Sagittal spinopelvic radiograph should be obtained to understand the interplay between the spinal regions rather than looking at a single segment alone.

Dr. Sudhir Singh, Department of Orthopaedics, Teerthanker Mahaveer Medical College and Research Centre, Moradabad, Uttar Pradesh, India. E-mail: susi59@live.in

Introduction: Low back pain (LBP) is a global health problem with a multifactorial etiology. Many clinicians believe that a change in the lumbar lordosis is a cause of LBP. The normal range of lordosis has not yet been agreed on. Consequently, the practice of measuring the lordosis needs to be re-evaluated. Our study aims primarily to determine the lumbar lordotic angle (LLA) and lumbosacral angle (LSA) in individuals with and without chronic LBP (CLBP), and secondarily to analyze the correlation between age, gender, body mass index (BMI), and pain severity.

Materials and Methods: In this prospective case–control research, 200 adults of both genders participated. The participants were split into two groups: The control group and the case group. One hundred individuals with persistent LBP were part of the case group. In addition, 100 subjects who were matched for age, gender, and BMI were included in the control group. Lateral projection radiographs in a standing position of the lumbar spine were taken for all the subjects. The lordosis angles (LLA and LSA) were recorded by a radiologist, who was blinded to the subjects’ clinical findings.

Results: There were 100 subjects each in the case group and the control group. Both groups were similar with respect to age (P = 0.407), gender (P = 0.315), and mean BMI (P = 0.239). The mean LSA was 34.17 ± 5.86 (M: 35.19 ± 6.86; F: 33.55 ± 5.07) in the cases group and 36.69 ± 6.72 (M: 37.68 ± 6.78; F: 35.87 ± 6.63) in the control group (P = 0.001). The mean LLA was 50.04 ± 9.09 (M: 53.99 ± 8.93; F: 48.25 ± 8.55) in cases and 49.60 ± 9.77 (M: 48.78 ± 9.69; F: 50.30 ± 9.88) in controls (P = 0.737). Subjects with CLBP show decreased LSA in 31–40 years of age (P = 0.013), in females (P = 0.02), and in overweight individuals (P = 0.002), and increased LLA in males (P = 0.001), but the difference in angles was only 2–4°. Neither LSA nor LLA shows any association or correlation with age, gender, BMI, or Visual Analog Scale (VAS).

Conclusions: The results have shown that LLA does not vary in those with and without nonspecific CLBP. LSA and LLA do not show a clear association and show an insignificant weak correlation with age, gender, BMI, and VAS in cases as well as controls.

Keywords: Low back pain, lumbosacral angle, lumbar lordotic angle, lumbar lordosis, sagittal radiograph, spinopelvic parameter.

Low back pain (LBP) is a global health problem; some people experience it for a limited period, but in others, it may be prolonged and become chronic, thus causing high cost of health care and loss of workdays and reduced productivity [1,2]. Chronic LBP (CLBP) is defined as pain that is located above the inferior gluteal folds and below the costal border, lasting more than 12 weeks, with or without leg pain [3]. LBP is labelled as non-specific if there is no known patho-anatomical cause [3,4,5]. The etiology of LBP is multifactorial and relatively enigmatic. Many clinicians believe that a change in the lumbar lordosis is a cause of LBP, but not all believe this, as varying results have been reported [6,7,8,9,10,11,12]. It is generally believed that lordosis in an individual depends on multiple factors such as age, gender, body mass index, ethnicity, and has been extensively reported [13,14,15]. The normal range of lordosis has not yet been agreed on for any gender, race, age, or geographical area [13]. Consequently, the practice of measurement of the lordosis and other parameters in sagittal radiographs needs to be re-evaluated.

Aims of the study

We hypothesized that the lumbar lordotic angle (LLA) and lumbosacral angle (LSA) would correlate with neck pain. Our study aims (1) to determine the LLA and LSA in those with and without nonspecific CLBP and (2) to analyze the correlation of the confounding factors such as age, gender, body mass index (BMI), and duration of symptoms and pain severity, with LLA and LSA.

