Management of inferior glenohumeral dislocation is complex due to associated injuries, particularly in patients with prior shoulder pathology. In cases of neuropraxia or plexopathy, delayed injury to previously repaired rotator cuff tendons must be suspected and can require late operative repair

Dr. Robert Hall III, Department of Orthopedics and Physical Rehabilitation, University of Massachusetts Medical Center, 55 Lake Avenue North, Worcester - 01655, Massachusetts, United States. E-mail: rrhall95@gmail.com

Introduction: Inferior glenohumeral dislocations are rare injuries, comprising <1% of shoulder dislocations. While their presentation is rare, these injuries commonly result in associated bony injuries, neuropraxia, and tendon injuries. Proper management of such injuries typically requires advanced imaging and consultation with multiple specialists. Here, we present the unique case of inferior glenohumeral dislocation and resultant brachial plexopathy in a patient with previous rotator cuff repair that required subsequent operative management for delayed sequelae of his injury. Interestingly, initial magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) demonstrated the integrity of the prior repair, and there was no clinically significant rotator cuff pathology acutely following the injury. Given the persistent weakness in external reduction and abduction, a repeat MRI was obtained, demonstrating rotator cuff tearing and requiring operative management. Excellent outcome was achieved at 1 year.

Case Report: A 62-year-old male with a history of rotator cuff repair presented with inferior glenohumeral dislocation and posterior cord brachial plexopathy after a bicycle accident. Closed reduction was performed. Acute MRI demonstrated intact rotator cuff repair. Repeat MRI demonstrated rotator cuff injury, which required late operative intervention. Electromyography and clinical examination 1 year following his injury demonstrated continued improvement in his posterior cord plexopathy with complete resolution of pain and ability to return to work and perform activities of daily living as assessed by American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons score.

Conclusion: Inferior shoulder dislocations are rare injuries that may be associated with bony injuries, neuropraxia, and tendon injuries. These associated complications can result in delayed presentation of rotator cuff pathology, particularly in the setting of prior rotator cuff repair. Recovery of the neuropraxia can be expected but frequently requires specialist evaluation and invasive testing. Despite its delayed presentation, repair of the rotator cuff tendon paired with trapezius transfer and neurolysis resulted in an excellent outcome.

Keywords: Inferior glenohumeral dislocation, brachial plexopathy, deltoid-induced rotator cuff tear.

The anatomy of the glenohumeral joint allows wide arcs of motion in multiple planes. Associated with these wide motion arcs is instability [1]. As such, glenohumeral joint dislocations comprise half of all joint dislocations, making them the most commonly dislocated joint in the body [2]. About 90% of traumatic glenohumeral dislocations are anterior [3], with inferior shoulder dislocations making up only 0.5% of traumatic glenohumeral dislocations [4]. Inferior glenohumeral dislocation, termed “luxatio erecta humeri,” has been associated with significant rates of associated injuries. Review articles report neurological injuries at a rate of 29%, with the most frequent injury affecting the axillary nerve [5]. Associated fractures are also common, with proximal humerus fractures occurring at reported rates of 39% and scapular fractures occurring in 8% of patients [6]. Hill-Sachs injuries have been described in 4% of luxatio erecta [7], but such articles detail traditional Hill-Sachs location on the posterosuperior humeral head. Contrastingly, the presented patient sustained an osseous defect in his anterolateral humeral head. Given the rare nature of luxatio erecta, there is a paucity of literature detailing the complete scope of associated injuries and their management. Here, we present the case of a patient who presented as trauma activation to a level one trauma center with an inferior glenohumeral dislocation and concurrent brachial plexopathy. The initial presentation was consistent with sensorimotor axillary and radial nerve palsies with a Hill-Sachs variant on the anteromedial humeral head. Prior rotator cuff repair was radiographically intact on initial follow-up. However, subsequent follow-up 8 months following the injury demonstrated rotator cuff retear, which required operative roator cuff repair, trapezius transfer, and neurolysis. As the patient denied repeat trauma, we hypothesize that deltoid weakness secondary to plexopathy resulted in increased rotator cuff strain and ultimate repair failure. One year following the injury, the patient demonstrated electromyography (EMG) evidence of reinnervation and clinical improvement of nerve palsies. Further, he experienced complete recovery of function, return to work, and resolution of pain. We believe that deltoid weakness resulted in increased demand on the previously repaired rotator cuff, leading to failure

