While traditionally associated with tuberculosis and immunocompromised individuals, the vague symptomatology and pathogenesis make psoas abscess a challenging clinical diagnosis in the pediatric population. A high level of clinical suspicion, timely imaging studies, and targeted treatment are essential for its management.

Dr. Harsh Parekh, Department of Orthopedics, K.B Bhabha Municipal General Hospital, Mumbai, Maharashtra, India. E-mail: harshparekh01@hotmail.com

Introduction: Pyogenic psoas abscess (PPA) is a rare but severe condition. Previously linked to tuberculosis, it’s now seen with diverse causes. This case report details the diagnosis and management of PPA in a healthy Indian child, initially suspected of having hip issues.

Case Report: A 5-year-old girl was brought for pain in her right hip and lower back, and fever for 3 days. She was irritable and unable to walk. She was febrile (101°F), irritable, and toxic with her right lower limb flexed 30° at the hip with all its movements restricted and painful. Inguinal lymph nodes were palpable. Blood tests showed elevated white blood cell count (18,000 × 109/L) and inflammatory markers, with a negative Mantoux test. Radiographs of the lumbosacral spine were normal. Magnetic resonance imaging showed a large abscess in the right psoas and iliacus muscles, measuring 6.8 × 3.3 × 3 cm. She underwent open drainage through a retroperitoneal approach, and samples were sent for bacteriological analysis. The wound was irrigated and closed over a drain. Post-operatively, she received Linezolid being culture positive for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Her pain reduced by the 3rd day and she was discharged with oral antibiotics. She walked at 6 weeks and was symptom-free on follow-up.

Conclusion: This case highlights the crucial need to consider PPA in children showing hip pain, limping, and infection signs. Due to its subtle presentation and similarity to septic arthritis, high suspicion is essential. Timely imaging and proper treatment, such as drainage and antibiotics, can ensure positive results.

Keywords: Pediatric, pyogenic psoas abscess, immunocompetent, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, hip pain, surgical drainage, antibiotic therapy.

Pyogenic psoas abscess (PPA) is a rare but serious condition characterized by the accumulation of pus in the psoas muscle compartment. While historically associated with tuberculosis (TB), especially in regions with high TB prevalence, such as India, PPA is increasingly recognized as having varied etiologies [1,2]. In this case report, we describe the presentation, diagnosis, and management of a PPA in an immunocompetent Indian child who was initially thought to have hip pathology.

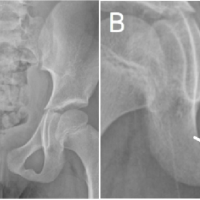

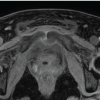

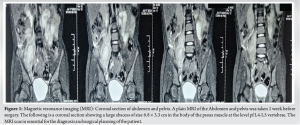

A 5-year-old girl was brought to the emergency room of the hospital by her mother with complaints of pain in her right hip and lower back, accompanied by fever for 3 days. The child had been irritable and reluctant to walk. There was no history of trauma, surgery, or prior illnesses. She had not been exposed to anyone with TB, nor did she experience evening fevers or night sweats. Her vaccinations were all up to date. On examination, she presented with her right lower limb flexed at the hip and knee, demonstrating reluctance to bear weight and walking with a limp. Active extension of the limb was not possible, and attempts to passively extend the hip caused significant pain. No visible swellings or tenderness were noted over the hip, abdomen, or lower back. All movements at the hip joint were restricted and painful, with a fixed flexion deformity of 30°. Palpable inguinal lymph nodes were observed. The child was febrile with a temperature of 101°F and appeared irritable and toxic. Hematological tests revealed an elevated white blood cell (WBC) count of 18,000, with increased polymorphonuclear leukocytes. Inflammatory markers such as erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP) were also significantly elevated. A Mantoux test yielded a negative result. Radiographs of the lumbosacral spine and both hips did not reveal any fractures, soft tissue abnormalities, or signs of spinal TB. Following an urgent magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the pelvis and lumbar spine, a large abscess was found in the right psoas and iliacus muscles, extending along the iliopsoas tendon insertion into the lesser trochanter. The abscess measured approximately 6.8 × 3.3 × 3 cm (Fig. 1 and 2).

The patient underwent open drainage through a retroperitoneal approach. During the procedure, purulent fluid mixed with blood was drained, and samples were sent for bacteriological analysis. The wound was thoroughly irrigated, and a negative suction drain was placed (Fig. 3).

