Pediatric hip deformities can rarely present with an unknown etiology. Stability of the fracture site should be chosen over preserving bone growth. Restoration of the Hilgenreiner epiphyseal angle is critical to prevent recurrence of coxa vara.

Dr. J K Giriraj Harshavardhan, Department of Orthopedic Surgery, Sri Ramachandra Institute of Higher Education and Research, Chennai - 600 116, Tamil Nadu, India. E-mail: girirajh@yahoo.com

Background: Coxa vara is a rare pediatric hip disorder characterized by a reduced femoral neck shaft angle (NSA) (<120°), resulting in limb length discrepancy, gait abnormalities, and hip dysfunction. While developmental coxa vara has characteristic radiological features, atypical presentations with unknown etiologies are infrequently reported.

Case Report: A 7-year-old boy with left hip pain presented without any history of trauma or systemic illness. Radiographs and computed tomography imaging revealed coxa vara with a transcervical femoral neck fracture with a mixed predominantly sclerotic lesion in the femoral neck. A closed-wedge valgus osteotomy was performed with internal fixation using a locking plate and screws placed proximal to the physis. Intraoperative biopsy ruled out tumor or infection. Although initial outcomes were favorable, recurrence of coxa vara and femoral neck fracture occurred after 1 year and 9 months. Revision surgery involved medial open-wedge osteotomy with bone grafting and fixation using a pediatric dynamic hip screw, with the lag screw crossing the physis for stability. At the 8th-year follow-up, the patient was pain-free, with minimal limb shortening and good functional mobility. X-rays showed solid radiographic union, disappearance of the previously noted sclerotic lesion in the left femoral neck, and maintenance of the NSA.

Discussion: This case involves coxa vara with atypical radiographic features, complicating its classification as developmental or acquired. Initial fixation that preserved the physis resulted in recurrence. Subsequent fixation crossing the physis, along with correction of the Hilgenreiner epiphyseal (HE) angle, effectively prevented recurrence. At 8-year follow-up, the patient demonstrated a good clinical and radiological outcome.

Conclusion: The HE angle is a critical prognostic factor in predicting the recurrence of coxa vara. Surgical stability should take precedence over physeal preservation.

Keywords: Coxa vara, Hilgenreiner epiphyseal angle, neck shaft angle.

Coxa vara is a rare pediatric condition characterized by a pathological reduction in the femoral neck shaft angle (NSA) (<120°), leading to hip dysfunction and limb shortening [1]. Developmental coxa vara (DCV) typically presents with characteristic radiographic features, and atypical presentations have not been well documented in the literature. Acquired coxa vara can result from trauma, infection, or bone lesions. We present a rare case of unilateral coxa vara in a child with an unusual mixed sclerotic lesion in the femoral neck. Surgical correction was undertaken with good functional and radiological outcomes.

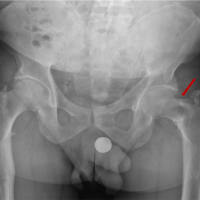

A 7-year-old boy presented with left hip pain for 1 year without any history of trauma or systemic illness. Antenatal and birth history were uneventful. Developmental history was normal. Movements of the left hip were restricted (especially internal rotation), with the left femur shortened by 2 cm. The Trendelenburg test was negative. Initial X-ray and computed tomography (CT) showed a left neck of femur transcervical fracture with a mixed area of lucency and sclerosis (predominant) in the femoral neck (Fig. 1).

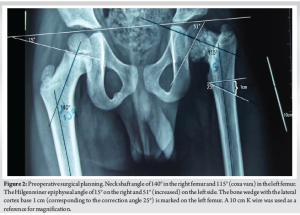

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed signal intensity changes in the left femoral neck. NSA of the left femur was 115°, with Hilgenreiner epiphyseal (HE) angle of 51° (Fig. 2), and hence, surgical correction was required [1,2,3,4].

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed signal intensity changes in the left femoral neck. NSA of the left femur was 115°, with Hilgenreiner epiphyseal (HE) angle of 51° (Fig. 2), and hence, surgical correction was required [1,2,3,4].

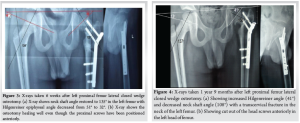

On August 22, 2013, the patient underwent surgery: Left proximal femur lateral closed-wedge osteotomy. A wedge with a 1 cm base was removed at the corticotomy site, corresponding to a correction angle of 25° based on templating with a magnification marker (Fig. 2 – a K-wire of known length was used as a magnification marker). Closed biopsy was taken from the neck of the femur. Two cannulated cancellous screws were passed through the neck (not crossing the physis) and locked to the prebent 3.5 mm six-holed dynamic compression plate. Since the proximal femoral physis contributes to around 15% of the overall growth of the femur, the screws were fixed without crossing the physis [5]. The plate was fixed to the shaft with three cortical screws. Post-operatively, the NSA and HE angle were restored (Fig. 3).

