Addressing psychological well-being, pain, and overall health is crucial in improving quality of life for patients with knee-related conditions, regardless of a specific osteoarthritis diagnosis.

Dr. Dimitrios Giotis, Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, General Hospital of Ioannina “G. Hatzikosta” 60 Stratigou Makrigianni Avenue, Ioannina 45445, Greece E-mail: dimitris.p.giotis@gmail.com

Introduction: Osteoarthritis (OA) is a prevalent disease that affects the quality of life (QoL) not only through pain and physical disability but also by influencing social and psychological aspects of life. This study aims to compare patients diagnosed with knee OA to those with knee pain and other comorbidities to evaluate the specific impact of OA on QoL.

Materials and Methods: A total of 150 patients presenting with knee pain or knee OA were assessed using standardized QoL instruments, including the World Health Organization QoL-BREF (WHOQOL-BREF), the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Arthritis Index (WOMAC), the Brief Illness Perception Questionnaire (Brief IPQ), and the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9).

Results: The influence of various factors, such as patient characteristics, demographics, medical history, medication use, OA diagnosis, and related symptoms, was analyzed using regression models. Significant correlations were observed between QoL and variables including knee injuries (WOMAC score: 54.662 vs. 38.657, P < 0.001), depression (PHQ-9: 9.894 vs. 6.608, P < 0.001), elevated BMI (WOMAC: F = 5.305, P = 0.023), and occasional crepitus (WOMAC score: 53.144 vs. 40.175, P = 0.003). No statistically significant differences were found between patients with OA and those with other diagnoses in any of the outcome measures.

Conclusions: The findings suggest that QoL is influenced more by general factors such as psychological well-being (depression), pain (knee injuries), and overall health (BMI) rather than the specific diagnosis of OA. This underscores the importance of addressing these broader health attributes to improve the QoL in patients with knee-related issues.

Keywords: Knee osteoarthritis, quality of life, knee pain, psychological aspects, health status.

Osteoarthritis (OA) is the most common musculoskeletal disorder worldwide, affecting approximately 30 million adults in the United States [1]. It is characterized by the degeneration of articular cartilage, osteophyte formation, and asymmetric joint space narrowing [2]. This degenerative disease primarily affects mostly the knee joint [2]. The impact of OA on patients’ quality of life (QoL) varies significantly among individuals and may not correlate directly with the severity of structural joint abnormalities. In addition, perceptions of QoL are dynamic and difficult to measure, as they are influenced by biopsychosocial factors and associated comorbidities that can further complicate the condition [3]. To address these complexities, various instruments and scales have been developed to quantify QoL based on psychological, social, and physical dimensions as defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) in forms of certain validated questionnaires [4]. Given the heterogeneous nature of OA as a clinical entity, it leads to varying degrees of morbidity and QoL impairment among patients [3]. Moreover, aging, an inevitable process, is associated with a higher prevalence of chronic diseases and disabilities in the elderly compared to younger age groups. These limitations are often linked to reductions in QoL [4]. The purpose of this study was to assess the impact of knee OA on patients` QoL and identify factors contributing to impaired QoL. To achieve this, psychological, social, and physical parameters were evaluated in patients diagnosed with knee OA and compared to individuals experiencing knee pain associated with other comorbidities.

Subjects

From January 2020 to December 2020, 150 patients participated in this cross-sectional study. One hundred and twenty-seven females and 23 males diagnosed with knee OA (according to Kellgren and Lawrence classification) or presenting with knee pain were included in the study. Patients under the age of 40 or over 75 years old, as well as those with a history of previous knee surgery or other osteometabolic, rheumatic or chronic, and degenerative diseases that could affect the QoL, were excluded from the study. Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the Institutional Review Board, and all participants were informed about data confidentiality and anonymity. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients, in accordance with the procedures outlined by our Institutional Review Board.