Post-operatively, the patient received empirical antibiotics (Ceftriaxone), which were later adjusted based on culture results showing Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), requiring intravenous linezolid for 2 weeks, followed by oral antibiotics for 4 weeks. The patient’s condition improved steadily, with reduced pain by the third post-operative day, and she regained hip mobility in the subsequent weeks. Hematological markers of inflammation also receded in the post-operative period. Domiciliary rehabilitation was initiated, and the patient regained her ambulatory status within 6 weeks. At follow-up, following completion of the antimicrobial regimen, symptoms and signs had resolved.

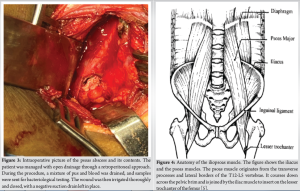

The iliopsoas compartment is extraperitoneal, consisting of the iliacus and psoas muscles. The psoas muscle arises from the transverse processes and lateral borders of the T12-L5 vertebrae, coursing down across the pelvic brim to insert on the lesser trochanter of the femur. It is the primary flexor of the hip and trunk [3,4].

Anatomical relations of the muscle include:

- Anteriorly: The gastrointestinal and urinary tracts, the inferior vena cava, the abdominal aorta, and iliac lymph nodes.

- Posteriorly: The quadratus lumborum muscle and the transverse spinous processes.

- In the thigh: The iliopsoas forms part of the floor of the femoral triangle (Fig. 4).

A breach in the retroperitoneal fascial planes by infective, hemorrhagic, or neoplastic processes can pre-dispose the iliopsoas to direct contact with infectious material from adjacent structures [5]. Its rich blood supply makes it susceptible to hematogenous spread of infection [6,7]. Psoas abscesses (PA) may be classified as primary or secondary depending on the etiology. Primary abscesses arise de novo without the presence of an infective focus elsewhere in the body or through hematogenous or lymphatic routes from a distant, occult source. They may be associated with immunosuppression, diabetes mellitus, renal failure, or HIV [7-9]. Trauma and hematoma formation may pre-dispose to the development of a primary psoas abscess [10-12]. Occurrence in children tends to be primarily de novo, as opposed to secondary spread from contagious infectious processes seen in adults [5, 11-13]. The most common organism in a primary psoas abscess is S. aureus (88.4% of cases), with other pathogens including Streptococcus (4.9%) and Escherichia coli (2.8%) [13]. Other organisms such as Bacteroides spp., Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Enterococcus faecalis, and Pepto streptococcus have also been reported. MRSA has been documented on a case-by-case basis [14]. A case series by López et al. in 2009 found that of ninety-three confirmed microbial causes, twenty-three were due to S. aureus, of which only one was MRSA [15]. Current literature from Western countries shows that hematogenous spread from the gastrointestinal tract is the most common cause of idiopathic psoas abscess [16], while studies from tertiary care centers in North India and South India indicate that M. tuberculosis is the predominant cause of idiopathic psoas abscess [1,2], highlighting geographic variations. Secondary abscesses are more common in adults over 50 years old and occur due to direct spread of infections from adjacent sites, such as the gastrointestinal tract (E. coli and other Enterobacteriaceae), genitourinary tract, vertebral column, and hip joint (M. tuberculosis) [13,17]. The most common cause in this group is Crohn’s disease [18]. Given that no secondary source of infection was identified in our patient, her psoas abscess is likely of primary etiology. The typical age of presentation in children is between 5 and 9 years, with a higher prevalence in males [8,14]. The classical triad of fever, limp, and back pain is present in fewer than 30% of patients [19]. Some patients may also experience associated abdominal, genitourinary, spinal complaints, thigh or loin pain (or mass), and fixed flexion deformity of the affected side [8,14,19,20]. Hip flexion deformity can be a helpful differentiating feature, as 96% of patients with iliopsoas abscesses hold the hip in flexion to relieve pain. Our patient presented with an insidious onset of non-specific symptoms, including fever, hip pain, limping, and inability to bear weight, prompting a provisional diagnosis of septic arthritis. Both septic arthritis and psoas abscess can present with limp and hip pain as well as systemic features, such as fever, making differentiation challenging. The presence of abdominal pain may be more suggestive of a psoas abscess [21]. The diagnosis of septic arthritis is particularly favored when patients meet the Kocher criteria, as seen in our patient, who exhibited all four criteria (non-weight bearing, temperature >38.5°C, ESR >40 mm/h, and WBC >12,000 cells/mm³). Some studies have even described psoas abscess as a consequence of septic arthritis, although others could not establish this correlation [22]. Due to the variability in clinical presentation, imaging studies are crucial for distinguishing iliopsoas abscesses from other inflammatory processes, such as septic arthritis [10,23,24]. Imaging is performed for both confirming the diagnosis and planning management [11,25].