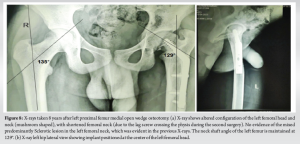

Post-operatively, the patient was mobilized after 6 weeks. Intraoperative biopsy ruled out any tumor/infective foci in the left femoral neck region. The osteotomy healed well. However, 1 year and 9 months after the initial surgery, the patient experienced a recurrence of pain in the left hip and limp. Radiograph showed recurrence of left coxa vara (Fig. 4) with a trans cervical fracture in the neck of the left femur. Probably the tip of the screws inserted into the neck was acting as stress risers. The patient underwent left femur implant removal + medial open wedge osteotomy with bone grafting from the left tibia + internal fixation with pediatric dynamic hip screw (DHS) on May 21, 2015. During the surgery, the lag screw (45 mm) was placed across the physis (stability was prioritized). Post-operatively, the NSA and HE angle were restored (Fig. 5).

Post-operatively, the patient was mobilized after 6 weeks of bed rest. The patient was regularly followed up on an outpatient basis, and serial X-rays demonstrated a maintained NSA (Fig. 6). On April 13, 2023 (8 years post-operative), the patient did not have any complaints of pain. Left hip movements were full, except internal rotation, which was restricted terminally. The left femur was shortened by 1 cm. The Trendelenburg test was negative. The patient mobilized, squatted, and moved his left hip pain-free (Fig. 7). Eight years post-operative X-ray (Fig. 8) showed left NSA in the acceptable range (129°) with shortening of the femoral neck. There was no evidence of the mixed, predominantly sclerotic lesion in the femoral neck, which was evident in the presenting X-ray.

Coxa vara refers to a pathological reduction in the NSA with an increase in femoral retroversion. Coxa vara can be secondary to trauma, infections, or metabolic disorders; associated with congenital femoral deficiency; or developmental (DCV), resulting from disruptions during the growth and maturation of the hip joint. This condition alters the biomechanics of the hip joint, resulting in limping, hip instability, pain, and limited mobility. With an estimated incidence of 1 in 25,000 live births, DCV is still a rather rare condition. Around 30–50% of patients have bilateral involvement [2]. Coxa vara is also associated with acetabular dysplasia [6]. The main controversy in the literature concerns the etiological classification of this condition. Broadly, the primary forms, with no other cause, are considered to be either congenital or developmental, while those with an obvious underlying cause are acquired [1]. Almond et al. established that infantile coxa vara is a familial condition [7]. Increased intrauterine pressure, localized dysplasia, metabolic abnormalities, vascular insult, and non-specific metabolic abnormality are a few hypothetical theories for primary coxa vara [1]. DCV is diagnosed with radiographs showing a decreased NSA (typically <120°), a vertical physis, a triangular metaphyseal fragment in the inferior femoral neck with an inverted “Y” shape, a shortened femoral neck (coxa breva), femoral retroversion, and often mild acetabular dysplasia [1,6]. The indications for surgical treatment of coxa vara are Hilgenreiner-epiphyseal angle >60° or HE angle 45–60° with progression of the deformity and Trendelenburg gait [1,2,3,4]. This case is an unusual presentation of DCV due to the absence of the classic triangular metaphyseal fragment in the inferior aspect of the femoral neck, which questions the very diagnosis of DCV. The pre-operative X-rays clearly demonstrated a mixed (predominantly sclerotic) lesion in the proximal femur metaphysis (femoral neck), which brings up the suspicion of a tumor or fibrous lesion. Pre-operative CT and MRI showed no evidence of metabolic bone diseases or a tumor. The presence of a pathological left neck of femur fracture warranted surgical fixation, and hence, left proximal femur lateral closed wedge osteotomy with proximal femur locking plate was done on August 22, 2013. Intraoperative biopsy sent for histopathological examination was inconclusive. The initial surgery was performed with screws that did not cross the proximal femoral physis, as this physis contributes approximately 15% to the overall growth of the femur [5]. However, the decision to preserve physeal growth led to recurrence of coxa vara due to inadequate stability (screws not crossing the physis) [8] and probably due to the stress riser effect of the tip of the screws inserted into the neck. In the second surgery, the lag screw of the DHS was placed across the physis, prioritizing mechanical stability over growth preservation. In addition, as the patient ages, the contribution of the proximal femoral physis to femoral growth decreases, while the distal femoral physis takes on a greater role, accounting for approximately 90% of femoral growth by 16 years of age [9]. Hence, the second procedure-medial open wedge osteotomy and fixation with pediatric DHS (with lag screw crossing the physis) corrected the deformity. Over a period of 8 years, the patient improved symptomatically, even though true shortening of the femur (1 cm) was present. HE angle is the most important prognostic factor for recurrence [2,3,4,10], and in this case, HE angle post-operatively was 32 and 36 degrees after the first and second procedure, respectively (which falls under the recommended reference value of 38° or less [3,11]). The NSA was also restored post-operatively in both procedures [12]. The X-ray taken 8 years post-DHS fixation (Fig. 8) showed shortening of the left femoral neck, which was due to the lag screw of the DHS crossing the physis. The X-ray (Fig. 8) clearly demonstrated the disappearance of the mixed (predominantly sclerotic) lesion in the proximal femur metaphysis, which was clearly evident in the presenting X-ray and CT. Yanagawa et al. (2001) identified several benign bone lesions with potential for spontaneous regression, including bony exostosis, non-ossifying fibroma, and osteoid osteoma [13].