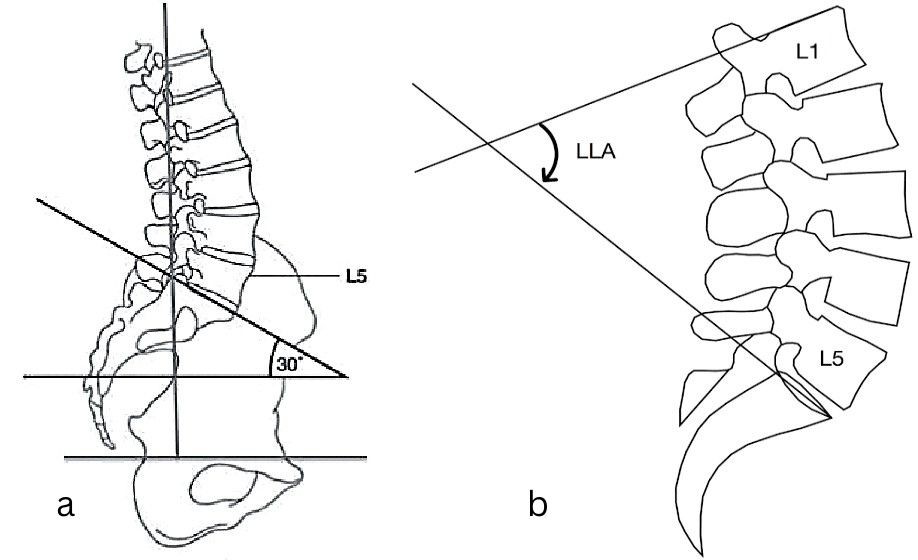

The prospective case–control study was conducted after the study proposal was cleared by the College Research Committee and the Institutional Ethical Committee. The sample size was calculated statistically as 100 cases as per the formula: n = z2 p (100–p)/e2. All participants were enrolled after written informed consent. 100 adult subjects of either gender or age between 18 and 50 years, presenting to the outpatient department, with complaints of LBP for more than 3 months and diagnosed with non-specific LBP, were enrolled as cases. Patients were excluded if there was any suspicion or history of “Red Flags”, i.e., (i) significant trauma, (ii) malignancy, (iii) steroid use, (iv) drug abuse, (v) immunocompromised state, (vi) spinal and/or lower limb structural deformity, (vii) inflammatory or infective conditions of spine, (viii) neuromuscular conditions affecting the spine or lower limbs, (ix) systemic disease with concomitant signs of infection, (x) Cauda Equina syndrome or radiculopathy, and (xi) degenerative and osteoporotic spine. Similarly, 100 healthy volunteers with age, gender, and BMI matched aged 18–50 years with no complaints of LBP were taken as controls. Two radiological parameters, LLA and LSA, were selected for evaluation on digital radiographs to assess lumbar lordosis. A lateral view of the lumbar spine was taken with the patient standing in a relaxed posture at a 90 cm distance from the X-ray tube. An expert radiologist, blinded to subjects’ clinical findings, calculated and recorded the LSA and LLA on DICOM images using HOROS Software. LSA was defined as the angle between the superior endplate of the first sacral vertebrae and a horizontal reference on sagittal imaging of the lumbosacral spine [16] (Fig. 1a). LLA was defined as the angle between the superior endplate of L1 vertebrae and the superior endplate of S1 vertebrae [16] (Fig. 1b). The Visual Analog Scale (VAS) was used to assess the severity of pain [17]. Zero (0) was defined as no pain, 1–2 as mild pain, 3–6 as moderate pain, and 7–10 as severe pain. Subjects were stratified as underweight (30 kg/m2), normal (18.5–24.9 kg/m2), overweight (25–29.9 kg/m²), and obese (>30 kg/m2) according to their BMI. The data were analyzed by Statistical Package for the Social Sciences software, version 25.0. by IBM, Chicago. In all statistical tests, a confidence interval (CI) of 95% was adopted, and a P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Figure 1: (a) Lumbosacral angle was defined as the angle between the superior endplate of the first sacral vertebrae and a horizontal reference on sagittal imaging of the lumbosacral spine, (b) Lumbar Lordotic angle was defined as the angle between the superior endplate of L1 vertebrae and the superior endplate of S1 vertebrae.

