Focused assessment with sonography for trauma (FAST) is a quick and simple method for detecting intra-abdominal hemorrhage. However, in the context of pelvic fractures with retroperitoneal hemorrhage, it may yield false-positive results, potentially leading to non-therapeutic laparotomies.

Dr. Mantu Jain, Department of Orthopaedics, AIIMS, Bhubaneswar, Odisha, India. E-mail: montu_jn@yahoo.com

Introduction: Focused assessment with sonography for trauma (FAST) is an important adjunct for quickly detecting intra-abdominal hemorrhage. The study was aimed to identify the incidence of non-therapeutic laparotomies with positive FAST result and pelvic fracture.

Materials and Methods: A retrospective review of prospectively maintained data was conducted to identify cases of pelvic fracture with positive FAST results. Cases with non-therapeutic laparotomies were analyzed for the cause of false FAST positive result. The data were collected and analyzed for the mechanism of injury, associated injuries and injury severity.

Results: Out of 195 cases of pelvic fracture with positive FAST result, only 5 cases (2.5%) had non-therapeutic laparotomies. Most were operated without a computed tomography scan due to hemodynamic instability. One patient was operated in view of peritonitis. Most common type of the injury requiring operative intervention was a vertical shear fracture. One patient was managed with an immediate external fixator, while three underwent a definitive pelvis fixation at a later date. One patient was managed conservatively.

Conclusion: FAST has a high sensitivity for intra-abdominal bleeding. However, retroperitoneal hematoma in pelvic fractures can lead to false-positive FAST results. Therefore, we advocate for a comprehensive approach encompassing clinical judgment, additional imaging for stable patients, the engagement of a multidisciplinary team, and surgical expertise to ensure optimal patient care and outcomes.

Keywords: Abdominal trauma, focused assessment with sonography for trauma, pelvis fracture

