Promptly diagnosing pectoralis major tendon injuries to allow early repair and improved functional and cosmetic outcomes

Dr. Maulik Kothari, Department of Orthopaedics, Seth GS Medical College and KEM Hospital, Mumbai, Maharashtra, India. E-mail: mkothari8@gmail.com

Introduction: Pectoralis major tendon (PMT) tears are increasingly common, particularly among young, athletic individuals.

Case Report: This case report discusses the management of a chronic PMT tear in a 24-year-old professional wrestler who sustained an injury during a wrestling match. Initially treated conservatively with immobilization and physiotherapy, the patient presented 1 year later with unsatisfactory functional outcomes. Clinical examination and imaging confirmed the retracted tendon, leading to a decision for surgical repair. An open repair of the PMT was performed using a standard clavipectoral approach with suture anchors to reattach the tendon to its anatomical insertion on the humerus. Post-operative rehabilitation focused on progressive range of motion and strength training, enabling the patient to return to pre-injury levels of athletic performance after 8 months.

Conclusion: The results highlight the importance of early diagnosis, prompt surgical intervention, and a structured rehabilitation plan in achieving optimal functional and cosmetic outcomes in young athletes with chronic PMT tears.

Keywords: Pectoralis major tendon, suture anchor, sports, wrestling.

The pectoralis major is a key adductor and internal rotator of the shoulder. The first reported case of a pectoralis major tendon (PMT) tear was attributed to heavy lifting, such as meat off hooks, rather than activities, such as the bench press [1]. The incidence of PMT tears is on the rise due to greater participation in lifting activities, yet the limited literature on its operative management provides insufficient information on treatment algorithms [2].

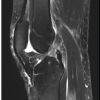

We present the case of a 24-year-old male professional wrestler who presented to us 1 year after an injury. During a wrestling match, the patient attempted a throwing move, resulting in a sudden pop and tearing sensation. He immediately discontinued the bout, and medical staff advised shoulder immobilization and ice compression. Plain X-rays revealed no bony injuries. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans showed an acute tear of the PMT (Fig. 1). The patient was initially managed conservatively with shoulder immobilization followed by gradual physiotherapy to regain strength and range of motion. After 1 year of physiotherapy, he returned to us with unsatisfactory results.

On examination, the contour of the anterior axillary fold was lost, and the nipple on the affected side was lower, as evident in the prayer position (Fig. 2). The shoulder girdles were asymmetrical, and there was noticeable muscle atrophy around the affected shoulder. A palpable mass was found at the site of the retracted tendon, with associated tenderness. The patient could not achieve full adduction actively, although passive movement was possible. Strength in adducted internal rotation was decreased. Plain radiographs showed no bony injuries, and a repeat MRI scan revealed a tear in the PMT, with increased retraction compared to the initial scan. Given the patient’s professional requirements, a decision was made to perform an open repair of the PMT with the goal of achieving functional range and strength, enabling him to return to competitive wrestling. The patient was positioned in a beach chair under general anesthesia. After sterile preparation, relevant bony landmarks were marked. A standard clavipectoral approach was used (Fig. 3). The cephalic vein was isolated, and the deltopectoral interval was dissected, with varying amounts of scar tissue encountered. Known bony landmarks (coracoid, acromion, and clavicle) aided in the dissection. The plane between the remaining PMT and the deltoid muscle was developed. The clavicular head of the pectoralis major muscle was found to be intact (Fig. 4), while the sternal head was retracted medially along the chest wall (Fig. 5). After clearing adhesions, the sternal head was mobilized laterally (Fig. 6). The tear was identified approximately 2 mm lateral to the musculotendinous junction. The tendon was debrided and the margins were freshened. The insertion on the humeral surface was identified (Fig. 7). The biceps tendon and sheath were retracted medially to prevent impingement. Two 5 mm double-loaded titanium suture anchors were placed at the humeral footprint, and sutures were taken through the tendon remnant and musculotendinous junction, extending into the muscle substance. The arm was positioned in adduction and internal rotation, and the final tightening of the suture anchors was done in a tension-free manner. The repair’s strength was checked across the shoulder’s range of motion and was found to be satisfactory. The clavipectoral approach was closed in layers (Fig. 8).

