A compartment syndrome is a real orthopedic emergency. Early recognition and treatment will save the affected limb. Late diagnosis, or poor treatment, can end in disaster. Late diagnosis, or poor management of compartment syndrome, is a frequent cause for claims by lawyers for clinical negligence, in some societies.

Dr. Mansi Zied, Department of Orthopedic Surgery, IBN EL JAZZAR University Hospital, Kairouan, Tunisia. E-mail: doc.zm@htmail.fr

Introduction: Compartment syndrome as a complication during intramedullary nailing of closed tibia fractures was first documented as early as 1980.

Case Report: We report a case of a 19-year-old young man victim of a road accident (motorcycle accident) causing an uncomplicated closed fracture of 2 bones of the left leg. The patient underwent centromedullary nailing of the tibia. The evolution was marked by the early onset of an acute and serious compartment syndrome.

Conclusion: The first symptom of compartment syndrome is pain regardless of the severity of the trauma. The diagnosis is clinical and is generally confirmed by measuring the pressure in the muscle compartment. The treatment is fasciotomy.

Keywords: Compartment syndrome, leg, nailing tibia, fasciotomy.

Compartment syndrome is defined as an increase in intramuscular pressure that compromises the perfusion of the contents of the muscle compartment in question. Compartment syndrome as a complication during intramedullary nailing of closed tibia fractures was first documented as early as 1980. Acute compartment syndrome of the leg is the most common. This study seeks to examine this potentially debilitating complication, emphasizing the crucial significance of prompt diagnosis and effective management of compartment syndrome following fracture fixation.

This is a case of a 19-year-old young man victim of a motorcycle accident causing an uncomplicated closed fracture of 2 bones of the left leg (Fig. 1). He was given a centromedullary nailing of the tibia after 3 h of the initial accident. The intervention was carried out with a tourniquet inflated to 350 mmHg and lasted 45 min.

After the operation, the leg was elevated with continuous icing and the patient was put on anticoagulant. The evolution was marked by the appearance of unbearable pain after 6 hours of the operation, with the progressive appearance of paresthesia and poorly systematized tingling in the leg. The patient was put under strong analgesics and anti-inflammatory drugs intravenously with elevation of the lower limb and continuous icing but without improvement with accentuation of pain, crises of agitation, and the installation of a partial sensory-motor deficit of the external popliteal sciatic nerve (hypoesthesia of the dorsal aspect of the 1st interdigital space and partial dorsiflexion deficit of the ankle).

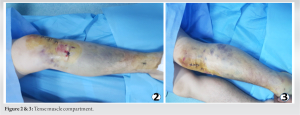

On palpation, the muscle compartments were tense, but the equipment needed to measure intramuscular pressure was not available (Fig. 2 and 3).

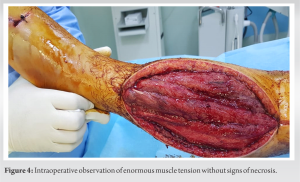

In view of this scenario, a fasciotomy of all the muscular compartments of the leg has been indicated. The patient was taken to the operating room 7 h after the first surgery and an open fasciotomy of the muscle compartments was performed through an anterolateral approach to the left leg with the intraoperative observation of enormous muscle tension without signs of necrosis and immediate retraction of the edges (with a gap between the 2 banks at 7 cm) (Fig. 4).

The wound was covered with tulle gras. The patient was taken back to the operating room every 48–72 h to clean, bring the edges together, and make a sterile dressing until the complete closure of the wound after 21 days (Fig. 5-7).

Skin closure was achieved after 21 days without resorting to the use of a negative pressure system (vacuum-assisted closure [VAC] therapy). The patient retained a partial sensory-motor deficit of the external popliteal sciatic nerve (partial deficit of the foot elevators and hypoesthesia of the dorsal face of the 1st commissure). This deficit was recovered after 6 months after a well-conducted rehabilitation protocol.

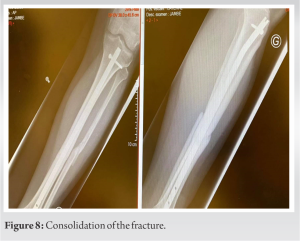

On the bone level, the evolution was made toward pseudarthrosis which required surgical revision after 6 months (reaming and re-nailing with a larger diameter nail) with consolidation of the fracture in the third post-operative month (Fig. 8).

Open fasciotomy caused esthetic sequelae (Fig. 9).

