Even minor trauma in a toddler can lead to the development of acute traumatic forearm compartment syndrome.

Dr. Yasushi Naganuma, Yamagata Prefectural Central Hospital, 1800 Aoyagi, Yamagata-Shi, Yamagata - 990-2292, Japan. E-mail: sun.green.moon@gmail.com

Introduction: Acute forearm compartment syndrome (AFCS) is rare in pediatric patients. Diagnosis of AFCS in pediatric patients is often difficult based on their presentation variability and immature verbal. We present a case of AFCS in a toddler who showed specific congestion from the distal forearm to the hand that resulted in a hematoma without fracture.

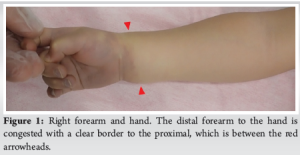

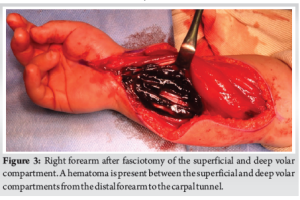

Case Report: A 2-year-old boy had right upper extremity pain and paralysis after falling from a chair. He had no family history of congenital hemorrhagic diseases or anticoagulant medications. His right distal forearm to hand was congested with a clear borderline to the proximal forearm. It was unable to detect any fractures in the X-rays. We diagnosed him with AFCS and performed a fasciotomy that showed a developing hematoma around the carpal tunnel. Two years after surgery, he had no signs of neurological defect in the upper extremity.

Conclusion: The toddler was injured by a low-energy fall, which was atypical enough to suggest the onset of ACFS. Congestion beyond the wrist, with a clear border to the proximal area, indicating peripheral circulatory disturbance, was the most notable physical finding in this case.

Keywords: Acute forearm compartment syndrome, pediatric trauma, trauma without fracture.

Acute forearm compartment syndrome (AFCS) is sporadic in pediatric patients but leads to severe disability of Volkmann’s contracture if it is diagnosed late or misdiagnosed [1]. Supracondylar humeral fracture is the most common cause of AFCS in pediatric patients [2], although trauma without fractures, endogenous or iatrogenic etiology, has also been reported [3-6]. However, the absence of fractures and the non-traumatic etiologies would make it difficult to suspect the onset of AFCS [5]. Furthermore, the diagnosis of AFCS in pediatric patients can be disturbing due to the variability of presentation and their immature verbal. AFCS in pediatric patients resulting from a hematoma developed around the carpal tunnel without fracture has not been previously described in the literature. We present a case of AFCS in a toddler who showed specific congestion at the injury site.