- Plain abdominal X-ray: May reveal an abnormal psoas shadow, soft tissue mass, or subluxation of the involved joint [11,25].

- Ultrasonography: Preferred as the first-line investigation due to its affordability, availability, and lack of radiation exposure [26,27]. It may demonstrate a hypoechoic mass suggestive of a psoas abscess and can also show hip effusions in the case of arthritis, but it cannot identify the cause of the abscess [11,25,28,29].

- Computed tomography (CT) scan: CT with contrast helps accurately diagnose a psoas abscess and aids in therapeutic percutaneous drainage (PCD) [30-32].

- MRI: Assists in surgical planning by delineating the zone of involvement [33].

Conventional treatment options for iliopsoas abscesses in pediatric patients typically involve appropriate antibiotic administration (empiric followed by targeted therapy) along with abscess drainage, either surgically or through radiologic guidance [8,11,12,18]. Surgical intervention is often necessary in cases where there is a large abscess or failure of conservative management. Open drainage is traditionally performed through a retroperitoneal approach, which provides direct access to the abscess while minimizing complications related to surrounding structures [34-36]. Alternatively, PCD is increasingly utilized due to its minimally invasive nature and favorable outcomes in select cases [4-6]. In our patient, the abscess was successfully drained through the retroperitoneal approach, coupled with appropriate antimicrobial therapy tailored to the cultured organism. The choice of linezolid for MRSA was crucial, highlighting the need for sensitivity-based treatment in the face of rising antibiotic resistance. The post-operative course was uneventful, and the patient exhibited significant clinical improvement, regaining functional mobility within weeks.

This case underscores the importance of considering PPA in pediatric patients presenting with hip pain, limping, and systemic signs of infection. Given the often-subtle presentations and overlapping symptoms with septic arthritis, a high index of suspicion is vital. Prompt imaging studies and appropriate management, including drainage and targeted antibiotic therapy, can lead to successful outcomes.

The article highlights the importance of early diagnosis, targeted treatment, and management in pediatric cases of PPA. A high index of clinical suspicion is essential, as PA are commonly associated with tuberculosis and immunocompromised individuals in the subcontinent. Due to overlap with the clinical presentation of conditions, such as septic arthritis and non-specific symptoms such as hip pain, limping, and systemic signs of infection, prompt imaging with MRI or CT scans is crucial for accurate diagnosis and timely intervention. Early intervention, including surgical drainage and culture-guided antibiotic therapy, is essential, particularly for addressing antibiotic-resistant pathogens, such as MRSA. The case underscores the need for targeted treatments to improve patient outcomes.