The diagnosis of compartment syndrome is essentially clinical, although it is often confirmed by measuring intramuscular pressure [1]. The diagnostic and therapeutic delay being the main prognostic factor, it is essential not to neglect the first clinical signs [2]. The first clinical sign is pain that is unusual in relation to the causative factor and the increased need for analgesic [3]. The pain is present at rest and increases over time as well as passive mobilization soliciting the tendons of the muscles of the compartment in question [3]. Early on, the patient may also experience paresthesia or hypoesthesia (he complains of tingling or numbness) [2]. Particular attention should be paid to patients who have undergone spinal anesthesia or locoregional anesthesia, in whom the only early clinical sign is the palpation of tense muscle compartments. These patients should be closely monitored when they have had high-risk surgery (leg or foot surgery) and should not hesitate to measure the intramuscular pressure in the slightest doubt and repeatedly [4]. The same applies to sedated or intubated patients, multiple trauma patients with distracting pain, or patients whose cognitive functions are impaired (confusion, dementia, disability, etc.) [5]. Late, in the stage of potentially irreversible prolonged ischemia, the compressed muscles gradually no longer contract and pass from paresis to paralysis, the limb is white and cold, and the pulses have disappeared [2]. Despite the arrival of less invasive measurement methods (see below), direct measurement of IMP remains the reference with a sensitivity of 94%, a specificity of 98%, a positive predictive value of 93%, and a negative predictive value of 99% [6]. The measurement must be taken in the 4 compartments of the leg (anterior, lateral, superficial, and deep posterior), ideally at the level of the proximal third or in the 5 cm around the possible fracture, in different places and repeatedly if necessary [7]. The general annual incidence of compartment syndrome is 7.3/105 in men with an average age of 30 years; it is 0.7/105 in women with an average age of 44 years. Fractures are the main cause (69% of cases), mainly the tibia (36%) [8]. The second most common cause is soft tissue contusion without associated fracture (23%), followed by crush syndrome (7.9%). The most frequent circumstance of occurrence is a road accident (29%) followed by a sports injury (20%) [2]. In the leg, it is the anterior compartment (anterior tibial muscle, extensor hallucis longus, and toes) which is the narrowest and most frequently affected [9]. All treatments, orthopedic or surgical, can be complicated by a syndrome acute [10, 11]. Nailing with reaming was particularly critical. However, a meta-analysis finds no more compartment syndrome in the case of nailing without reaming, even if the difference is not significant [12]. In the same spirit, prospective randomized studies report an incidence similar [13, 14]. Recordings of intramedullary pressures showed peaks when reducing the fracture, when using horizontal pull, when boring, and during nailing itself [15-17]. To reduce the risk of compartment syndrome, nailing of the dangling leg is currently recommended. Minimal reaming without strict adaptation of the nail to the medullary canal also reduces the risk [18]. In all cases, when compartment syndrome is suspected, it will first be necessary to remove extrinsic compression elements [8]: Clothing, bandage, and cast, to avoid raising the limb. In fact, the elevation does not reduce intramuscular pressure but decreases mean arterial pressure and therefore perfusion and to correct any hypovolemia to maintain mean arterial pressure. Take care to maximize the hydration of the patient with crush syndrome [4]. For the treatment of acute compartment syndrome of the leg, it is recommended to decompress the 4 compartments by two cutaneous incisions [8], even if the pressure measurement is not positive for all the compartments. The first anterolateral incision is made midway between the tibial crest and the fibula, 5 cm distal to the fibular head, and up to 5 cm proximal to the lateral malleolus. It then makes it possible to incise longitudinally the anterior compartment and the lateral compartment [19]. The second posteromedial incision is made 2 cm behind the medial edge of the tibia, decompresses the superficial posterior compartment containing the triceps surae, the soleus must be partially disinserted proximally to reach the deep compartment after incising the deep fascia at its medial edge, to avoid the posterior tibial pedicle. The structures at risk are the nerve and the saphenous vein [10]. During fasciotomy, muscle viability must be checked and any necrotic tissue must be carefully debrided, otherwise, the infection may be encouraged [20]. At the end of the operation, you should obviously not try to close the skin under tension. The wounds are covered with tulle gras. The patient should be taken back to the operating room every 48–72 h to clean, debride, and trim if necessary [4]. As soon as the distance between the edges reaches 1 cm, the skin can be closed. If the edges of the skin cannot be brought together, the use of a negative pressure system (VAC therapy) may be necessary before covering with a skin graft [21]. Any diagnostic and therapeutic delay generates sequelae: Persistence of sensory symptoms (paresthesia, hypoesthesia, anesthesia); − a muscle that has been ischemia, even if it has not completely necrosed, may partially lose its function (paresis). The necrotic muscle should be excised carefully so as not to promote infection or increase tissue damage [22]. Open fasciotomy always causes esthetic sequelae. Fasciotomy performed late, insufficient debridement, or neglected wound care can promote infection. Myositis can progress to osteomyelitis. Past infection or extensive necrosis can ultimately lead to amputation and even death.