Post-operatively, the patient was given a sling for comfort. Early physical therapy was initiated, focusing on passive and assisted active range of motion. Flexion up to 90°, abduction up to 45°, and external rotation up to 30° were permitted initially, with gradual increases over time. Resistance training was started 6–8 weeks later, and competitive sports training was permitted after 6 months. The disabilities of arm, shoulder, and hand score was used to assess the patient’s functional outcome. Initially, the score was 86 at presentation, but it improved to 69 after 2 months and to 28 after 6 months of intensive physical therapy. The patient resumed pre-injury levels of athletic training after 8 months, achieving satisfactory cosmetic and functional results (Fig. 9).

Once considered a rare injury, pectoralis major tears are now increasingly common, likely due to greater awareness, improved healthcare access, and advanced imaging techniques [3]. These injuries typically affect young males involved in athletic activities, with anabolic steroid use further increasing the risk of muscle tears [4]. The pectoralis major originates from the lateral sternum and inferior clavicle, inserting 4 cm distal to the greater tuberosity of the humerus, on the lateral lip of the bicipital groove. Its footprint on the humerus measures 70 mm by 1.4 mm. There is a well-known musculotendinous twist before insertion, with the sternal head inserting deeper and more proximally than the clavicular head on the humerus [5]. As the muscle is responsible for shoulder adduction and internal rotation, most tears occur when the shoulder is abducted and externally rotated, as seen during bench pressing [6]. PMT injuries often occur during exercise, particularly during the eccentric phase of bench pressing, and are most common in young athletes. They typically occur at the bone-tendon junction, although intrasubstance tears are also seen [7]. Patients usually experience a pop followed by a sharp tearing sensation and an inability to perform adduction and internal rotation of the affected shoulder. Acute tears often involve bruising, and the retracted tendon is often palpable and tender. If associated with an avulsion fracture at the humeral insertion, localized tenderness over the humerus may also be present. In chronic tears, disuse atrophy of the shoulder can develop, and the chest’s contour is distorted, as seen with a drooped nipple. Our patient followed this pattern, with the injury occurring during a wrestling match. Despite initial acute care, the root cause was not addressed, leading to continued loss of strength and function [8]. Diagnosis is typically confirmed through examination, but MRI remains the gold standard for confirming the tear, as it provides valuable information regarding tear morphology, location, retraction, and muscle quality in chronic cases. The initial MRI showed a tear at the musculotendinous junction, and retraction was more pronounced on the follow-up scan. The Tietjen classification is commonly used to categorize PMT tears [9]. Our patient was classified as type IIIC (tear at the musculotendinous junction). Treatment options include both surgical and non-surgical approaches. In older individuals with less functional demand, conservative management may be appropriate. However, for young, active individuals, particularly athletes, surgical repair is preferred and yields excellent functional and cosmetic results [10,11]. Various surgical techniques have been described, including suture anchors, bone tunnels, transosseous sutures, cortical buttons, and cortical screws, all aimed at reattaching the muscle to its anatomical insertion [12]. We prefer suture anchors for stable anatomic fixation in young athletes. Chronic injuries, defined as those occurring more than 6 weeks post-injury [13], are associated with significant retraction and scarring. Surgical results are generally better with acute injuries [14]. For chronic injuries with significant retraction, autografts or allografts may be necessary [12]. The deltopectoral interval remains the standard approach. The cephalic vein must be respected to prevent post-operative limb edema. In chronic tears, scar tissue formation and retraction of the muscle belly occur, and careful dissection is required to mobilize the tendon. An intact clavicular head can aid in identifying the retracted sternal head and locating the humeral insertion. The conjoint tendon must be handled gently to avoid injury to the musculotendinous nerve, and the biceps tendon must be retracted medially to avoid impingement. Final tightening should be performed with the shoulder in adduction and internal rotation, ensuring stability throughout the range of motion. Physical therapy and rehabilitation are essential for achieving optimal functional outcomes and returning athletes to competitive sports [15].

