In selected Lichtman IIIc Kienböck’s disease with preserved lunate morphology and carpal alignment, a lunate-preserving approach – lunate osteosynthesis plus medial closing-wedge radial osteotomy – can achieve CT-confirmed union and acceptable early recovery, though its long-term durability versus palliative options (e.g., proximal row carpectomy or wrist arthrodesis) still requires validation in larger comparative studies.

Dr. Dos Santos Rocha Daniel, Department of Orthopedics, Cliniques Universitaires Saint-Luc, B-1200 Brussels, Belgium. E-mail: d.dossantos@student.uclouvain.be

Introduction: Kienböck’s disease is a rare and progressive osteonecrotic condition of the lunate that, in the absence of appropriate management, can result in irreversible structural deterioration of the wrist, collapse of the carpal architecture, and secondary osteoarthritis. Despite the existence of multiple therapeutic approaches, a standardized, evidence-based treatment algorithm has yet to be established. Treatment strategies are primarily determined by the salvageability of the lunate, which is classically considered viable when it preserves both its morphological integrity and structural continuity, in conjunction with a maintained carpal alignment. Several classification systems have been proposed that evaluate bone integrity, chondral damage, and lunate vascularity. In this context, Lichtman stage IIIc is defined by the presence of a coronal fracture of the lunate. This is a case report that documents the feasibility and structural healing in two carefully selected Lichtman IIIc Kienböck’s cases with preserved carpal alignment, which benefited from a more conservative surgical strategy.

Case Report: Two female patients, aged 42 and 47 years, with a history of chronic wrist pain, presented advanced Kienböck’s disease – Lichtman IIIc lesions, with acceptable carpal alignment and integrity of the shape of the lunate. Both cases were successfully treated using lunate osteosynthesis combined with medial closing wedge osteotomy of the radius, demonstrating the potential efficacy of this approach in selected patients.

Conclusion: In the advanced stages of Kienböck’s disease, when the lunate or the carpal architecture is compromised, palliative surgical interventions such as proximal row carpectomy or partial or total wrist arthrodesis are generally preferred. Through the presentation of these two advanced cases, we aim to highlight the possibility of adopting a conservative surgical approach to the lunate, provided that its morphology and the carpal architecture remain preserved. Within the limits of a case report, a lunate-preserving strategy – lunate osteosynthesis combined with medial closing wedge osteotomy of the radius – achieved computed tomography-confirmed union and acceptable early functional recovery in two selected Lichtman IIIc cases. Robust conclusions about durability and comparative benefit over established palliative procedures will require larger, prospective studies with longer follow-up.

Keywords: Kienböck’s disease, Lichtman IIIc stage, medial wedge osteotomy of the radius.

