Following our surgical protocol ensures predictable and satisfactory functional outcomes in complex talus fractures.

Dr. Ashish Agrawal, Department of Orthopaedics, R. D. Gardi Medical College, Ujjain 456006, Madhya Pradesh, India. E-mail: drfriendlyashish@gmail.com

Introduction: Talus fractures are troublesome injuries. It is very difficult to achieve good functional and radiological outcome in Hawkins type 3 comminuted fracture neck of talus.

Case Series: In our study, 7 cases of Hawkins type 3 comminuted fracture neck of talus were operated in R.D. Gardi Medical College, Ujjain between August 2020 to August 2023 with the sequence of early closed reduction of dislocation and application of external fixator (SPAN) on the day of admission, followed by 3 dimensional computed tomography – scanning (SCAN) and then, definitive surgery through open reduction of fracture (through dual incision approach) and internal fixation with cannulated cancellous screws (FIX) along with Primary bone grafting.

Results: With the surgical management protocol followed by us, the union was achieved in all 7 cases. Hawkins sign was seen in all 7 cases by 10 weeks post-operatively. There was no incidence of complications, such as wound dehiscence and infections post-operatively. The present study had a minimum follow-up of 6 months.

Conclusion: Our Surgical management protocol led to excellent functional and radiological outcomes in all cases. Patients were able to return to their pre-injury functional activities along with full-weight-bearing walking without support within 6 months of surgery.

Keywords: Hawkins classification, comminuted talus fracture, primary bone grafting.

Fractures of the talus are difficult injuries. Talus fractures are renowned for the high incidence of unsatisfactory results, due to the comparatively frequent incidence of serious complications such as osteonecrosis. Since the early descriptions by Anderson and others of the “aviator’s astragalus” fractures of the talus have earned a reputation as a problematic fracture [1]. Fractures of the talus are generally thought to be relatively uncommon. However, the talus is the second most commonly fractured tarsal bone. Most serious fractures of the talus are high-energy injuries. Fractures of the talar neck are commonly the result of a hyper dorsiflexion-type injury [1]. The most commonly used classification for talar neck fractures is that described by Hawkins [2] with the modifications suggested by Canale and Kelly [3], which relies mainly on displacement and dislocation, and therefore, suspected damage to the blood supply of the talus depending on its pattern of fracture displacement [2]. A Hawkins type I fracture is an undisplaced fracture, without any associated subluxation or dislocation component to it. A Hawkins type II fracture is a displaced vertical talar neck fracture with subluxation or dislocation of the subtalar/talocalcaneal joint. A Hawkins type III fracture is a displaced fracture spanning through the talar neck with dislocation at both the talocalcaneal and tibiotalar joints. The degree or the amount of displacement and dislocation is thought to be the primary assessing criteria of the interruption of its vascular status and therefore, the risk for the development of osteonecrosis as one of its dreaded complications. A type IV fracture is associated with a dislocation of the tibiotalar and subtalar joint, also with an additional dislocation or subluxation of the head of the talus at the talonavicular joint. A Hawkins Type III fracture involves a dislocation at the ankle as well as at the subtalar joint. In this case, osteonecrosis is the rule rather than the exception with rates of nearly 100% [3]. Emergent reduction of the dislocated talus is one of the key principles in the management of type 3 fractures of the talar neck, critical to maintain the vascularity of the talar body and to reduce tension on the skin, soft tissues, and associated neurovascular structures around the ankle. The Talus bone has a complex anatomy and a unique blood supply. 60% of its surface is covered by articular cartilage and it has 7 articular surfaces. The inferior articular facets with calcaneus form the subtalar joint. The anteromedial surface and central trochlear surface, with the lateral process form the talar portion of the ankle joint. Talus does not have any muscular attachments to it [4]. Talar neck fractures are almost always due to high-energy trauma because the thick subchondral bone prevents it from getting fractured in a trivial trauma [5]. Talar neck fractures represent almost 50% of all talus fractures [6-9]. Because of the early recognition and extensive literature on this type of fracture, there are a number of radiographic views described to visualize the neck. Computed tomography (CT) scan is more effective at giving the surgeon a complete picture of the injury as well as information on the surrounding structures [10]. Although there have been volumes written on the classification schemes and complications inherent with these injuries, recent literature shows that early restoration of anatomy with rigid fixation offers the surgeon the best chance of a good result [11,12]. The widely preferred approach for surgical treatment of talar neck fractures is a dual anterior incision technique [11, 13-16].