Compartment syndrome results in an increase in pressure in an inextensible aponeurotic compartment which induces muscle ischemia in the compartment. The first symptom is pain regardless of the severity of the trauma. The diagnosis is clinical and is generally confirmed by measuring the pressure in the muscle compartment. The treatment is fasciotomy. A compartment syndrome is a real orthopedic emergency. Late diagnosis, or poor treatment, can end in disaster. Early recognition and treatment will save the affected limb.

The surgical release of the affected muscle compartments, by incising the skin and fascia over the whole length of the compartment is known as fasciotomy. This is the only treatment for a confirmed, or strongly suspected, muscle compartment syndrome. It is essential to perform this as an emergency procedure and certainly no later than 6 h from the onset of the condition. Basically, as soon as possible, it is a true surgical emergency.

References

- 1.Du W, Hu X, Shen Y, Teng X. Surgical management of acute compartment syndrome and sequential complications. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2019;20:98. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Raza H, Mahapatra A. Acute compartment syndrome in orthopedics: Causes, diagnosis, and management. Adv Orthop 2015;2015:543412. [Google Scholar]

- 3.McQueen MM, Christie J, Court-Brown CM. Acute compartment syndrome in tibial diaphyseal fractures. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1996;78:95-8. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roger DJ, Tromanhauser S, Kropp WE, Durham J, Fuchs MD. Compartment pressures of the leg following intramedullary fixation of the tibia. Orthop Rev 1992;21:1221-5. [Google Scholar]

- 5.McQueen MM, Court-Brown CM. Compartment monitoring in tibial fractures. The pressure threshold for decompression. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1996;78:99-104. [Google Scholar]

- 6.McQueen MM, Duckworth AD, Aitken SA, Court-Brown CM. The estimated sensitivity and specificity of compartment pressure monitoring for acute compartment syndrome. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2013;95:673-7. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Staudt JM, Smeulders MJ, van der Horst CM. Normal compartment pressures of the lower leg in children. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2008;90:215-9. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guo J, Yin Y, Jin L, Zhang R, Hou Z, Zhang Y. Acute compartment syndrome. Medicine (Baltimore) 2019;98:e16260. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khoshhal KI, Alsaygh EF, Alsaedi OF, Alshahir AA, Alzahim AF, Al Fehaid MS. Etiology of trauma-related acute compartment syndrome of the forearm: A systematic review. J Orthop Surg Res 2022;17:342. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Letenneur J. Leg Compartment Syndromes. In: Conference of SOFCOT. Teaching Notebooks. Paris: French Scientific Expansion; 1999. p. 185-98. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tischenko GJ, Goodman SB. Compartment syndrome after intramedullary nailing of the tibia. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1990;72:41-4. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bhandari M, Guyatt GH, Tong D, Adili A, Shaughnessy SG. Reamed versus nonreamed intramedullary nailing of lower extremity long bone fractures: A systematic overview and meta-analysis. J Orthop Trauma 2000;14:2-9. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Finkemeier CG, Schmidt AH, Kyle RF, Templeman DC, Varecka TF. A prospective, randomized study of intramedullary nails inserted with and without reaming for the treatment of open and closed fractures of the tibial shaft. J Orthop Trauma 2000;14:187-93. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Larsen LB, Madsen JE, Høiness PR, Øvre S. Should insertion of intramedullary nails for tibial fractures be with or without reaming? A prospective, randomized study with 3.8 years’ follow-up. J Orthop Trauma 2004;18:144-9. [Google Scholar]

- 15.McQueen MM, Gaston P, Court-Brown CM. Acute compartment syndrome. Who is at risk. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2000;82:200-3. [Google Scholar]

- 16.McQueen MM, Christie J, Court-Brown CM. Compartment pressures after intramedullary nailing of the tibia. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1990;72:395-7. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moed BR, Thorderson PK. Measurement of intracompartmental pressure: A comparison of the slit catheter, side-ported needle, and simple needle. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1993;75:231-5. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gaebler C, Berger U, Schandelmaier P, Greitbauer M, Schaunwecker HH, Applegate B, et al. Rates and odds ratios for complications in closed and open tibial fractures treated with unreamed, small diameter tibial nails: A multicenter analysis of 467 cases. J Orthop Trauma 2001;15:415-23. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pearse MF, Harry L, Nanchahal J. Acute compartment syndrome of the leg. BMJ 2002;325:557-8. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kalyani BS, Fisher BE, Roberts CS, Giannoudis PV. Compartment syndrome of the forearm: A systematic review. J Hand Surg Am 2011;36:535-43. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morykwas MJ, Argenta LC, Shelton-Brown EI, McGuirt W. Vacuum-assisted closure: A new method for wound control and treatment: Animal studies and basic foundation. Ann Plast Surg 1997;38:553-62. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reverte MM, Dimitriou R, Kanakaris NK, Giannoudis PV. What is the effect of compartment syndrome and fasciotomies on fracture healing in tibial fractures? Injury 2011;42:1402-7. [Google Scholar]