Advanced trauma life support (ATLS) protocols prioritize rapid and accurate diagnosis, especially in severely injured patients where time is critical. Focused assessment with sonography for trauma (FAST) is an important adjunct for quickly detecting intra-abdominal hemorrhage [1]. Major pelvic fractures, characterized by unstable bony structures, can lead to severe bleeding from bony surfaces, pelvic venous plexuses, or pelvic arteries primarily located in the retroperitoneum [2]. The mortality rates associated with major pelvic fractures can be alarmingly high, reaching up to 40%, with concomitant abdominal organ injuries observed in nearly a third of cases [2,3]. Pelvic fractures are commonly associated with injuries to the bladder and urethra (14.6%), liver (10.2%), small bowel (8.8%), and spleen (5.8%) [3]. In this context, FAST has shown promising sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy in detecting intra-abdominal free fluid [2]. However, its reliability decreases in cases of major pelvic fractures with retroperitoneal hematoma, where identifying significant intra-abdominal injuries becomes challenging due to false positives. False-positive FAST results are a recognized challenge in the evaluation of pelvic trauma, often leading to unnecessary laparotomies. The prevalence of false-positive FAST findings in pelvic fractures has been reported in various studies, with rates ranging from 20% to 35% in some series [4,5]. This occurs due to the extravasation of blood from pelvic venous plexuses or fractures into the peritoneal cavity, mimicking intra-abdominal hemorrhage. In addition, the presence of physiological peritoneal fluid, pre-existing ascites, or technical limitations of ultrasound can contribute to misinterpretation. The consequence of false-positive FAST results includes increased rates of non-therapeutic laparotomies, which expose patients to unnecessary surgical risks, prolonged hospital stays, and higher healthcare costs [6,7]. Laparotomy itself carries inherent risks, including surgical site infections, wound dehiscence, intra-abdominal adhesions, and bowel obstruction [6,7]. Patients undergoing non-therapeutic laparotomies are also exposed to risks of bleeding, anesthetic complications, and thromboembolic events, which can further complicate their recovery. Any major surgery, including laparotomy, requires a post-operative recovery period. Unnecessary surgical interventions prolong hospital stays, increase the likelihood of intensive care unit admissions, and may delay the patient’s overall recovery, particularly in trauma patients who already have multiple injuries. This can also delay rehabilitation efforts, especially in patients with pelvic fractures who require early mobilization to prevent complications such as deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism. Non-therapeutic laparotomies contribute to unnecessary medical expenses, including operating room costs, anesthesia, post-operative care, and potential management of complications. Prolonged hospitalizations and the need for additional interventions, such as wound care or secondary surgeries, add to the economic burden on both healthcare systems and patients. Undergoing a major surgery that ultimately proves to be unnecessary can lead to significant emotional distress for patients and their families. The psychological impact includes increased anxiety, loss of trust in medical decision-making, and potential reluctance to seek surgical care in the future. Laparotomies, even when non-therapeutic, can lead to intra-abdominal adhesion formation, which increases the risk of future bowel obstructions and chronic abdominal pain. Patients who undergo unnecessary surgery are at a higher risk of repeat hospitalizations and further interventions due to these complications. In hemodynamically stable patients, additional investigations, such as whole-abdomen computed tomography (CT), can help localize the source of bleeding – whether from intra-abdominal injuries or pelvic fractures [8,9]. The decision-making process becomes critical in hemodynamically unstable patients presenting with free peritoneal fluid detected by FAST but unable to undergo abdominal CT for a definitive diagnosis. Trauma and orthopedic surgeons must weigh the risks and benefits of abdominal exploration. While exploration can confirm diagnoses, it can also disrupt pelvic tamponade and lead to uncontrollable bleeding, necessitating emergency embolization or pre-peritoneal packing and further morbidity. Non-therapeutic laparotomies are not rare in case of pelvic fractures with false-positive FAST [2]. The aim of this study was to assess the efficacy of FAST in detecting significant intra-abdominal hemorrhage, specifically in patients with major pelvic fractures, to guide appropriate management strategies. This involves distinguishing between the need for abdominal exploration and the appropriateness of less invasive interventions such as embolization and fixation. Such nuanced decision-making is crucial to optimizing outcomes and minimizing complications in trauma patients with major pelvic fractures.

The study aimed to identify the factors contributing to non-therapeutic laparotomies and evaluate their impact on patient outcomes. The study included all patients with pelvic fractures who underwent a laparotomy following a positive FAST result. Inclusion criteria were patients aged ≥18 years, hemodynamic instability on presentation, and positive findings on FAST suggestive of intra-abdominal fluid. Exclusion criteria included patients with penetrating abdominal trauma, incomplete medical records, and those who underwent non-surgical management despite a positive FAST result. The duration of the study spanned from June 2016 to December 2024. We conducted a comprehensive retrospective review of cases involving non-therapeutic laparotomies performed on patients with pelvic fractures and positive FAST results at our center. FAST results were interpreted by experienced trauma surgeons as either positive, negative, or indeterminate. Positive FAST findings included the presence of free intraperitoneal fluid in specific regions, such as the hepatorenal recess, splenorenal recess, or pouch of Douglas, without definitive evidence of organ injury. For indeterminate cases, further imaging, such as a contrast-enhanced CT scan, was employed for confirmation. A thorough review of the literature was also conducted to evaluate the accuracy of FAST in detecting significant intra-abdominal injuries, particularly in cases of unstable pelvic fractures, and its influence on decision-making regarding abdominal exploration. This allowed for a critical comparison of our findings with existing evidence, providing insights into optimizing the use of FAST and minimizing non-therapeutic laparotomies.

A thorough search of our prospectively maintained database revealed five non-therapeutic laparotomy cases in patients with pelvic fractures and positive FAST results (Table 1). We found five such cases between June 2016 and December 2024 that are described below.

The details of the five cases are given below.

