Cavernous hemangiomas of Hoffa’s fat pad are exceptionally rare vascular malformations that often mimic common knee pathologies and cause diagnostic delays, where MRI aids in accurate localization and characterization, histopathology confirms diagnosis and excludes malignancy, and complete en bloc excision ensures symptomatic relief, functional recovery, and prevention of recurrence, highlighting the need for early suspicion, appropriate imaging, and definitive management.

Dr. Praveen Manoharan, Department of Orthopaedics, Mahatma Gandhi Medical College and Research Institute, Puducherry, India. E-mail: medicothedoc@gmail.com

Introduction: Cavernous hemangiomas are benign vascular malformations composed of dilated, blood-filled channels, commonly occurring in cutaneous or subcutaneous tissues of the head, neck, or trunk. Their occurrence in the knee joint, particularly within Hoffa’s (infrapatellar) fat pad, is extremely rare. Patients usually present with chronic anterior knee pain, swelling, and sometimes mechanical symptoms. Due to the wide range of differential diagnoses for knee swellings, diagnosis is often delayed without appropriate imaging. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is pivotal for accurate localization, lesion characterization, and pre-operative planning, while complete surgical excision remains the treatment of choice.

Case Report: We present the case of a 35-year-old female with a 3-year history of persistent anterior knee pain and swelling. Clinical suspicion was broad, and MRI was performed, which revealed a well-defined cavernous hemangioma confined to the infrapatellar fat pad. The patient underwent en bloc surgical excision, which was completed successfully without complications. Postoperatively, she achieved complete symptomatic relief and regained normal knee function. Histopathological examination confirmed the diagnosis of cavernous hemangioma.

Conclusion: This case emphasizes the rarity of Hoffa’s fat pad cavernous hemangiomas, the diagnostic challenges they pose, and the value of MRI in establishing an accurate pre-operative diagnosis. Complete surgical excision provides excellent outcomes by relieving symptoms, preventing recurrence, and restoring knee function.

Keywords: Cavernous hemangioma, Hoffa’s fat pad, infrapatellar fat pad, knee swelling, en bloc excision, vascular malformation.