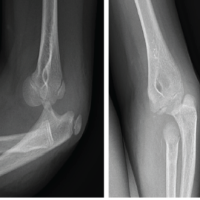

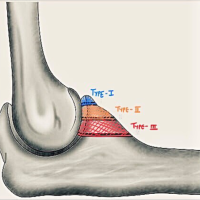

A 2-year-old boy was taken by his parents to the emergency department of our hospital 3 hours after falling from a chair. He had no family history of congenital hemorrhagic diseases nor anticoagulant medications. In his physical evaluation, he was crying and was found to be in right extremity pain with diffuse swelling and firming of the forearm. His right distal forearm to hand was congested with a clear border to the proximal forearm (Fig. 1), although the right radial pulse was palpable. He resisted attempting passive finger movement due to pain. It could not confirm his active finger movement, assess his sensory disturbance of the hand because his verbal ability was immature, nor detect any fractures in the X-rays of his right wrist, forearm, and elbow (Fig. 2). We found that the physical evaluations satisfied only two of the five P sign, which were pain and paralysis. Still, we diagnosed him with AFCS without fracture and immediately decided to perform a fasciotomy. According to his laboratory data, the platelet count was within the standard limit. However, neither bleeding time, prothrombin time, activated partial thromboplastin time, nor international normalized ratio was examined. Neither computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), Doppler ultrasonography, nor angiography was performed, as the shortening of time to surgery was chosen over the findings obtained from these tests. The intra-compartmental pressure of his right forearm was elevated over 80 mmHg under general anesthesia before surgery. Carpal tunnel release and extensile fasciotomy were performed in the dorsal, superficial volar, and deep volar compartments of his right forearm. A hematoma was found in the carpal tunnel of the distal forearm, and curettage was performed between the superficial and deep volar compartments (Fig. 3). Neither the radial nor ulnar arteries were occluded or blew actively. None of the vascular tumors around the carpal tunnel, vascular malformation of the arteries, or necrosis of the forearm muscles was observed. Following carpal tunnel release and fasciotomy, the tension of each compartment of the forearm was relieved, and the congestion of the hand improved immediately. Since primary closure was not possible due to soft-tissue swelling, the shoelace technique was used initially. Postoperatively, intravenous cefazolin sodium, 0.4 g every 12 h, was given for 48 h to prevent surgical site infection. For pain management, intravenous acetaminophen was given as needed. No occupational therapy was started during the postoperative period. On the 23rd postoperative day, an attempt was made to achieve partial primary closure. However, during suturing, high tension made it challenging to palpate the radial artery, potentially blocking blood flow. Consequently, the remaining areas were covered with split-thickness skin grafts. After surgery, to prevent scarring at the incision site, tension reduction with tape and topical application of heparinoid were continued for 6 months afterward. Two years after surgery, he had no signs of motor and sensory neurological defects in his right upper extremity. Given that he was only 4 years old, evaluating his upper limb function was not possible by patient-reported measures such as the Quick-Disabilities of the Arms, Shoulders and Hands. He also had a barely noticeable matured wound scar without hypertrophic scarring or skin contracture (Fig. 4). Moreover, he has never experienced episodes indicating potential hemorrhagic tendency or vascular disorders.

Acute compartment syndrome in pediatric patients associated with hematoma has previously been reported in hemorrhagic conditions, such as hemophilia [7] or during anticoagulant medication [5]. The development of a hematoma around the carpal tunnel could also be caused by the rupture of a vascular tumor, such as a hemangioma [8,9], or an intraneural venous malformation of the median nerve [10]. The risk factors for acute compartment syndrome in pediatric patients were analyzed in a meta-analysis; high-energy trauma was associated with a high risk, with an odds ratio of 3.51, whereas low-energy trauma was associated with a low risk, with an odds ratio of 0.31 [11]. In the present case, he had an average amount of platelets, although his coagulability was not examined. In addition, he had no family history of congenital disease or bleeding due to anticoagulant medication, such as hemophilia or von Willebrand disease. He was injured by a fall in a low place, which was an atypical low-energy trauma to suspect the onset of acute compartment syndrome. It is necessary to observe his progress after the surgery to prevent future adverse events because the latent hemorrhagic disease cannot be denied. Pediatric compartment syndrome can be challenging to diagnose. The five P signs, including pain, pallor, paresthesia, paralysis, and pulselessness, have been reported to have high specificity but low sensitivity [12]. Bae et al., have also suggested that 90% of pediatric patients with acute compartment syndrome had pain, but 75% had pain with one other symptom, and slightly 39% had pain with two or more symptoms, indicating that the five P signs could be a more advanced state of compartment syndrome [13]. Furthermore, Broom et al., have reported that the unique finding of compartment syndrome was the three A, which were agitation, anxiety, and an increasing number of analgesic requirements in children [6]. However, these signs are also nonspecific clinical findings, which could still be only an opportunity to suspect acute compartment syndrome. The accurate diagnosis of compartment syndrome is characterized by elevated intramuscular pressure; however, it is challenging to measure intra-compartmental pressure when a child is awake. Livingston et al., have suggested that measuring intra-compartmental pressure is essential in pediatric patients with atypical clinical findings that are difficult to diagnose as acute compartment syndrome [5]. In this case, due to the patient’s immature verbal skills, pain and motor function were indirectly evaluated through behavioral cues such as refusal to move. Furthermore, the patient had pain, paralysis, and congestion beyond the wrist, which was the most notable, indicating peripheral circulatory disturbance. Although only pain and paralysis were evident, these were sufficient in the context of pediatric presentation to suspect compartment syndrome. The patient was diagnosed with AFCS based on these physical findings, and fasciotomy was performed quickly, using intra-compartmental pressure measurement as a supplementary diagnosis. In addition, neither CT, MRI, Doppler ultrasonography, nor angiography was performed before the surgery. Although this imaging may have provided insight into the cause of the hematoma, the time-sensitive nature of compartment syndrome led us to prioritize prompt surgical intervention. The possibility of an underlying bleeding disorder or vascular anomaly could not be definitively excluded, as neither coagulation tests nor vascular imaging was performed. This remains a limitation of this case. Other differential diagnoses, such as cellulitis, venous thrombosis, and non-accidental injury, were considered; however, they were excluded based on clinical presentation and surgical findings. In the pathophysiology of compartment syndrome, tissue damage results from direct trauma, ischemia, and reperfusion [14]. In this case, the hematoma that developed around the wrist elevated the pressure in the carpal tunnel and occluded the peripheral capillaries. This led to hand ischemia and an increase in both internal pressure and capillary permeability in the forearm, which induced muscular edema and increased intramuscular pressure, resulting in AFCS.