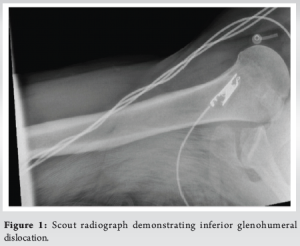

A 62-year-old right-hand dominant male with a history of prior right arthroscopic supraspinatus and infraspinatus repair 30 months prior and no active medical problems presented as a trauma activation with obvious deformity of his right arm after a fall off his bicycle while trail riding. Immediate examination in the trauma bay revealed the shoulder abducted to 110° with the patient unable to extend the wrist or thumb. The sensation was diminished in the axillary and radial nerve distributions. Scout radiographs were obtained in the trauma bay and demonstrated inferior glenohumeral dislocation (Fig. 1). The patient was closed-reduced in the supine position by pulling in line traction with the abducted humerus while providing counter traction to the scapula. The arm was then adducted. This technique was originally described by Freundlich [8].

Post-reduction radiographs and computed tomography scans demonstrated a small area of impaction on the anterolateral humeral head (Fig. 2). Following closed reduction, radial and axillary nerve palsies persisted. The patient was initially managed non-operatively with a sling and wrist lace-up splint. He was discharged from the emergency department on the date of injury after completion of his trauma workup.

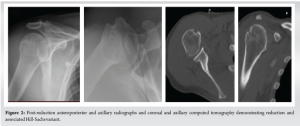

At the first follow-up 5 days following the injury, the patient continued to have diminished sensation in the axillary and radial distributions. He demonstrated no ability to extend the wrist or the fingers. Elbow flexion and extension strength was 5/5. Shoulder examination revealed 4/5 abduction strength, 5/5 strength on internal rotation, and 1/5 strength on external rotation. As such, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was ordered to assess the integrity of his rotator cuff repair. This study was performed 6 days after his injury and demonstrated intact repairs of both the supraspinatus and infraspinatus with proximal tendinosis and a minor intramuscular tear of the subscapularis (Fig. 3).

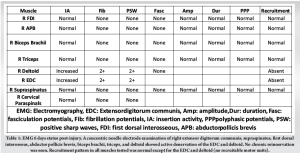

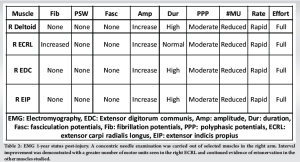

Outpatient EMG was also performed at 4 weeks following his injury and revealed denervation of the deltoid and extensor digitorum communis (EDC) with no recruitable motor units (Table 1), indicative of a right posterior cord brachial plexopathy. At the time, the patient was treated with a wrist lacer and physical therapy to avoid shoulder stiffness.

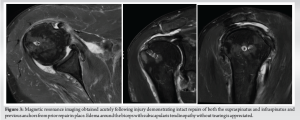

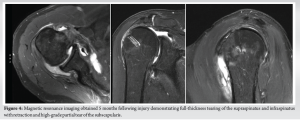

At a 5-month follow-up, the patient demonstrated 4/5 strength in the wrist extensors and EPL. Persistent anterior deltoid weakness was appreciated, with improving strength of the posterior and middle deltoid. Internal and external shoulder rotation was graded at 3/5, with positive liftoff and belly press tests. Given this new internal rotation weakness and persistent weakness in external rotation, a repeat MRI was obtained (Fig. 4) to evaluate for potential progressive tearing of the rotator cuff. This study demonstrated full-thickness tearing of the supraspinatus and infraspinatus with retraction and high-grade partial tear of the subscapularis. As the patient denied any inciting injury, rotator cuff retear in the setting of deltoid deficiency was suspected. Initial non-operative management was . At follow-up at 8 months status post his initial injury, the patient demonstrated a near-complete return of deltoid strength and wrist extension with 5/5 strength of the EDC and EPL. Persistent shoulder external rotation weakness with a 40° lag was appreciated. The patient was thus scheduled for arthroscopic rotator cuff repair with biceps tenodesis and trapezius transfer as initially described by Elhassan [9].