Demographic profile

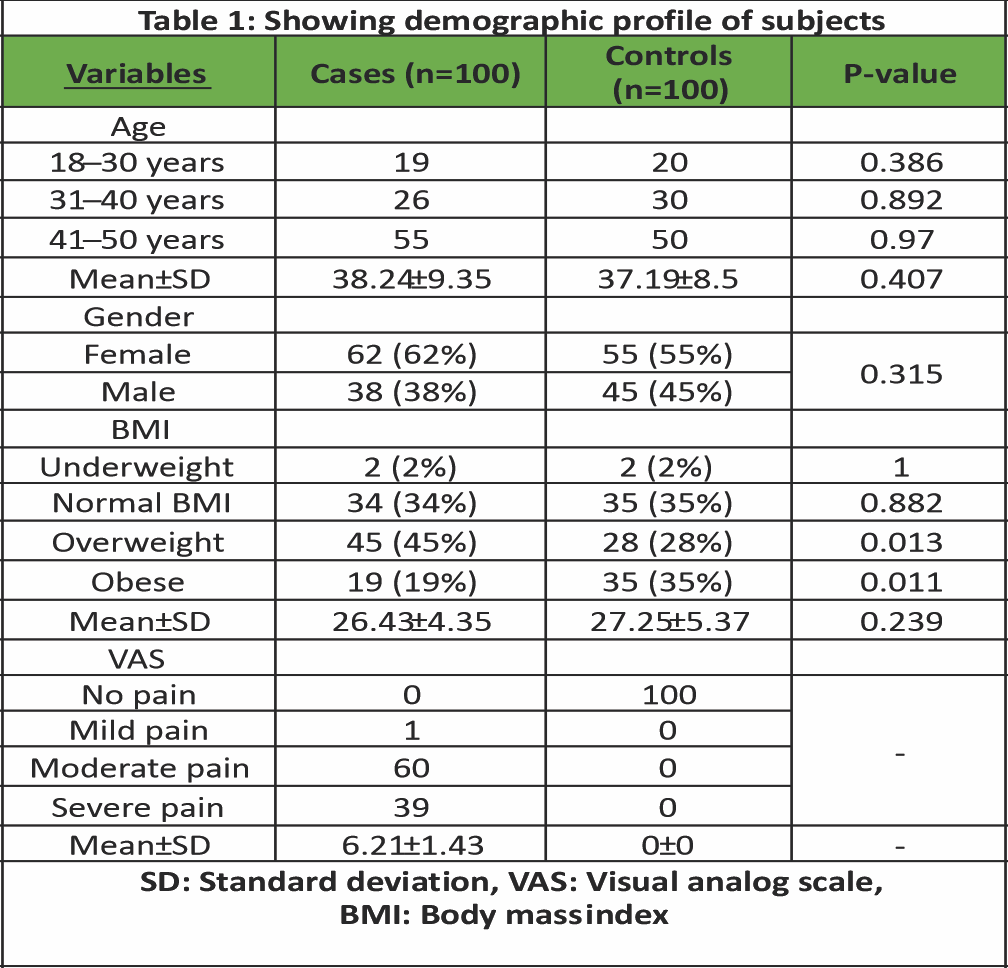

There were 100 subjects each in the case group and the control group. The mean age of subjects in the case group was 38.24 ± 9.35 years, and in controls it was 37.19 ± 8.5 years (P = 0.407). Age-wise distribution of subjects in each age group was similar (18–30 years: P = 0.386; 31–40 years: P = 0.892, and 41–50 years: P = 0.97, respectively) (Table 1).

Table 1: Showing demographic profile of subjects

The mean BMI of the case group was 26.43 ± 4.35 kg/m2, and that of the control group was 27.25 ± 5.37 kg/m2. The number of subjects in the overweight category was significantly more in the case group (P = 0.013), but in the obese category, the number of normal healthy subjects was significantly more than in the LBP group (P = 0.011). In the underweight and normal weight categories, the number of subjects was comparable in both the LBP group and the healthy group (P > 0.05). Overall, both the cases and control groups were similar with respect to age (P = 0.407), gender (P = 0.315), and mean BMI (P = 0.239). One subject had mild pain, 60 subjects had moderate pain, and 39 had severe pain, with a mean VAS score of 6.21 ± 1.43 (Table 1).