Case 1

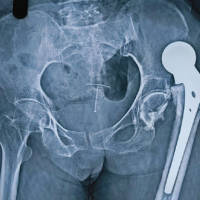

A 46-year-old female presented to the emergency department with unstable vitals and a vertical shear pelvis injury (Young and Burgess). The posterior fracture line passed through the sacral foramina, but she was neurologically intact. The results of the FAST test were positive (Fig. 1). We performed an exploratory laparotomy, which yielded negative results. After 2 days, we closed the wound and brought her back to the theater for final fixation. Using Stoppa’s approach with bilateral lateral windows, we attached a long reconstruction plate to the anterior pelvis. After flipping the patient, we performed lumbosacral fixation using a posterior midline approach (Fig. 2).

Case 2

A 26-year-old male with anteroposterior compression, vertical shear pelvis injury presented to the casualty. Here, too, the posterior fracture was trans-sacral. Given the patient’s instability and positive FAST result, we performed an exploratory laparotomy. We took him for definitive surgery after 3 days. We used two orthogonal plates to fix the anterior injury and a pair of iliosacral screws to fix the posterior injury (Fig. 3).

Case 3

On presentation to the emergency room, a 22-year-old male patient with vertical shear fracture of pelvis had a positive FAST result. His investigation was negative. Later, he received definite fixation in the form of iliosacral screws and posterior transiliac plating. After posterior fixation, the anterior injury did not open during examination under anesthesia, leading to the placement of no further implants anteriorly (Fig. 4). During the initial catheter insertion, a urethral injury occurred, leading to the placement of a suprapubic catheter without anterior exposure.

Case 4

A 40-year-old man claimed to have been involved in a car crash 10 h prior. On presentation, the patient had low blood pressure, tachycardia, and hemodynamic instability. Following the initial resuscitation, the patient responded. However, the initial FAST scan revealed pelvic-free fluid. Pelvic radiography revealed a diastasis of the pubis symphysis, as well as a fracture of the right-sided superior and inferior pubic rami. We performed an abdominal contrast CT scan after adequate resuscitation. The CT scan did not reveal any evidence of a solid organ lesion. However, a subsequent clinical examination revealed signs of peritonitis, prompting further exploration of the patient. We identified a large, stable retroperitoneal hematoma and determined that no further intervention was required. The risk of abdominal compartment syndrome (ACS) prevented the closure of the abdomen. The patient had a prolonged hospital stay due to the open abdomen and required further interventions for abdominal closure. Due to its impact, we treated the pelvic fracture non-operatively using a pelvic binder.

Case 5

A 32-year-old male presented with blunt trauma to the abdomen following a fall from the bike. At the initial presentation, he was unstable with tenderness in the lower part of the abdomen. The initial FAST scan revealed free fluid in the pelvis. The patient also fractured the right-sided sacroiliac joint with vertical displacement. The patient underwent an exploratory laparotomy due to persistent tachycardia. However, we managed the extensive retroperitoneal hematoma without further exploration, as there was no evidence of any solid organ or hollow viscus injury. As in the previous case, the risk of ACS prevented the closure of the abdomen. We used external fixators to fix the pelvic fracture. Unfortunately, the patient succumbed to his injuries within <24 h of his presentation.