The patient underwent this procedure just under 9 months following his inferior shoulder dislocation. In detail, the patient was placed in the standard beach chair position. The lower trapezius was then harvested through an incision placed just distal to the medial spine of the scapula and extended medially for a centimeter (cm) and laterally for 4 cm. The trapezius tendon was identified and detached from the medial spine of the scapula, the lower trapezius was detached from the middle trapezius, and dissection was performed to obtain good excursion. A #2 suture tape was placed to reinforce the tendon. Simultaneously, an Achilles tendon allograft was prepared by placing it on the tendon preparation tower and placing two suture tapes of different colors through a 5-cm length of Achilles tendon allograft. An arthroscopic portion of the case was then initiated by creating standard anterior and lateral portals. Dissection was performed from lateral to medial toward the coracoid, and the pectoralis minor was identified and released. Then, with the use of a switching stick and arthroscopic scissors, a careful dissection of the brachial plexus was performed. Notably, the brachial plexus appeared to be encased with fascial tissues. The medial cord, the lateral cord, and the posterior cord were released and noted to be free of any impinging tissues. At this time, attention was directed toward performing the tendon transfer. The supraspinatus tendon was fully detached as expected, and the remnant of the tendon was very frayed and thus debrided. A full-thickness tear of the upper part of the subscapularis tendon was noted. An anterolateral portal was created to introduce a high-speed shaver and debride the superior portion of the lesser tuberosity. An anchor was then placed in the upper part of the lesser tuberosity. The sutures of the anchor were used to repair the upper part of the subscapularis tendon. An additional anchor was placed immediately lateral to the first anchor to reinforce the repair from the medial anchor. The biceps tendon appeared to be subluxation. Following subscapularis repair, the biceps tendon was reduced. Tenodesis of the biceps tendon was performed using a fully threaded, knotless anchor to allow the biceps tendon to act as a biological superior capsular reconstruction. The greater tuberosity was debrided to the bleeding bone. Finally, arthroscopic dissection was performed between the deltoid and infraspinatus toward the medial wound. Then, a long grasping instrument was introduced through the anterior portal, in between the deltoid and infraspinatus toward the medial wound. The sutures from the Achilles tendon allograft were retrieved. Thus, the Achilles tendon allograft was passing between the deltoid and infraspinatus toward the subacromial space. The medial sutures of the Achilles tendon allograft were fixed to the anterior medial footprint of the supraspinatus with a knotless anchor. The lateral sutures were fixed to the anterior lateral footprint of the supraspinatus with another anchor. The four sutures of the anterior medial anchor were passed from anterior to posterior through the remnant of the supraspinatus tendon. The sutures were passed on top of the Achilles tendon allograft and we anchored on the footprint of the supraspinatus. The shoulder was placed in adduction external rotation. The portion of the Achilles tendon allograft in the medial wound was split into half, the distal half was cut and discarded, and the proximal half was passed through the lower trapezius tendon effect on itself and sutured in place with #2 Ortho cord. The sutures that were placed in the lower trapezius tendon were further passed through the lower trapezius tendon and Achilles tendon construct. Excellent repair was achieved. The shoulder was placed in abduction external rotation, and the wound was closed in a layered fashion. The patient was immobilized in a gunslinger sling for 8 weeks, progressed to shoulder active assist range of motion for 8 weeks, and ultimately cleared for full active range of motion and strengthening. The patient also underwent a post-operative EMG 1-year status post his initial injury (Table 2) and 12-week status post his rotator cuff repair. This study demonstrated improvement in prior right posterior cord brachial plexopathy with continued evidence of reinnervation in all muscles studied.

At the final post-operative follow-up at 1 year, the patient demonstrated resolution of paresthesia, ability to participate in swimming exercises, and excellent range of motion measured at 150° elevation, 100° abduction, external rotation to 50°, and internal rotation to the L5 vertebrae. External rotation was graded at 5/5 strength. American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons (ASES) score was 100 out of 100 at the final follow-up.