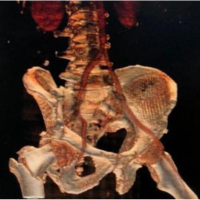

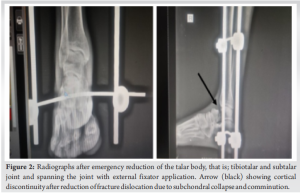

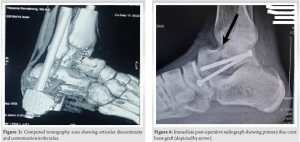

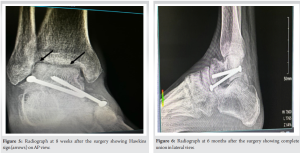

The study was conducted in the Department of Orthopaedics of R.D. Gardi Medical College, Ujjain, Madhya Pradesh from August 2020 to August 2023. In this study, 7 cases of Hawkins type 3 comminuted fracture neck of talus were admitted and treated by our protocol. Post-operative functional and radiological outcome was assessed in all cases. This study is an interventional case series. Inclusion criteria were fresh (<24 h of injury) Hawkins Type 3 fracture Neck of the talus, age >18 years to <60 years, and no past history of any ankle trauma. Exclusion criteria were late presenting patients (more than 24 h after injury), patients with neurovascular injury, patients with pre-existing deformity of the ankle joint, patients with compound injury to the ankle, and patients lost to a minimum of 6-months follow-up. All the patients presenting to the emergency department were initially assessed based on ankle X-rays both anteroposterior (AP) and lateral views and were hemodynamically stabilized. The patients were then admitted and a pre-operative workup was done. Patients were taken to the operation theatre within 6 h of presentation with the aim to reduce the dislocated talus body. After administration of appropriate anesthesia, Denham’s pin was inserted in the calcaneum. With the help of calcaneum traction and gentle direct pressure over the dislocated talus, the talar body was relocated into its normal position and this position was maintained with the help of a uniplanar bilateral external fixator. After the application of an external fixator, the patient’s injury was further evaluated with the help of a 3D CT scan. This enabled us to exactly evaluate the radiological characteristics of the fracture and thereby helped us to plan the definitive surgery in a better way. The emergency application of an external fixator maintained the reduction of the dislocated talus and the fracture till the swelling around the ankle reduced significantly permitting for definitive surgery. This protocol allowed us to negate possible post-operative complications, such as wound dehiscence and surgical site infection after definitive fixation of the fracture which are well-known complications when open reduction and/or definitive fixation are done in the presence of gross ankle swelling during the early days of trauma. After a waiting period of usually 7–10 days, as the swelling around the ankle subsided and the skin condition improved, definitive fixation was done. Talus was approached through dual incision, that is, anteromedial and anterolateral. The medial approach begins on the anterior border of the medial malleolus and bisects the space between the tibialis anterior and posterior tendons. The incision is curved proximally along the axis of the tibia to allow visualization of the tibiotalar joint. The anterolateral incision follows the extensor digitorum bundle from the tibiotalar joint to the lateral border of the navicular and lateral cuneiform bones. The extensor retinaculum is cut in a “Z” fashion to allow subsequent closure. With the extensor tendons laterally displaced, direct visualization of the lateral dome of the talar head, the shoulder of the neck, and the body and the neck are possible [11, 13-16]. After obtaining the maximum possible trial reduction, a cortico cancellous graft was harvested from the ipsilateral iliac crest. The bone graft was used to fill up all the fracture gaps that remained during the trial reduction as well as to hasten the healing process (by creeping substitution). After achieving the bony continuity, 2 cannulated cancellous screws of 4 mm were used to fix the fracture. Post-operatively the patient’s leg was put on a Bohler Braun splint in a below-knee slab. Patients were encouraged to do active toe movements from the day of surgery. Gradually the patients were encouraged to perform static and dynamic knee exercises and straight leg raising exercises as per the pain tolerance. Suture removal was done at 15–20 days post-operative depending on surgical wound healing. Patients were allowed non-weight-bearing walking with the help of walker support. After 6 weeks the slab was removed and active ankle movements were allowed. Post-operative X-rays were done at 8–10 weeks’ time to look for the presence of Hawkins sign. Once the Hawkins sign was seen on X-ray, patients were allowed to walk with partial weight bearing progressing gradually to full weight bearing over a period of 1 month with the help of walker support. Gradually patients were encouraged to shift from walker support to stick support and eventually walk without support over the next 3 months. At 6 months follow-up radiographs showed complete union, with no signs of subchondral collapse. Patients were able to walk full weight bearing without any support and carry out their daily routine activities (return to pre-injury functional status) at 6 months follow-up (Fig. 1, 2, 3, 4).

In the present study, the mean age of the cases was 47 years (Ranging from 18 to 60 years).

