Aneurysmal bone cyst of the talus is a rare lesion. A curettage and bone grafting yields excellent radiological and functional outcomes.

Dr. Segla Pascal Chigblo, Department of Orthopedic-Traumatology, National Teaching Hospital, CNHU-HKM, Cotonou, Benin. E-mail: chispaer@yahoo.fr

Introduction: Aneurysmal bone cyst (ABC) is a metaphyseal bone tumor that is frequent in children. Talar location is exceptional.

Case Report: We report a case of this rare lesion managed in our department. It was a 16-year-old girl who presented with heel pain at walk, without any trauma. Radiologic explorations found a pathologic fracture of the right talus due to a bone cyst. A surgical procedure was proceeded, with curettage, and bone grafting completed by a plastered immobilization. Histopathology confirmed the diagnosis of ABC. Consolidation was achieved in 2 months, and there was no recurrence after 5 years.

Conclusion: ABC of the talus is a rare etiology of heel pain, which must not be forgotten in children.

Keywords: Aneurysmal bone cyst, talus, pathological fracture, curettage, bone grafting.

Aneurysmal bone cyst (ABC) is a benign osteolytic lesion usually encountered in children and adolescents, described by Jaffe and Lichtenstein in 1942 [1,2]. It is predominantly located within the long bone’s metaphysis, spine, and pelvis [1,3]. Talus is an extremely rare site for ABCs [4], and there are several therapeutic options for this lesion. We report the first case managed by intralesional curettage and autologous bone grafting in our National Teaching Hospital, the level one hospital of a low-income country. Etiopathogeny, diagnostic, therapeutic, and evolutive aspects are discussed.

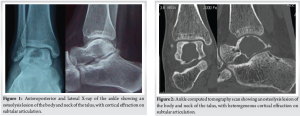

A 16-year-old girl student, from the Benin Republic, presented in our department with increasing right ankle pain. These pains began suddenly 4 months ago, without any trauma, and were maximal on walking. There was no fever, swelling, or weight loss. Personal and family histories were non-contributory. Physical examination was normal. Right ankle radiographs and computed tomography (CT) scan (Fig. 1 and 2) showed an osteolysis lesion type I a of Lodwick et al. [5], of the body and neck of the talus, with heterogeneous cortical effraction on the subtalar articulation.

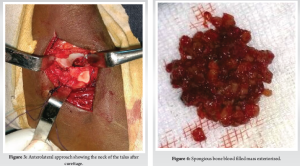

Based on these findings, a diagnosis of pathologic fracture of the talus due to a benign tumor was retained. Unicameral bone cyst, ABC, and giant cell tumor were suspected. The patient was operated 2 weeks later. By an anterolateral approach of the ankle, with a skin incision of approximately 10 cm, anterior to the distal end of the fibula, curving toward the base of the fourth metatarsal, paying attention to the superficial fibular nerve. The superior bundle of the extensor retinaculum is transected. The extensor digitorum brevis tendon is split longitudinally and retracted, exposing the lateral aspect of the talar neck. The talus was exposed. A trepanation was made on the neck of the talus (Fig. 3) with a trocar and extended intra-lesional curettage was performed progressively using bone curettes of different sizes, revealing a spongious bone blood-filled mass (Fig. 4).

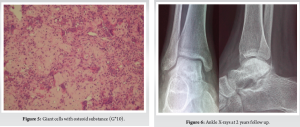

After curettage, the cavity was filled with an autologous cancellous iliac bone graft. The subtalar cortical breach, still covered by the articular cartilage, did not require any special action. The pathology of the curettage showed multinucleated osteoclastic giant cells associated with spindle cells, and intralesional osteoid foci (Fig. 5), concluding in a primary ABC.