However, the lesion in this case doesn’t fit the profile of any of these conditions. Osteofibrous dysplasia (OFD) is often expansile and lytic, commonly affecting the diaphysis. Similar to the lesion seen in the pre-op X-ray, OFD has a soap-bubble-like appearance, no matrix calcification, and has a history of spontaneous resolution during adolescence. However, no case of OFD has been recorded in the femoral neck or in any other metaphyseal region [14,15].

There are several known causes of acquired coxa vara documented in literature [1,16], but the findings in this case are inconsistent with established etiologies. This case may represent an atypical DCV or acquired coxa vara secondary to a benign self-resolving lesion. In case of any pathological lesion in the femoral neck requiring corrective surgery, it is prudent to cross the physis during fixation and obtain a stable fixation, as illustrated in our patient.

Preservation of physeal growth should not take precedence over the need for mechanical stability. A post-operative HE angle of ≤38° is critical for a good prognosis in coxa vara. Diagnostic ambiguity should not delay timely and decisive surgical intervention.

References

- 1.Key S, Ramachandran M. Congenital coxa vara. Paediatr Orthop Clin Pract 2016;3:125-33. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 2.Audisio A, Cacciola G, Braconi L, Giudice C, Massè A, Aprato A. Proximal femoral valgus osteotomy for the treatment of developmental coxa vara: A systematic review of the literature. J Orthop 2024;53:87-93. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 3.Cordes S, Dickens DR, Cole WG. Correction of coxa vara in childhood. The use of Pauwels’ Y-shaped osteotomy. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1991;73:3-6. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 4.Srisaarn T, Salang K, Klawson B, Vipulakorn K, Chalayon O, Eamsobhana P. Surgical correction of coxa vara: Evaluation of neck shaft angle, hilgenreiner-epiphyseal angle for indication of recurrence. J Clin Orthop Trauma 2019;10:593-8. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 5.Patterson JT, Tangtiphaiboontana J, Pandya NK. Management of pediatric femoral neck fracture. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2018;26:411-9. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 6.Ranade A, McCarthy JJ, Davidson RS. Acetabular changes in coxa vara. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2008;466:1688-91. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 7.Almond HG. Familial infantile coxa vara. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1956;38:539-44. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 8.Pandey RA, John B. Current controversies in management of fracture neck femur in children: A review. J Clin Orthop Trauma 2020;11:S799-806. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 9.Pritchett JW. Longitudinal growth and growth-plate activity in the lower extremity. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1992;275:274-9. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 10.Bian Z, Xu YJ, Guo Y, Fu G, Lyu XM, Wang QQ. Analyzing risk factors for recurrence of developmental coxa vara after surgery. J Child Orthop 2019;13:361-70. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 11.Sheppard E, Oetgen M. Proximal valgus femur osteotomy for coxa vara. J Pediatr Orthop Soc North Am 2020;2:170. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 12.Schlegl AT, Nyakas V, Kovacs D, Maroti P, Jozsa G, Than P. Neck-shaft angle measurement in children: Accuracy of the conventional radiography-based (2D) methods compared to 3D reconstructions. Sci Rep 2022;12:16494. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 13.Yanagawa T, Watanabe H, Shinozaki T, Ahmed AR, Shirakura K, Takagishi K. The natural history of disappearing bone tumors and tumor-like conditions. Clin Radiol 2001;56:877-86. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 14.Liu R, Tong L, Wu H, Guo Q, Xu L, Sun Z, et al. Osteofibrous dysplasia: A narrative review. J Orthop Surg Res 2024;19:204. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 15.Bethapudi S, Ritchie DA, Macduff E, Straiton J. Imaging in osteofibrous dysplasia, osteofibrous dysplasia-like adamantinoma, and classic adamantinoma. Clin Radiol 2014;69:200-8. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 16.Amstutz HC, Freiberger RH. Coxa vara in children. Clin Orthop 1962;22:73-92. [Google Scholar | PubMed]