Inferior glenohumeral dislocation is a rare presentation that usually occurs after high-energy trauma, resulting in a fall. Because of the mechanism of these injuries, such injuries are associated with the highest rate of associated injuries among glenohumeral dislocations [10]. Given their severity, it is critical that appropriate management of these injuries be described. However, the rare nature of inferior glenohumeral dislocations means that unique isolated injuries are still being reported. Case reports demonstrate that inferior glenohumeral dislocations commonly present with fractures or neurovascular injury, as is seen in our case [11]. Our case presented with the injured arm locked in 110° of abduction, with scout radiographs demonstrating the parallel positioning of the humeral shaft and scapular spine as described by Downey et al. [12]. A recent case report by Nambiar et al. describes associated injuries in glenohumeral injuries, reporting that 39% of patients demonstrate proximal humerus fractures, whereas 8% present with associated scapular fractures [6]. The most common site of injury was the greater tuberosity, which accounted for 77% of proximal humerus fractures. A biomechanical study of patients with chronic shoulder instability demonstrated that patients with both humeral and glenoid defects had decreased shoulder stability following Bankart repair [12]. Case reports have described the presence of Hill-Sachs lesions in inferior glenohumeral dislocations. In fact, a recent case report details the presence of an engaging Hill-Sachs lesion in a patient with inferior glenohumeral dislocation, which resulted in instability [13]. This patient was ultimately treated with 4 weeks of shoulder immobilization but was lost to follow-up before advanced imaging was obtained. In contrast to this presentation, our case demonstrated an anteromedial Hill-Sachs variant. The significance of these lesions on glenohumeral stability can be predicted by both size and location [14,15]. Given the location of the humeral head defect, it was not expected that this lesion would affect glenohumeral stability in the presented patient. Interestingly, our case had undergone a rotator cuff repair 30 months before his inferior shoulder dislocation. At the time of initial injury, MRI demonstrated intact supraspinatus and infraspinatus repair. During his follow-up course, the patient demonstrated continued weakness in external rotation strength, and a repeat MRI 5 months status post-injury demonstrated full-thickness supraspinatus and infraspinatus tears along with high-grade partial thickness subscapularis tears. As our case demonstrated, deltoid dysfunction secondary to posterior cord brachial plexopathy, his rotator cuff retear, and novel subscapularis pathology might have been due to increased strain on the rotator cuff muscles in the setting of deltoid dysfunction. It has been shown that patients with deltoid paralysis or shoulder hemiplegia demonstrate increased rates of fatigability [16] and increased rotator cuff tear rates [17]. Finally, our case demonstrated unique associated neurological symptoms as the result of posterior cord brachial plexopathy. Case reports detail that the axillary nerve is the most frequent nerve injured in inferior glenohumeral dislocations [18]. The literature review did demonstrate one prior instance of radial nerve palsy in a cohort of 38 inferior glenohumeral dislocations; however, individualized treatment was not described [19]. Our patient demonstrated continued sensorimotor palsy of both the axillary and radial nerves despite prompt reduction as a result of posterior cord plexopathy, which was confirmed by EMG performed immediately after injury. In similar radial nerve palsies in humeral shaft fractures, the treatment algorithm includes initial observation, with spontaneous recovery without surgical management observed in 71% of patients in a large cohort [20]. Contrastingly, our patient demonstrated continued weakness in shoulder internal and external rotation, with improvement in wrist extension and deltoid function. Additional imaging demonstrated new rotator cuff pathology, which was treated with operative repair and trapezius tendon transfer. At the time of that procedure, brachial plexus neurolysis was performed. At 1-year post-injury and 12 weeks status post-neurolysis, repeat EMG showed reinnervation clinically, and the patient demonstrated intact wrist and finger extension as well as shoulder abduction strength. The patient demonstrated excellent outcomes according to the ASES score and clinically had an excellent range of motion.

Given their rare nature, inferior glenohumeral dislocations may pose a challenge to treating physicians. Due to the nature of these injuries, they frequently present with associated injuries. Appropriate treatment of inferior glenohumeral dislocation relies on prompt reduction and identification. Here, we describe a case of a patient with a previously repaired rotator cuff who initially presented with multiple associated injuries. His management required multiple advanced imaging and nerve studies. Based on delayed sequelae of his injury, operative rotator cuff repair and brachial plexus neurolysis were performed. At the final follow-up, he experienced clinical improvement and a good outcome.