Cavernous hemangiomas are benign vascular malformations characterized by slow-flow venous channels lined by a single layer of endothelium and supported by a fibrous adventitia to form cystic lesions that often distort surrounding anatomy [1]. While one might generalize hemangiomas into three categories, namely, capillary, cavernous, and mixed, no one finds them clinically and pathologically equivalent [2]. Cavernous hemangiomas usually occur in cutaneous or subcutaneous tissue of the head, neck, and trunk, but may seldom occur in deeper structures such as the liver, brain, or musculoskeletal system [3]. Vascular malformations manifest infrequently within the locomotor apparatus but can result in severe impairment of mobility, functionality, and quality of life when they do appear [4]. The knee joint, which does not function as a normal full joint due to the immense functional loads and large ranges of motion that are expected to be developed at this site, is an uncommon location for cavernous hemangiomas, yet it is certainly a noteworthy one. These lesions may, clinically, demonstrate different manifestations: persistent swelling, pain aggravated by flexion or weight bearing, localized warmth, and the possibility of mechanical locking if intra-articular components are compromised [5]. Because these tumors are rare in the knee, misdiagnosis typically happens. The differential diagnosis may include, but is not limited to, synovial chondromatosis, giant cell tumors of the tendon sheath, pigmented villonodular synovitis, chronic bursitis, or meniscal pathologies, depending on the exact location of the lesion and the symptoms presenting [6]. Radiographic evaluation in the study helps to understand the extent, vascularity, and anatomic relationships of knee hemangiomas. Conventional X-rays may demonstrate some soft-tissue swelling or calcifications secondary to phleboliths, whereas advanced techniques such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are acceptable as the gold standard in the pre-operative workup [6]. MRI is best in differentiating vascular malformations from other neoplasms, accurately determining the anatomic extent of the lesion, and helping with surgical planning. Characteristic radiologic findings include patchy or lobulated areas of high T2 signal, with signal voids or septa corresponding to vascular channels and fibrous trabeculae [7]. Furthermore, a contrast-enhanced MRI may assist in outlining feeding vessels and perfusion characteristics of the lesion to better refine the surgical approach [8]. In selected cases, ultrasound or Doppler studies would also assist in confirming the vascular nature of the lesion, though these imaging modalities are rather limited for the assessment of deep or complex masses around the knee joint compared to MRI [9]. Histologically, cavernous hemangiomas display large vascular channels lined by endothelium with fibrous septa. Although the diagnosis is based on histopathological examination, the clinical and imaging correlations are often critical in separating hemangiomas from other hypervascular or hemorrhagic entities, such as malignant vascular tumors and reactive vascular proliferations [10]. In most cases, definitive treatment of symptomatic hemangiomas requires complete surgical excision to prevent recurrence, relieve pressure, or reduce discomfort [11]. However, in some patients, especially those with inoperable or large vascular malformations involving critical structures, adjunctive measures may be helpful, including sclerotherapy, embolization, or even targeted pharmacotherapies such as sirolimus when excision is impractical or incomplete [12]. Cavernous hemangiomas are slow-flow vascular malformations characterized by large, blood-filled channels lined by a single layer of endothelium. Although they most commonly occur in the skin, liver, and craniofacial regions, they can rarely be found in deeper structures such as synovial joints. The knee joint, with its complex anatomy and significant biomechanical demands, is an uncommon location for these lesions; rarer still is their occurrence in Hoffa’s (infrapatellar) fat pad, a well-vascularized structure located posterior to the patellar tendon [6]. Hoffa’s fat pad can be affected by a variety of pathologies that masquerade as more common knee disorders, including patellar tendinopathy, meniscal injuries, pigmented villonodular synovitis, or degenerative changes. As with other vascular anomalies, classification of hemangiomas versus vascular malformations has evolved over time, and the International Society for the Study of Vascular Anomalies (ISSVA) differentiates true hemangiomas-which display proliferative phases-from slow-flow venous malformations such as cavernous hemangiomas [13]. In adults, symptomatic intra-articular or peri-articular hemangiomas may present with nonspecific knee pain, swelling, and occasional mechanical locking if the lesion impinges on the joint space [5]. The absence of overt inflammatory signs often complicates early clinical diagnosis; patients may experience intermittent or chronic discomfort that is initially attributed to common knee pathologies. Plain radiographs can be normal or demonstrate soft-tissue swelling, calcifications (phleboliths), or, uncommonly, adjacent bone remodeling [14]. Consequently, MRI is the modality of choice for recognizing vascular malformations, distinguishing them from neoplastic processes, and elucidating lesion extent [8]. On T2-weighted sequences, cavernous hemangiomas typically display high signal intensity with lobulated septations, while T1-weighted images often show iso to hypo-intensity, with variable enhancement patterns after gadolinium administration [6,8]. Furthermore, Doppler ultrasound may confirm the vascular nature of a lesion but is limited in deep or complex knee regions [9]. Histopathological examination ultimately establishes the diagnosis. Cavernous hemangiomas exhibit large vascular channels lined by flattened endothelial cells, supported by fibrous septa, distinguishing them from capillary hemangiomas or more aggressive vascular tumors [10]. In managing symptomatic lesions, En bloc surgical excision remains the gold standard. Partial excision increases the likelihood of recurrence, as residual abnormal vasculature can proliferate, perpetuating symptoms [5]. Although these lesions are generally considered low-flow anomalies, intraoperative bleeding can be considerable, making meticulous hemostasis crucial. In cases involving extensive joint or soft-tissue infiltration, or when complete resection threatens vital structures, adjunctive therapies such as sclerotherapy or targeted pharmacological agents (e.g., sirolimus) may have a role [12,15]. Post-operative rehabilitation focuses on restoring range of motion, preventing arthrofibrosis, and strengthening peri-articular musculature to preserve knee function. Despite their benign nature, cavernous hemangiomas in Hoffa’s fat pad can produce substantial morbidity. They may cause persistent anterior knee pain, mechanical difficulties, and can significantly diminish a patient’s quality of life [16]. The rarity of these lesions and the variety of common knee problems underscore the need for heightened clinical suspicion. Knowledge of advanced imaging modalities, along with a structured diagnostic approach, expedites appropriate management and avoids unnecessary delays [4]. Ultimately, integrating surgical expertise, radiological assessment, and careful pathological evaluation fosters the best outcomes, minimizing post-operative complications and recurrence rates. This report adds to the limited body of literature describing the successful resection of a cavernous hemangioma confined to Hoffa’s fat pad and highlights the diagnostic vigilance required for such elusive presentations [17].

