Tenosynovial GCT though a rare occurrence, should have a high index of suspicion, hence should be diagnosed radiologically and to be treated surgically with close clinical and radiological follow-up for recurrence.

Dr. Kishore Ragavendra Rajesh, Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, #17/6a, Shanmuganar Salai, Gill Nagar, Choolaimedu, Chennai- 94, Tamil Nadu, India. E-mail: kishoreragavrajesh@gmail.com

Introduction: Tenosynovial giant cell tumors (TS-GCTs) are primary soft-tissue tumors that arise from the synovium of joints, bursae, and tendon sheath. They are classified into two major forms – localized and diffuse types with varied clinical presentation and treatment protocol.

Case Report: A 38-year-old gentleman presented with complaints of left thigh swelling and pain since 18 months. He underwent aspiration and a surgical procedure elsewhere without much improvement. Diagnosis was confirmed on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Surgical resection was done and specimen was correlated histopathologically. Another 15-year-old boy presented with complaints of right knee pain and swelling since 5 months. MRI was done which showed knee effusion with synovial thickening for which aspiration was done and started on antibiotics but symptoms persisted. Hence, surgical resection and biopsy was done which was confirmed to be TS-GCT. Both patients regained full knee movements postoperatively and were uneventful.

Conclusion: The mainstay of treatment of TS-GCT diffuse type is complete open surgical resection with role of adjuvant radiotherapy/chemotherapy being controversial.

Keywords: Tenosynovial giant cell tumor, tenosynovial-giant cell tumor of knee, diffuse type, open biopsy, magnetic resonance imaging, wide resection, radiotherapy, chemotherapy.

Tenosynovial giant cell tumors (TS-GCT), also known as pigmented villo-nodular synovitis (PVNS), are primary soft-tissue tumors that arise from the synovium of joints, bursae, and tendon sheath. They are benign (non-cancerous), do not metastasize, and are locally aggressive. Giant cell tumor of soft tissues was initially classified under “malignant giant cell tumor of soft parts” [1] eventually reclassified as “giant cell tumor of low malignant potential” as they lack cytological atypia, even in the presence of increased mitotic activity and vascular invasion [2]. They are clinically and histologically similar to giant cell tumor (GCT) of bone [3]. A category of “pigmented villo-nodular synovitis, bursitis, and tenosynovitis” was proposed to group together lesions previously known under different names according to location [4]. Most authors favored a non-tumoral reactive etiology, as an implication of inconspicuous microtrauma and associated lipid disorder [5], while some suggesting a tumoral process, with tumorous proliferation of fibroblasts and histiocytes [6]. Tenosynovial giant cell tumors (TGCT) has a slight female preponderance (female: male = 2:1) and affects a relatively younger age group mainly between 30 and 50 years, although it can occur at any age [7,8]. They are classified into two major forms – localized and diffuse. Diffuse type TS-GCT (D-TS-GCT) intra-articular forms are likely to spread diffusely, developing a multi-compartmental growth pattern involving at least two contiguous intra-articular synovial recesses. D-TS-GCT extra-articular growth pattern mainly occur secondary to intra-articular extension through trans-capsular fenestrations [9]. Extensive en bloc surgery, as practiced for other malignant tumors, is not indicated. Resection may be total or subtotal, depending on the disease’s history (primary or recurrent), clinical expression, diffuse or localized, nodular nature, extension, location, and progression [10]. For localized type TS-GCT (L-TS-GCT), either arthroscopic resection or open surgery yields good tumor control. Treatment of diffuse forms is more difficult especially in the knee with high local recurrence rate of 27.7% [11]. The primary aim in treating intra-articular D-TS-GCT is to remove all abnormal synovium, thus preventing local recurrence and ultimately reducing risk of arthritis whereas in extra-articular D-TS-GCT, it is necessary to prevent the destruction of the affected tendon or bursa. While D-TS-GCT exhibits neoplastic features with clonal cytogenetic abnormalities, it shares many characteristics with inflammation related to rheumatoid arthritis (RA). D-TS-GCT is likely situated in an intermediate state between inflammatory and neoplastic process [12]. Hence, non-specific anti-inflammatory drugs were used initially without much success and later on switching over to colony-stimulating factor 1 (CSF1) receptor blocking agents which are expected to show promising results in near future. Patients are to be closely followed up for clinical recurrence as it is the inherent nature of this tumor. Two patients of two different age groups presenting with this rare clinical condition and management strategy followed are being discussed in this article.

