Primary malignant transformation in a giant cell tumor of bone is an extremely rare event, and its early diagnosis is pivotal in determining the appropriate management and prognosis.

Dr. Hazem Aboaid, Department of Internal Medicine, Kirk Kerkorian School of Medicine at UNLV, Las Vegas, Nevada, USA. E-mail: hazem.aboaid@unlv.edu

Introduction: Malignant giant cell tumor of bone (GCTB) is a very rare tumor, especially the primary type of it. We report a case of a young female who was diagnosed with a primary malignant giant cell tumor, in addition to a literature review of the previously reported cases. This case report aims to highlight the importance of high clinical suspicion and comprehensive workup to detect malignancy in giant cell tumors. We also review and add another case to the medical literature to help better understand the behavior of this rare tumor.

Case Report: A 30-year-old African American female presented with left knee pain. Imaging showed a cystic bone lesion of the left proximal tibia, which was found to be consistent with a primary malignant giant cell tumor on biopsy. She started neoadjuvant chemotherapy (methotrexate + doxorubicin + cisplatin); however, she only tolerated one cycle, and then she underwent a radical resection of the left proximal tibia with endoprosthetic reconstruction. She had multiple hospitalizations later, and she was found to have significant pulmonary and spinal metastasis. Eventually, she decided to resume chemotherapy due to her worsening disease, and she completed four cycles of doxorubicin and cisplatin with a recent plan to switch to regorafenib given her refractory disease.

Conclusion: Diagnosis of primary malignant GCTB can be very challenging. It is always important to seek an expert opinion given the rare nature of this tumor. Early detection is very important to establish the appropriate treatment.

Keywords: Giant cell tumor of bone, malignant, primary, secondary.

Giant cell tumor of bone (GCTB) is a known benign locally aggressive bone tumor that comprises approximately 5%–6% of all primary bone tumors [1,2]. Malignancy in giant cell tumors is generally rare (occurs in about 1.8% of cases) [1], especially primary malignant giant cell tumor (PMGCTB), which is considered to be extremely unusual, whereas secondary malignant giant cell tumor (SMGCTB) seems to be more common, and it usually presents following radiotherapy or surgical treatment [3]. GCTB can rarely metastasize in about 2% of the cases [4] with the lungs being the most common site [2], and even the benign version of GCTB has the ability to metastasize to the lungs too [1].

