Tapentadol nasal spray provides rapid, effective, and well-tolerated pain relief in patients with acute low back pain, significantly improving sleep quality and minimizing the need for rescue medication—supporting its potential as a safe, real-world treatment option.

Dr. Jatin Pawar, Department of Orthopedics, Dr. D. Y. Patil Hospital, Navi Mumbai, Maharashtra, India. Email: jatinpawar323@gmail.com

Introduction: Low back pain (LBP) is one of the most prevalent musculoskeletal conditions, leading to significant disability and healthcare burden worldwide. Effective pain relief with minimal side effects is crucial for improving patient outcomes. Tapentadol, a dual-mechanism opioid with µ-opioid receptor agonism and norepinephrine reuptake inhibition, has shown potent analgesic effects. Intranasal administration is an emerging route that ensures rapid absorption and enhanced efficacy. However, limited real-world data exist on the clinical use of tapentadol nasal spray (NS) in LBP management. This study aimed to evaluate the effectiveness and tolerability of tapentadol NS in patients with LBP.

Materials and Methods: This investigator-initiated, retrospective, real-world, observational study analyzed data from electronic medical records of adult LBP patients ≤65 years old treated with tapentadol NS for three consecutive days. The primary endpoint was change in score on the numeric pain rating scale (NPRS). The secondary endpoints were the proportion of patients requiring rescue medicine, change in global sleep quality score, and incidence of adverse events (AEs).

Results: A total of 300 patients were included in the analysis. The mean ± standard deviation NPRS pain score decreased significantly from 7.00 ± 0.80 on day 0 to 1.38 ± 0.45 on day 3, reflecting an 80.29% reduction (P < 0.001 for all changes from baseline). Notably, 99.00% of patients achieved >51% pain reduction by day 3. Similar trends were observed across different age groups and between male and female patients. Only 1.67% (5/300) of patients required rescue medication (intravenous paracetamol). A significant improvement in sleep quality (P < 0.001) was also noted. Importantly, no AEs were reported, indicating excellent tolerability of tapentadol NS.

Conclusion: Tapentadol NS demonstrated significant pain reduction and improvement in sleep quality in adult patients with LBP. The therapy was well tolerated, with no reported AEs and a minimal requirement for rescue medication. These findings suggest that tapentadol NS is an effective and safe treatment option for acute LBP. Future prospective studies with a longer follow-up period and a comparative analysis with other analgesic formulations are warranted to further establish its role in LBP management.

Keywords: Tapentadol, low back pain, tapentadol nasal spray, pain reduction, sleep quality, tolerability.

Low back pain (LBP) is the leading cause of disability, with approximately 1 in 13 (or 619 million) people affected globally in 2020, accounting for 8.1% of all-cause years living with disability. The projected estimate of affected individuals for 2050 is 843 million, with Asia being one of the regions expected to have the greatest growth in terms of diagnosed cases. The growing and aging populace is the chief contributor to the ever-increasing burden of LBP worldwide [1]. LBP bears both neuropathic and nociceptive components which complicate its management [2]; several guidelines and treatment strategies have been proposed for management [3,4]. Potent pain relievers including opioids have been used to alleviate LBP; however, evidence on their effectiveness remains scarce [5,6]. Tapentadol, a dual-mechanism opioid, acts as a μ-opioid receptor agonist and a norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor. This synergistic activity increases its potency as an analgesic that acts centrally to attenuate pain, with salient features such as efficacy comparable to other opioid analgesics, favorable efficacy/side-effect ratio, and reduction in adverse effects typically associated with classical opioids [7]. Tapentadol was found to effectively relieve moderate-to-severe chronic LBP with better gastrointestinal tolerability than oxycodone HCl CR [8] and with higher efficacy than tramadol [9]. It was associated with improvements in pain intensity and quality-of-life measures in a phase 3b study by Baron et al. [10] and resulted in long-term pain relief [11] in patients with chronic LBP. Results from observational/retrospective studies [12-15] are also in concordance with data from these interventional trials. Despite the advantages of oral tapentadol, it has limitations including low bioavailability, low lipid solubility, lack of analgesic effects of the majority of its metabolites, relatively slow absorption that is inadequate for management of breakthrough pain, gastrointestinal adverse effects, and low patient adherence due to a less-acceptable taste. Intranasal administration using an alternate formulation facilitates rapid absorption and fast onset of action and has been reported to enhance efficacy [16]. Intranasal drug delivery is a safe and effective alternative to oral, intravenous (IV), and intramuscular modes of medication administration. The procedure is technically simple and non-invasive, thus reducing patient suffering. It has quick absorption and rapid onset, thus avoiding delays in pain management and often, reduced side effects due to a more targeted delivery. Rapid absorption is primarily due to the rich vasculature in the submucosa of nasal cavity, and rapid action is because this route targets the central nervous system, which is especially crucial for intranasal analgesics. This mode of administration also bypasses the metabolic first-pass effect which, in turn, increases peak plasma concentrations and bioavailability. However, there is limited evidence on the effectiveness of intranasal analgesics for LBP [17-20]. Tapentadol nasal spray (NS) was found to be more effective compared to IV tramadol [16] and intramuscular diclofenac [21] in postoperative patients and compared to diclofenac tablet in patients after tooth extraction [22]. To the best of our knowledge, there is no reported evidence for the effectiveness and tolerability of tapentadol NS in LBP of patients with LBP treated using Tapentadol NS.

