The learning point is understanding the basic rehabilitation protocol for arthroscopic anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) reconstruction by knee arthroscopic surgeons. It also creates a rehabilitation program that will help rehabilitation specialists which highlight the recent advancements in the treatment program.

Dr. Sagar Deshpande, Department of Physiotherapy, 6th floor, D Y Patil Medical College building, Nerul, Navi Mumbai, India. E-mail: sagar.deshpande@dypatil.edu

Knee ligament injuries are common in sports players, military training, and high-demand professionals. In young, active patients, anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) restoration is usually recommended for regaining anterior-posterior and rotatory knee stability [1]. Due to the high incidence of ACL injury, it is important to design a rehabilitation program that targets a return to high-impact activities. The rehabilitation differs as per the graft used as well as the guidelines given by the arthroscopic surgeon; the functional demands of the patient should be considered while designing the rehabilitation program [2]. Rehabilitation holds an integral component of a complete recovery after ACL reconstruction (ACLR). Research shows that a standard prehabilitation following isolated ACL rupture holds importance in gaining the post-operative quadriceps and hamstring strength thereby, improving knee function as compared to those who do not receive prehabilitation [3]. Prehabilitation not only includes physiotherapy but also a multidisciplinary approach consisting of patient counseling by a psychologist and a nutritional advice [4]. The timing of surgical intervention of ACL also significantly affects the potential outcomes which substantially improve functional outcomes [5]. It is important to note the changing trend in rehabilitation based on criteria rather than duration which helps incorporate recent advancements [6]. To design a suitable treatment plan, the rehabilitation specialist must use their clinical assessment skills to plan evidence-based therapeutic approach. This rehabilitation protocol spans over a 6-month period and is divided into 7 timelines. Each timeline has goals and exercise suggestions for several domains: Range of motion (ROM) and flexibility, strength and endurance, proprioception, gait, and cardiovascular fitness. For healthy, active patients, full recovery from ligament surgeries typically takes 6–9 months. ACL rehabilitation may not require daily or weekly monitoring, but participation in physical therapy for education, evaluation, function monitoring, and treatment plan and its progression is essential to a successful and safe rehabilitation program. Through a five-phase rehabilitation program, the knee and lower extremities gradually experience an increase in the joint stress [7]. A long-term rehabilitation provides good joint stability and a return to pre-injury activity levels. Rehabilitation focuses on return to activities of daily living and sporting activity. When an athlete is cleared following physical therapy and returns to sports specific training despite of injury related deficits, the gap appears in rehabilitation. Thus, returning back to unrestricted play should be a gradual transition focusing on functional impairments. The prime focus of strength training should be proper movement patterns, strength endurance and postural stability [8]. The focus of the rehabilitation protocol mentioned below is from “acute care” to “return to sports.”

Goals

The goals of rehabilitation in the acute phase are as follows:

- Patient education about the importance of long-term rehabilitation ACLR

- Graft protection to prevent graft rupture

- Prevent post-operative complications such as deep vein thrombosis, iatrogenic nerve injury, and septic arthritis [9]

- Minimize pain and swelling

- Prevent extension lag at the knee and tightness of lower extremity muscles

- Improve knee ROM: 0–90°

- Prevent arthrogenic muscle inhibition and stimulate adequate quadriceps contraction

- Protective weight-bearing with a long knee brace and a walking aid.

Exercises

The following therapeutic exercises are recommended in the acute phase:

- Ankle pumps, elevation, and compression for swelling reduction

- Patellofemoral mobilization and tibiofemoral mobilization

- Static quadriceps sets for muscle activation

- Passive knee ROM (0–90°)

- Core stabilization and strengthening exercises with a primary focus on transversus abdominis activation and its progression

- Supine heel slides, wall slides, and hip mobility exercises like straight leg raises (SLR) in all planes

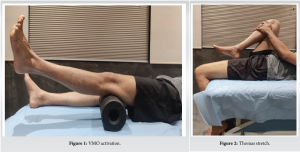

- Vastus medialis obliqus (VMO) activation to maintain terminal knee extension (fig 1)