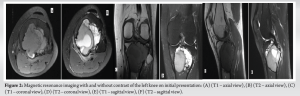

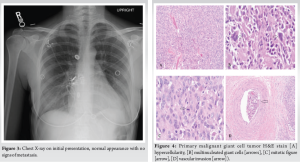

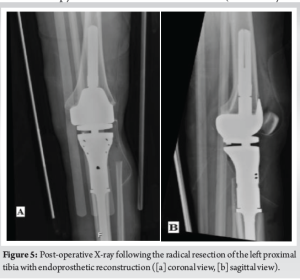

A 30-year-old African American female with no significant past medical history presented to the University Medical Center of Southern Nevada (UMC) with left knee pain for about 2 years that got worse over a few weeks. Before the presentation, she had an outpatient X-ray done showing a left knee bone lesion. She was also evaluated by an oncology outpatient, but no further workup was done by that time. On admission, the physical examination was only remarkable for tenderness over the left proximal tibia and mild pain with range of motion of the left knee. All vital signs were within normal limits. X-ray of the left knee (Fig. 1) showed a cystic bone lesion of the proximal tibia. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with and without contrast (Fig. 2) revealed a large complex intramedullary mass of the proximal tibia without evidence of cortical destruction or extraosseous soft-tissue invasion, and the findings were consistent with a giant cell tumor. Chest X-ray (Fig. 3) was unremarkable with no signs of metastasis. Computed tomography (CT) guided core needle biopsy of the lesion was done, histopathologic examination (Fig. 4) showed several cores of haphazardly arranged spindle to slightly epithelioid cells with enlarged irregular nuclei, mitotic figures were readily identified, immunohistochemical staining was positive for vimentin and CD68 with focal faint staining for smooth muscle actin. The aforementioned findings were all found to be consistent with a poorly differentiated neoplasm. The case was sent to the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, for expert opinion. The report came back with a diagnosis of a malignant GCTB. The H3 G34W mutation was positive which supported the diagnosis of a giant cell tumor, and the presence of several atypical cells and atypical mitosis and apoptosis supported the malignant version of the tumor. The patient was discharged from the hospital after the biopsy was done and recommended to follow up outpatient with medical and orthopedic oncology. She was started on a MAP regimen (methotrexate + Adriamycin “doxorubicin” + platinol “cisplatin”) and admitted to UMC twice for high-dose methotrexate. She completed only one round of chemotherapy and then opted to stop due to severe side effects. Four months following her initial presentation, she underwent an elective radical resection of the left proximal tibia with endoprosthetic reconstruction (Fig. 5), peroneal nerve neurolysis, and medial gastrocnemius rotational flap. Intraoperative biopsy was consistent with malignant giant cell tumor with margins negative for tumor or malignancy. CT chest without contrast 1 year following her initial presentation showed multiple scattered bilateral sub-6 mm pulmonary nodules; however, those nodules were not active on a positron emission tomography scan. Twenty months following her initial presentation, she presented to UMC with severe back pain radiating to her right lower extremity. CT of the lumbar spine without contrast showed an ill-defined partially sclerotic lesion involving the left L2 vertebral body with pathologic fracture with adjacent epidural hyperdense material concerning malignancy with epidural extension, there was severe spinal canal stenosis at the level of L2. MRI with and without contrast (Fig. 6) revealed a mass within the L2 and L3 vertebral bodies concerning osseous metastatic disease, in addition to enhancing mass within the spinal canal encasing the spinal nerve roots and possibly the conus medullaris from L1 through L3. She underwent a lumbar laminectomy of L1-3 for extradural tumor removal with instrumentation and fusion of L1-4. Intraoperative biopsy of the right L2 extradural mass was consistent with metastatic malignant giant cell tumor. No malignancy was identified on the posterior lamina’s biopsy. Repeat CT chest without contrast (Fig. 7) during the same hospitalization showed worsening metastatic disease with over 20 pulmonary nodules/masses noted. The patient had multiple hospitalizations afterward, most of them due to severe back and bilateral lower extremity pain, one of them being for worsening shortness of breath when she was found to have bilateral pulmonary emboli. Due to her worsening clinical status, she finally decided to restart chemotherapy. She was evaluated at USC (University of Southern California) for a second opinion, and she was started on the following regimen (cisplatin 75 mg/m2 IV on day 1 + doxorubicin 25 mg/m2 IV on days 1–3). She completed four rounds so far, and the most recent plan is to switch her to regorafenib given her refractory and metastatic disease.

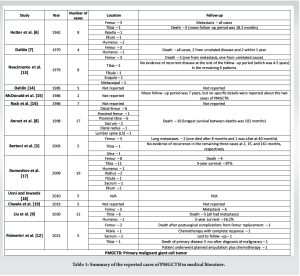

Malignant GCTB was first described in 1938 by Stewart et al. [5], then Hutter et al. [6] and Dahlin et al. [7] came and differentiated between two types of malignant GCTB, primary and secondary. Primary malignant GCTB is diagnosed when a sarcomatous tissue is seen next to areas of benign GCTB at the initial presentation, whereas secondary malignant GCTB is diagnosed when a sarcoma develops at the site of a previously treated (whether it is surgically or by radiation) benign GCTB. PMGCTB and SMGCTB both share similar clinical features with benign GCTB [1]. Pain and swelling are usually the most common presenting symptoms [8]. The femur and tibia (especially the distal femur and proximal tibia) are the most common sites of occurrence, as noted in Table 1. In our case, the tumor was in the proximal tibia, and pain was the chief complaint. Radiologically, malignant GCTB has a similar appearance on imaging to benign GCTB. They mostly present with an epiphyseal osteolytic bone lesion [9], as in our case. There are some other radiologic features that can suggest malignancy, such as invasion of the soft tissues and cortical lysis [8], which were not present in our case. Histologically, malignant GCTB is considered a high-grade sarcoma [2] with osteosarcoma, fibrosarcoma, and pleomorphic undifferentiated sarcoma being the most common pathologic types [1,2]. It can be challenging sometimes to differentiate between PMGCTB and giant cell-rich osteosarcoma, even though clinically the management is not different; however, H3 G34W mutation (a specific biomarker for GCTB which was positive in our case) can be useful in confirming the diagnosis of malignant GCTB and ruling out other giant cell-rich tumors of the bone [1]. Metastases have been reported in about 20%–60% of PMGCTB cases. Unfortunately, metastases in malignant GCTB have a worse prognosis compared to the ones in benign GCTB which are usually slow-growing with a better prognosis. Metastases are the leading cause of death in malignant GCTB [10]. In our case, the patient had significant pulmonary and vertebral metastases. Per the National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines [11], we generally follow the same treatment approach when we treat malignant GCTB or osteosarcoma. Therefore, our patient was started on neoadjuvant chemotherapy with MAP regimen upon diagnosis, but unfortunately, she only tolerated one cycle before having the surgery done; then, when she decided to resume chemotherapy, she was started on cisplatin + doxorubicin regimen at USC, which is another first-line therapy for osteosarcoma. Regorafenib is one of the second-line therapies for refractory or metastatic disease. The medical literature on malignant GCTB is generally scarce. A literature search through PubMed was performed to find the published cases of primary malignant GCTB. Table 1 summarizes all the studies and reported cases of PMGCTB that we have found [2,8,10,12].