Out of 7 cases, 5 were males and 2 were females.

All 7 cases were presented to us within 24 h of injury.

Closed reduction of talar dome was done in all the cases within 6 h of presentation under appropriate anesthesia and an external fixator was applied to maintain the reduction in place till the time of definitive fixation. Swelling subsided in all the cases within 7–10 days of the application of an external fixator. A 3D CT scan was done in all 7 cases after the application of an external fixator. CT scan helped us to assess the comminution and fracture pattern in more detail as compared to routine X-rays. A dual incision approach was used in all the cases. 2 CC screws of 4 mm size were used in definitive fixation along with primary iliac crest bone grafting in all 7 cases. Definitive surgery was done under tourniquet control in all the cases. The average definitive surgery time was 60 min. Posterior below-knee slab support was given in the post-operative period. Suture removal was done 15–20 days post-operative in all the cases. Post-operative X-rays were done on the 2nd day, at 8–10 weeks and at 6 months. Hawkins sign was seen in all the 7 cases ranging from 8 to 10 weeks post-operatively, 5 of them had it at the 8th week and 2 at the 10th week. Partial weight bearing was started after visualization of Hawkins sign, that is; 5 of them were allowed at the 8th week and 2 at the 10th week post-operatively. Union was seen in all the cases at 6 months post-operatively. Out of the 7 cases, none of our patients had post-operative infection and wound dehiscence (Fig. 5, 6, 7).

Talus fractures are difficult injuries to treat, especially Hawkins type 3 neck fractures as they are prone to AVN and non-union along with wound-related complications, such as surgical site infection and wound dehiscence. Azeez et al. concluded that early open reduction and internal fixation of displaced fracture neck of talus to reestablish and maintain alignment has a major role in minimizing the complication rate, however; the post-traumatic sequel and complications may be inevitable [17]. In our study, patients presenting to us in the emergency department with a history of trauma <24 h were initially managed by hemodynamic stabilization and closed reduction of the talar dislocation under appropriate anesthesia within 6 h of the presentation. Closed reduction was achieved in all our cases with the help of gentle and sustained traction along with control of varus and valgus, manipulation by plantar flexion, and direct pressure on the talar body. According to Rockwood et al., excessive or prolonged direct pressure can increase the risk of overlying skin necrosis [18]. It is generally believed that closed reduction of this type of fracture dislocation, that is; reduction of the talar body back into the ankle mortise is difficult. It is believed that direct pressure increases the soft tissue tension around the ankle including the flexor tendons, posterior tibial tendon, and even the deltoid ligament thus making closed reduction more difficult as the tissues are overly tensioned. In our study, the key was achieving a closed reduction in all the cases without the use of overzealous force and the application of a uniplanar bilateral type of external fixator to maintain the talar body into the ankle mortise. Early closed reduction and application of an external fixator helped us in avoiding possible complications of skin (pressure) necrosis, wound dehiscence and infection, and also led to a faster decrease in swelling thereby enabling definitive fixation at an early date. Moger et al. concluded that delay in diagnosing these injuries accelerates vascular compromise, delays timely intervention, and ultimately leads to increased morbidity [19]. In our study, we strictly followed the protocol to reduce the talar body within 6 h of presentation and that too by the closed method, which eventually led to decreased morbidity associated with the trauma. Lengkong et al. concluded that open reduction and internal fixation with iliac crest cancellous bone graft is a reliable method for neglected non-union type III Hawkins fracture of neck talus with great functional outcomes after 14 months of follow-up [20]. In our study, we have done primary iliac crest bone grafting in all the cases. At the time of definitive surgery, accurate visualization of articular reduction was done from both medial and lateral sides. It was noted that, invariably, there was partial loss of articular congruity due to the subchondral gap despite the best possible efforts of achieving total articular continuity. This was because of the severity of the injury, causing subchondral cancellous bone impaction and comminution. To overcome this hurdle, we took a cortico cancellous graft from the iliac crest and filled the fracture gap with it (primary bone grafting). Leaving the fracture gap at the time of definitive fixation would have made the fracture susceptible to non-union as well as collapse. Furthermore, the cancellous nature of the graft promotes bone union and improves the vascularity around the fracture site by creeping substitution. Tehranzadeh et al. concluded that the Hawkins sign on X-ray does not always have to be complete to rule out avascular necrosis (AVN). Fractures of the talus can lead to AVN because of the disruption of end arteries within the body of the talus. Early recognition of the partial/total Hawkins sign should lead to magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) evaluation that can more readily define the involvement of the talar body and assist the treating physician in recommending when the patient can bear weight [21]. Hawkins type 3 fractures of the talus are prone to osteonecrosis [18]. We found in our study that after a period of 8–10 weeks post-operatively Hawkins sign was seen on X-ray in all the cases. The presence of the Hawkins sign, (that is, absence of osteonecrosis) ensured that our patients were allowed to walk partial weight bearing without the fear of collapse at a later stage. Absolute confirmation of the presence or absence of osteonecrosis requires MRI scanning which however is not possible in post-operative cases with an implant in situ and hence was not done in our patients.