In patients with major pelvic fractures, identifying associated intra-abdominal injuries is crucial, as these injuries occur in about 30% of cases and are more frequent in severe fractures [10]. However, when patients are hemodynamically unstable, quick identification of the bleeding source is vital. The first step recommended by the ATLS guidelines is performing a FAST to detect free fluid, which can indicate hemoperitoneum. In a study of nearly 20,000 patients, Netherton et al. reported a pooled FAST sensitivity of 74.2% and a pooled specificity of 97.6% [11]. While FAST can detect fluid, it cannot pinpoint the exact injury site, posing a dilemma for surgeons in determining the source of hemorrhage [12]. Stable patients with suspected intra-abdominal injuries and major pelvic fractures prefer whole-abdominal CT scans [8]. However, in unstable patients, this may not be feasible, leading to reliance on FAST findings alone. FAST is a rapid, non-invasive tool for detecting intra-abdominal bleeding. It is extremely useful in blunt abdominal trauma with concurrent solid organ injuries. It can help guide initial resuscitation and triage in unstable patients. However, it cannot differentiate between intraperitoneal and retroperitoneal hemorrhage. It may lead to false-positive results due to retroperitoneal hematomas, prompting unnecessary laparotomies. It also has limited sensitivity for hollow viscus injuries. We suggest, in stable patients with positive FAST and pelvic fractures, perform contrast-enhanced CT to assess the source of free fluid before committing to laparotomy. Laparotomy should be reserved for patients with peritonitis or signs of ongoing intra-abdominal hemorrhage that is not explained by retroperitoneal hematoma alone. Angiographic embolization should be considered for pelvic hemorrhage instead of surgical exploration when appropriate. Given the high mortality risk associated with delayed surgery in unstable patients with intra-abdominal injuries, most experts recommend immediate exploratory laparotomy. This urgency is crucial to promptly identifying and addressing life-threatening conditions, minimizing the risks of further complications, and optimizing patient outcomes. However, this strategy may not be beneficial for patients with pelvic fractures who do not have intra-abdominal injuries. Often, during exploratory laparotomy, surgeons encounter a pelvic retroperitoneal hematoma, which can inadvertently leak into the intraperitoneal space. While infrequent, non-therapeutic laparotomies can lead to complications such as pelvic tamponade loss and increased bleeding [13]. In this scenario, the usual recommendation is abdominal exploration through an upper midline incision to avoid disrupting pelvic tamponade while addressing potential injuries. Moreover, hybrid angiosuites, although beneficial by allowing simultaneous laparotomy and angiography, are not widely available, even in leading medical centers globally. Therefore, we recommend a multidisciplinary approach involving both trauma and orthopedic surgeons to address this complex issue. Research has shown that the use of an external fixator to stabilize the pelvis reduces bleeding and is a valuable component of management [14]. Our center maintains a low rate of non-therapeutic laparotomies thanks to our multidisciplinary approach, where trauma surgeons, neurosurgeons, and orthopedic surgeons evaluate all trauma patients. However, despite this protocol, five patients, including one fatality, underwent non-therapeutic laparotomies. Our analysis, alongside a meta-analysis of multiple studies, highlights a strong correlation between positive results from FAST and significant intra-abdominal injuries necessitating exploratory surgery [2] Nonetheless, it is crucial to note that retroperitoneal hematoma in pelvic fractures can lead to false-positive FAST results. The probable cause of false-positive FAST results is pelvic fractures with retroperitoneal hematomas. All cases involved significant pelvic fractures, often with trans-sacral or vertical shear patterns. Retroperitoneal hematomas associated with these fractures likely contributed to positive FAST results, despite the absence of intraperitoneal organ injury. Exploratory laparotomies in these patients did not reveal any intra-abdominal organ injuries, suggesting that the positive FAST findings were due to retroperitoneal hemorrhage rather than intrabdominal fluid. Many patients had transient instability or persistent tachycardia, leading to an aggressive surgical approach. Some cases required open abdomen management due to concerns about ACS from large retroperitoneal hematomas. One case had a urethral injury, which may have influenced clinical decision-making but was not directly related to the false-positive FAST. Therefore, we advocate for a comprehensive approach encompassing clinical judgment, additional imaging for stable patients, the engagement of a multidisciplinary team, and surgical expertise to ensure optimal patient care and outcomes. The broader implications of the findings include better surgical decision-making. These cases highlight the pitfalls of relying solely on FAST in pelvic trauma. The presence of free fluid may not always necessitate an exploratory laparotomy. A more selective approach incorporating contrast-enhanced CT scans in hemodynamically stable patients could help avoid unnecessary surgeries. Trauma teams should recognize that retroperitoneal bleeding can mimic intra-abdominal injury on FAST. A multidisciplinary approach (involving trauma surgeons, orthopedic surgeons, and radiologists) is critical for differentiating true intra-abdominal injuries from isolated pelvic trauma. This study’s contributions are significant, yet it is crucial to acknowledge its limitations, notably due to the retrospective nature of the included studies and the relatively small sample size from our institution.

