True orthopaedic wisdom lies in choosing what’s best for the patient, not what’s most invasive, as many musculoskeletal conditions can be effectively managed without surgery. One must consider the available infrastructure, the patient’s profile, comorbidities, and the surgeon’s own capabilities before deciding on surgical management.

Dr. Janki Sharan Bhadani, Department of Orthopaedics, Paras HMRI Hospital, OPD No.4, Patna- 800014, Bihar, India. E-mail: jsbhadani@gmail.com

There is a famous saying that, “A good surgeon knows how to operate, a better one when to operate, and the best when not to” [1]. In orthopedics, we’re often trained to fix things. Yet, some of the wisest decisions are those that withhold its use. The courage not to cut is not indecision or doing less – it’s about doing what’s right. It’s about stepping back, when surgery might do more harm than good [2]. Modern orthopedics is replete with advanced imaging, implants, and surgical techniques. These tools must serve – not dictate – clinical judgment. The temptation to operate, especially when equipped with cutting-edge implants and techniques, must be tempered by the surgeon’s responsibility to do no harm.

Surgery is never without consequences and in frail, elderly, or medically compromised patients, even minor procedures can lead to major setbacks. In such individuals, surgery can trigger a cascade of complications – from infections and implant failure to delirium and death. In such cases, choosing not to operate is about protecting quality of life and respecting the delicate balance of a patient’s overall health [3].

Modern medicine is about working with the patient. Some patients may choose not to go through with a surgery after understanding all the risks, outcomes, and what recovery would look like. Listening to their concerns, values, and life goals is part of good care. Shared decision-making transforms passive consent into active partnership. We must listen to our patients’ goals [4]. Does the elderly woman with a hip fracture want to walk again or just live without pain? Does the young athlete prioritize speed or long-term joint health? Saying “no” to surgery can be the most powerful yes to what matters most to them – whether that’s independence, comfort, or time with loved ones. In these moments, respecting their choice is ethical and deeply humane. Communication Before Incision Central to non-operative care is communication. The patient who is told “nothing can be done” often walks away dejected. However, when we explain that healing can happen without surgery – and outline the plan, the rationale, and the expected timeline – hope is rekindled [5].

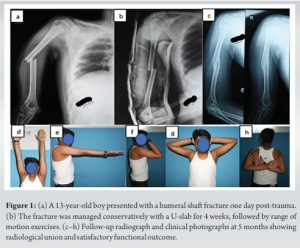

It acknowledges that success in orthopedics is not measured solely by X-rays and incisions, but by lives lived well. The philosophy of non-operative care requires us to trust biology, understand biomechanics, and honor the patient’s narrative [6]. Non-operative orthopedics encompasses a spectrum of strategies that aim to manage musculoskeletal conditions without surgical intervention. Treatments, such as physiotherapy, medications, cast, braces, orthotics, injections, and lifestyle changes are often safer and effective, especially for those who may not tolerate surgery well. With proper guidance and follow-up, many conditions heal well without an operation. In some cases, such as clavicle fractures, humeral shaft fracture, certain spinal fractures, or rotator cuff tears non-surgical treatment can offer outcomes similar to surgery when carefully selected [7,8]. (Fig. 1).

This philosophy aligns with the principle of primum non nocere – first, do no harm – and reinforces the surgeon’s role not just as a technician, but as a thoughtful healer [9]. The significance of this approach becomes even more evident in the following clinical scenarios:

1.Pediatric Fractures: Letting Nature Lead the Way

Child heals in ways that adults simply don’t. Their bones are growing, flexible, and capable of remarkable self-repair. With the right guidance, many childhood fractures just need time, support, and smart follow-up. A shift toward non-operative protocols is emerging, promoting healing with minimal intervention, especially in conditions, such as infant DDH, where structured, non-surgical treatment yields consistently positive results [10].

2.Knee Osteoarthritis: Relief Without the Knife

For knee osteoarthritis, surgery can feel like the only option, but that’s not always true. Many patients can regain mobility and reduce pain through early, consistent non-operative care. Evidence supports a combination of NSAIDs, weight loss, intra-articular injections, bracing, managing obesity, and improving muscle strength can significantly ease symptoms. With a personalized, multidisciplinary approach, patients can experience real improvement, often without ever going under the knife. Early intervention is key to maximizing function and delaying or avoiding surgery altogether [11].

3.Low Back Pain: The Hidden Power of Conservative Care

Back pain is one of the most common complaints in clinics. It’s also one of the most overtreated with surgery. Experts have long said that physical therapy, posture correction, strengthening exercises, and lifestyle changes can offer better results than surgery in many cases. Surgery for back pain should be the last resort – not the first step. Conservative care is powerful if given the time and attention it deserves [12].

The COVID-19 pandemic reminded us of this. Sometimes, simpler treatments are not only enough – they’re better, safer, and more efficient. A 2020 report showed that during the crisis, non-operative treatments were used more often, and outcomes remained acceptable (Dabas et al., 2020) [13].