Inferior glenohumeral dislocation requires careful management from the treating physician. Delayed sequelae can occur and require operative management. When properly diagnosed and managed, resolution of plexopathy, resolution of pain, and return to work and high function are possible.

References

- 1.Vezeridis PS, Ishmael CR, Jones KJ, Petrigliano FA. Glenohumeral dislocation arthropathy: Etiology, diagnosis, and management. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2019;27:227-35. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hill B, Khodaee M. Glenohumeral joint dislocation classification: Literature review and suggestion for a new subtype. Curr Sports Med Rep 2022;21:239-46. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brophy RH, Marx RG. The treatment of traumatic anterior instability of the shoulder: Nonoperative and surgical treatment. Arthroscopy 2009;25:298-304. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Perron AD, Ingerski MS, Brady WJ, Erling BF, Ullman EA. Acute complications associated with shoulder dislocation at an academic emergency department. J Emerg Med 2003;24:141-5. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Groh GI, Wirth MA, Rockwood CA Jr. Results of treatment of luxatio erecta (inferior shoulder dislocation). J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2010;19:423-6. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nambiar M, Owen D, Moore P, Carr A, Thomas M. Traumatic inferior shoulder dislocation: A review of management and outcome. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg 2018;44:45-51. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yao F, Zhang L, Jing J. Luxatio erecta humeri with humeral greater tuberosity fracture and axillary nerve injury. Am J Emerg Med 2018;36:1926.e3-5. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Freundlich BD. Luxatio erecta. J Trauma 1983;23:434-6. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Elhassan B, Bishop A, Shin A. Trapezius transfer to restore external rotation in a patient with a brachial plexus injury. A case report. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2009;91:939-44. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sonanis SV, Das S, Deshmukh N, Wray C. A true traumatic inferior dislocation of shoulder. Injury 2002;33:842-4. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Downey EF Jr., Curtis DJ, Brower AC. Unusual dislocations of the shoulder. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1983;140:1207-10. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arciero RA, Parrino A, Bernhardson AS, Diaz-Doran V, Obopilwe E, Cote MP, et al. The effect of a combined glenoid and hill-sachs defect on glenohumeral stability: A biomechanical cadaveric study using 3-dimensional modeling of 142 patients. Am J Sports Med 2015;43:1422-9. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Panico LC, Roy T, Brustein J. Atypical presentation of an inferior shoulder dislocation with an engaging hill-Sachs lesion: A case report. Trauma Case Rep 2021;35:100529. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Provencher MT, Frank RM, Leclere LE, Metzger PD, Ryu JJ, Bernhardson A, et al. The hill-Sachs lesion: Diagnosis, classification, and management. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2012;20:242-52. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Burkhart SS, De Beer JF. Traumatic glenohumeral bone defects and their relationship to failure of arthroscopic bankart repairs: Significance of the inverted-pear glenoid and the humeral engaging Hill-Sachs lesion. Arthroscopy 2000;16:677-94. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Werthel JD, Bertelli J, Elhassan BT. Shoulder function in patients with deltoid paralysis and intact rotator cuff. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res 2017;103:869-73. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yi Y, Shim JS, Kim K, Baek SR, Jung SH, Kim W, et al. Prevalence of the rotator cuff tear increases with weakness in hemiplegic shoulder. Ann Rehabil Med 2013;37:471-8. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mallon WJ, Bassett FH 3rd, Goldner RD. Luxatio erecta: The inferior glenohumeral dislocation. J Orthop Trauma 1990;4:19-24. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ostermann RC, Joestl J, Hofbauer M, Fialka C, Schanda JE, Gruber M, et al. Associated pathologies following luxatio erecta humeri: A retrospective analysis of 38 cases. J Clin Med 2022;11:453. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shao YC, Harwood P, Grotz MR, Limb D, Giannoudis PV. Radial nerve palsy associated with fractures of the shaft of the humerus: A systematic review. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2005;87:1647-52. [Google Scholar]