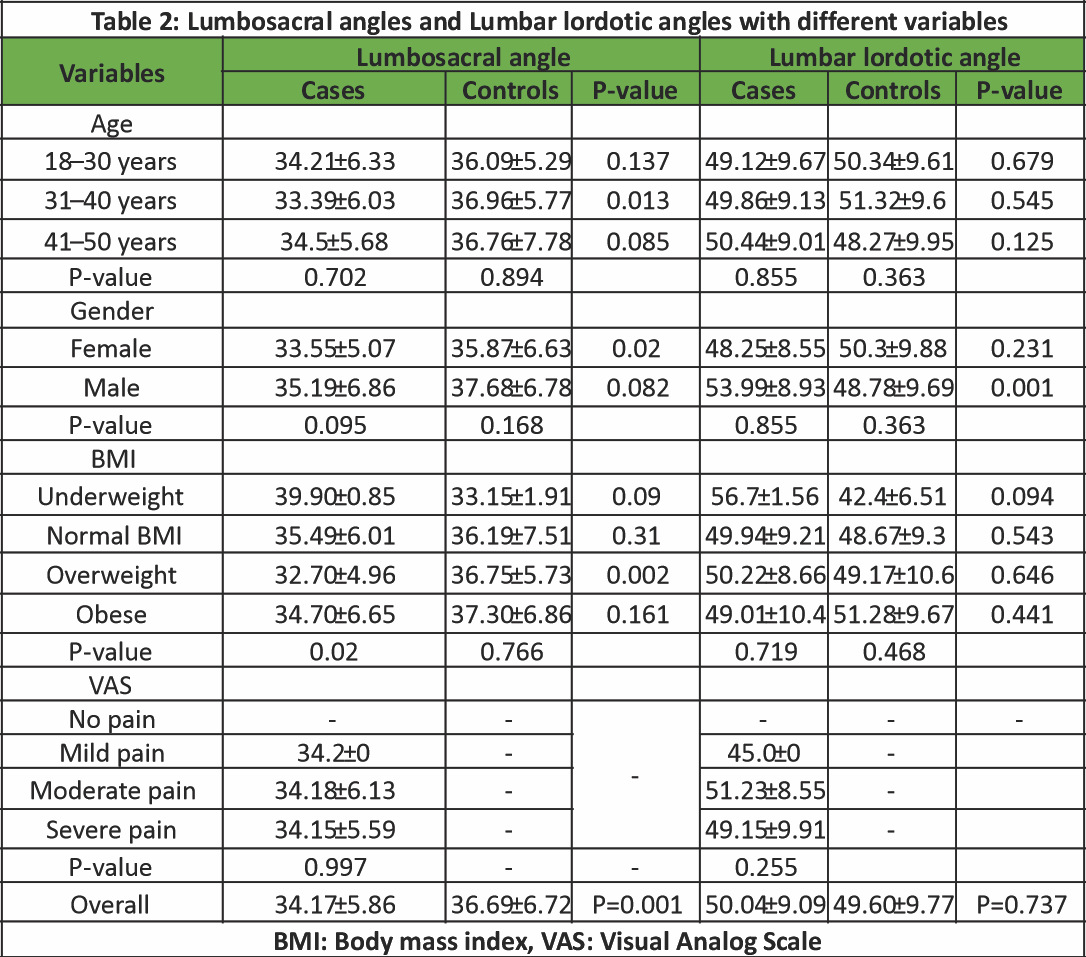

LSA

The mean LSA was recorded as 34.17 ± 5.86 (male: 35.19 ± 6.86; female: 33.55 ± 5.07) in the case group and as 36.69 ± 6.72 (male: 37.68 ± 6.78; female: 35.87 ± 6.63) in the control group, which was significantly less than controls (P = 0.001) (Table 2).