A below-knee cast immobilization was completed for 2 months. Consolidation is obtained in 2 months, allowing full weight bearing. The patient was regularly followed up. At 2-month follow-up, ankle mobility was normal, comparable to the left ankle, with dorsal flexion at 25° and plantar flexion at 45°, and the follow-up X-ray at 2 years showed no signs of recurrence (Fig. 6). Five years later, the patient had no complaints.

The ABC is a rare benign osteolytic tumor, which is seen in 0.14/100,000 of the population per year [1,6]. Considered as a pseudo-tumor due to the lack of an epithelial lining, it occurs in the first two decades of life [1-3]. There are various forms of this benign lesion: Primary ABC, secondary ABC, solid ABC, or giant cell reparative granuloma, and soft-tissue aneurysmal cyst [1,2]. Secondary ABCs are less common and associated with trauma or another tumor, such as giant-cell tumors, chondroblastomas, or osteoblastomas. Fibrous dysplasia, chondromyxoid fibroma, nonossifying fibroma, osteosarcoma, chondrosarcoma, unicameral bone cyst, hemangioendothelioma; but the most frequent are the primary ABC, which represents 70% of all ABC diagnoses [2,3,6]. The case of our patient is a primary ABC. Since its first description, the etiology and pathogenesis of this tumor have been unclear and still controversial [3,6]. One theory states that ABC is the result of local circulatory disorders [1,3]. Other authors claim that it is a hereditary factor with chromosomal translocation abnormalities [1,2]. All these theories have shown that the etiopathogenesis of this lesion is multifactorial. This neoplastic process is frequent in young age (90% before the age of 20 years) and there is a slight female preponderance [1,6]; our patient was a 16-year-old girl. The preferential location of ABCs is the metaphysis of long bones, flat bones, and vertebrae; locations in the feet and hands are exceptional [1,3,6]. In the foot, they can involve the calcaneus, the navicular, and the talus [4,7,8]. The talus was a very rare location for this tumor; a few cases were found in the literature, and the subjects were slightly older than our case, aged 20–28 years [2-4,9]. Clinically, ABC can be revealed by pain, swelling, pathologic fracture, and neurologic symptoms when the axial skeleton is concerned [1,2]. The case reported was revealed by pain and pathologic fracture. The radiographic and CT features of ABC are not pathognomonic and are rather conflicting. Magnetic resonance imaging is the best choice to complement X-ray [2,6], but this imaging was not available in our country at the time we took care of the patient. The typical aspect in this exam is an expansive, lobular, or septate lesion. Multiple fluid levels may be detected on T2-weighted axial sequences [1]. Biopsy is essential for the diagnosis of ABC and can be performed by trocar or surgically, in the form of curettage-biopsy [2]. In our case, a surgical curettage-biopsy was carried out, followed at the same time by an autologous bone graft. Histologically, there is three types of ABC: The first one is the “classic or vascular” form which is a multiple sinusosidal blood-filled spaces separated by fibrous septa, with multinucleated giant cells and osteoids; the second histological form is non-cystic variant with solid gray-white tissue with hemorrhagic foci and abundant of fibroblastic and fibrohistocytic elements with osteoid and calcifying fibromyxoid tissue (solid form) and the last form is the “mixed” form, with elements of both vascular and solid types [2,3]. Our case corresponded to the first histological type. Although ABCs are benign lesions, occasionally they may behave as a locally aggressive, rapidly expanding, and locally destructive mass, which may be misdiagnosed as a malignant neoplasm [2,6]. The treatment of ABC included observation, intracystic injection, embolization, resection, and intralesional curettage alone or associated with a high-speed burr with/without argon beam coagulation, bone grafting, and also partial/total talectomy with tibiocalcaneal arthrodesis [2,4,10]. Furthermore, there are not some technologies, such as embolization, argon beam coagulation, in a low-income country like ours. That’s why we chose the option of curettage and bone grafting. Surgical access to the talus generally involves a medial malleolar osteotomy [11]; it can be done by the anteromedial approach [12], or even by the arthroscopic approach [9]. In our case, the approach was anterolateral with direct access to the neck of the talus, which was trephined; this allowed us to work easily. This access of the talus by non-articular way (neck of talus) could reduce the risk of tibiotalar arthrosis occurrence. ABCs are known to have a high recurrence rate (20–30%) due to remnants of lesions and usually reoccur within the first 12 months after initial treatment [2,13]. Even if the risk of reccurence exists with it, many authors have described excellent results with intralesional curettage and bone grafting for lytic lesions that were localized within the talus [4,14]. In our case, no recurrence was noted, even after 5 years of follow-up.