Study design

This investigator-initiated, retrospective, real-world, observational study was conducted at the Department of Orthopedics of a single study site using data from EMRs of patients treated with tapentadol NS for management of LBP between February 2021 and August 2022. The EMRs contained patient-reported pain and sleep assessment, as recorded on the 11-point numeric pain rating scale (NPRS; 0: no pain; 10: worst pain imaginable) and global sleep quality scale (0: no sleep difficulty; 1: mild sleep difficulty; and 2: moderate sleep difficulty), respectively. Data were retrieved from EMRs for multiple time points on 3 consecutive days after baseline (day 0).

Ethical considerations

This study was conducted according to the “National Ethical Guidelines for Biomedical and Health Research involving Human Participants, ICMR, 2017” and initiated after obtaining written approval from the Institutional Ethics Committee for Biomedical and Health Research (IECBH) of the study site. The patients were identified using system-generated unique IDs, thus ensuring confidentiality. The trial was registered with the Clinical Trials Registry-India (CTRI) on May 14, 2024 (reference number: CTRI/2024/05/067264).

Study objectives and study endpoints

The current study aimed to assess the effectiveness and tolerability of tapentadol NS in LBP. Toward this, the primary endpoint was a change in pain severity based on NPRS. The secondary endpoints were the proportion of patients requiring rescue medicine (IV or IV paracetamol), change in the global sleep quality score, and incidence of adverse events (AEs; nausea, vomiting, dizziness, and allergic reactions post-medication).

Sample size

An observational study using tapentadol NS for the management of postoperative pain showed an 84.28% improvement in postoperative pain at the end of 72 h in patients [16]. Based on these results, a total of 300 patients was computed for the current study to observe similar improvement with 95% confidence interval (CI) and ~4% margin of error, considering 5% missing data.

Eligibility criteria

Data from 18 to 65-year-old patients were included in the study only if all the following criteria were satisfied: Patients with a medical history and physical and neurological examinations that supported a clinical diagnosis of acute/chronic LBP felt down to the lower leg below the knee, patients with data available on pain and sleep scores, patients with a minimum pain score of 4 on NPRS, and patients who were medically stable on the basis of physical examination, medical history, vital signs, and clinical laboratory tests performed prior to commencement of tapentadol NS administration. The following were the exclusion criteria of the study: History of hypersensitivity to tapentadol, active or suspected gastrointestinal ulcers, bleeding, or motility disorders within 6 months and recent intranasal medication within 72 h preceding commencement of tapentadol NS administration, concurrent use of tricyclic antidepressants, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, selective noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors, anticonvulsants, neuroleptics, triptans, steroids, monoamine oxidase inhibitors, or drugs with potential to lower seizure threshold within 4 weeks before tapentadol NS administration, history of seizures, mild-to-moderate traumatic brain injury, stroke, or brain neoplasm within 1 year or severe traumatic brain injury within 15 days before tapentadol NS administration, or clinically significant electrocardiogram abnormalities.

Statistical methods

All statistical methods were based on the International Council for Harmonization E9 document “Statistical Principles for Clinical Trials” and performed using IBM Statistical Packages for the Social Sciences 29.0.2.0. The null hypothesis of the study was that tapentadol NS administration has no effect in the management of pain (P > 0.05), whereas the alternate hypothesis was that tapentadol NS administration has an effect in pain management (P < 0.05). Quantitative data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD), median, minimum and maximum, standard error of the mean, standard error, and 95% CI, as appropriate. Categorical variables were reported as proportion/percentage. Scores on NPRS were analyzed using one-way or repeated measures analysis of variance with post hoc (Bonferroni correction); P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