Limitations

Short sample size and short follow-up period. Long-duration and large sample size studies are needed to obtain a detailed comprehensive analysis.

Hawkins type 3 comminuted fracture neck of talus treated with staged procedure consisting of initial closed reduction and External Fixator application, followed by a waiting period for swelling subsidence along with CT scan imaging followed by open reduction and fixation with Primary bone grafting yielded good results.

- A staged approach for Hawkins type 3 fractures is a viable option to treat these fractures effectively and avoids complications associated with early open reduction and internal fixation.

- Primary bone grafting ensures bone union, prevents AVN, and subsequent collapse.

References

- 1.Anderson HG. The Medical and Surgical Aspects of Aviation. London: Oxford University Press; 1919. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 2.Hawkins LG. Fractures of the neck of the talus. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1970;52:991-1002. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 3.Canale ST, Kelly FB Jr. Fractures of the neck of the talus. Long-term evaluation of seventy-one cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1978;60:143-56. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 4.Adelaar RS. The treatment of complex fractures of the talus. Orthop Clin North Am 1989;20:691-707. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 5.Heckman JD. Fractures of the talus. In: Rockwood and Green’s Fractures in Adults. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; 2001. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 6.Vallier HA, Nork SE, Benirschke SK, Sangeorzan BJ. Surgical treatment of talar body fractures. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2003;85:1716-24. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 7.Elgafy H, Ebraheim NA, Tile M, Stephen D, Kase J. Fractures of the talus: Experience of two level 1 trauma centers. Foot Ankle Int 2000;21:1023-9. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 8.Adelaar RS. Complex fractures of the talus. In: Adelaar RS, editor. Complex Foot and Ankle Trauma. Ch. 7. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott-Raven; 1999. p. 65-94. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 9.Higgins TF, Baumgaertner MR. Diagnosis and treatment of fractures of the talus: A comprehensive review of the literature. Foot Ankle Int 1999;20:595-605. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 10.Chan G, Sanders DW, Yuan X, Jenkinson RJ, Willits K. Clinical accuracy of imaging techniques for talar neck malunion. J Orthop Trauma 2008;22:415-8. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 11.Vallier HA, Nork SE, Barei DP, Benirschke SK, Sangeorzan BJ. Talar neck fractures: Results and outcomes. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2004;86:1616-24. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 12.Lindvall E, Haidukewych G, DiPasquale T, Herscovici D Jr., Sanders R. Open reduction and stable fixation of isolated, displaced talar neck and body fractures. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2004;86:2229-34. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 13.Vallier HA, Reichard SG, Boyd AJ, Moore TA. A new look at the Hawkins classification for talar neck fractures: Which features of injury and treatment are predictive of osteonecrosis? J Bone Joint Surg Am 2014;96:192-7. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 14.Sanders DW, Busam M, Hattwick E, Edwards JR, McAndrew MP, Johnson KD. Functional outcomes following displaced talar neck fractures. J Orthop Trauma 2004;18:265-70. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 15.Xue Y, Zhang H, Pei F, Tu C, Song Y, Fang Y, et al. Treatment of displaced talar neck fractures using delayed procedures of plate fixation through dual approaches. Int Orthop 2014;38:149-54. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 16.Vallier HA. Fractures of the talus: State of the Art. J Orthop Trauma 2015;29:385-92. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 17.Azeez A, Srinivasan N, Reddy VN. Management of fracture neck of talus and clinical evaluation. Int J OrthopSci 2018;4:16-21. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 18.Bucholz RW, Heckman JD, Court-Brown CM. Rockwood and Green’s Fractures in Adults. 7th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2001 2002. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 19.Moger NM, Pragadeeshwaran J, Verma A, Aditya KY, Aditya KS, Meena PK. Outcome of neglected talus neck fracture and it’s management: A case report. J Orthop Case Rep 2021;11:41-4. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 20.Lengkong AC, Kennedy D, Senduk RA, Usman MA. Management of 3 month old neglected talus neck fracture: A case report and review of literature. Trauma Case Rep 2023;43:100764. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 21.Tehranzadeh J, Stuffman E, Ross SD. Partial Hawkins sign in fractures of the talus: A report of three cases. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2003;181:1559-63. [Google Scholar | PubMed]