- Supine gastrocnemius and soleus stretch to maintain muscle flexibility, iliopsoas stretch using unoperated leg knee flexion (Thomas position) – (fig 2)

- Prone hangs, if extension lag is present to promote end-range extension

- Soft tissue mobilization to quadriceps, hamstrings, and calf

- Hip strengthening: static gluteal sets to activate hip extensors, short hip flexor (iliopsoas) activation

- Upper extremity strengthening using weight cuffs, dumbbells, or therabands

- Sit-to-stand transfer training to start the protected weight-bearing activity.

Rehabilitative devices

- Cryotherapy for 15–20 min for swelling and pain reduction

- Neuromuscular electrical stimulation for adequate muscle contraction (fig 3)

- Continuous passive movement for the knee joint (0–70°).

Criteria for progression

- Minimal pain and swelling

- Absence of extension lag at the knee

- Knee ROM ≥90°

- Absence of antalgic gait

- SLR without extension lag.

Goals

The goals of rehabilitation in the sub-acute phase are as follows:

1. Continue graft protection

2. Improve neuromuscular control of the knee joint

3. Maintain knee ROM (0–110°) and improve muscle flexibility

4. Improve quadriceps and hamstring strength

5. Improve joint stability and knee proprioception

6. Bracing of the knee using a hinged knee brace

7. Initiate closed-chain and open-chain exercises to increase gradual joint loading

8. Progress with full weight-bearing gait training with or without walking aid; encourage heel-to-toe gait.

Exercises

The following therapeutic exercises are recommended in the sub-acute phase:

1. Continue acute-stage exercises

2. Active-assisted prone hamstring curls and standing hamstring curls after 4 weeks of rehabilitation to activate the knee flexors

3. Initiate gentle hamstring stretch to maintain its flexibility, posterior capsule stretch, and prone quadriceps stretch, Thomas stretch for iliopsoas, and iliotibial (IT) band stretch

4. Active VMO activation

5. Muscle energy technique to increase ROM

6. Retrograde-walking to strengthen hip and knee extensors

7. Static cycling without resistance for improving muscle endurance

8. Initiate step-up, step-down, and lateral step-up exercises (2–4 inch step) to increase joint stress

9. Supine bridging to stabilize and strengthen core and hip extensor muscles

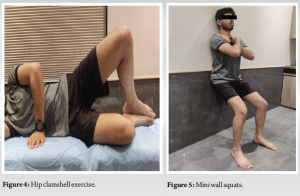

10. Hip clamshell exercise to activate gluteus medius and minimus (fig 4)

11. Hip abductor strengthening

12. Progression of transversus abdominis activation and core strengthening exercises

13. Multiple angle isometrics to quadriceps in sitting

14. Mini wall squats (0–45°) to strengthen quadriceps (fig 5)

15. Heel raises with support for gastrocnemius and soleus strengthening

16. Toes raises with support for ankle and foot dorsiflexor muscle strengthening

17. Balance training with a bilateral stance on an even surface.

Rehabilitative devices

1. Biofeedback/electrical stimulation to stimulate functional muscle activity

2. Aquatic therapy uses buoyancy of water to strengthen the muscles and aid in recovery [10]

3. Dry needling can be used to relieve myofascial pain syndrome post-surgery to reduce pain and muscle spasms [11]

4. Cupping therapy helps to relax the muscles by decreasing muscle tension [12]

5. Matrix rhythm therapy produces oscillations that help to regain normal cellular frequency.

Criteria for progression

1. No pain and swelling at the knee joint; no signs of active inflammation

2. Knee ROM ≥110°

3. Quadriceps strength >50% of the uninvolved side

4. Normal gait pattern

5. Presence of normal patella mobility

6. Full weight-bearing without a walking aid.

Goals

The goals of rehabilitation in the chronic phase are as follows:

1. Maintain and improve muscle flexibility

2. Improve motor control and knee joint stability

3. Maintain knee ROM (0–125°)

4. Improve core and lower limb muscle strength

5. Improve proprioception and balance

6. Full weight-bearing without walking aid (may or may not use hinged knee brace).

Exercises

The following therapeutic exercises are recommended in the chronic phase:

1. Continue phase 1 and phase 2 exercises

2. Initiate forward and lateral lunges for core stability and lower limb strengthening

3. Standing quadriceps stretch, IT band stretch/foam roller (fig 6)

4. Supine unilateral bridging

5. Wall squats (0–90o) to strengthen knee extensors. Maintain knee stability during wall squats to avoid unwanted joint loading

6. Step-up exercises (up to 8 inch)- (fig 7)

7. Obstacle walking for gait training

8. Static cycling with resistance for strength endurance training

9. Muscle energy technique to increase ROM

10. Seated leg extension (90°–45°) with weights or therabands for quadriceps strength (fig 8)

11. Leg presses focusing on knee extensor strengthening (45°–0)

12. Recumbent bicycling with mild resistance for knee extensors

13. Core strengthening

14. Balance training on an unstable surface; progress to single-leg balance training and balance with perturbations.

Rehabilitative devices

1. Blood flow restriction (BFR) training for muscle strengthening and hypertrophy

2. Aquatic therapy to accelerate the recovery process.

Criteria for progression

1. Absence of pain

2. Knee ROM: 120–130°

3. Quadriceps and Hamstring strength >70% of the uninvolved side

4. Able to jog or run

5. No compensation during a squat

6. Hop test >80% as compared to the uninvolved side

7. Unilateral stance for 20–30 s without support

8. Ascent and descent of stairs without pain and compensation.

Goals

The goals of rehabilitation in this phase are as follows:

1. Maintain knee proprioception and neuromuscular control

2. Maintain knee ROM (0–135°)

3. Improve lower limb muscle strength and endurance

4. Improve balance and coordination

5. Improve aerobic fitness

6. Initiate skill-specific training

7. Full weight-bearing (with or without neoprene sleeve).

Exercises

The following therapeutic exercises are recommended in this phase:

1. Warm up with 10 min of cycling to improve aerobic fitness and muscle endurance

2. Balance and proprioception training on an unstable surface (fig 9)

3. Step-ups and lateral step-ups (up to 12 inches)

4. Plyometric training for improving physical performance using variations in speed and forces with changing movements

5. Retrograde walking on a treadmill for balance and hip extensor training

6. Leg press (90°–0) with resistance for strengthening of lower limb muscles

7. Body weight squats for improving mobility and strengthening of lower limb

8. Single leg squat for balance training and strengthening

9. Closed chain core strengthening exercises

10. Agility drills for skill-specific training to improve functional activities

11. Warm up with 10–20 min of cycling or running

12. Single-leg balance on an unstable surface

13. Step-ups and lateral step-ups (up to 18–20 inches) with weight cuffs

14. Sports-specific cardiovascular training for aerobic fitness

15. Body weight squats

16. Deadlifts for hip mobility, front squats, and overhead squats for lower limb strengthening with upper limb stability.

Rehabilitative devices

1. BFR training can be used to increase muscle girth and cause hypertrophy.

Criteria for progression

1. No pain

2. Full ROM at the knee

3. Hop test >90% as compared to the uninvolved side

4. Quadriceps strength ≥90% of the uninvolved side

5. Able to run comfortably.

Goals

The goals of rehabilitation in this phase are as follows:

1. Maintain full ROM at the knee joint

2. Increase aerobic fitness

3. Achieve maximum muscle strength and endurance

4. Improve sports-specific explosive strength and power

5. Improve multidirectional balance and proprioception

6. Sports-specific and skill training

7. Achieve sports-specific fatigue to improve strength and endurance

8. Maintain full ROM at the knee joint

9. Increase aerobic fitness

10. Achieve maximum muscle strength and endurance

11. Improve sports-specific explosive strength and power

12. Improve multidirectional balance and proprioception

13. Sports-specific and skill training

14. Achieve sports-specific fatigue to improve strength and endurance

15. Sports psychology and nutritional counseling for multidisciplinary approach

16. Sports-specific strengthening of entire body.

Exercises

The following therapeutic exercises are recommended in this phase:

1. Warm up with 10–20 min of cycling or running

2. Single-leg balance on an unstable surface

3. Plyometric training for performance enhancement

4. Step-ups and lateral step-ups (up to 18–20 inches). Progress with weights and stepping exercises

5. Sports-specific cardiovascular training for maintaining optimal oxygen uptake

6. Reduce ground contact time and improve force production required for particular sports

7. Box jumps with a progressive increase in box heights, bounding, sprinting, hopping, and jumping with a soft landing

8. Agility drills for skill-specific training to enhance functional activities and increase lower limb endurance

9. Sports-specific strengthening.

It is important to note that rehabilitation may vary depending on the surgeon’s advice, the graft used for reconstruction, prehabilitation status, and patient compliance. All these factors should be considered while designing a tailored protocol for an individual. The overall rehabilitation outcome is gaining functional independence without any deficits in the knee joint. A collaborative approach is necessary to bridge the gap between different disciplines of the health profession.

In order to ensure the patients long term knee health and functional recovery, a properly planned rehabilitation program after ACL reconstruction is essential. The emphasis should be on a collaborative approach wherein the arthroscopic surgeon and the physiotherapist can showcase teamwork to ensure holistic care.

References

- 1.Kataoka K, Hoshino Y, Nukuto K. Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: Recent evolution and technical improvement. J Jt Surg Res 2023;1:97-102. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 2.Sood M, Kulshrestha V, Kumar S, Kumar P, Amaravati RS, Singh S. Trends and beliefs in ACL reconstruction surgery: Indian perspectives. J Clin Orthop Trauma 2023;39:102148. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 3.Cunha J, Solomon DJ. ACL prehabilitation improves postoperative strength and motion and return to sport in athletes. Arthrosc Sports Med Rehabil 2022;4:e65-9. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 4.Aspetar Sports Medicine Journal-Pre-Operative Preparation for ACL Reconstruction; 2023. Available from: https://journal.aspetar.com/en/archive/volume-12-targeted-topic-rehabilitation-after-acl-injury/pre-operative-preparation-for-acl-reconstruction [Last accessed date on 01 Jan 2025. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 5.Evans S, Shaginaw J, Bartolozzi A. Acl reconstruction-it’sall about timing. Int J Sports Phys Ther 2014;9:268-73. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 6.Waldron K, Brown M, Calderon A, Feldman M. Anterior cruciate ligament rehabilitation and return to sport: How fast is too fast? Arthrosc Sport Med Rehabil 2022;4:e175-9. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 7.De Mille P, Osmak J. Performance: Bridging the gap after ACL surgery. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med 2017;10:297-306. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 8.Palazzolo A, Rosso F, Bonasia DE, Saccia F, Rossi R. Uncommon complications after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Joints 2018;6:188-203. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 9.Buckthorpe M, Pirotti E, Villa FD. Benefits and use of aquatic therapy during rehabilitation after ACL reconstruction-a clinical commentary. Int J Sports Phys Ther 2019;14:978-93. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 10.Velázquez-Saornil J, Ruíz-Ruíz B, Rodríguez-Sanz D, Romero-Morales C, López-López D, Calvo-Lobo C. Efficacy of quadriceps vastus medialis dry needling in a rehabilitation protocol after surgical reconstruction of complete anterior cruciate ligament rupture. Medicine (Baltimore) 2017;96:e6726. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 11.Murray D, Clarkson C. Effects of moving cupping therapy on hip and knee range of movement and knee flexion power: A preliminary investigation. J Man Manip Ther 2019;27:287-94. [Google Scholar | PubMed]