Primary malignant GCTB is generally a rare condition, and diagnosis can be difficult due to multiple reasons, including the rarity of the condition, the similar clinical and radiologic presentation of the benign and malignant versions, in addition to the lack of clear diagnostic criteria. Therefore, physicians must always rule out malignancy when they diagnose a GCTB through a thorough histologic examination, as it will drastically change the management and prognosis.

The diagnosis and management of primary malignant GCTB are generally difficult, and it is always important to seek an expert opinion from a tertiary cancer center to establish the right diagnosis and treatment plan.

References

- 1.Ratnagiri R, Uppin S. H3F3A mutation as a marker of malignant giant cell tumor of the bone: A case report and review of literature. J Cancer Res Ther 2023;19:832-4. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 2.Palmerini E, Picci P, Reichardt P, Downey G. Malignancy in giant cell tumor of bone: A review of the literature. Technol Cancer Res Treat 2019;18:1533033819840000. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 3.Bertoni F, Bacchini P, Staals EL. Malignancy in giant cell tumor of bone. Cancer 2003;97:2520-9. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 4.Raskin KA, Schwab JH, Mankin HJ, Springfield DS, Hornicek FJ. Giant cell tumor of bone. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2013;21:118-26. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 5.Stewart FW, Coley BL, Farrow JH. Malignant giant cell tumor of bone. Am J Pathol 1938;14:515-36. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 6.Hutter RV, Worcester JN Jr., Francis KC, Foote FW Jr., Stewart FW. Benign and malignant giant cell tumors of bone. A clinicopathological analysis of the natural history of the disease. Cancer 1962;15:653-90. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 7.Dahlin DC, Cupps RE, Johnson EW Jr. Giant-cell tumor: A study of 195 cases. Cancer 1970;25:1061-70. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 8.Anract P, De Pinieux G, Cottias P, Pouillart P, Forest M, Tomeno B. Malignant giant-cell tumours of bone. Clinico-pathological types and prognosis: A review of 29 cases. Int Orthop 1998;22:19-26. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 9.Liu W, Chan CM, Gong L, Bui MM, Han G, Letson GD, et al. Malignancy in giant cell tumor of bone in the extremities. J Bone Oncol 2020;26:100334. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 10.Tahir I, Andrei V, Pollock R, Saifuddin A. Malignant giant cell tumour of bone: A review of clinical, pathological and imaging features. Skeletal Radiol 2022;51:957-70. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 11.National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) Guidelines for Bone Cancer Version 2. United States: NCCN; 2024. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 12.Palmerini E, Seeger LL, Gambarotti M, Righi A, Reichardt P, Bukata S, et al. Malignancy in giant cell tumor of bone: Analysis of an open-label phase 2 study of denosumab. BMC Cancer 2021;21:89 [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 13.Nascimento AG, Huvos AG, Marcove RC. Primary malignant giant cell tumor of bone: A study of eight cases and review of the literature. Cancer 1979;44:1393-402. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 14.Dahlin DC. Caldwell lecture. Giant cell tumor of bone: Highlights of 407 cases. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1985;144:955-60. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 15.McDonald DJ, Sim FH, McLeod RA, Dahlin DC. Giant-cell tumor of bone. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1986;68:235-42. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 16.Rock MG, Sim FH, Unni KK, Witrak GA, Frassica FJ, Schray MF, et al. Secondary malignant giant-cell tumor of bone. Clinicopathological assessment of nineteen patients. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1986;68:1073-9. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 17.Domovitov SV, Healey JH. Primary malignant giant-cell tumor of bone has high survival rate. Ann Surg Oncol 2010;17:694-701. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 18.Unni KK, Inwards C. Dahlin’s Bone Tumours: General Aspects and Data on 10165 Cases. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2010. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 19.Chawla S, Blay JY, Rutkowski P, Le Cesne A, Reichardt P, Gelderblom H, et al. Denosumab in patients with giant-cell tumour of bone: A multicentre, open-label, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol 2019;20:1719-29. [Google Scholar | PubMed]