Table 2: Lumbosacral angles and Lumbar lordotic angles with different variables

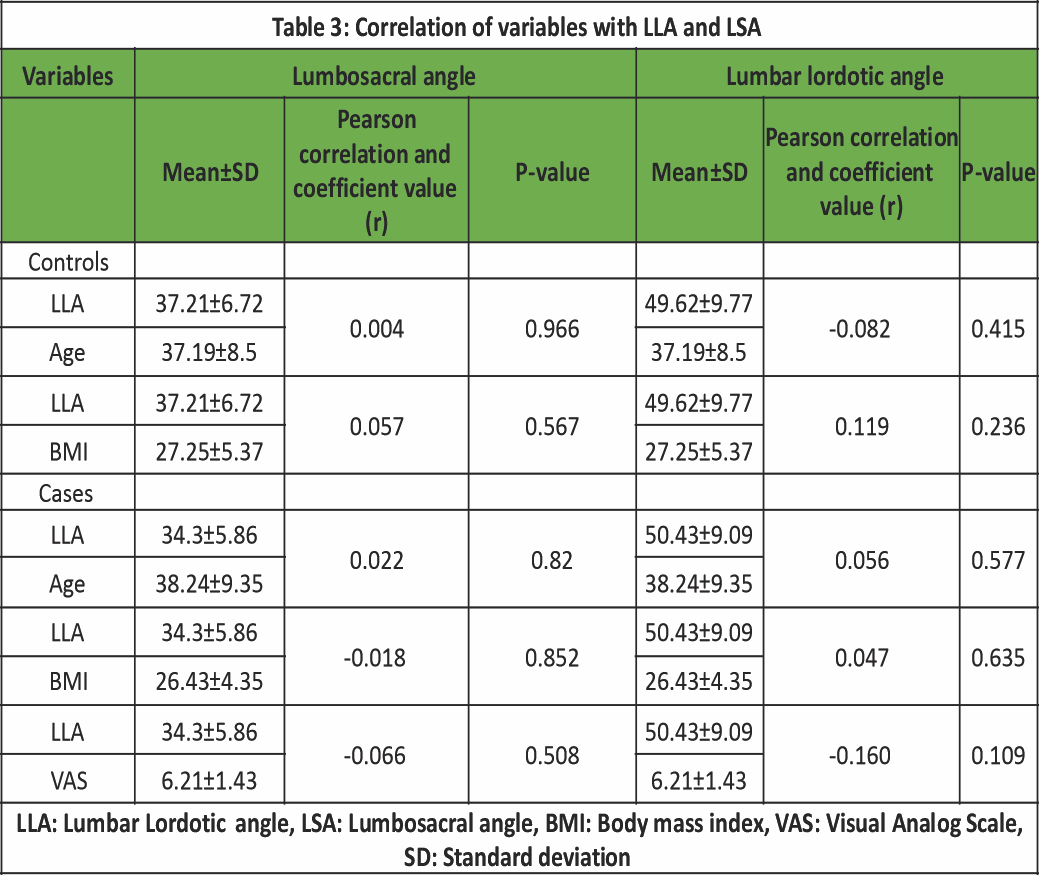

The study results show that LSA did not vary significantly among age subgroups in the LBP group (P = 0.702) and also in normal healthy subjects (P = 0.894). However, the LSA was significantly less in LBP cases of 31–40 years of age (P = 0.013). LSA in males and females does not differ significantly in the LBP group (P = 0.095) and also in healthy persons (P = 0.168). However, LBP females had significantly less LSA than healthy females (P = 0.02). LSA does not differ significantly within BMI categories in healthy individuals (P = 0.766). LBP patients show significantly less value of LSA in the overweight category (P = 0.02). Within sub-categories of BMI, the BMI of cases and controls was similar in underweight, normal, and obese categories (P ≥ 0.05). LSA of LBP patients in the overweight category is significantly less (P = 0.002). LSA was similar in LBP patients and the healthy population in underweight (P = 0.090), normal (P = 0.310), and obese categories (P = 0.161), but in the overweight category, the LBP cases show significantly less LSA than that of healthy individuals in the same category (P = 0.002). LSA did not vary significantly with VAS in the mild, moderate, and severe pain categories (P = 0.997) (Table 2). In controls, there was an insignificant and very weak positive correlation found between LSA with age (r = 0.004, P = 0.966) and BMI (r = 0.057, P = 0.567). In cases, an insignificant and very weak positive correlation was found between LSA and age (r = 0.022, P = 0.820) and a very weak negative correlation of LSA with BMI (r = −0.018, P = 0.852 and VAS (r = −0.066, P = 0.508) (Table 3).