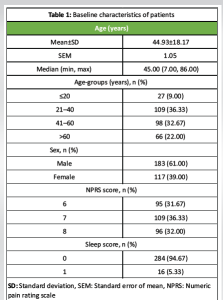

Baseline characteristics of patients

Data from a total of 300 patients was included for analysis. As per the EMRs, tapentadol NS was administered at a dose of 22.5 mg per spray in each nostril (45 mg/dose) every 4–6 h for a period of 3 consecutive days. Among the patients, 183/300 (61.00%) were male and 117/300 (39.00%) were female. The mean ± SD age of patients was 44.93 ± 18.17 years and the median age was 45 years; the mode value of age was 60 years. The majority (36.33%) of the patients were between 21 and 40 years old. The pain score at baseline (on NPRS) ranged between 6 and 8, with most patients (36.33%) having a score of 7. Most patients (94.67%) did not have sleep difficulty at baseline (Table 1). Lumbar canal stenosis was the most commonly-detected cause of LBP, being diagnosed in 85 (28.3%) patients.

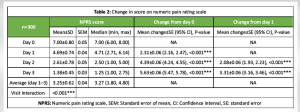

Change in pain score

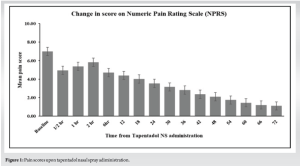

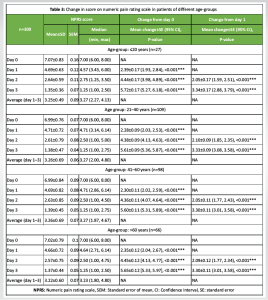

The mean ± SD pain score reduced from 7.00 ± 0.80 on day 0 to 4.69 ± 0.74 on day 1, 2.61 ± 0.78 on day 2, and 1.38 ± 0.45 on day 3; all changes from day 0 or day 1 to subsequent days were statistically significant (P < 0.001 for all). Thus, tapentadol NS administration reduced above-moderate pain to below-moderate levels at as early as 2 days post-treatment initiation. The pain score at day 3 ranged between 1 and 2.75 (Table 2). Pain intensity decreased by 80.29% from day 0 to day 3. Except for three patients, the rest (99.00%) had >51% reduction in pain. The recorded pain scores are given in Fig. 1.

Analysis of patients from different age groups showed that pain intensity or NPRS score reduced significantly from day 0 or day 1 to subsequent days in all age-groups (P < 0.001 for all). The percentage of reduction in pain intensity was comparable among the age-groups (≤20 years: 80.91%; 21–40 years: 80.26%; 41–60 years: 80.11%; >60 years: 80.48%) (Table 3).

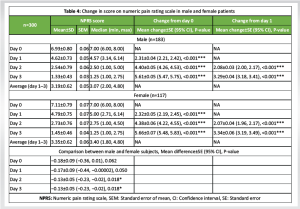

Both male and female patients showed significant reduction in pain intensity or NPRS score from day 0 or day 1 to subsequent days (P < 0.001 for all) (Table 4). From day 0 to day 3, pain intensity was reduced by 80.81% in male patients and 79.61% in female patients.

Requirement of rescue medicine

Rescue medication (IV paracetamol) was required in only 5/300 (1.67%) patients on day 1 of whom 4/300 (1.33%) patients continued the same on day 2. By day 3, none of the patients required rescue medication.

Change in global sleep quality score

Mild sleep difficulty (score = 1) was reported by 16 (5.33%) patients on day 1 which resolved on subsequent days. Overall, there was a significant improvement in sleep quality from a mean score of 0.05 on day 1 to “no sleep difficulty” (score = 0) on subsequent days (P < 0.001 for all).

Incidence of AEs

No AEs were reported.

