The role of negative pressure wound therapy (NPWT) on the treatment of pyoderma gangrenosum: A systematic review and personal experience. Wound Repair Regen 2021;29:486-94. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee S, Lee JY, Ju HJ, Lee JH, Koh SB, Bae JM, et al. Association of all-cause and cause-specific mortality risks with pyoderma gangrenosum. JAMA Dermatol 2023;159:151-9. [Google Scholar]