Procedure

The patients enrolled in the study were asked to complete questionnaires assessing physical, mental, and psychosocial parameters. These questionnaires included items related to knee pain and physical function, as well as demographic, socioeconomic, disease-related, and psychological variables. To evaluate the QoL and all requested parameters for each participant, the following instruments were used: the World Health Organization QoL-BREF (WHOQOL-BREF), the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Arthritis Index (WOMAC), the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9), and the Brief Illness Perception Questionnaire (Brief IPQ). The WHOQOL-BREF consists of 26 items, including two general questions that evaluate overall QoL and 24 questions assessing four domains: physical health, psychological health, social relationships, and the environment [5]. The WOMAC is a self-administered questionnaire with 24 items (five for pain, two for stiffness, and 17 for physical function) and is widely used for assessing knee OA [6]. The PHQ-9 is a validated tool for screening, diagnosing, monitoring, and measuring the severity of depression. The Brief IPQ assesses patients’ cognitive and emotional perceptions of their illness, including consequences, timeline, personal control, treatment control, identity, coherence, concern, emotional response, and causes [7,8]. All instruments were translated into Greek and validated for the Greek population [9,10]. In addition, various external parameters were considered for each participant, including gender, age, height, weight, body mass index (BMI), menopause status, knee injuries (right or left), diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, antidepressant treatment, contraceptive use and duration, duration of symptoms, pain, morning stiffness, radiological OA grading, crepitus, pain during motion, pain severity (0–10 scale), range of motion limitations, muscle atrophy, axonal disorders, edema, and deformities. Standing anteroposterior and lateral radiographs of both knees were obtained for each participant, and the severity of OA was graded by two independent radiologists using the Kellgren and Lawrence grading system. In parallel, knee function was evaluated in terms of pain, range of motion, edema, muscle strength, instability, and crepitus by two independent orthopedic surgeons.

Statistics

Descriptive statistics were presented as mean and standard deviation (SD). Outcome measures were evaluated for significance using T-tests or analysis of variance (ANOVA) after addressing outliers and data skewness. A multiple regression model was employed to assess the effects of all variables on the dimensions of the PHQ-9, Brief IPQ, and WOMAC scales. Main effects and second-order interactions were analyzed. The Bonferroni criterion was applied to adjust for multiple comparisons, determining the observed significance levels for within- and between-group differences. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05. Data analysis was conducted using SPSS v.26 (Chicago, IL).

The mean age of the examined sample was 61.80 ± 8.07 years, while the BMI was 29.51 ± 5.41 kg/m2. Patients’ demographic data are provided in Table 1, which also shows that the average use of contraceptives was 8.23 ± 19.54 months. In Table 2, patients’ characteristics related to pain and function are outlined. The average duration of symptoms was 31.62 ± 29.01 months.

Regression analyses results

Univariate analysis for factors affecting the WOMAC scale indicated that higher scores were recorded in patients with a higher BMI and in those with knee injuries (right or left). Significantly higher values were also observed in patients with crepitus and limitations in range of motion (Table 3). P-values for these parameters are presented in Table 4 alongside their respective 95% confidence intervals. The mean pain score for patients with injuries was 54.662, compared to 38.657 for patients without injuries (P < 0.001). The mean WOMAC total score was 53.144 in patients with crepitus versus 40.175 in those without crepitus (P = 0.003). Similarly, patients with limitations in range of motion had significantly higher WOMAC scores compared to those without limitations (P = 0.036). In addition, higher BMI was associated with higher WOMAC scores (P = 0.023). The adjusted R² of the model accounted for approximately 37% of the total variability, suggesting that these four factors (knee injuries, crepitus, limitations in range of motion, and BMI) explain a substantial portion of the variance in the WOMAC scale.