LBP is a debilitating condition that impairs daily activities and diminishes the quality of life. A treatment modality that provides quick relief to patients with minimal side effects is the need of the hour in current times with ever-increasing incidence of the condition not only in the elderly but also in young adults. Most patients (36.33%) in the current study were in the age group of 21–40 years. Tapentadol is known to be a potent analgesic. It was reported to be advantageous over other analgesics in terms of pain control and less need for reassessments [13]. Analysis of real-world data proved the effectiveness and tolerability of tapentadol in patients with considerable pain despite treatment with less potent pain medications [14]. However, its oral mode of administration has drawbacks such as slow onset of action, gastrointestinal adverse effects, and lower patient tolerability/adherence. For instance, multiple AEs were reported in a study that proved long-term pain relief with reduced segmental sensitization using oral tapentadol [11] as well as in a randomized study that showed improvements in pain intensity and quality of life upon tapentadol administration [10]. Gastrointestinal tolerability of oral tapentadol was found to be better than oxycodone HCl CR with effective pain relief [8,23]; however, 43.7% of patients reported gastrointestinal AEs in a randomized controlled trial by Buynak et al. [8] Taken together, evidence from the literature suggests that oral tapentadol is effective in the alleviation of LBP, but it has considerable side effects. Administering tapentadol intranasally overcomes these limitations and therefore, provides an alternative option to physicians toward patient care. Tapentadol NS thus combines the effectiveness of tapentadol with additional benefits of quick onset of action and reduced gastrointestinal AEs [16], advantages that are concordant with the intranasal route of medication administration [17-20]. In the current study, Tapentadol NS was found to be effective in attenuating LBP in both male and female patients and in patients from all groups (18–65 years). An overall reduction of pain intensity by 80.29% was achieved after 3 days of tapentadol NS administration; the percentage of reduction was >80% in all age groups. There was a significant improvement in sleep quality with no reported AEs during the 3 days of treatment. Most patients (98.33%) did not require any rescue medications. Findings from LBP patients in this study are concordant with those reported in postoperative patients in an earlier observational study wherein a decrease in pain intensity by 84.29% was observed after 72 h with significant improvement in sleep quality, minimal requirement of rescue medication, and no reported AEs [16]. Another study in post-operative patients also reported significant pain relief using tapentadol NS [21]; similar observations were made in a randomized controlled trial wherein patients treated with tapentadol NS did not experience any pain after tooth extraction and did not require rescue analgesics [22]. Earlier studies reported the efficacy of oral tapentadol in LBP. For instance, a 50% pain relief was achieved in 66% of patients <65 years of age after 4 months of treatment [12]. A recent study reported 50% pain reduction after 4 weeks of treatment with oral tapentadol; AEs included nausea, dizziness, and constipation [9]. In comparison, >51% pain reduction was noted in 99% of patients in the current study with no reported AEs during tapentadol NS treatment for 3 days. Overall, this study proves the effectiveness and tolerability of tapentadol NS and adds worthy evidence to support its use in LBP in addition to pain associated with surgery and tooth extraction as reported by earlier researchers [16,21,22]. However, this study is limited by the 3-day duration of follow-up and the lack of a comparator in the analysis. The dependence of conclusions on patient-reported outcomes and the fact that this is a retrospective study might also introduce bias. A longitudinal study for a longer period of follow-up would be useful to investigate symptom recurrence after completion of treatment and to assess whether further interventions are required; such a study would also inform on AEs, if any. Long-term pain relief using oral tapentadol has been reported earlier [11,23]; similar studies are required to be performed using tapentadol NS in order to strengthen the basis for advocating this relatively newer mode of administration of the analgesic. It should be remembered that not all patients might be compatible with intranasal administration of medication; for instance, patients with significant compromise of nasal passages, mucosa, or airway cannot undergo intranasal treatment [17].

Tapentadol NS was found to be effective and well-tolerated in adult male and female patients of different age groups diagnosed with LBP; pain alleviation was noted as concomitant with improvement in sleep quality and absence of side effects. Intranasal administration offers rapid absorption and minimal side effects. Pain reduction was significant, with >99% of patients experiencing >51% relief. No AEs were reported, making it a safe alternative to oral opioids. More extensive trials are needed to confirm long-term effectiveness.

The findings of this study suggest that tapentadol NS is an effective and well-tolerated option for the rapid relief of LBP. Its ability to provide significant pain reduction and improve sleep quality highlights its potential as a valuable treatment alternative, particularly for patients requiring fast-acting analgesia. Clinicians should consider tapentadol NS as part of a comprehensive pain management strategy, ensuring appropriate patient selection and monitoring for optimal outcomes.