We reported a case of a toddler injured by a low-height fall, which was too atypical a low-energy trauma to suspect the onset of ACFS. The developed hematoma around the carpal tunnel resulted in ACFS, although he was not under hemorrhagic conditions. Congestion beyond the wrist with a clear border to the proximal forearm, indicating peripheral circulatory disturbance, was the most prominent physical finding. This report focuses on a single patient and does not intend to make broad conclusions. Instead, it aims to raise awareness of the possibility of ACFS even in cases of unusual, low-impact pediatric trauma.

AFCS is rare and often difficult to diagnose in pediatric patients. Atypical etiology and physical presentations could cause AFCS. We report a case of AFCS in a toddler who showed specific congestion from the distal forearm to the hand, resulting in a hematoma without fracture.

References

- 1. Grottkau BE, Epps HR, Di Scala C. Compartment syndrome in children and adolescents. J Pediatr Surg 2005;40:678-82. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 2. Kalyani BS, Fisher BE, Roberts CS, Giannoudis PV. Compartment syndrome of the forearm: A systematic review. J Hand Surg Am 2011;36:535-43. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 3. Prasarn ML, Ouellette EA, Livingstone A, Giuffrida AY. Acute pediatric upper extremity compartment syndrome in the absence of fracture. J Pediatr Orthop 2009;29:263-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 4. Kanj WW, Gunderson MA, Carrigan RB, Sankar WN. Acute compartment syndrome of the upper extremity in children: Diagnosis, management, and outcomes. J Child Orthop 2013;7:225-33. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 5. Livingston K, Glotzbecker M, Miller PE, Hresko MT, Hedequist D, Shore BJ. Pediatric nonfracture acute compartment syndrome: A review of 39 cases. J Pediatr Orthop 2016;36:685-90. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 6. Broom A, Schur MD, Arkader A, Flynn J, Gornitzky A, Choi PD. Compartment syndrome in infants and toddlers. J Child Orthop 2016;10:453-60. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 7. Kim J, Zelken J, Sacks JM. Case report spontaneous forearm compartment syndrome in a boy with hemophilia A: A therapeutic dilemma. Eplasty 2013;13:e16. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 8. Meena D, Sharma M, Sharma CS, Patni P. Acute carpal tunnel syndrome due to a hemangioma of the median nerve. Indian J Orthop 2007;41:79-81. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 9. Doğramaci Y, Kalaci A, Sevinç TT, Yanat AN. Intraneural hemangioma of the median nerve: A case report. J Brachial Plex Peripher Nerve Inj 2008;3:5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 10. Porto SA, Rodríguez AG, Míguez JM. Intraneural venous malformations of the median nerve. Arch Plast Surg 2016;43:371-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 11. Mortensen SJ, Orman S, Testa EJ, Mohamadi A, Nazarian A, Von Keudell AG. Risk factors for developing acute compartment syndrome in the pediatric population: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol 2020;30:839-44. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 12. Ulmer T. The clinical diagnosis of compartment syndrome of the lower leg: Are clinical findings predictive of the disorder? J Orthop Trauma 2002;16:572-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 13. Bae DS, Kadiyala RK, Waters PM. Acute compartment syndrome in children: Contemporary diagnosis, treatment, and outcome. J Pediatr Orthop 2001;21:680-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 14. Von Keudell AG, Weaver MJ, Appleton PT, Bae DS, Dyer GS, Heng M, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of acute extremity compartment syndrome. Lancet 2015;386:1299-310. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]