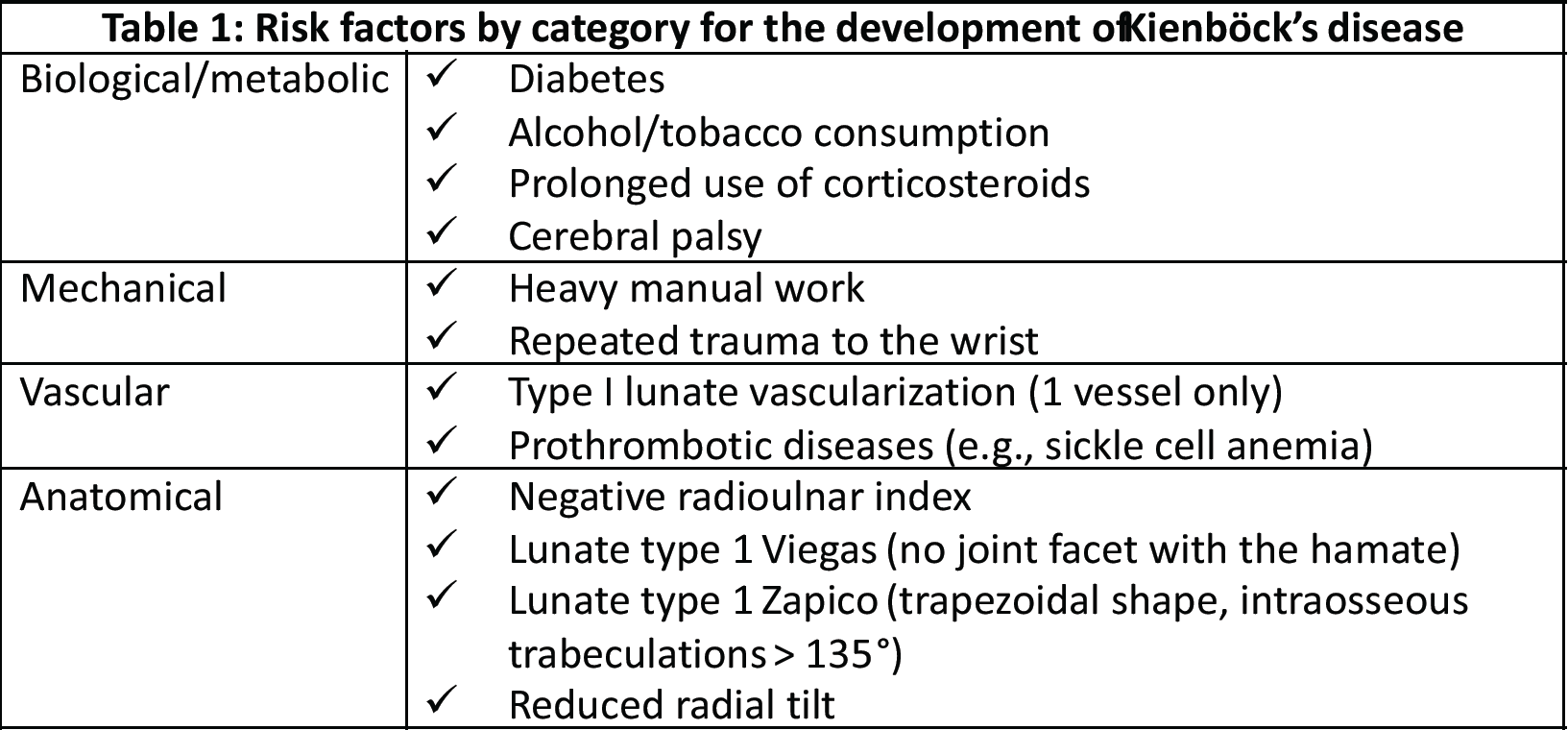

Kienböck’s disease is a pathological condition characterized by avascular necrosis of the lunate [1]. Historically, Robert Kienböck is credited with first describing this pathology in 1910, referring to it as a traumatic disease of the lunate or lunate malacia. However, the concept of lunate necrosis was only introduced several years later by Axhausen in 1924. The disease remains rare, and its etiology is not yet fully elucidated, with an estimated prevalence of approximately 0.27%, predominantly affecting young males between the ages of 20 and 40 [2]. Multiple factors contribute to the pathogenesis of Kienböck’s disease, encompassing mechanical, vascular, and biological/metabolic determinants (Table 1) [3].