FAST is a powerful tool for assessing the risk and predicting the outcome in individuals who are highly suspected of having abdominal injuries. Despite its excellent specificity, this test can produce false-positive results, particularly in cases of retroperitoneal hematoma caused by sacral/pelvic fractures. Hence, it is imperative for trauma surgeons, general surgeons, and orthopedic surgeons to collaborate in evaluating the patient to prevent unnecessary laparotomy. If the patient’s condition allows, it is advisable to perform a CT scan in this predicament.

FAST is a simple and efficient method for identifying intra-abdominal bleeding. However, in cases of major pelvic fractures, particularly those involving retroperitoneal hematoma, accurately identifying serious intra-abdominal injuries can be difficult due to the occurrence of false positives, which can occasionally result in unnecessary laparotomies.

References

- 1.Desai N, Harris T. Extended focused assessment with sonography in trauma. BJA Educ 2018;18:57-62. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 2.Chaijareenont C, Krutsri C, Sumpritpradit P, Singhatas P, Thampongsa T, Lertsithichai P, et al. FAST accuracy in major pelvic fractures for decision-making of abdominal exploration: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Med Surg (Lond) 2020;60:175-81. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 3.Demetriades D, Karaiskakis M, Toutouzas K, Alo K, Velmahos G, Chan L. Pelvic fractures: Epidemiology and predictors of associated abdominal injuries and outcomes. J Am Coll Surg 2002;195:1-10. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 4.Schwed AC, Wagenaar A, Reppert AE, Gore AV, Pieracci FM, Platnick KB, et al. Trust the FAST: Confirmation that the FAST examination is highly specific for intra-abdominal hemorrhage in over 1,200 patients with pelvic fractures. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2021;90:137-42. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 5.Abu-Zidan FM. Is focused assessment with sonography for trauma useful in patients with pelvic fractures? J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2021;91:e35-6. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 6.Renz BM, Feliciano DV. Unnecessary laparotomies for trauma: A prospective study of morbidity. J Trauma 1995;38:350-6. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 7.Sosa JL. Unnecessary laparotomies for trauma: A prospective study of morbidity. J Trauma 1995;39:397-8. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 8.Hamidi MI, Aldaoud KM, Qtaish I. The role of computed tomography in blunt abdominal trauma. Sultan Qaboos Univ Med J 2007;7:41-6. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 9.Vaidya R, Waldron J, Scott A, Nasr K. Angiography and embolization in the management of bleeding pelvic fractures. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2018;26:e68-76. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 10.Gad MA, Saber A, Farrag S, Shams ME, Ellabban GM. Incidence, patterns, and factors predicting mortality of abdominal injuries in trauma patients. N Am J Med Sci 2012;4:129-34. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 11.Netherton S, Milenkovic V, Taylor M, Davis PJ. Diagnostic accuracy of eFAST in the trauma patient: A systematic review and meta-analysis. CJEM 2019;21:727-38. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 12.Alramdan MH, Yakar D, IJpma FF, Kasalak Ö, Kwee TC. Predictive value of a false-negative focused abdominal sonography for trauma (FAST) result in patients with confirmed traumatic abdominal injury. Insights Imaging 2020;11:102. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 13.Berg RJ, Okoye O, Teixeira PG, Inaba K, Demetriades D. The double jeopardy of blunt thoracoabdominal trauma. Arch Surg 2012;147:498-504. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 14.Encinas-Ullán CA, Martínez-Diez JM, Rodríguez-Merchán EC. The use of external fixation in the emergency department: Applications, common errors, complications and their treatment. EFORT Open Rev 2020;5:204-14. [Google Scholar | PubMed]