References

- 1.Gupta S, Suri S, Gulati M, Singh P. Ilio-psoas abscesses: Percutaneous drainage under image guidance. Clin Radiol 1997;52:704-7. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 2.Rodrigues J, Iyyadurai R, Sathyendra S, Jagannati M, Prabhakar Abhilash K, et al. Clinical presentation, etiology, management, and outcomes of iliopsoas abscess from a tertiary care center in South India. J Fam Med Prim Care 2017;6:836. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 3.Standring S. Gray’s anatomy : The anatomical basis of clinical practice. 41st ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Limited; 2016. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 4.Moriarty CM, Baker RJ. A pain in the psoas: Groin injury in a collegiate football athlete. Sports Health Multidiscipl Approach 2016;8:568-72. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 5.Muttarak M, Peh WC. CT of unusual iliopsoas compartment lesions. Radiographics 2000;20 Spec No:S53-66. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 6.Taiwo B. Psoas abscess: A primer for the internist. South Med J 2001;94:2-5. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 7.Mallick IH, Thoufeeq MH, Rajendran TP. Iliopsoas abscesses. Postgrad Med J 2004;80:459-62. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 8.Walsh TR, Reilly JR, Hanley E, Webster M, Peitzman A, Steed DL. Changing etiology of iliopsoas abscess. Am J Surg 1992;163:413-6. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 9.Mückley T, Schütz T, Kirschner M, Potulski M, Hofmann G, Bühren V. Psoas abscess: The spine as a primary source of infection. Spine 2003;28:E106-13. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 10.Song J, Letts M, Monson R. Differentiation of psoas muscle abscess from septic arthritis of the hip in children. Clin Orthop 2001;391:258-65. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 11.Gubbay AJ, Isaacs D. Pyomyositis in children. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2000;19:1009-12; quiz 1013. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 12.Okan F, Ince Z, Coban A, Can G. Neonatal psoas abscess simulating septic arthritis of the hip: A case report and review of the literature. Turk J Pediatr 2009;51:389-91. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 13.Franco-Paredes C, Blumberg HM. Psoas muscle abscess caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Staphylococcus aureus: Case report and review. Am J Med Sci 2001;321:415-7. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 14.Ricci MA, Rose FB, Meyer KK. Pyogenic psoas abscess: Worldwide variations in etiology. World J Surg 1986;10:834-42. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 15.López VN, Ramos JM, Meseguer V, Pérez Arellano JL, Serrano R, Ordóñez MA, et al. Microbiology and outcome of iliopsoas abscess in 124 patients. Medicine (Baltimore) 2009;88:120-30. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 16.Tabrizian P, Nguyen SQ, Greenstein A, Rajhbeharrysingh U, Divino CM. Management and treatment of iliopsoas abscess. Arch Surg Chic Ill 1960 2009;144:946-9. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 17.Santaella RO. Primary vs secondary iliopsoas abscess: Presentation, microbiology, and treatment. Arch Surg 1995;130:1309. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 18.Mynter H. Acute psoitis. Buffalo Med Surg J 1881;21:202-10. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 19.Chern CH, Hu SC, Kao WF, Tsai J, Yen D, Lee CH. Psoas abscess: Making an early diagnosis in the ED. Am J Emerg Med 1997;15:83-8. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 20.Procaccino JA, Lavery IC, Fazio VW, Oakley JR. Psoas abscess: Difficulties encountered. Dis Colon Rectum 1991;34:784-9. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 21.Karlı A, Belet N, Danacı M, Avcu G, Paksu Ş, Köken Ö, et al. Iliopsoas abscess in children: Report on five patients with a literature review. Turk J Pediatr 2014;56:69-74. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 22.Santili C, Júnior WL, Goiano EO, Lins RA, Waisberg G, Braga SD, et al. Limping in children. Rev Bras Ortop 2009;44:290-8. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 23.Larcamon J, Juanco G, Alvarez L, Pebe F. Psoas abscess as a chicken pox complication. Arch Argent Pediatría 2010;108:e86-8. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 24.Wang E, Ma L, Edmonds EW, Zhao Q, Zhang L, Ji S. Psoas abscess with associated septic arthritis of the hip in infants. J Pediatr Surg 2010;45:2440-3. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 25.Tong CW, Griffith JF, Lam TP, Cheng JC. The conservative management of acute pyogenic iliopsoas abscess in children. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1998;80:83-5. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 26.Malhotra R, Singh KD, Bhan S, Dave PK. Primary pyogenic abscess of the psoas muscle. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1992;74:278-84. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 27.Gerzof SG, Robbins AH, Birkett DH, Johnson WC, Pugatch RD, Vincent ME. Percutaneous catheter drainage of abdominal abscesses guided by ultrasound and computed tomography. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1979;133:1-8. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 28.Yowler CJ, Beam TE. Psoas abscess. Mil Med 1988;153:641-2. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 29.Gonzalez Moran G, Garcia Duran C, Albiñana J. Imaging on pelvic pyomyositis in children related to pathogenesis. J Child Orthop 2009;3:479-84. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 30.Lee JK, Glazer HS. Psoas muscle disorders: MR imaging. Radiology 1986;160:683-7. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 31.Pombo F, Martín-Egaña R, Cela A, Díaz JL, Linares-Mondéjar P, Freire M. Percutaneous catheter drainage of tuberculous psoas abscesses. Acta Radiol Stockh Swed 1987 1993;34:366-8. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 32.Mueller PR, Ferrucci JT, Wittenberg J, Simeone JF, Butch RJ. Iliopsoas abscess: Treatment by CT-guided percutaneous catheter drainage. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1984;142:359-62. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 33.Garner JP, Meiring PD, Ravi K, Gupta R. Psoas abscess - not as rare as we think? Colorectal Dis 2007;9:269-74. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 34.Toner E, Khaled A, Nakhuda Y, Mohil R. The limping child, a rare differential: Pyomyositis of the iliacus muscle -a case report. J Orthop Case Rep 2019;9:21-5. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 35.Dahami Z, Sarf I, Dakir M, Aboutaieb R, Bennani S, Elmrini M, et al. Treatment of primary pyogenic abscess of the psoas: Retrospective study of 18 cases. Ann Urol 2001;35:329-34. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 36.Yacoub WN, Sohn HJ, Chan S, Petrosyan M, Vermaire HM, Kelso RL, et al. Psoas abscess rarely requires surgical intervention. Am J Surg 2008;196:223-7. [Google Scholar | PubMed]