Table 1: Risk factors by category for the development of Kienböck’s disease

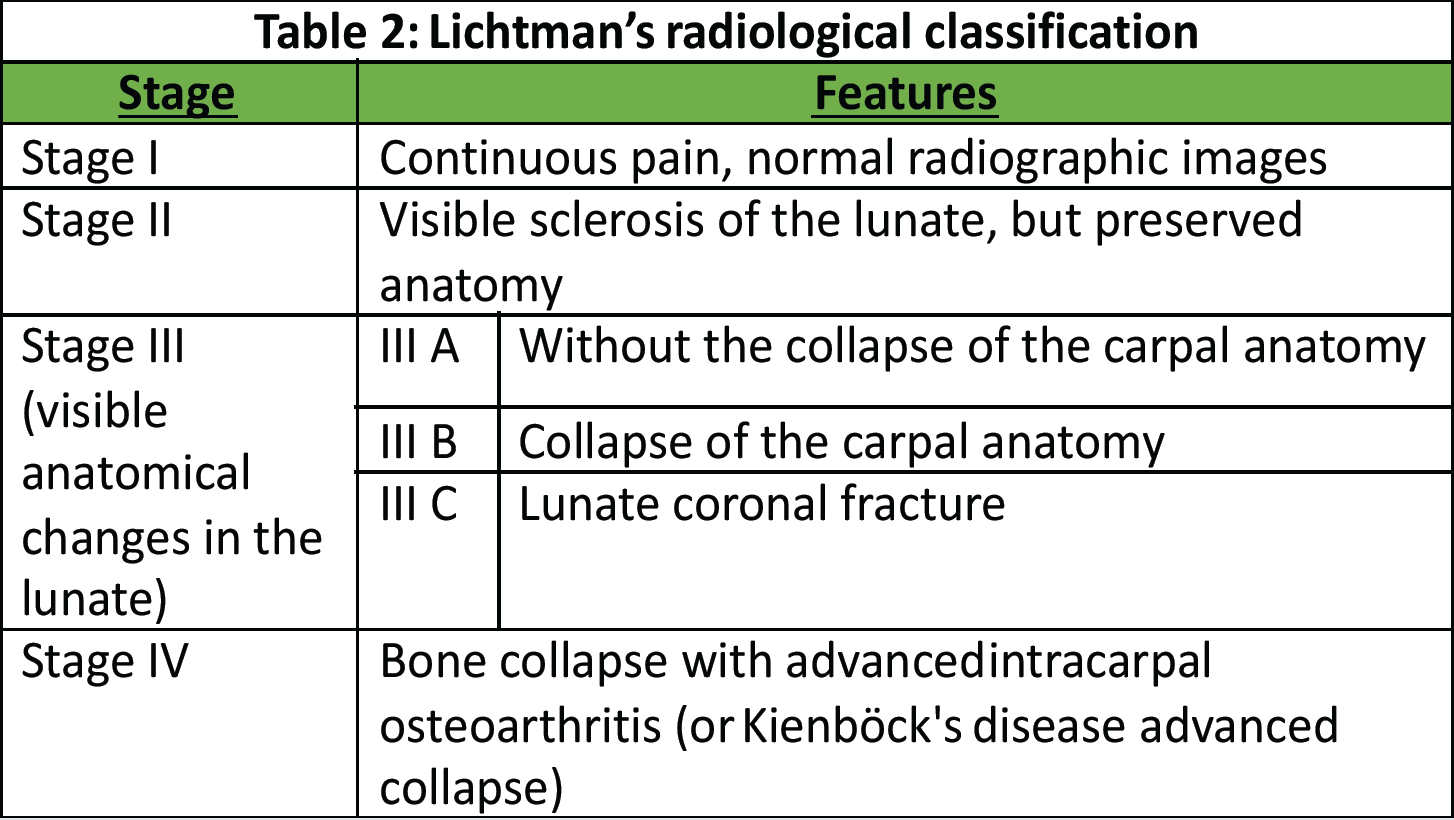

Disease progression can ultimately result in a lunate fracture and advanced bone degradation, leading to the collapse of the entire carpal architecture and the subsequent development of intracarpal osteoarthritis. Lichtman and Degnan [4] proposed a radiographic classification system delineating four principal stages based on the extent of lunate and carpal degeneration (Table 2).

Table 2: Lichtman’s radiological classification

More recently, additional classification systems have emerged to refine disease staging. Schmitt [5] introduced a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)-based classification that stratifies disease progression according to vascular compromise, whereas Bain and Begg [6] proposed an arthroscopy-based classification evaluating the state of the articular cartilage. However, the correlation between these different classification systems and the array of available therapeutic options remains a subject of ongoing debate, with no established consensus. In clinical practice, a pragmatic approach often distinguishes two primary scenarios based on the integrity of the lunate and the overall carpal architecture [7]. According to Lichtman’s classification, stage IIIc is defined by the presence of a coronal fracture of the lunate. Given the structural compromise, palliative treatment options are commonly favored [8]. Nevertheless, in cases where the lunate retains its overall morphology without evidence of collapse, osteosynthesis may be a viable therapeutic strategy [9], particularly when combined with an adjunctive procedure aimed at promoting lunate revascularization, for example, a radius shortening osteotomy. Although the precise mechanisms underlying the healing of lunate necrosis following radial shortening osteotomy remain incompletely understood, several hypotheses have been proposed. These include hypervascularization induced by the osteotomy-related fracture and a reduction in mechanical stresses and constraints [10]. Regardless of the exact process, a significant improvement in clinical symptoms has been consistently reported [11]. Consequently, various osteotomy techniques featuring distinct cutting profiles have been developed to optimize therapeutic outcomes.