This case highlights the successful surgical management of a chronic pectoralis major tear in a young athlete, emphasizing the importance of physical therapy in achieving cosmetic and functional goals and ensuring a return to optimal performance. Early diagnosis and prompt surgical intervention are crucial. Mobilizing the retracted tendon and removing adhesions are key steps in achieving the best results in chronic tears. Stable fixation using suture anchors, followed by early physical therapy to improve range of motion and strength, are recommended for athletes returning to competition.

Use clinical acumen and imaging modalities to diagnose PMT injuries early and achieve a stable anatomical fixation to allow early return to sports.

References

- 1.Provencher MT, Handfield K, Boniquit NT, Reiff SN, Sekiya JK, Romeo AA. Injuries to the pectoralis major muscle: Diagnosis and management. Am J Sports Med 2010;38:1693-705. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 2.Ziskoven C, Patzer T, Ritsch M, Krauspe R, Kircher J. Die zeitgemäße Therapie der kompletten Ruptur des M. pectoralis major [Current treatment options for complete ruptures of the pectoralis major tendon]. Sportverletz Sportschaden 2011;25:147-52. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 3.Bodendorfer BM, Wang DX, McCormick BP, Looney AM, Conroy CM, Fryar CM, Kotler JA, Ferris WJ, Postma WF, Chang ES. Treatment of Pectoralis Major Tendon Tears: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Repair Timing and Fixation Methods. Am J Sports Med. 2020 Nov;48(13):3376-3385. doi: 10.1177/0363546520904402. Epub 2020 Feb 28. [Google Scholar | PubMed | CrossRef]

- 4.Stefanou N, Karamanis N, Bompou E, Vasdeki D, Mellos T, Dailiana ZH. Pectoralis major rupture in body builders: A case series including anabolic steroid use. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2023;24:264. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 5.ElMaraghy AW, Devereaux MW. A systematic review and comprehensive classification of pectoralis major tears. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2012;21:412-22. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 6.Wolfe SW, Wickiewicz TL, Cavanaugh JT. Ruptures of the pectoralis major muscle. An anatomic and clinical analysis. Am J Sports Med 1992;20:587-93. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 7.Pavlik A, Csépai D, Berkes I. Surgical treatment of pectoralis major rupture in athletes. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 1998;6:129-33. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 8.Bak K, Cameron EA, Henderson IJ. Rupture of the pectoralis major: A meta-analysis of 112 cases. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2000;8:113-9. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 9.Tietjen R. Closed injuries of the pectoralis major muscle. J Trauma 1980;20:262-4. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 10.De Castro Pochini A, Andreoli CV, Belangero PS, Figueiredo EA, Terra BB, Cohen C, et al. Clinical considerations for the surgical treatment of pectoralis major muscle ruptures based on 60 cases: A prospective study and literature review. Am J Sports Med 2014;42:95-102. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 11.Aärimaa V, Rantanen J, Heikkilä J, Helttula I, Orava S. Rupture of the pectoralis major muscle. Am J Sports Med 2004;32:1256-62. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 12.Butt U, Mehta S, Funk L, Monga P. Pectoralis major ruptures: A review of current management. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2015;24:655-62. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 13.Flint JH, Wade AM, Giuliani J, Rue JP. Defining the terms acute and chronic in orthopaedic sports injuries: A systematic review. Am J Sports Med 2014;42:235-41. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 14.Long MK, Ward T, DiVella M, Enders T, Ruotolo C. Injuries of the pectoralis major: Diagnosis and management. Orthop Rev (Pavia) 2022;14:36984. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 15.Manske RC, Prohaska D. Pectoralis major tendon repair post-surgical rehabilitation. N Am J Sports Phys Ther 2007;2:22-33. [Google Scholar | PubMed]