Surgical treatment should be offered to all young patients with pectoralis major tear irrespective of level of activity and conservative management should be reserved for geriatric patients with low activity levels and medically unfit patients.

Dr. Avinashdev Devmani Upadhyay, Department of Orthopaedics, K. B BHABHA Municipal General Hospital, Mumbai Maharashtra, India. E-mail: dravinashupadhyay92@gmail.com

Introduction: Pectoralis major (PM) muscle ruptures are uncommon injuries. 365 cases of PM injury have been reported, with 75% occurring in the past 20 years; of these, 83% were a result of indirect trauma, with 48% occurring during weight-training activities. We report a case of PM rupture in a 35-year-old gym trainer who presented to our hospital with pain and weakness in his right shoulder after injury while doing bench press treated with Primary repair using Ethibond 5–0 and endobuttons who had excellent function outcome and no evidence of complication at 2 years follow-up.

Case Report: A 35-year-old gentleman presented to the emergency department after experiencing sudden pain in his right chest and a tearing sensation while bench pressing (approximately 100 kg). He is a gym trainer who exercised with a lot of weight and denied any steroid use. Upon clinical examination, he had ecchymosis and loss of shoulder contour, bulking over the right chest. The shoulder range of movement was preserved, with weakness of adduction and internal rotation. Plain radiographs of the right shoulder were obtained which was normal. A magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan revealed a PM rupture at the insertion site with retraction and the patient was treated with primary repair of the PM. The patient exhibited satisfactory shoulder range of movement by 3 months follow-up and achieved his pre-injury strength by 6 months follow-up.

Conclusion: PM ruptures are uncommon injuries that commonly occur in young men between 20 and 40 years old. Patients usually present with shoulder pain and weakness after a strenuous activity and a diagnosis can be made with MRI. Hence, surgical treatment should be offered to all young patients with PM tear irrespective of level of activity and conservative management should be reserved for geriatric patients with low activity levels and medically unfit patients.

Keywords: Pectoralis major, muscle rupture, surgical treatment, bench press, primary repair.

Pectoralis major (PM) muscle ruptures are uncommon injuries [1]. 365 cases of PM injury have been reported, with 75% occurring in the past 20 years; of these, 83% were a result of indirect trauma, with 48% occurring during weight-training activities [1]. Although the condition is well known among orthopedic surgeons, due to its rarity, a high degree of clinical suspicion is required for the diagnosis not to be missed. We report a case of PM rupture in a 35-year-old gym trainer. He presented to our hospital with pain and weakness in his right shoulder following an injury incurred while doing a bench press. The patient was treated with a primary repair using Ethibond 5–0 and endobuttons. He demonstrated excellent functional outcomes and showed no evidence of complications at the 2-year follow-up.

A 35-year-old gentleman presented to the emergency department after experiencing sudden pain in his right chest, accompanied by a tearing sensation while bench pressing (approximately 100 kg). He is a gym trainer who exercised with a lot of weight training and denied any steroid use. Upon clinical examination, he had ecchymosis and loss of shoulder contour, bulking over the right chest. The shoulder range of movement was limited by pain.

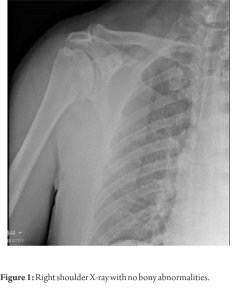

The patient had a Medical Research Council (MRC) scale of 3 out of 5 in shoulder adduction and an MRC scale of 4 out of 5 in shoulder internal rotation. There was no associated neurovascular injury. Plain radiographs of the right shoulder were obtained which were normal (Fig. 1). A magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan revealed a PM rupture at the insertion site (TIETEN TYPE 3D) (Table 1) with retraction (Fig. 2) and the patient was treated with primary repair of the PM.

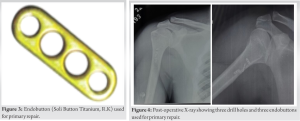

The deltopectoral approach was used. Cephalic veins retracted laterally. Insertion site of PM freshened, retracted PM tendon held with allis forceps, and three Krakow sutures placed from proximal to distal with Ethibond 5–0. Three drill holes of 4 mm each were made at the proposed insertion site proximal to distal. The suture ends looped through the endobutton (Fig. 3). The endobutton (Soli Button Titanium, R.K) was inserted vertically through drilled holes (Fig. 4) and sutures were pulled causing the endobutton to flip and then were secured with knots using appropriate tension with the shoulder in adduction and internal rotation. Post-operatively the patient was immobilized for 4 weeks. Gradual strengthening exercises were started at 6 weeks.