Table 3: Correlation of variables with LLA and LSA

LLA

The mean LLA was recorded as 50.04 ± 9.09 (male: 53.99 ± 8.93; female: 48.25 ± 8.55) in cases and as 49.60 ± 9.77 (Male: 48.78 ± 9.69; Female: 50.30 ± 9.88) in controls, which is similar to controls (P = 0.737) (2). LLA is similar in all age sub-groups in cases (P = 0.855) and in controls (P = 0.363). LLA in each age subgroup was similar in cases and controls (P > 0.05). LLA in males and females, in both cases and controls, was similar (male: P = 0.855; female: P = 0.363). LLA was similar in females among cases and controls (P = 0.231), but males showed significantly higher values of LLA than females in LBP patients (P = 0.001). The study also shows that LLA is similar in all BMI sub-categories in cases (P = 0.719). With regards to BMI, LLA is similar in both cases and controls in each BMI sub-category (P > 0.05). LLA was also similar in the mild, moderate, and severe subgroups of VAS (P = 0.255) (Table 2). A non-significant, very weak negative correlation was found between LLA and age (r = −0.082, P = 0.415) and a weak positive correlation with BMI (r = 0.119, P = 0.236) in controls. The case group shows a non-significant, very weak positive correlation found of LLA with age (r = 0.056, P = 0.577) and BMI (r = 0.047, P = 0.635), with a very weak negative correlation of LLA with VAS score (r = −0.160, P = 0.109) (Table 3).

Demographic profile

Individuals above 50 years of age were not included to avoid people with osteoporotic and degenerative spines with marginal osteophytes. The age, gender, and BMI of subjects were similar in the case and control groups, showing that the composition of the groups was homogenous (P > 0.05) except that the number of subjects in the overweight BMI category was higher in the healthy groups (P = 0.013).

LSA

LSA in LBP cases was significantly less than that of healthy people (P = 0.001), suggesting an association with sacral slope. The difference in LSA between the groups was only 2–3°.

LSA in those with LBP was similar to that of those without LBP with respect to age (P = 0.702 and P = 0.894, respectively), showing no association of LSA with age. However, in 31–40 years of age subgroup, subjects with LBP show significantly less LSA (P = 0.013) than their counterpart in healthy subjects, indicating an association of age with LSA in 31–40 years of age subgroup, although the difference between the two groups is only 30. Similarly, gender-wise, the LBP patients show less LSA than healthy subjects, but the difference was not significant (P = 0.095 and P = 0.894, respectively). The females with back pain had lower LSA than healthy females, but not in males. The difference in angles was again only 20–30. The decrease in LSA did not cause a corresponding increase in LLA of female LBP patients. The LBP patients of the underweight category showed more LSA; meanwhile, the overweight category showed less LSA than healthy persons in the same BMI category. However, this change was also not reciprocated in the value of LLA in cases (Table 2). We did not find any association of sacral slope and the severity of pain, as the LSA was similar in those having mild, moderate pain, or severe pain. In healthy individuals, we found only an insignificant and very weak positive correlation between LSA and age (r = 0.004, P = 0.966) and BMI (r = 0.057, P = 0.567). Back pain patients also showed an insignificant and very weak positive correlation with age (r = 0.022, P = 0.820) and a very weak negative correlation with BMI (r = −0.018, P = 0.852) and VAS (r = −0.066, P = 0.508) (Table 3).