Here, we present two cases of Kienböck’s disease classified as Lichtman stage IIIc, characterized by complete osteonecrosis and a coronal fracture of the lunate, without associated cartilage damage. Both patients underwent a medial closing wedge osteotomy of the radius combined with compression screw fixation of the lunate fracture. The two patients were female, aged 42 and 47 years, with a history of wrist pain. Pre-operative imaging included standard wrist radiography, which revealed a negative ulnar variance (radiographic ulnar index), computed tomography (CT) confirming the presence of a lunate fracture, and MRI demonstrating osteonecrosis (showing a hypointense signal on T1-weighted sequences and a hyperintense signal on T2-weighted sequences, with no gadolinium enhancement). No signs of carpal instability or cartilage degeneration were observed in the surrounding structures.

- Patient A: A 42-year-old right-handed housewife presented with significant pain and stiffness in her dominant wrist persisting for 4 months. She had no history of trauma and was a non-smoker. Her medical history was notable for diabetes and a prior episode of deep vein thrombosis in the lower limb several years earlier (Fig. 1, 2, 3).

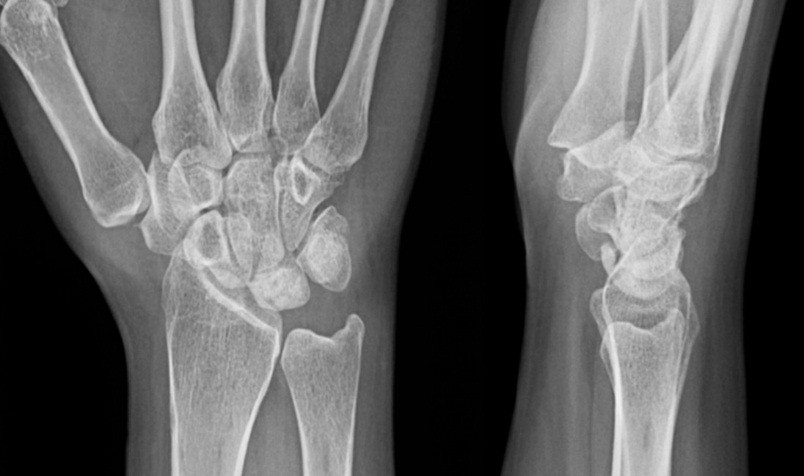

Figure 1: X-ray radiographic ulnar index of −3 mm.

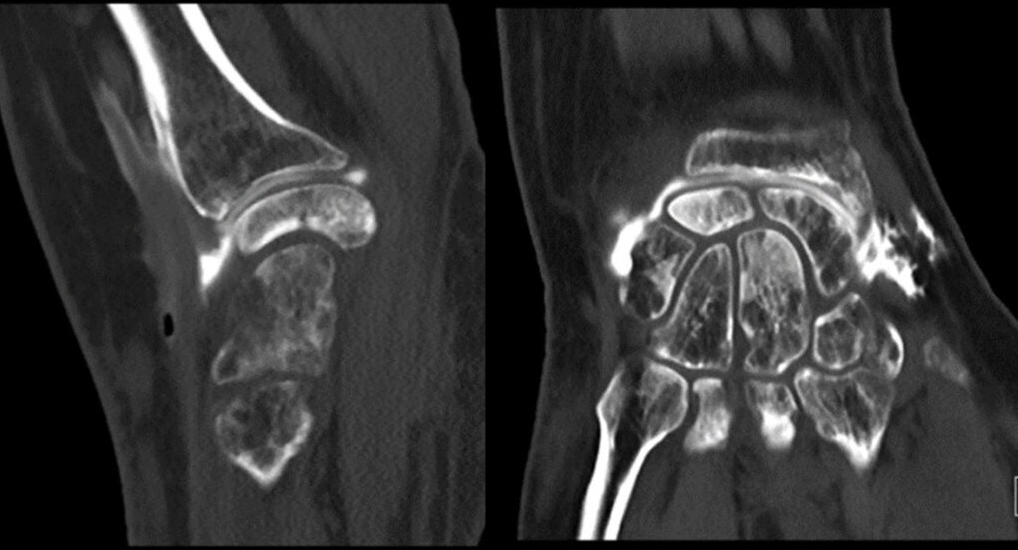

Figure 2: Computed tomography scan.