Case 1 (Fig. 1)

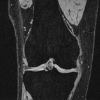

A 38-year-old male presented with complaints of the left thigh swelling and pain since 18 months. The initial fluid aspiration followed by excision biopsy procedure was done elsewhere 2 months back without much improvement. Intraoperative photo revealed a grayish-white globular mass over lateral aspect of distal thigh which was histopathologically reported as TS-GCT. Patient presented to us with a large soft ill defined swelling over distal thigh with a lateral healed surgical scar. Knee range of movements (ROM) were terminally restricted without neurovascular deficit. X-ray showed enlarged soft-tissue

shadow over distal femur extending up to patella without any bony changes. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed diffuse frond like T1/T2 ypointense synovial thickening in knee joint with large thick-walled hemorrhagic collection in vastus medialis and intermedius with possible sequestrated synovium within. Since the previous biopsy reports and slides were available, after discussion with the surgical oncologist, it was decided to perform marginal/wide excision of the lesion. The tumor was exposed by an anteromedial longitudinal incision. Predominantly marginal excision of tumor was done without disturbing the tumor capsule as femoral artery was close to the tumor medially. Vasti and rectus were preserved to whatever extent possible. The tumor which was extending into the joint anteriorly was excised in-Toto along with the visible synovium. There was a debate as to whether radiotherapy and chemotherapy were required for this patient but they were not given for the patient after reviewing the available literature [11,13-16]. Histopathological examination (HPE) was done showed and confirmed features suggestive of TS-GCT. He was advised to continue his professional activities after 3 months of surgery. At 8 months follow-up, his knee flexion was 110° with no extensor lag and MRI thigh showed no recurrent/residual lesion with only mild-moderate knee joint effusion. His

Musculoskeletal Tumor Society (MSTS) score (total score = 30) improved from pre-operative value of 10 to score of 18 at 3rd post-operative month and 29 at 1 year follow-up.

Case 2 (Fig. 2)

A 15-year-old male presented with complaints of right knee pain and swelling since 5 months. X-ray had no bony abnormality. Symptoms did not subside following conservative management; hence, MRI was done

which showed significant knee joint effusion with synovial thickening – probably inflammatory etiology for which aspiration was done and started on antibiotics but symptoms persisted. The patient underwent right knee subtotal synovectomy and open biopsy. Intraoperative specimen showed multiple intra-articular grayish-white soft-tissue nodules. HPE was done showed features suggestive of TS-GCT. The patient obtained full knee ROM with no extensor lag and was back to his regular scholastic and sports activities by 3rd post-operative month. One year post-operative follow-up was uneventful. His MSTS score (total score = 30) improved from pre-operative value of 16 to score of 26 at 3rd post-operative month and 30 at 1 year follow-up.

TS-GCT and the more aggressive PVNS (now categorized as localized and diffuse type TS-GCT, respectively as per World Health Organization classification of soft tissue and bone tumors) are essentially the same. There was no clear cut distinction identified between the two subtypes histopathologically; hence, diagnosis can be made only clinically and radiologically. TGCT subtypes share a common underlying pathogenesis, mainly related to a colony-stimulating factor-1 translocation (overexpression) involving locus 1p 13 (in 2–16% of cells), thus creating an aggressive multinuclear “landscape” of TS-GCT [17]. There are no environmental, genetic, occupational, lifestyles, demographic, or regional risk factors involved in the development of these tumors. 195 Imaging of D-TS-GCT constitutes conventional radiographs of knee which are usually normal, sometimes showing features of osteoarthritis and joint erosion [12]. Although ultrasound is not much useful due to low specificity, it can be used to perform image-guided biopsies. MRI is the imaging modality of choice

to diagnose D-TS-GCT, to plan surgeries with adjuvant radiotherapy/chemotherapy, and to assess residual lesions and local recurrence present after synovectomy or treatment response to chemotherapy. Furthermore, cartilage invasion, cortical bone erosions, muscular/tendinous, ligament, and neurovascular involvement were proposed as parameters that determine the severity of D-TS-GCT [17]. D-TS-GCT is more prone to bleeding (compared to L-TS-GCT); hence,

hemarthrosis is a common finding expressed as low-signal intensity (SI) on both T1-weighted imaging and fluid-sensitive sequences. Hemorrhage constitutes classic D-TS-GCT imaging hallmark mostly detected as “blooming artifacts” (secondary to hemosiderin deposition) – presents as enlarged and disproportionately lower SI of blood deposits on gradient echo

sequences compared to spin-echo sequences. Although pathognomonic for diagnosis, its absence does not rule out TS GCT [18]. Common post-operative changes include skin thickening, fat stranding or inflammation in Hoffa, subcutaneous, and intramuscular edema. Diffuse synovial thickening is equivocal for D-TS-GCT residual disease within the first 6 months due to associated reactive synovitis. Growing, enhancing solid, and nodular synovial thickening should raise suspicion of disease recurrence [12].