Perhaps the greatest disservice to young surgeons is teaching them that doing something is always better than doing nothing [14]. We must train our residents not only in surgical techniques but also in the art of clinical decision-making, including when not to operate. The “treatment trap” refers to situations where the very availability of an intervention becomes its justification [15]. For example, the minimally displaced distal radius fracture in a sedentary octogenarian, plated with precision, but with marginal gains. Such decisions carry real costs including surgical risks, longer recovery times, psychological burden, and unnecessary resource utilization. Thus, clinical acumen, patient communication, and ethical discernment must be emphasized alongside anatomy and biomechanics in our educational frameworks. We must celebrate non-operative success stories as much as complex surgical triumphs. The art of medicine lies in choosing the right treatment, not the most dramatic one.

Evidence supports the value of non-operative management in several common fractures:

- The AAOS guidelines suggest that outcomes for non-operative and operative treatment of distal radius fractures in elderly are similar after 1 year [16].

- The PROFHER trial has shown that in selected patients, particularly where the surgeon is uncertain about the clear need for surgery, nonoperative management of proximal humerus fractures yields outcomes comparable to surgical treatment at 2-year follow-up [17].

- The adage, often attributed to Sarmiento, humorously but insightfully suggests that a humeral shaft fracture will heal even if the two ends are placed at opposite corners of a room provided no one disturbs it with surgery [18].

These days, with all the high-tech tools and fancy procedures, it’s easy to think that doing more always means better care. However, sometimes, the best thing we can do is simply wait, offer support, and let the body heal on its own. Choosing not to operate isn’t doing nothing, it’s a careful, thoughtful decision. In a world where surgery often gets the spotlight, stepping back can actually show true wisdom. It means we’re looking at the whole person, not just the X-ray. We care more about real recovery than just doing something for the sake of it. Sometimes, the smartest and kindest thing a surgeon can do is… nothing.

References

- 1.Luscan R, Malheiro E, Sisso F, Wartelle S, Parc Y, Fauroux B, et al. What defines a great surgeon? A survey study confronting perspectives. Front Med (Lausanne) 2023; 10:1210915. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 2.Reider B. To cut … or not? Am J Sports Med 2015; 43:2365-7. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 3.Sudlow A, Tuffaha H, Stearns AT, Shaikh IA. Outcomes of surgery in patients aged ≥90 years in the general surgical setting. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2018; 100:172-7. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 4.Páez G, Forte DN, Gabeiras MD. Exploring the relationship between shared decision-making, patient-centered medicine, and evidence-based medicine. Linacre Q 2021; 88:272-80. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 5.Al Ghunimat A, Hind J, Abouelela A, Sidhu GA, Lacon A, Ashwood N. Communication with patients before an operation: Their preferences on method of communication. Cureus 2020;12: e11431. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 6.Watson A, Leroux T, Ogilvie-Harris D, Nousiainen M, Ferguson PC, Murnahan L, et al. Entrustable professional activities in orthopaedics. JB JS Open Access 2021;6: e20.00010. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 7.Boorman RS, More KD, Hollinshead RM, Wiley JP, Mohtadi NG, Lo IK, et al. What happens to patients when we do not repair their cuff tears? Five-year rotator cuff quality-of-life index outcomes following nonoperative treatment of patients with full-thickness rotator cuff tears. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2018; 27:444-8. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 8.Waldmann S, Benninger E, Meier C. Nonoperative treatment of midshaft clavicle fractures in adults. Open Orthop J 2018; 12:1-6. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 9.Smith CM. Origin and uses of primum non nocere--above all, do no harm! J Clin Pharmacol 2005; 45:371-7. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 10.Bradley CS, Verma Y, Maddock CL, Wedge JH, Gargan MF, Kelley SP. A comprehensive nonoperative treatment protocol for developmental dysplasia of the hip in infants: A prospective longitudinal cohort study. Bone Joint J 2023;105-B:935-42. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 11.Ferreira RM, Martins PN, Gonçalves RS. Non-pharmacological and non-surgical interventions to manage patients with knee osteoarthritis: An umbrella review 5-year update. Osteoarthr Cartil Open 2024; 6:100497. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 12.Giraldo JP, Williams GP, Lee JJ, Potts EA, Uribe JS. An evidence-based review of the current surgical treatments for chronic low-back pain: Rationale, indications, and novel therapies. J Neurosurg Spine 2025; 42:413-24. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 13.Phillips MR, Chang Y, Zura RD, Mehta S, Giannoudis PV, Nolte PA, et al. Impact of COVID-19 on orthopaedic care: A call for nonoperative management. Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis 2020; 12:1759720X20934276. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 14.Stefanescu MC, Sterz J, Hoefer SH, Ruesseler M. Young surgeons’ challenges at the start of their clinical residency: A semi-qualitative study. Innov Surg Sci 2018; 3:235-43. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 15.Meier DE. Book review: ‘The treatment trap: How the overuse of medical care is wrecking your health and what you can do to prevent it” by rosemary Gibson and Janardan Prasad Singh. Oncol Times 2010; 32:56. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 16.Kamal RN, Shapiro LM. American academy of orthopaedic surgeons/American society for surgery of the hand clinical practice guideline summary management of distal radius fractures. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2022;30: e480-6. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 17.Rangan A, Handoll H, Brealey S, Jefferson L, Keding A, Martin BC, et al. Surgical vs nonsurgical treatment of adults with displaced fractures of the proximal humerus: The PROFHER randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2015; 313:1037-47. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 18.Sarmiento A, Kinman PB, Galvin EG, Schmitt RH, Phillips JG. Functional bracing of fractures of the shaft of the humerus. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1977; 59:596-601. [Google Scholar | PubMed]