At 3 months follow-up patient was allowed to go to the gym for weight training and by 6 months patient had achieved his pre-injury status (Fig. 5).

Related anatomy

PM is composed of two heads: The clavicular head originates from the medial half of the clavicle, and it is shorter. The sternal head originates from the second to sixth ribs, the costal margin of the sternum, and the aponeurosis of the external oblique [2]. The two heads fuse to a broad tendon at the intertubercular sulcus. Specifically, they both insert through an anterior and posterior layer at the lateral lip of the bicipital groove [2]. PM’s main functions are adduction and internal rotation of the arm, while it also provides some flexion [2, 3].

Classification

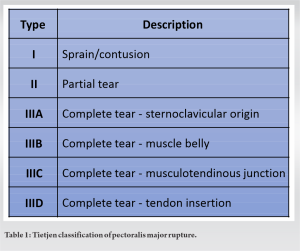

The classification system for pectoralis major ruptures encompasses three primary categories: Sprain/contusion, partial tear, and complete tear, representing a progression from mild to severe injury. Complete tears are further differentiated based on their anatomic location, which can be at the Sternoclavicular origin, within the muscle belly, at the musculotendinous junction, or at the tendon insertion. (Table 1)

Pathogenesis

PM tears occur during excessive tension or, less commonly, after a direct trauma [4]. Specifically, rupture occurs when tension is applied to an eccentrically contracting muscle [2, 3]. This is the case of maximal contraction when the arm is externally rotated, extended, and abducted [4]. Less commonly, rupture may result from a direct blow [3, 4]. Muscle structure allows for maximum muscle power production but has also as a consequence disproportionately high fiber excursion in the inferior sternocostal head. This phenomenon is believed to be the explanation behind PM rupture during mechanical stress in the disadvantageous position (e.g., bench press) [2], which was also the mechanism of PM rupture in the presented case

Presentation

Classic history includes sudden onset of pain, accompanied by a “pop” sensation [1, 5]. Upon examination, there is usually bruising and swelling of the affected anterolateral chest wall [1, 2]. Tenderness over the humeral insertion is common [2, 5]. Loss of the axillary fold can be seen, although this finding may be obscured by the tissue swelling [1, 5]. Resisted adduction is helpful in testing strength as muscle power may be decreased [1, 5]. Full-thickness tears have a characteristic “gap.” However, the axillary fold and not the fascial sheath should be palpated [2]. Upon examination, our patient had evidence of PM rupture with ecchymosis over the right shoulder area and loss of shoulder contour, as well as bulking over the right chest. Although no gap could be palpated and the shoulder range of movement was preserved, muscle power in arm adduction and internal rotation was significantly decreased.

Diagnosis

Initial imaging investigation should include plain radiographs to exclude concomitant bone injuries [3, 6]. Pain radiographs may be useful only in rare cases of bone avulsion [1, 3]. This occurs in 2–5% of the cases [2, 3]. Ultrasonography (USG) is an adjunct when MRI cannot be performed [1]. Its usefulness relies on the fact that it is a low-cost and available imaging modality. However, USG is an operator-dependent modality and is shown to produce false-negative results. MRI scan is the investigation of choice. It can distinguish between partial and full-thickness tears thus helping with surgical planning [1, 7]. In our case, 48 h after the MRI revealed an intramuscular complete rupture of the sternal head of the PM. Early diagnosis and early surgery are safe, effective, and reproducible results with better function and cosmesis. The selection of available treatments has included both surgical and conservative methods [8-10]. Hence, in our opinion, operative treatment should be offered to all young patients with PM tears irrespective of the level of activity. There is a dearth of information on the treatment of pectoralis ruptures. Surgical treatment through anatomic repair is typically recommended in situations of entire or near-total injury since conservative treatment may result in loss of strength in the shoulder flexion, internal rotation, and adduction. If left untreated, the anterior axilla’s contour may be upset, leading to an unsatisfactory cosmetic outcome. The anatomic repair often yields good results; but, to restore the upper limb’s normal function and strength, careful surgical skill and extensive rehabilitation are required [11]. A ruptured PM muscle can be repaired surgically using a variety of methods, such as end-to-end repair and anchor suture reinforcement when a portion of the tendon is still attached to the humerus [12]. Suturing a tendon directly into drilled holes at the insertion location using non-absorbable sutures [8], to two rows of drill holes, or the trough and any neighboring holes created and using cancellous screws and washers or staples [13].

