Multiple myeloma can rarely present as cauda equina syndrome caused by isolated vertebral collapse; early recognition and multidisciplinary intervention are essential for optimal neurological and oncological outcomes.

Dr. Vimal Prakash, Department of Orthopaedics, All India institute of medical sciences, Jodhpur, Rajasthan, India. E-mail: vimalprakash.1995@gmail.com

Introduction: Multiple myeloma (MM) is a malignant plasma cell disorder commonly affecting the axial skeleton, with vertebral compression fractures frequently observed. However, isolated lumbosacral vertebral collapse leading to acute cauda equina syndrome (CES) as the first clinical manifestation is extremely rare. This case highlights the importance of suspecting underlying malignancy in elderly patients presenting with acute spinal cord compression without trauma or systemic symptoms.

Case Report: A woman in her late 60s presented with acute lower limb weakness, urinary incontinence, and constipation. Examination revealed sensory deficits below L5, reduced motor strength in foot muscles, and an absent bulbocavernosus reflex, consistent with CES. Imaging showed L5 vertebral collapse with canal compromise. Magnetic resonance imaging suggested a pathological fracture, and positron emission tomography-computed tomography confirmed a solitary lesion. Serum protein electrophoresis showed M-protein, and histopathology confirmed MM. The patient underwent posterior decompression and instrumentation followed by bisphosphonate therapy and local radiation. At 1-year follow-up, she regained full neurological function and resumed normal activities.

Conclusion: Isolated vertebral involvement in MM may rarely present as CES and should be considered in elderly patients with acute spinal syndromes, even in the absence of systemic signs. Prompt diagnosis, surgical decompression, and targeted therapy can lead to excellent recovery. This case underscores the value of multidisciplinary care and raises awareness of atypical spinal presentations of MM.

Keywords: Multiple myeloma, cauda equina syndrome, vertebral collapse, plasma cell neoplasm, pathological fracture.

Multiple myeloma (MM) is a malignant plasma cell neoplasm characterized by clonal proliferation within the bone marrow, commonly presenting with anemia, hypercalcemia, renal impairment, and bone pain secondary to osteolytic lesions [1]. Skeletal involvement is seen in most patients, with vertebral compression fractures occurring in up to 60–80% of cases, typically involving the thoracic and thoracolumbar spine [2,3]. However, vertebral collapse leading to acute neurological deficits such as cauda equina syndrome (CES) is exceedingly rare, particularly as the initial manifestation [4]. CES is a medical emergency defined by the constellation of lower limb motor and sensory deficits, saddle anesthesia, and autonomic dysfunction affecting bowel or bladder control [5]. Common etiologies include massive lumbar disc herniation, trauma, metastatic disease, and infections [6]. Although spinal involvement is not uncommon in MM, CES resulting directly from pathological vertebral collapse due to MM is rare and sparsely reported in the literature [7,8]. Here, we describe a rare case of an elderly female presenting with acute CES as the first clinical sign of MM, without preceding trauma or typical systemic features. The case highlights the importance of early suspicion for malignancy in elderly patients presenting with acute spinal cord compression syndromes and emphasizes the need for timely multidisciplinary intervention.

History and examination

A female in her late 60s presented to the emergency department with complaints of sudden and severe worsening of lower back pain over the past week, followed by bilateral lower limb weakness, urinary incontinence, and constipation over the preceding 2 days. Notably, there was no history of recent trauma, strenuous activity, or fever. She had reported mild, non-disabling back pain for the past 6 months, which she had neglected, as it did not interfere with her daily activities. Her past medical history was significant only for hypertension, which was well-controlled on regular medication. There was no known history of malignancy, metabolic bone disease, or prior spinal issues. This presentation was alarming due to the rapid neurological deterioration and onset of bladder and bowel dysfunction, strongly indicative of an acute compressive pathology causing CES. On clinical examination, the patient exhibited tenderness over the lower lumbar and sacral spine. Neurological evaluation revealed reduced sensation below bilateral L5 dermatomes, along with decreased motor power in toe extension and foot plantar flexion bilaterally. Per rectal examination showed absent bulbocavernosus reflex, decreased anal tone, and loss of perianal sensation and voluntary anal contraction—findings consistent with CES.