LLA

LLA of back pain patients was not different from that of healthy subjects (P = 0.737), showing no association with back pain. LSA was similar (P ≥ 0.5) in back pain cases and healthy individuals as a whole group, and also in various age subgroups. This indicates that age is not associated with back pain. Similarly, the lordotic angle was similar (P > 0.05) in males and females in both groups, indicating no association of lordosis with gender. However, males with back pain had more lordosis than males of the normal group without showing a decrease in LSA (Table 2). LLA in the case group did not differ from the healthy individuals group as a whole, and also in the subcategories of BMI. This implies that LLA remains unchanged with variations of BMI and is not associated with BMI. The LLA did not show any association with the severity of pain, as it did not vary significantly in those having mild, moderate pain, or severe pain. Our study has shown an insignificant and very weak negative correlation with age (r = −0.082, P = 0.415) and a weak positive correlation with BMI (r = 0.119, P = 0.236) in controls. The case group shows a non-significant, very weak positive correlation with age (r = 0.056, P = 0.577) and BMI (r = 0.047, P = 0.635), with a very weak negative correlation with VAS score (r = −0.160, P = 0.109) (Table 3). The influence of age, gender, and body weight has been denied by many authors in the last decade [10,12,13,14,18,19,20,21,22]. Furthermore, many recent reports are available reporting no role of LSA and LLA with CLBP [10,12,13,21,23,24]. We also did not find any association of LSA and LLA with CLBP in our study. LBP patients in 31–40 years of age group, of female gender and of overweight category showing 2–4° less values of LSA and male patients showing more values of LLA than in healthy group, does not necessarily mean that LLA and LSA are the cause of back pain since, the rest of the back pain patients do not show any difference in LSA and LLA with healthy persons. It has been reported earlier that variations in lumbar lordosis are common in the general population and are not necessarily indicative of pathology [22]. Furthermore, lumbar lordosis is highly variable and influenced by a multitude of factors, which complicates its use as a diagnostic measure [13]. The variation of 2–4° is well within normative values (LLA: 30–80°; LSA: 33–49°) of these parameters [25]. These minimal variations can be attributed to measuring error due to marginal osteophytes and should not be taken as a conclusive sign. It has been reported earlier that a reciprocal relationship between the sacral slope and the lumbar curvature exists, and both are essential components of the overall sagittal alignment of the spine [24]. We did not find this concept working in our study. LBP patients who had shown a significant decrease in LSA values by 2–3° failed to show any corresponding increase in lumbar lordosis, and when the lordosis had decreased, the sacral slope did not show any reciprocal change in sacral slope. It cannot be said with certainty that lower values of LSA in the normal weight category are the “cause of” or the “effect of” back pain. We hypothesize that, if lower values of LSA are the “cause,” then it should be reflected in the overweight and obese categories as well. Second, we do not have the values of these parameters before pain to say with certainty that pain is the only variable to “effect” this change. Over the last few decades, many countries have issued clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) for the diagnosis and treatment of LBP [3]. Earlier CPGs were based on recommendations of the clinicians, but more evidence-based CPGs have recently emerged with implementation strategies for the management of nonspecific LBP [26]. None of these guidelines encourages radiography for diagnosis or treatment, unless “red flag signs” are present, to avoid harmful radiation exposure to the patient. Our results have shown that assessment of LSA and LLA in sagittal radiographs, in non-specific CLBP patients, does not differ from that of healthy individuals. Hence, assessing them would not give any additional insights into the pathophysiology of pain and help in formulating the treatment plan for clinicians.

Limitations

One of the major limitations of this research was that the associated risk factors, such as psychological causes (depression, stress, anxiety, cognitive variables, sleep problems, social support, personality, and behavior), and individual causes (work-related, workplace-related, and working posture), were not assessed [27,28]. Second, a lateral view of the whole spine radiograph in a relaxed standing posture was not asked for, which may have provided a deeper insight into the cause of LBP.

The results have shown that LLA does not vary in those with and without LBP. The LSA was significantly lower in patients with LBP. LSA and LLA do not show a clear association and show an insignificant weak correlation with age, gender, BMI, and VAS in cases as well as controls.

The clinical message is that the degree of lordosis has no relation with CLBP and is independent of age, gender, and BMI.