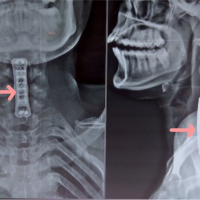

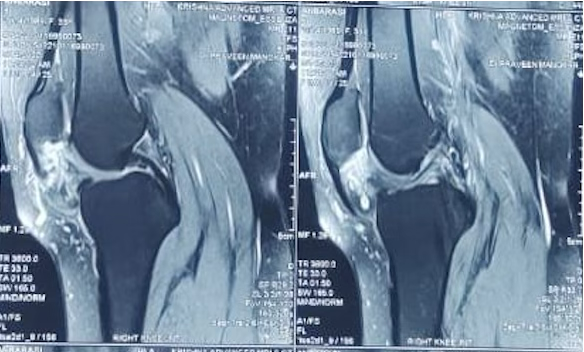

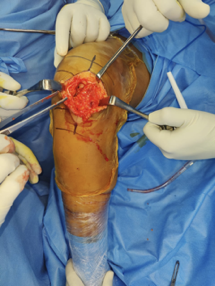

A 35-year-old female presented to the orthopedic outpatient department with a 3-year history of persistent anterior knee swelling and pain affecting her right knee. She denied any major inciting trauma, although she recalled a minor fall in adolescence, which she believed was unrelated. Over time, the swelling gradually increased in size, and her discomfort worsened with knee flexion or prolonged weight bearing. She had no constitutional symptoms such as fever, weight loss, or malaise. Her past medical history was unremarkable, and there was no significant family history of vascular malformations. On examination, the patient lay supine with neutral alignment of the lower limbs. A palpable swelling measuring approximately 5 cm × 4 cm was observed in the infrapatellar region just medial to the patellar tendon. There were no signs of skin discoloration, venous prominence, or sinus formation. Palpation elicited mild tenderness; however, there was no local rise in temperature. Knee flexion was possible from 0° to 130° with discomfort at the terminal arc, exacerbated by deep flexion. Initial plain radiographs showed a non-specific soft-tissue prominence in the same area without evidence of bony involvement or calcifications. An MRI of the right knee revealed a lobulated lesion in Hoffa’s fat pad measuring about 4.8 cm × 2.6 cm × 4.9 cm, hyperintense on T2-weighted sequences and displaying septations consistent with vascular channels. No extension into bone or joint cartilage was evident, and there were no features suggesting aggressive infiltration. Based on these findings, a vascular malformation-likely a cavernous hemangioma-was suspected. The patient was counseled regarding the need for surgical excision to alleviate symptoms and confirm the diagnosis. After pre-operative clearance and standard laboratory work-up, she underwent surgery under spinal anesthesia with a pneumatic tourniquet applied to the thigh. An anteromedial longitudinal incision was made over the infrapatellar area. Careful dissection revealed a well-defined vascular mass within Hoffa’s fat pad. En bloc resection was performed, ensuring clear margins. Hemostasis was secured, and the wound was closed in layers with a drain in place (Figs. 1, 2).

Figure 1: Plain radiograph of right knee antero-posterior and lateral view shows no bone lesion.

Figure 2: Sagittal T2 weighted magnetic resonance imaging shows loculated heterogenous lesion in in Hoffa’s fat pad right knee.