Checklists on follow-up MRI following various types of treatment [19] are shown in Table 1. Comparison between localized and D-TS-GCT is depicted in Table 2.

The differential diagnosis of extra-articular D-TS-GCT is difficult due to their rarity. Some encountered clinically and radiologically include tophaceous gout, chronic RA, synovial chondromatosis, lipoma arborescens, synovial hemangioma, hemophilic arthropathy, and emosiderotic synovitis [19]. Our pre-operative differential diagnosis in case 1 was soft-tissue sarcoma and case 2 was chronic synovitis probably due to tubercular etiology. It is difficult to achieve a balance between complete tumor resection and preservation of knee function. Hence, acceptable knee function can be obtained if total knee arthroplasty (TKA) is done after complete tumor resection [20]. However, the outcomes of TKA following resection of a portion of the quadriceps may be poor. TKA combined with synovectomy was considered an effective treatment for advanced TGCT with degenerative lesions [21]. However, patients with iffuse TGCT who underwent TKA experienced more surgical complications, including stiffness and infection compared to patients with osteoarthritis who underwent TKA [13]. In all cases, pre-operative MRI extension assessment is essential to plan treatment strategy: Extension outside the joint or in posterior recess (in popliteal fossa) contraindicates isolated arthroscopic treatment [10,11,14]. A systematic review makes conclusions that arthroscopic excision is effective in minimizing morbidity and surgery-related complications, while an open surgical technique provides a more successful complete resection with a lower incidence of local recurrence [15]. A comprehensive treatment protocol for the new clinical classification for TGCT of the knee [20] is described in Illustration 1.

Radiation therapy (RT) is the most widely used adjuvant; RT (external and intra-articular also known as isotopic synoviorthesis) seems to reduce recurrence in D-TS-GCT, especially when synovectomy was partial [11]. External RT uses 30–50 Gy in 20 sessions [22], which is only less useful despite good disease control [10]. Intra-articular RT is not recommended in case of bone extension or if arthroplasty is liable to be performed; it may be considered after partial synovectomy and in diffuse forms [23]. However, the synoviorthesis-surgery sequence lacks efficacy in the knee (30% recurrence) compared to other joints (9% recurrence) despite theoretic risk of malignant transformation following RT [11]. Review of literature suggests that RT (especially external) provides benefit and more clinical studies are warranted to determine its currently unknown therapeutic value. Systemic therapy, valuable as part of a multidisciplinary approach [16] is based on developing targeted therapies and studying on the underlying molecular mechanisms of TS GCTs. Non-specific anti-inflammatory treatment by anti

tumor necrosis factor-alpha was the first medical treatment to be described. Although surgery is the primary treatment option, emerging systemic therapies targeting CSF1-receptor are valuable. Since CSF1 gene expression was elevated in most TGCT cases, a structural blockade of CSF-1 receptor tyrosine kinase resulted in a prolonged regression in tumor volume in

most patients [24,25]. One such drug, pexidartinib provides a novel non-surgical option to address intra-articular D-TS-GCT [16,20], thus improving ROM, leading to its inclusion in Food and Drug Administration approved treatment protocol.

The mainstay of treatment of D-TS-GCT is complete open surgical resection (marginal/wide) with role of adjuvant radiotherapy and chemotherapy being controversial.

TS-GCT though presenting with similar biopsy features of GCT of bone should be radiologically diagnosed and treated appropriately based on specific type. Meticulous clinico-radiological follow-up is required due to high risk of recurrence (especially D-TS-GCT) with role of adjuvant radiotherapy and chemotherapy still being controversial.

References

- 1.Salm R, Sissons HA. Giant-cell tumours of soft tissues. J Pathol 1972;107:27-39. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Folpe AL, Mooris RJ, Weiss SW. Soft tissue giant cell tumor of low malignant potential: A proposal for the reclassification of malignant giant cell tumor of soft parts. Mod Pathol 1992;12:894-902. [Google Scholar]