For chronic ruptures, reconstruction with the use of autografts or allografts is described [1, 2].

Specific repair technique depends on the site of rupture: Musculotendinous junction injuries are repaired by direct suturing, while avulsion injuries are anatomically reduced and internally fixated [3].

Literature generally shows that acute repairs are easier and lead to improved results [2].

In chronic settings, adhesions between ruptured muscle and chest wall may complicate the procedure [3].

Conservative management is reserved for the elderly population or individuals who do not wish or are not medically fit for surgery [1, 2]. The protocol involves sling immobilization with immediate passive exercises and unrestrictive activity allowed after 2–3 months [1, 2]. Contact sports should only be initiated after 5–6 months [2].

Recent studies show that the power of adduction and internal rotation is permanently diminished when conservative management is chosen [3].

In our case, the patient underwent right PM tendon repair 7 days after the injury. On follow-up in the 2nd and 6th post-operative week, no post-operative complication was evident, and the patient was referred for physiotherapy. The patient demonstrates almost normal muscle power (MRC scale 5 out of 5) in all shoulder movements after 6 months of follow-up.

PM ruptures are uncommon injuries and commonly occur in young men between 20 and 40 years. Patients usually present with shoulder pain and weakness after a strenuous activity and a diagnosis can be made with MRI. Surgical intervention should be contemplated for young patients experiencing complete tears of the PM, regardless of their activity level. Conversely, conservative management is advisable for geriatric patients with low activity levels or those deemed medically unfit.

Primary Repair using Ethibond and endobutton is a cost-effective method and allows for adequate tissue-to-bone healing for surgical management of PM tear. Indeed, surgical intervention should be considered for young patients afflicted with complete tears of the PM, irrespective of their level of physical activity.

References

- 1.ElMaraghy AW, Devereaux MW. A systematic review and comprehensive classification of pectoralis major tears. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2012;21:412-22. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Butt U, Mehta S, Funk L, Monga P. Pectoralis major ruptures: A review of current management. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2015;24:655-62. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haley CA, Zacchilli MA. Pectoralis major injuries: Evaluation and treatment. Clin Sports Med 2014;33:739-56. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schepsis AA, Grafe MW, Jones HP, Lemos MJ. Rupture of the pectoralis major muscle. Outcome after repair of acute and chronic injuries. Am J Sports Med 2000;28:9-15. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wolfe SW, Wickiewicz TL, Cavanaugh JT. Ruptures of the pectoralis major muscle. An anatomic and clinical analysis. Am J Sports Med 1992;20:587-93. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Petilon J, Carr DR, Sekiya JK, Unger DV. Pectoralis major muscle injuries: Evaluation and management. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2005;13:59-68. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee SJ, Jacobson JA, Kim SM, Fessell D, Jiang Y, Girish G, et al. Distal pectoralis major tears: Sonographic characterization and potential diagnostic pitfalls. J Ultrasound Med 2013;32:2075-81. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hanna CM, Glenny AB, Stanley SN, Caughey MA. Pectoralis major tears: Comparison of surgical and conservative treatment. Br J Sports Med 2001;35:202-6. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Scott B, Wallace WA, Barton MA. Diagnosis and assessment of pectoralis major rupture by dynamometry. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1992;74:111-3. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Metzger PD, Bailey JR, Filler RD, Waltz RA, Provencher MT, Dewing CB. Pectoralis major muscle rupture repair: Technique using unicortical buttons. Arthrosc Tech 2012;1:e119-25. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aärimaa V, Rantanen J, Heikkilä J, Helttula I, Orava S. Rupture of the pectoralis major muscle. Am J Sports Med 2004;32:1256-62. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Orava S, Sorasto A, Aalto K, Kvist H. Total rupture of pectoralis major muscle in athletes. Int J Sports Med 1984;5:272-4. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Egan TM, Hall H. Avulsion of the pectoralis major tendon in a weight lifter: Repair using a barbed staple. Can J Surg J Can Chir 1987;30:434-5. [Google Scholar]