References

- 1. GBD 2017 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990-2017: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 2018;392:1789-858. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 2. Katz JN. Lumbar disc disorders and low-back pain: Socioeconomic factors and consequences. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2006;88 Suppl 2:21-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 3. Nicol V, Verdaguer C, Daste C, Bisseriex H, Lapeyre É, Lefèvre-Colau MM, et al. Chronic low back pain: A narrative review of recent international guidelines for diagnosis and conservative treatment. J Clin Med 2023;12:1685. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 4. Maher C, Underwood M, Buchbinder R. Non-specific low back pain. Lancet 2017;389:736-47. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 5. Qaseem A, McLean RM, O’Gurek D, Batur P, Lin K, Kansagara DL, et al. Nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic management of acute pain from non-low back, musculoskeletal injuries in adults: A clinical guideline from the American college of physicians and American academy of family physicians. Ann Intern Med 2020;173:739-48. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 6. Youdas JW, Garrett TR, Egan KS, Therneau TM. Lumbar lordosis and pelvic inclination in adults with chronic low back pain. Phys Ther 2000;80:261-75. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 7. Nourbakhsh MR, Moussavi SJ, Salavati M. Effects of lifestyle and work-related physical activity on the degree of lumbar lordosis and chronic low back pain in a middle East population. J Spinal Disord 2001;14:283-92. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 8. Murrie VL, Dixon AK, Hollingworth W, Wilson H, Doyle TA. Lumbar lordosis: Study of patients with and without low back pain. Clin Anat 2003;16:144-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 9. Shayesteh Azar M, Talebpour F, Alaee AR, Hadinejad A, Sajadi M, Nozari A. Association of low back pain with lumbar lordosis and lumbosacral angle. J Mazandaran Univ Med Sci 2010;20:9-15. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 10. Laird RA, Gilbert J, Kent P, Keating JL. Comparing lumbo-pelvic kinematics in people with and without back pain: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2014;15:229. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 11. Caglayan M, Tacar O, Demirant A, Oktayoglu P, Karakoc M, Cetin A, et al. Effects of lumbosacral angles on development of low back pain. J Musculoskelet Pain 2014;22:251-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 12. Tatsumi M, Mkoba EM, Suzuki Y, Kajiwara Y, Zeidan H, Harada K, et al. Risk factors of low back pain and the relationship with sagittal vertebral alignment in tanzania. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2019;20:1-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 13. Been E, Kalichman L. Lumbar lordosis. Spine J 2014;14:87-97. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 14. Dreischarf M, Albiol L, Rohlmann A, Pries E, Bashkuev M, Zander T, et al. Age-related loss of lumbar spinal lordosis and mobility-a study of 323 asymptomatic volunteers. PLoS One 2014;9:e116186. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 15. Tsuji T, Matsuyama Y, Sato K, Hasegawa Y, Yimin Y, Iwata H. Epidemiology of low back pain in the elderly: Correlation with lumbar lordosis. J Orthop Sci 2001;6:307-11. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 16. Pourahmadi M, Sahebalam M, Dommerholt J, Delavari S, Mohseni-Bandpei MA, Keshtkar A, et al. Spinopelvic alignment and low back pain after total hip arthroplasty: A scoping review. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2022;23:250. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 17. NHLBI. Clinical guidelines on the identification, evaluation, and treatment of overweight and obesity in adults: The evidence report. National institutes of health. Obes Res 1998;6 Suppl 2:51S-209. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 18. Asai Y, Tsutsui S, Oka H, Yoshimura N, Hashizume H, Yamada H, et al. Sagittal spino-pelvic alignment in adults: The Wakayama spine study. PloS One 2017;12:e0178697. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 19. Heuch I, Hagen K, Heuch I, Nygaard Ø, Zwart JA. The impact of body mass index on the prevalence of low back pain: The HUNT study. Spine 2015;40:497-504. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 20. Ashraf A, Farahangiz S, Jahromi BP, Setayeshpour N, Naseri M, Nasseri A. Correlation between radiologic sign of lumbar lordosis and functional status in patients with chronic mechanical low back pain. Asian Spine J 2014;8:565-70. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 21. Chun SW, Lim CY, Kim K, Hwang J, Chung SG. The relationships between low back pain and lumbar lordosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Spine J 2017;17:1180-91. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 22. Roussouly P, Gollogly S, Berthonnaud E, Dimnet J. Classification of the normal variation in the sagittal alignment of the human lumbar spine and pelvis in the standing position. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2005;30:346-53. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 23. Mirzashahi B, Hajializade M, Abdolahi Kordkandi S, Farahini H, Moghtadaei M, Yeganeh A, et al. Spinopelvic parameters as risk factors of nonspecific low back pain: A case-control study. Med J Islam Repub Iran 2023;37:61. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 24. Blandin C, Boisson M, Segretin F, Feydy A, Rannou F, Nguyen C. Pelvic parameters in patients with chronic low back pain and an active disc disease: A case-control study. Ann Phys Rehabil Med 2018;61:e155. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 25. Vialle R, Levassor N, Rillardon L, Templier A, Skalli W, Guigui P. Radiographic analysis of the sagittal alignment and balance of the spine in asymptomatic subjects. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2005;87:260-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 26. Zhou T, Salman D, McGregor AH. Recent clinical practice guidelines for the management of low back pain: A global comparison. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2024;25:344. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 27. Dang TH, Starke KR, Liebers F, Burr H, Seidler A, Hegewald J. Impact of sitting at work on musculoskeletal complaints of German workers-results from the study on mental health at work (S-MGA). J Occup Med Toxicol 2024;19:9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 28. Davidson JM, Callaghan JP. Do lumbar spine kinematics contribute to individual low back pain development in habitual sitting? Ergonomics 2005;April 3:1-14. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]