References

- 1.World Health Organization (WHO). WHO Releases Guidelines on Chronic Low Back Pain. World Health Organization; 2023. Available from: https://www.who.int/news/item/07-12-2023-who-releases-guidelines-on-chronic-low-back-pain [Last accessed on 2024 May 29]. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 2.Coluzzi F, Polati E, Freo U, Grilli M. Tapentadol: An effective option for the treatment of back pain. J Pain Res 2019;12:1521-8. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 3.Buchbinder R, Van Tulder M, Öberg B, Costa LM, Woolf A, Schoene M, et al. Low back pain: A call for action. Lancet 2018;391:2384-8. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 4.Baron R, Binder A, Attal N, Casale R, Dickenson AH, Treede RD. Neuropathic low back pain in clinical practice. Eur J Pain 2016;20:861-73. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 5.Drewes AM, Jensen RD, Nielsen LM, Droney J, Christrup LL, Arendt-Nielsen L, et al. Differences between Opioids: Pharmacological, experimental, clinical and economical perspectives. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2013;75:60-78. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 6.Busse JW, Craigie S, Juurlink DN, Buckley DN, Wang L, Couban RJ, et al. Guideline for opioid therapy and chronic noncancer pain. CMAJ 2017;189:E659-66. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 7.Alshehri FS. Tapentadol: A review of experimental pharmacology studies, clinical trials, and recent findings. Drug Des Devel Ther 2023;17:851-61. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 8.Buynak R, Shapiro DY, Okamoto A, Hove IV, Rauschkolb C, Steup A, et al. Efficacy and safety of tapentadol extended release for the management of chronic low back pain: Results of a prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo- and active-controlled Phase III study. Expert Opin Pharmacother 2010;11:1787-804. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 9.Gul N, Ramooz K, Shehzad Y, Gondal SS, Mehmood F, Ali Khan HM, et al. The lower-back painkiller challenge: Efficacy of tramadol versus tapentadol. Pak J Neurol Surg 2023;27:156-63. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 10.Baron R, Martin-Mola E, Müller M, Dubois C, Falke D, Steigerwald I. Effectiveness and safety of tapentadol prolonged release (PR) versus a combination of tapentadol pr and pregabalin for the management of severe, chronic low back pain with a neuropathic component: A randomized, double-blind, phase 3b study. Pain Pract 2015;15:455-70. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 11.Van De Donk T, Van Cosburgh J, Van Dasselaar T, Van Velzen M, Drewes AM, Dahan A, et al. Tapentadol treatment results in long-term pain relief in patients with chronic low back pain and associates with reduced segmental sensitization. Pain Rep 2020;5:e877. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 12.Freo U, Furnari M, Ambrosio F, Navalesi P. Efficacy and tolerability of tapentadol for the treatment of chronic low back pain in elderly patients. Aging Clin Exp Res 2021;33:973-82. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 13.Guillén-Astete CA, Cardona-Carballo C, De La Casa-Resino C. Tapentadol versus tramadol in the management of low back pain in the emergency department: Impact of use on the need for reassessments. Medicine (Baltimore) 2017;96:e8403. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 14.Überall MA, Elling C, Eibl C, Müller-Schwefe GH, Lefeber C, Heine M, et al. Tapentadol prolonged release in patients with chronic low back pain: Real-world data from the German pain eregistry. Pain Manag 2022;12:211-27. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 15.Bagaphou TC, Cerotto V, Gori F. Efficacy of tapentadol prolonged release for pre- and post-operative low back pain: A prospective observational study. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 2019;23:14-20. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 16.Sunil S, Sachin K, Shikhar S, Shobhan M, Vidur S, Varmit S, et al. Head-to-head comparison of tapentadol nasal spray and intravenous tramadol for managing postoperative moderate-to-severe pain: An observational study. Indian J Pain 2023;37:S41-4. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 17.Bailey AM, Baum RA, Horn K, Lewis T, Morizio K, Schultz A, et al. Review of intranasally administered medications for use in the emergency department. J Emerg Med 2017;53:38-48. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 18.Wewege MA, Bagg MK, Jones MD, Ferraro MC, Cashin AG, Rizzo RR, et al. Comparative effectiveness and safety of analgesic medicines for adults with acute non-specific low back pain: Systematic review and network meta-analysis. BMJ 2023;380:e072962. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 19.Keller LA, Merkel O, Popp A. Intranasal drug delivery: Opportunities and toxicologic challenges during drug development. Drug Deliv Transl Res 2022;12:735-57. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 20.Zanza C, Saglietti F, Giamello JD, Savioli G, Biancone DM, Balzanelli MG, et al. Effectiveness of intranasal analgesia in the emergency department. Medicina (Kaunas) 2023;59:1746. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 21.Singh S, Sawal R, Singh A. A comparative study of a tapentadol nasal spray and intramuscular diclofenac sodium in the post-operative pain management. J Cardiovasc Dis Res 2023;14:426-30. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 22.Mazhari KH, Chandra J, Sequeira JP. Tapentadol nasal spray is an effective way of pain management after tooth extraction: A randomized control clinical trial. J Pharm Res Int 2023;35:9-14. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 23.Afilalo M, Morlion B. Efficacy of tapentadol ER for managing moderate to severe chronic pain. Pain Physician 2013;16:27-40. [Google Scholar | PubMed]