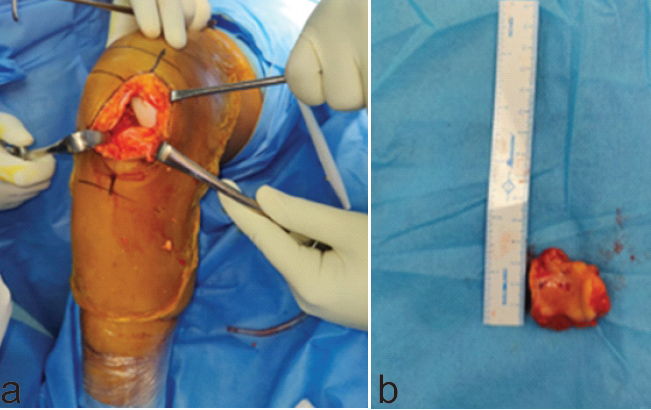

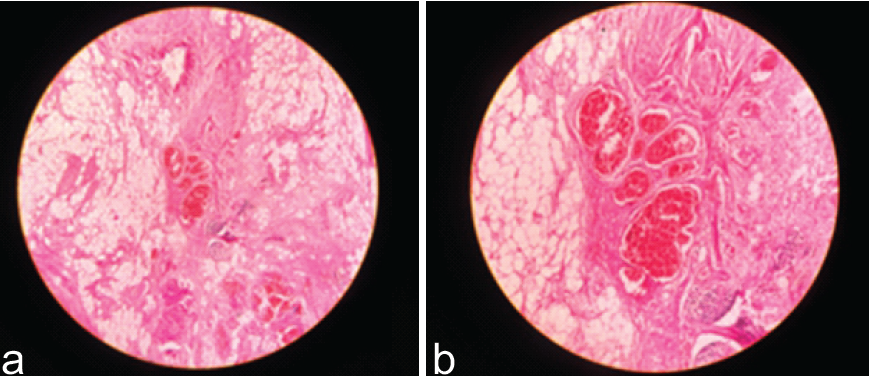

Gross examination of the surgical specimen showed a spongy, dark-red mass. Histopathological assessment confirmed the presence of large, blood-filled vascular channels lined by endothelium and separated by fibrous septa, consistent with a cavernous hemangioma. There were no atypical cells or evidence of malignancy. Postoperatively, the patient showed immediate pain relief and was mobilized with partial weight bearing on day 1. The drain was removed on day 2, and she progressed to near-complete knee extension and about 90° of flexion without significant discomfort by day 3. At 2 weeks postoperatively, the wound was well healed, and she had regained approximately 120° of flexion. She continued rehabilitation at home with quadriceps-strengthening exercises. At subsequent follow-ups, there were no clinical or radiological signs of recurrence (Fig. 3, 4, 5).

Figure 3: Mass found medial to patellar tendon.

Figure 4: (a) En bloc excision done with clear margins, (b) Resected vascular mass found within Hoffa’s fat pad was of size 6 cm × 3 cm × 5 cm.

Figure 5: (a) and (b) Histopathological assessment confirmed the presence of large, blood-filled vascular channels lined by endothelium and separated by fibrous septa.

In summary, Cavernous hemangiomas are uncommon in the musculoskeletal system, and their occurrence within Hoffa’s (infrapatellar) fat pad of the knee is exceptionally rare, with very few cases reported in the literature. The nonspecific presentation of chronic anterior knee pain and swelling often mimics common conditions such as meniscal pathology, tendinitis, or synovial disorders, leading to diagnostic delays. This case is unique in demonstrating the characteristic MRI findings of a cavernous hemangioma, confirmed by histopathology, and highlights the diagnostic challenge posed by such lesions. Furthermore, it emphasizes the effectiveness of complete en bloc excision, which not only achieved curative resection but also restored knee function without recurrence. The report adds valuable clinical and educational insight by stressing the importance of considering vascular malformations in the differential diagnosis of persistent anterior knee pain.