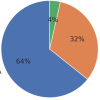

Regarding the Brief IPQ Scale, the analysis revealed that patients with crepitus presented higher scale values. Among all examined factors, crepitus was the only one statistically significant. Patients with crepitus had a mean score of 46.934 compared to 35.397 in those without crepitus, indicating that the worst perception for the examined sample was associated with patients experiencing crepitus. As far as “Physical Health” is concerned, the analysis of factors showed that lower values for the scale were observed in patients with higher BMI, knee injuries (right or left), crepitus, and edema. Similar to the Brief IPQ scale, crepitus had a significant impact, along with knee injuries, edema, and BMI. The adjusted R² of the four-factor model was approximately 33%, demonstrating its utility in assessing factors influencing patients’ physical health. In terms of “Psychological Health,” lower scores were observed in patients with knee injuries, walking instability, and those receiving antidepressant therapy, all showing statistical significance. This three-factor model accounted for nearly 29% of the total variability. Statistical differences for “crepitus” and “knee injuries” are illustrated in Fig. 1.

Concerning “Social relationships and Social Health,” lower scores were noted in patients with edema, knee injuries, and antidepressant therapy, which indicated that these three factors can play a major role in patients’ social relationships. These factors appeared to have similar effects on patients’ social health, as no significant differences were observed between them. The adjusted R² for this model was 23%, indicating that these factors play a moderate role in affecting patients’ social aspects. Analysis of environmental factors showed that lower scores were only associated with patients undergoing antidepressant therapy. This suggests that environmental dimensions are not significantly impacted by the examined factors, with antidepressant therapy being the sole contributor. The overall effect was minimal, with less than 10% variability explained, indicating the influence of unmeasured factors on this domain. Finally, analysis of the PHQ-9 questionnaire revealed higher scores in patients receiving antidepressant therapy. While no other factors were statistically significant, the impact of antidepressants on PHQ-9 was notable. The adjusted R² for this model exceeded 17%, indicating that antidepressants had a comparatively larger effect on this scale than on environmental factors.”