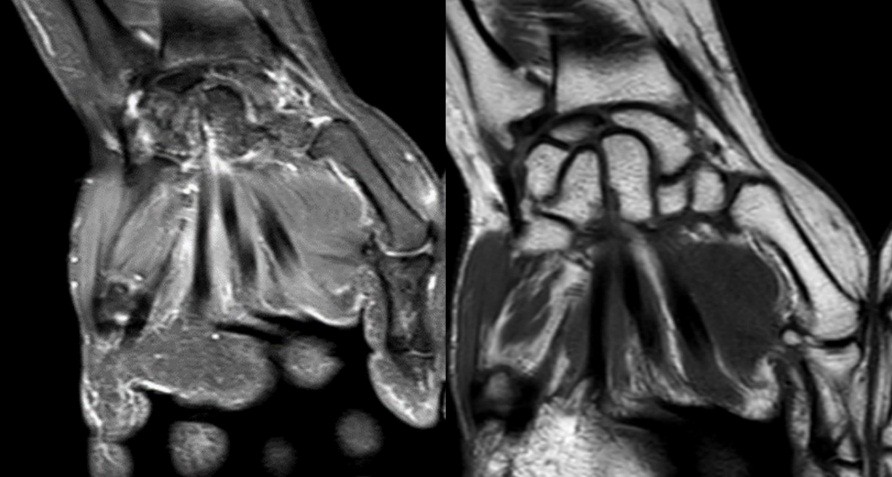

Figure 3: Magnetic resonance imaging.

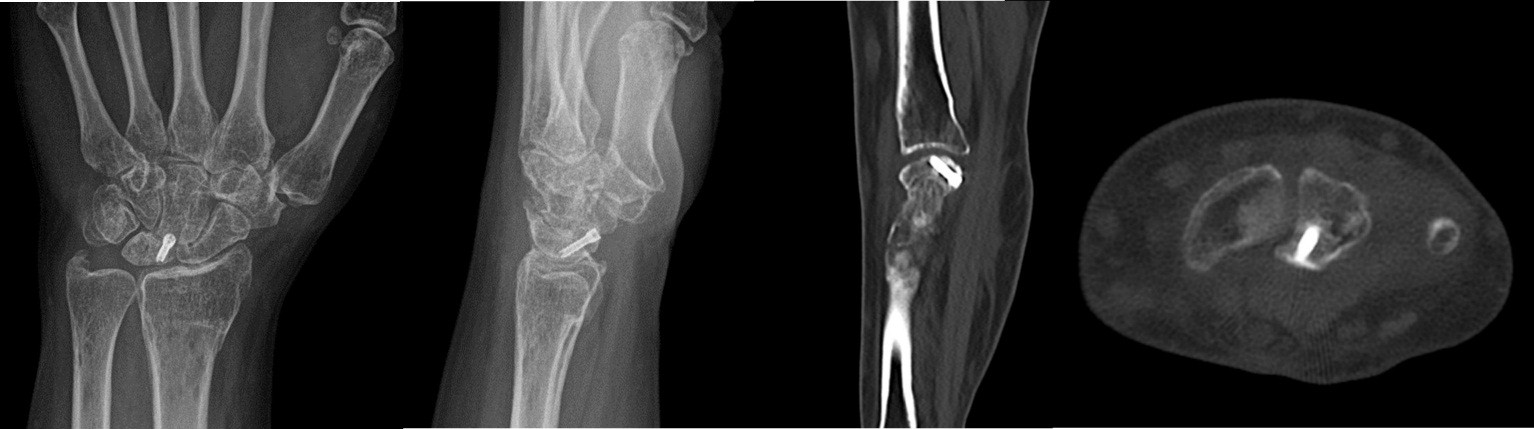

- Patient B: A 47-year-old left-handed housewife presented with a 1-year history of left wrist pain. She reported no history of trauma, was a non-smoker, and had no significant medical history (Fig. 4, 5, 6).

Figure 4: X-ray radiographic ulnar index of −3.7 mm.

Figure 5: Computed tomography scan.

Figure 6: Magnetic resonance imaging.

Surgical technique

Both patients were positioned in the supine position, and a tourniquet was inflated to 250 mmHg at the start of the procedure. The surgical technique involved a closing wedge osteotomy of the radius combined with compression screw fixation to stabilize the lunate fracture. For osteotomy stabilization, a T-plate was applied to the distal radius: a palmar approach following Henry’s technique was used for Patient A, whereas a dorsal approach centered on the third ray was employed for Patient B. The lunate fracture was stabilized using a cannulated compression screw: A SpeedTip 2.2 mm Medartis screw (Fig. 7) for Patient A and an HCS 2.4 mm compression screw (Fig. 8) for Patient B.