Cavernous hemangiomas, categorized as benign slow-flow vascular malformations, represent one subset within a diverse family of vascular anomalies [18]. Their identification and classification have been refined by organizations like the ISSVA, distinguishing hemangiomas – often proliferative in infancy – from vascular malformations that follow a more indolent course [13]. Such lesions can appear anywhere in the body but manifest only infrequently in load-bearing joints [19]. In the knee, various lesions-pigmented villonodular synovitis, meniscal pathologies, or other tumor-like processes–commonly occupy the differential diagnosis, contributing to frequent delays in diagnosing a vascular origin [20]. The presence of phleboliths on radiographs may offer a clue, yet their absence does not exclude a hemangioma [14]. Consequently, MRI has become the gold standard for confirming the vascular nature of the mass and delineating its anatomic boundaries [21]. When confined to Hoffa’s fat pad, these vascular lesions can produce chronic anterior knee swelling, pain, and mechanical problems. Histopathology is essential for definitive diagnosis, as it reveals large vascular channels lined by flattened endothelial cells, segregated by fibrous septations [22]. This distinguishes them from capillary hemangiomas with smaller lumens or malignant vascular tumors such as angiosarcomas [23]. Immunohistochemical markers (e.g., CD31, CD34) may be employed to confirm endothelial origin if needed [24]. Complete surgical excision remains the cornerstone of therapy for symptomatic cavernous hemangiomas [25]. In smaller, well-defined lesions like the one described in this case, En bloc resection is frequently curative, with a minimal risk of recurrence when margins are free of disease [26]. In contrast, larger or more infiltrative malformations may necessitate a multimodal approach that includes pre-operative embolization or sclerotherapy [27]. The advent of pharmacological agents such as sirolimus has further expanded treatment possibilities, particularly for unresectable or complex lesions, by inhibiting endothelial proliferation [15]. Intraoperative bleeding can be controlled effectively with a tourniquet, given that these lesions, while low-flow, can still exhibit substantial vascularity [16]. Postoperatively, attentive wound care and early mobilization-combined with physical therapy-can minimize joint stiffness, muscle atrophy, and arthrofibrosis [28]. Some authors advocate arthroscopic or minimally invasive approaches for smaller intra-articular lesions, but open techniques remain indispensable for large or anatomically intricate masses [27]. Regardless of approach, the primary objective is to achieve complete resection while preserving critical structures [25]. Follow-up imaging may be considered if there is suspicion of recurrence or incomplete resection [21]. In the setting of Hoffa’s fat pad lesions, early diagnosis and definitive surgery restore function, alleviate pain, and prevent further joint compromise [29]. Ultimately, awareness of this uncommon entity among orthopedic surgeons and radiologists fosters timely referral for specialized care, ensuring a successful outcome in these rare but clinically significant cases [30].

Cavernous hemangiomas arising from Hoffa’s fat pad are rare vascular malformations that can mimic various common knee pathologies, often leading to delayed diagnosis. MRI is the most reliable tool for identifying and characterizing these lesions, and histopathological examination provides definitive confirmation. Complete surgical excision en bloc is curative for symptomatic lesions, with meticulous attention to hemostasis and joint structure preservation. Early rehabilitation is integral to restore knee function, prevent stiffness, and facilitate a return to normal activities. This case highlights the importance of considering vascular etiologies in chronic anterior knee pain and reinforces the need for a high index of suspicion, especially when clinical and basic imaging findings are inconclusive.

Cavernous hemangiomas of Hoffa’s fat pad are exceptionally rare and often present with chronic anterior knee pain and swelling. Due to their nonspecific symptoms, they can be easily misdiagnosed as more common knee disorders. MRI plays a pivotal role in accurate diagnosis and pre-operative assessment. Histopathological confirmation is mandatory for definitive diagnosis. Complete surgical excision offers excellent outcomes with symptom resolution and minimal recurrence risk.