The results of this cross-sectional study demonstrated that QoL aspects are influenced by factors not exclusively associated with OA. This finding suggests that QoL depends not only on the specific diagnosis but also on psychological conditions (depression), pain (knee injuries), and overall health status (BMI). The study sample consisted of individuals, primarily women, aged 40 and 75 years, with knee pain and comorbidities or knee pain with diagnosed OA. Comorbidities included diabetes mellitus, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and depression among others [11]. Since the risk of OA increases with age, nearly all individuals entering the ninth decade of life show radiographic signs of knee joint degeneration. Thus, patients older than 75 years were excluded to focus on a more specific population [12]. Moreover, the predominance of females in our study aligns with findings by Segal et al., who reported that women are more predisposed to knee OA than men [13]. Similarly, Sale et al. confirmed that females are at higher risk for OA [14]. Regarding the comorbidities, diabetes mellitus (DM), high blood pressure, or dyslipidemia are components of metabolic syndrome and may together or independently participate in OA pathophysiology as presented by several epidemiological studies which report that metabolic syndrome and OA have been found to be associated [15,16]. In parallel, concerning the depression, in a population-based survey of individuals living in 17 countries, it was revealed that depression and anxiety disorders are significantly more common among individuals with self-reported arthritis [14]. Similarly, it has been reported that anxiety and depression can significantly impair QoL of patients by altering pain perception and functional capacity [17]. Health-related QoL (HRQoL) encompasses psychological, physical, and social dimensions linked to health conditions or therapies [18]. In our study, in assessment of QoL using the WOMAC instrument, higher scores were demonstrated in subjects with crepitus, knee injuries, higher BMI and limited range of motion which indicated that pain, heavy weight, crepitus, and reduced physical and joint function, impaired the QoL. In accordance with these results was the outcome of Brief IPQ system, where it was found that crepitus was related to diminished QoL. Crepitus, characterized by cracking or popping sounds around a joint, is a common clinical sign associated with prevalent OA. It is predictive of symptomatic OA progression and linked to the presence of osteophytes or cartilage damage, as supported by imaging studies [19]. The impact of knee pain and knee OA on HRQoL has been investigated in literature [20]. Pain is regarded as the predominant symptom in patients with symptomatic OA affecting different domains of QoL such as sleep interruption, psychological stress, reduced independence, poorer perceived health, and increased healthcare utilization [20]. Several studies underline that radiographic progression of knee OA is correlated with a shift from intermittent pain alone to severe pain [20,21]. In our sample, there were patients with knee pain that were found to have x-ray abnormalities consistent with radiographic knee OA. However, less than half of them had radiographic evident OA according to Kellgren and Lawrence, mainly stages I and II, while most of them were not diagnosed with this degenerative disease. It was also observed that BMI was related to patients’ knee pain and functional level of the joint. Obesity is regarded as a risk factor for knee OA as the excess body weight leads to deterioration of degenerative cartilage lesions by increasing the stress on the weight bearing joints, causing articular pain, muscle pain, and discomfort [16,22]. Beyond biomechanical effects, obesity may also have a systemic metabolic impact on OA progression. Specifically, leptin, a small polypeptide for regulation of food intake and energy expenditure at the hypothalamic level, has been reported to potentially provide the metabolic link between obesity and OA [23]. Plasma levels of leptin strongly correlate with fat mass as levels fall after weight loss. There have been also detected leptin receptors on human adult articular chondrocytes. Likewise, leptin might participate in the development of OA through changes in bony matrix [23]. Regardless the specific causes of obesity, there might be a considerable psychological relation to the QoL of obese individuals. Studies have reported that obese individuals might be negatively impacted by judgments and criticisms and these negative feelings might cause anxiety and depression [24]. To summarize, the present study demonstrates that patients with knee pain, regardless of OA diagnosis, report poorer HRQoL as assessed by both generic- and disease-specific instruments [25]. Obesity, crepitus, stiffness, and depression emerged as significant contributors to physical and mental QoL impairments, while OA itself was not the primary determinant of diminished HRQoL. However, our study has several limitations. The sample was predominantly female, and the severity of OA was confined to lower to moderate grades (Kellgren and Lawrence 0-III). Another weakness of our study was that it relied on self-evaluated knee pain and self-reported HRQoL from different and variant social groups. Finally, the study did not account for the duration of OA and its long-term effects on physical and mental health.

This study highlights that QoL in patients with knee pain, whether or not diagnosed with OA, is influenced more by factors such as pain, crepitus, obesity, and depression rather than the specific diagnosis of OA. Regardless of OA status, these elements significantly impact physical, psychological, and social well-being. A holistic treatment approach addressing both physical and mental health is crucial for improving patient outcomes. Future research should focus on targeted interventions to enhance overall QoL in individuals with knee-related conditions.

QoL in patients with knee-related conditions is influenced more by broader health factors such as psychological well-being, pain management, and overall health rather than the specific diagnosis of OA. Comprehensive care addressing these general attributes is essential to improving patient outcomes.