Figure 7: Patient A – post surgery.

Figure 8: Patient B – post surgery.

The posterior interosseous nerve was identified, and a resection of one of its terminal branches, approximately 1 cm in length, was performed in both patients. The wrist was immobilised in a short-arm cast for 6 weeks, followed by 4 weeks of supervised physiotherapy with a protective wrist splint. Therapy sequence: Edema control and scar management upon cast removal; progressive passive then active range‑of‑motion exercises; proprioceptive work from week 8; and gradual strengthening beginning around week 10. Return to activities of daily living was staged, with avoidance of forceful grasping and impact until painless functional arcs were achieved.

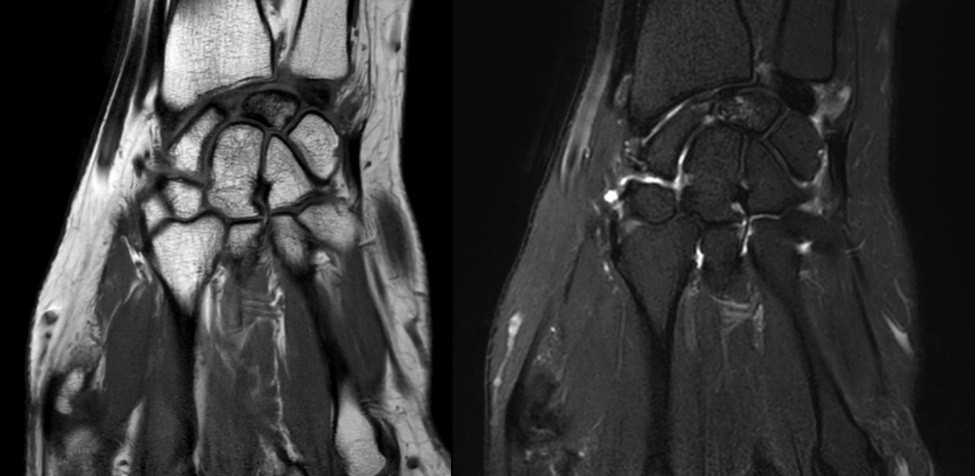

The mean follow-up duration was 24 months (Patient A: 36 months and Patient B: 12 months). Bone consolidation of the radial osteotomy was achieved on average 3 months postoperatively for both patients, while consolidation of the lunate fracture occurred at 6 months for Patient A (Fig. 9) and at 7 months for Patient B (Fig. 10). Lunate fracture union and radial osteotomy union were assessed with CT.

Figure 9: Patient A – X-ray and computed tomography scan: radius/ lunate consolidation.

Figure 10: Patient B X-ray and computed tomography scan: radius/ lunate consolidation.

CT was chosen because it is widely regarded as more reliable than radiographs for assessing carpal bone union and arthrodesis/osteotomy healing, and is appropriate when the clinical course is favorable. Routine post-operative perfusion studies were not pursued because the clinical evolution was satisfactory, and structural union had been demonstrated on CT.

The distal radius plate was removed due to discomfort at 13 months for Patient A and at 3 months for Patient B.