ABC is a rare lesion that must be evocated in front of a lytic lesion of the talus in a teenager. Its treatment is controversial, but intralesional curettage and bone grafting could be used in our context and allow us to hope for an excellent prognosis.

ABCs of the talus are a rare location that commonly affects growing children, predominantly females. The extensive involvement of the ilium mandates treatment that must also consider the stability of the adjoining hip joint. In growing age, bone grafting and curettage are recommended, but follow-up is necessary to look for recurrences.

References

- 1. Mascard E, Gomez-Brouchet A, Lambot K. Bone cysts: Unicameral and aneurysmal bone cyst. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res 2015;101:S119-27. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 2. Restrepo R, Zahrah D, Pelaez L, Temple HT, Murakami JW. Update on aneurysmal bone cyst: Pathophysiology, histology, imaging and treatment. Pediatr Radiol 2022;52:1601-14 [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 3. Nasri E, Reith JD. Aneurysmal bone cyst: A review. J Pathol Transl Med 2023;57:81-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 4. Sharma S, Gupta P, Sharma S, Singh M, Singh D. Primary aneurysmal bone cyst of talus. J Res Med Sci 2012;17:1192-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 5. Lodwick GS, Wilson AJ, Farrell C, Virtama P, Dittrich F. Determining growth rates of focal lesions of bone from radiographs. Radiology 1980;134:577-83. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 6. Docquier PL, Glorion C, Delloye C. Le kyste osseux anévrismal. EMC App Locom 2011;14:771. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 7. Jalan D, Gupta A, Elhence A, Nalwa A, Bharti JN, Elhence P. Primary aneurysmal bone cyst of the calcaneum: A report of three cases and review of literature. Foot (Edinb) 2021;47:101795. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 8. Gangopadhyay P, Emory C, Bonvillian J, Brackney C. Atypical presentation of navicular aneurysmal bone cyst in a symptomatic pediatric flatfoot deformity: A case report. J Foot Ankle Surg 2021;60:609-14. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 9. El Shazly O, Abou El Soud MM, Nasef Abdelatif NM. Arthroscopic intralesional curettage for large benign talar dome cysts. SICOT J 2015;1:32. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 10. Tripathy S, Varghese P, Panigrahi S, Karaniveed Puthiyapura L. Medial malleolar osteotomy for intralesional curettage and bone grafting of primary aneurysmal bone cyst of the talus. BMJ Case Rep 2021;14:e242452. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 11. Moonot P, Dakhode S, Karwande N. Novel surgical approach for large intraosseous subchondral cysts of talus: A case report and technical innovation. Cureus 2024;16:e52078. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 12. Vosoughi AR, Mozaffarian K, Erfani MA. Recurrent aneurysmal bone cyst of talus resulted in tibiotalocalcaneal arthrodesis. World J Clin Cases 2017;5:364-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 13. Steffner RJ, Liao C, Stacy G, Atanda JA, Attar S, Avedian R, et al. Factors associated with recurrence of primary aneurysmal bone cysts: Is argon beam coagulation an effective adjuvant treatment? J Bone Joint Surg Am 2011;93:e122-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 14. Chowdhry M, Chandrasekar CR, Mohammed R, Grimer RJ. Curettage of aneurysmal bone cysts of the feet. Foot Ankle Int 2010;31:131-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]