References

- 1. Mulliken JB, Glowacki J. Hemangiomas and vascular malformations in infants and children: A classification based on endothelial characteristics. Plast Reconstr Surg 1982;69:412-22. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 2. Greene AK, Rogers GF, Mulliken JB. Intraabdominal and intrathoracic lesions of vascular origin. Semin Pediatr Surg 2006;15:124-32. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 3. Kilcline C, Frieden IJ. Infantile hemangiomas: How common are they? A systematic review of the medical literature. Pediatr Dermatol 2008;25:168-73. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 4. Lee BB, Baumgartner I, Berlien HP, Bianchini G, Burrows PE, Do YS, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of venous malformations. Consensus document of the International Union of Phlebology (IUP): Updated 2020. Int Angiol 2020;39:97-127. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 5. De Ponti A, Sansone V, Malcherè M, Godina M, Mariani PP. Synovial hemangioma of the knee: A diagnostic challenge. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2002;10:57-61. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 6. Greenspan A. Orthopedic Imaging: A Practical Approach. 6th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2014. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 7. Van Der Vleuten CJ, Kater A, Wijnen MH, Spauwen PH. Evaluation of diagnostic procedures and management of hemangiomas: A retrospective study. Int J Low Extrem Wounds 2005;4:12-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 8. Colletti PM, Lee K. Contrast-enhanced MR angiography of vascular malformations: Technique and clinical applications. Magn Reson Imaging Clin N Am 2012;20:641-50. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 9. Cantisani V, Grazhdani H, Drakonaki E, Filice S, Ricci P, Schafernak K, et al. Musculoskeletal ultrasound study of synovial vascular disorders. Eur J Radiol 2012;81:3026-31. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 10. Fletcher CD, Bridge JA, Hogendoorn PC, Mertens F. WHO Classification of Tumours of Soft Tissue and Bone. 4th ed. Lyon: IARC Press; 2013. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 11. Kanner WA, Galambos C. Vascular malformations and hemangioma. Semin Diagn Pathol 2004;21:88-100. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 12. Adams DM, Trenor CC 3rd, Hammill AM, Vinks AA, Patel MN, Chaudry G, et al. Efficacy and safety of sirolimus in the treatment of complicated vascular anomalies. Pediatrics 2016;137:e20153257. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 13. ISSVA. International Society for the Study of Vascular Anomalies Classification for Vascular Anomalies. Revision 2018. Available from: https://www.issva.org/classification [Last accessed on 2025 May 16]. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 14. Smith WS, Pringle RG, Murdoch G. Phleboliths in hemangiomas. A radiological sign. Radiology 1960;74:486-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 15. Stella M, Clementi M, Dolcino D, Martinetti C, Cavoretto D, Gennaro L, et al. Current concepts in the pathogenesis and treatment of vascular anomalies: A new perspective on the role of sirolimus (rapamycin). J Pediatr Surg 2020;55:2245-53. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 16. Sung MS, Kang HS, Suh JS, Lee HM, Cho JH, Kim JY. Synovial hemangioma of the knee: Imaging findings in six patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1998;171:237-41. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 17. Freedman RS, Ramirez PT. Rare tumors of the musculoskeletal system: Strategies for diagnosis and management. Surg Oncol Clin N Am 2005;14:201-19. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 18. Chen WL, Huang GS, Lee HS, Tiu CM, Chang CY. Peripheral hemangiomas and vascular malformations in infancy and childhood. J Med Ultrasound 2013;21:3-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 19. Kransdorf MJ, Murphey MD. Imaging of Soft Tissue Tumors. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2006. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 20. Granowitz SP, D’Antonio J, Mankin HJ. Synovial chondromatosis. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1976;58:789-92. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 21. Murphey MD, Fairbairn KJ, Parman LM, Baxter KG, Parsa MB, Smith WS. From the archives of the AFIP. Musculoskeletal angiomatous lesions: Radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics 1995;15:893-917. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 22. Kransdorf MJ. Benign soft-tissue tumors in a large referral population: Distribution of specific diagnoses by age, sex, and location. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1995;164:395-402. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 23. Weybright P, Sundaram M, McGuire MH. MR imaging of soft-tissue masses: Significance of tumor size, location, and depth. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1998;170:1247-52. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 24. Pretorius PM, Quaghebeur G. The role of MRI in fetal medicine. Semin Perinatol 2009;33:281-90. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 25. Dompmartin A, Vikkula M, Boon LM. Venous malformation: Update on aetiopathogenesis, diagnosis and management. Phlebology 2010;25:224-35. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 26. Chiller KG, Passaro D, Frieden IJ. Hemangiomas of infancy: Clinical characteristics, and demographic data, prospective analysis of 614 cases. Pediatr Dermatol 2002;19:348-55. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 27. Berenguer B, Burrows PE, Zurakowski D, Mulliken JB. Sclerotherapy of craniofacial venous malformations: Complications and results. Plast Reconstr Surg 1999;104:1-11; discussion 12-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 28. Li Q, Gao S, Jiang B, Li X, Zheng J. Surgical excision and arthroscopic therapy for synovial hemangioma of the knee. J Pediatr Surg 2012;47:1722-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 29. Takahashi S, Watanabe H, Asada Y, Sudo A. Synovial hemangioma of the knee in a 10-year-old female: A case report. J Med Case Rep 2012;6:170. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 30. Schmid S, Karrer S, Kunzi W, Burg G, Hafner J. The hamartoma concept-common histogenesis of vascular and other hamartomas of soft tissue and skeletal system. Dermatology 1997;195:355-61. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]