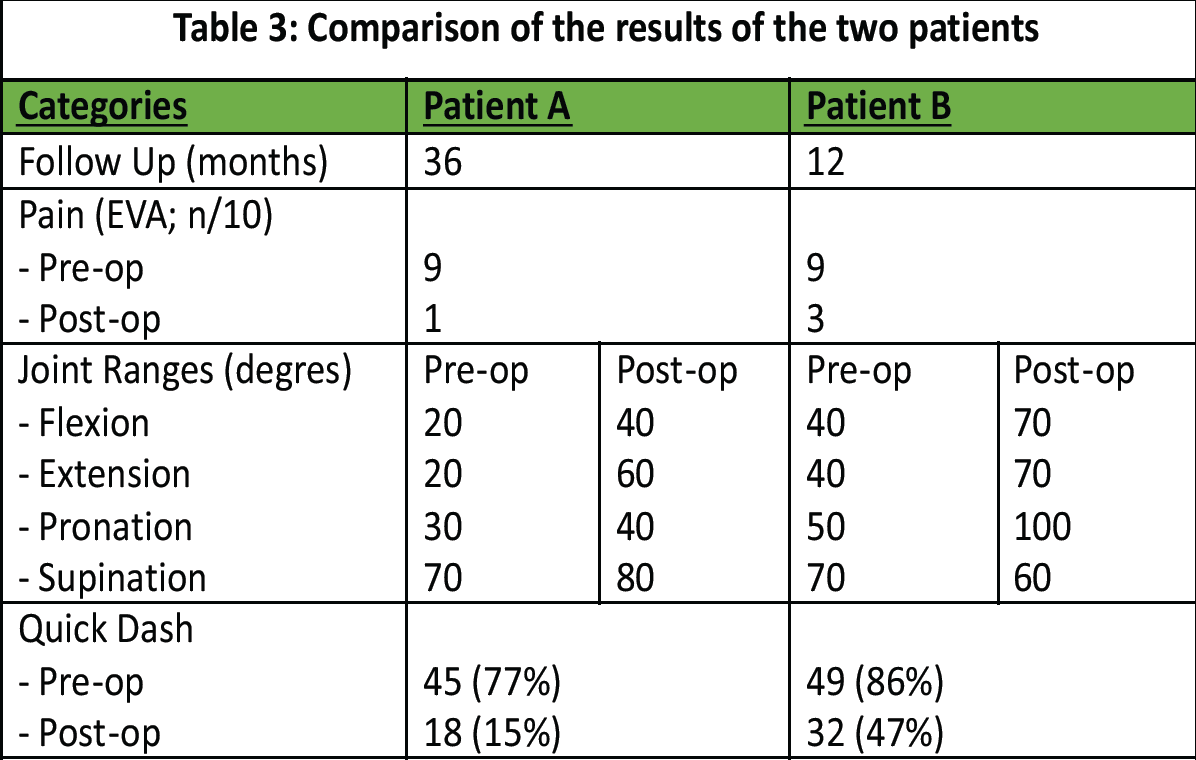

The parameters assessed during the follow-up are listed in Table 3: Pain, range of motion (before and after the operation), and the score of the QuickDash questionnaire completed by the patients.

Table 3: Comparison of the results of the two patients

- Pain (EVA score)

- Relatively significant improvement in pain after surgery. Both patients, during the follow-up, reported intermittent mild pain, less than once a day.

- Joint range of motion (degrees)

- Functional improvement was observed in both patients.

- QuickDash score: Degree of disability in everyday life (0% = no disability/100% = maximum disability)

- Significant reduction in daily difficulty with commonly performed daily movements and activities.

The treatment of Kienböck’s disease remains an area of ongoing study and evolution. Treatment strategies are often tailored based on the integrity of the lunate and the preservation of the carpal architecture [12]. When these structures are preserved, conservative treatment options for the lunate are typically preferred, including:

- Casting immobilization;

- Unloading procedures, such as lunate decompression – when a negative ulnar variance and/or abnormal radial inclination is present, radial shortening osteotomy may be performed; if a neutral or positive ulnar variance is present, capitate shortening osteotomy may be considered;

- Lunate decompression via arthroscopic forage;

- Revascularization procedures, which may involve direct revascularization of the lunate using either a pedicled or free vascularized bone graft.

In cases where the lunate or carpal architecture is compromised, palliative surgical interventions are generally recommended, including:

- Lunate replacement with materials such as silicone, autogenous tendon, metallic spheres, or the pisiform;

- Proximal row carpectomy (PRC);

- Partial or total wrist arthrodesis.

Despite various treatment options, the exact mechanism facilitating the lunate healing remains uncertain. Current theories suggest that the inflammatory and angiogenic responses triggered by surgical interventions may play a critical role in promoting lunate revascularization [13]. This could help explain why various surgical procedures, despite differing approaches, can yield positive results. Indirect revascularization of the lunate has even been observed after non-revascularization-related procedures, such as metaphyseal core decompression [14]. In our study, only patients with preserved carpal alignment and maintained lunate morphology were considered for a lunate‑preserving strategy (lunate osteosynthesis plus radial osteotomy). This intentional selection aligns with decision frameworks that typically reserve palliative procedures (e.g., PRC or partial/total arthrodesis) for this type of case. In the two cases presented, a closing wedge osteotomy of the radius was chosen due to its dual benefit: not only does it stimulate the inflammatory response that may aid in revascularization, but it also reduces stress and mechanical constraints on the lunate [15], which had been weakened by the fracture. At the same time, we had a non-displaced coronal fracture of the lunate, without alteration of the lunate shape that needed some kind of stabilization to prevent further destruction of the lunate and to promote the fracture healing. With this in mind, we tried to achieve both goals by combining the radial osteotomy with stabilization of the fracture by local screw compression, without any kind of accessory graft.