References

- 1.Johnson VL, Hunter DJ. The epidemiology of osteoarthritis. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2014;28:5-15. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 2.Lories RJ, Luyten FP. The bone-cartilage unit in osteoarthritis. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2011;7:43-9. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 3.Cihan E, Şahbaz Pirinççi C, Leblebicier MA. Effects of osteoarthritis grades on pain, function and quality of life. J Back Musculoskelet Rehabil 2024;37:793-9. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 4.The Whoqol Group. The world health organization quality of life assessment (WHOQOL): Development and general psychometric properties. Soc Sci Med 1998;46:1569-85. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 5.Skevington SM, Lotfy M, O’Connell KA, WHOQOL Group. The world health organization’s WHOQOL-BREF quality of life assessment: Psychometric properties and results of the international field trial. A report from the WHOQOL group. Qual Life Res 2004;13:299-310. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 6.McConnell S, Kolopack P, Davis AM. The western Ontario and MCmaster universities osteoarthritis index (WOMAC): A review of its utility and measurement properties. Arthritis Rheum 2001;45:453-61. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 7.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL. The PHQ-9: A new depression diagnostic and severity measure. Psychiatr Ann 2002;32:509-21. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 8.Broadbent E, Petrie KJ, Main J, Weinman J. The brief illness perception questionnaire. J Psychosom Res 2006;60:631-7. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 9.Ginieri-Coccossis M, Triantafillou E, Tomaras V, Soldatos C, Mavreas V. Psychometric properties of WHOQOL-BREF in clinical and health Greek populations: Incorporating new culture-relevant items. Psychiatriki 2012;23:130-42. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 10.Papathanasiou G, Stasi S, Oikonomou L, Roussou I, Papageorgiou E, Chronopoulos E, et al. Clinimetric properties of WOMAC index in Greek knee osteoarthritis patients: Comparisons with both self-reported and physical performance measures. Rheumatol Int 2015;35:115-23. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 11.Leite AA, Costa AJ, Lima BA, Padilha AV, De Albuquerque EC, Marques CD. Comorbidities in patients with osteoarthritis: Frequency and impact on pain and physical function. Rev Bras Reumatol 2011;51:118-23. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 12.Covinsky KE, Lindquist K, Dunlop DD, Gill TM, Yelin E. Effect of arthritis in middle age on older-age functioning. J Am Geriatr Soc 2008;56:23-8. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 13.Segal NA, Nilges JM, Oo WM. Sex differences in osteoarthritis prevalence, pain perception, physical function and therapeutics. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2024;32:1045-53. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 14.Sale JE, Gignac M, Hawker G. The relationship between disease symptoms, life events, coping and treatment, and depression among older adults with osteoarthritis. J Rheumatol 2008;35:335-42. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 15.Lee BJ, Yang S, Kwon S, Choi KH, Kim W. Association between metabolic syndrome and knee osteoarthritis: A cross-sectional nationwide survey study. J Rehabil Med 2019;51:464-70. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 16.Sampath SJ, Venkatesan V, Ghosh S, Kotikalapudi N. Obesity, metabolic syndrome, and osteoarthritis-an updated review. Curr Obes Rep 2023;12:308-31. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 17.Zheng S, Tu L, Cicuttini F, Zhu Z, Han W, Antony B, et al. Depression in patients with knee osteoarthritis: Risk factors and associations with joint symptoms. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2021;22:40. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 18.Revicki DA. Health-related quality of life in the evaluation of medical therapy for chronic illness. J Fam Pract 1989;29:377-80. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 19.Lo GH, Strayhorn MT, Driban JB, Price LL, Eaton CB, Mcalindon TE. Subjective crepitus as a risk factor for incident symptomatic knee osteoarthritis: Data from the osteoarthritis initiative. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2018;70:53-60. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 20.Muraki S, Akune T, Oka H, En-Yo Y, Yoshida M, Saika A, et al. Association of radiographic and symptomatic knee osteoarthritis with health-related quality of life in a population-based cohort study in Japan: The ROAD study. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2010;18:1227-34. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 21.Riddle DL, Stratford PW. Knee pain during daily tasks, knee osteoarthritis severity, and widespread pain. Phys Ther 2014;94:490-8. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 22.Thijssen E, Van Caam A, Van Der Kraan PM. Obesity and osteoarthritis, more than just wear and tear: Pivotal roles for inflamed adipose tissue and dyslipidaemia in obesity-induced osteoarthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2015;54:588-600. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 23.Yan M, Zhang J, Yang H, Sun Y. The role of leptin in osteoarthritis. Medicine (Baltimore) 2018;97:e0257. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 24.Steptoe A, Frank P. Obesity and psychological distress. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 2023;378:20220225. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 25.Tekaya AB, Bouzid S, Kharrat L, Rouached L, Galelou J, Bouden S, et al. Health-related quality of life and associated factors among patients with knee osteoarthritis. Curr Rheumatol Rev 2023;19:355-61. [Google Scholar | PubMed]