- 3.O’Connell JX, Wehrli BM, Nielsen GP, Rosenberg AE. Giant cell tumors of soft tissue: A clinicopathologic study of 18 benign and malignant tumors. Am J Surg Pathol 2000;24:386-95. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jaffe HL, Lichtenstein L, Sutro CJ. Pigmented villonodular synovitis, bursitis and tenosynovitis: A discussion of the synovial and bursal equivalents of the tenosynovial lesion commonly denoted as xanthoma, xanthogranuloma, giant cell tumor or myeloplaxoma of the tendon sheath, with some consideration of this tendon sheath lesion itself. Arch Pathol 1941;31:731-65. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Byers PD, Cotton RE, Deacon OW, Lowy M, Newman PH, Sissons HA, et al. The diagnosis and treatment of pigmented villonodular synovitis. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1968;50:290-305. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rao AS, Vigorita VJ. Pigmented villonodular synovitis (Giant-cell tumor of the tendon sheath and synovial membrane). A review of eighty-one cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1984;66:76-94. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mastboom MJ, Verspoor FG, Verschoor AJ, Uittenbogaard D, Nemeth B, Mastboom WJ, et al. Higher incidence rates than previously known in tenosynovial giant cell tumors. Acta Orthop 2017;88:688-94. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ehrenstein V, Andersen SL, Qazi I, Sankar N, Pedersen AB, Sikorski R, et al. Tenosynovial giant cell tumor: Incidence, prevalence, patient characteristics, and recurrence. A registry-based cohort study in Denmark. J Rheumatol 2017;44:1476-83. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim JH, Lee SK, Kim JY. MRI prediction model for tenosynovial giant cell tumor with risk of diffuse-type. Acad Radiol 2023;30:2616-24. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gouin F, Noailles T. Localized and diffuse forms of tenosynovial giant cell tumor (formerly giant cell tumor of the tendon sheath and pigmented villonodular synovitis). Orthop Traumatol Surg Res 2017;103:S91-7. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mollon B, Lee A, Busse JW, Griffin AM, Ferguson PC, Wunder JS, et al. The effect of surgical synovectomy and radiotherapy on the rate of recurrence of pigmented villonodular synovitis of the knee: An individual patient meta-analysis. Bone Joint J 2015;97:550-7. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Robert M, Farese H, Miossec P. Update on tenosynovial giant cell tumor, an inflammatory arthritis with neoplastic features. Front Immunol 2022;13:820046. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Casp AJ, Browne JA, Durig NE, Werner BC. Complications after total knee arthroplasty in patients with pigmented villonodular synovitis. J Arthroplasty 2019;34:36-9. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ogilvie-Harris DJ, McLean J, Zarnett ME. Pigmented villonodular synovitis of the knee. The results of total arthroscopic synovectomy, partial, arthroscopic synovectomy, and arthroscopic local excision. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1992;74:119-23. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Quaresma MB, Portela J, Soares Do Brito J. Open versus arthroscopic surgery for diffuse tenosynovial giant-cell tumours of the knee: A systematic review. EFORT Open Rev 2020;5:339-46. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Healey JH, Bernthal NM, Van De Sande M. Management of tenosynovial giant cell tumor: A neoplastic and inflammatory disease. J Am Acad Orthop Surg Glob Res Rev 2020;4:e20.00028. [Google Scholar]

- 17.West RB, Rubin BP, Miller MA, Subramanian S, Kaygusuz G, Montgomery K, et al. A landscape effect in tenosynovial giant-cell tumor from activation of CSF1 expression by a translocation in a minority of tumor cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2006;103:690-5. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Crim J, Dyrof SL, Stensby JD, Evenski A, Layfeld LJ. Limited usefulness of classic MR findings in the diagnosis of tenosynovial giant cell tumor. Skeletal Radiol 2021;50:1585-91. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Spierenburg, G, Suevos Ballesteros, C., Stoel, B.C., Navas Canete, A., Gelderblom, H., van de Sande, M.A.J., van Langevelde, K. MRI of diffuse-type tenosynovial giant cell tumour in the knee: A guide for diagnosis and treatment response assessment. Insights Imaging 2023, 14, 22. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zheng K, Yu XC, Hu YC, Xu M, Zhang JY. A new simple and practical clinical classification for tenosynovial giant cell tumors of the knee. Orthop Surg 2022;14:290-7. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lei P, Sun R, Liu H, Zhu J, Wen T, Hu Y. Prognosis of advanced tenosynovial giant cell tumor of the knee diagnosed during total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2017;32:1850-5. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Griffin AM, Ferguson PC, Catton CN, Chung PW, White LM, Wunder JS, et al. Long-term outcome of the treatment of high-risk tenosynovial giant cell tumor/pigmented villonodular synovitis with radiotherapy and surgery. Cancer 2012;118:4901-9. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ottaviani S, Ayral X, Dougados M, Gossec L. Pigmented villonodular synovitis: A retrospective single-center study of 122 cases and review of the literature. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2011;40:539-46. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tap WD, Wainberg ZA, Anthony SP, Ibrahim PN, Zhang C, Healey JH, et al. Structure-guided blockade of CSF1R kinase in tenosynovial giant-cell tumor. N Engl J Med 2015;373:428-37. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brahmi M, Vinceneux A, Cassier PA. Current systemic treatment options for tenosynovial giant cell tumor/pigmented villonodular synovitis: Targeting the CSF1/CSF1R axis. Curr Treat Options Oncol 2016;17:10. [Google Scholar]