Study limitations

This case report is limited by its design: Two patients treated at a single center by a single team, no control group, and a follow-up of 12–36 months. These factors restrict generalizability and prevent firm conclusions about comparative efficacy or long-term durability (e.g., late collapse, recurrent pain, and degenerative arthritis). In addition, selecting only patients with preserved carpal alignment and lunate morphology introduces selection bias. Accordingly, our findings are hypothesis-generating and intended to inform the design of larger, prospective comparative studies. In the follow-up, the grip strength and broader quality-of-life instruments were not systematically collected and are a limitation to be addressed in future work.

In presenting these two advanced cases, we aim to highlight the possibility of opting for a surgical approach that conserves the lunate, provided the overall shape of the lunate remains intact and the carpal architecture is preserved. In these cases, we utilized a medial closing wedge osteotomy of the radius combined with compression screw fixation. We hope that our approach has been successful in halting further damage to the carpal architecture. However, to fully assess this, it is necessary to continue monitoring these patients, as carpal osteoarthritis may take several years to manifest. Given the lack of substantial evidence, further comparative studies are essential to validate and compare the efficacy of the various surgical techniques available, particularly in the advanced stages of Kienböck’s disease.

In advanced Kienböck’s disease, palliative surgical procedures are generally preferred. Within the constraints of a case report, lunate‑preserving osteosynthesis combined with radial osteotomy achieved structural union on CT and acceptable early functional recovery in two selected Lichtman IIIc cases. Definitive statements about durability and relative benefit versus established palliative procedures require larger, comparative studies with longer follow‑up.

References

- 1. Lutsky K, Beredjiklian PK. Kienböck disease. J Hand Surg Am 2012;37:1942-52. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 2. Daly CA, Graf AR. Kienböck disease: Clinical presentation, epidemiology, and historical perspective. Hand Clin 2022;38:385-92. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 3. Bain GI, MacLean SB, Yeo CJ, Perilli E, Lichtman DM. The etiology and pathogenesis of Kienböck disease. J Wrist Surg 2016;5:248-54. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 4. Lichtman DM, Degnan GG. Staging and its use in the determination of treatment modalities for Kienböck’s disease. Hand Clin 1993;9:409-16. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 5. Schmitt R, Kalb KH. Imaging in Kienböck’s disease. Handchir Mikrochir Plast Chir. 2010;42(3):162e170. doi:10.1055/s-0030-1253433. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

- 6. Bain GI, Begg M. Arthroscopic assessment and classification of Kienbock’s disease. Tech Hand Up Extrem Surg 2006;10:8-13. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 7. Lichtman DM, Pientka WF 2nd, Bain GI. Kienböck disease: A new algorithm for the 21st Century. J Wrist Surg 2017;6:2-10. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 8. Camus EJ, Van Overstraeten L. Kienbock’s disease in 2021. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res 2022;108(1 Suppl):103161. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 9. Chou J, Bacle G, Ek ET, Tham SK. Fixation of the fractured lunate in Kienböck disease. J Hand Surg Am 2019;44:67.e1-67.8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 10. Nakamura R, Nakao E, Nishizuka T, Takahashi S, Koh S. Radial osteotomy for Kienböck disease. Tech Hand Up Extrem Surg 2011;15:48-54. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 11. Shin YH, Kim JK, Han M, Lee TK, Yoon JO. Comparison of long-term outcomes of radial osteotomy and nonoperative treatment for Kienbock disease: A systematic review. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2018;100:1231-24. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 12. Tee R, Butler S, Ek ET, Tham SK. Simplifying the decision-making process in the treatment of Kienböck’s disease. J Wrist Surg 2024;13:294-301. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 13. Chojnowski K, Opiełka M, Piotrowicz M, Sobocki BK, Napora J, Dąbrowski F, et al. Recent advances in assessment and treatment in Kienböck’s disease. J Clin Med 2022;11:664. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 14. Afshar A. Lunate revascularization after capitate shortening osteotomy in Kienböck’s disease. J Hand Surg Am 2010;35:1943-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 15. Camus EJ, Van Overstraeten L, Schuind F. Lunate biomechanics: Application to Kienbock’s disease and its treatment. Hand Surg Rehabil 2021;40:117-25. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]