Investigations

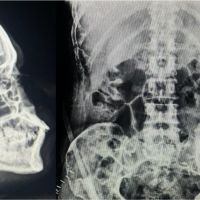

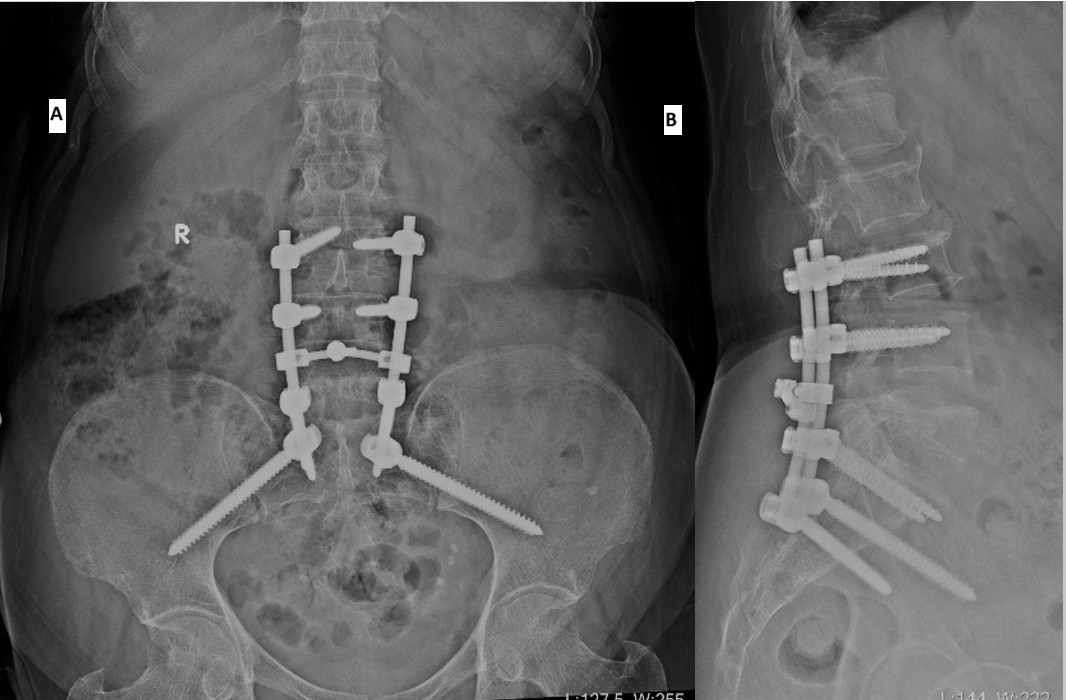

Plain X-rays of the lumbosacral spine showed collapse and loss of height of the L5 vertebral body (Fig. 1).

Figure 1: Plain radiographs anteroposterior (a) and Lateral (b) projections showing collapse of L5 vertebrae (marked with arrow).

Computed tomography revealed collapse of the L5 vertebral body with retropulsion of bony fragments into the spinal canal (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: Non contrast computed tomography scan images showing collapse of the L5 vertebra causing severe narrowing of spinal canal (a) Axial, (b) Coronal, (c) sagittal cuts.

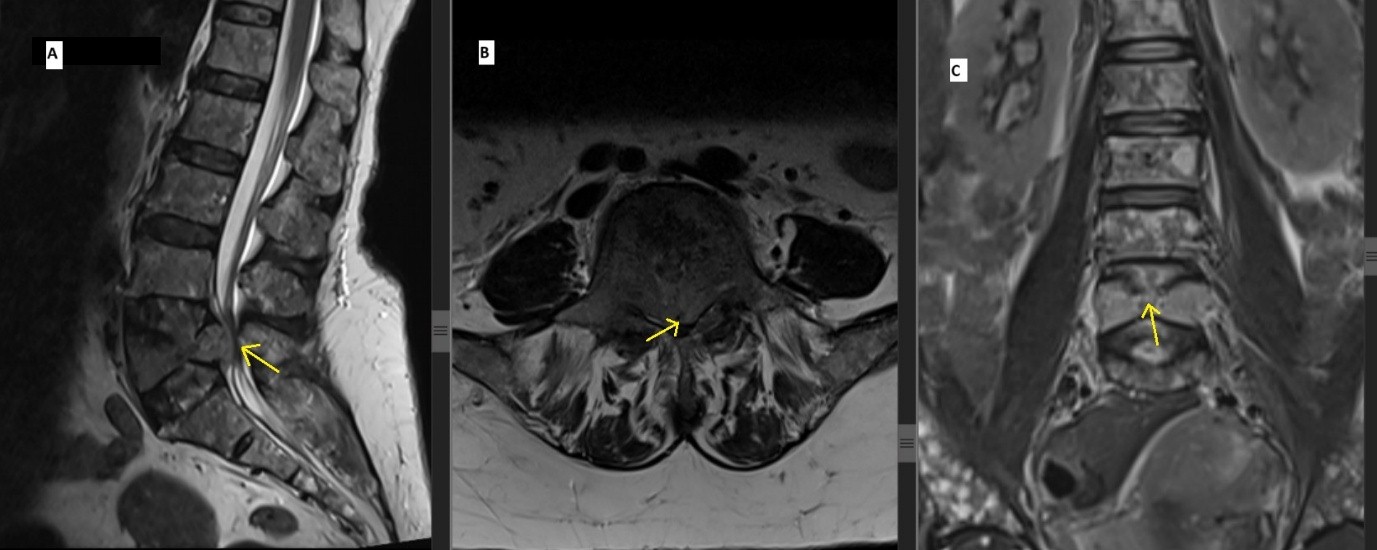

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the spine demonstrated altered heterogeneous signal intensity involving the marrow and a compression fracture L5, with reduced vertebral height was causing significant spinal canal stenosis and cauda equina compression. These findings were suggestive of a pathological fracture due to MM (Fig. 3).

Figure 3: Magnetic resonant images showing L5 vertebral compression fracture with decreased vertebral height is seen causing significant stenosis of spinal canal and compression of cauda equina (a) Sagital T2 weighted image, (b) Axial T2 weighted image, (c) Coronal T2 weighted image).

Laboratory tests

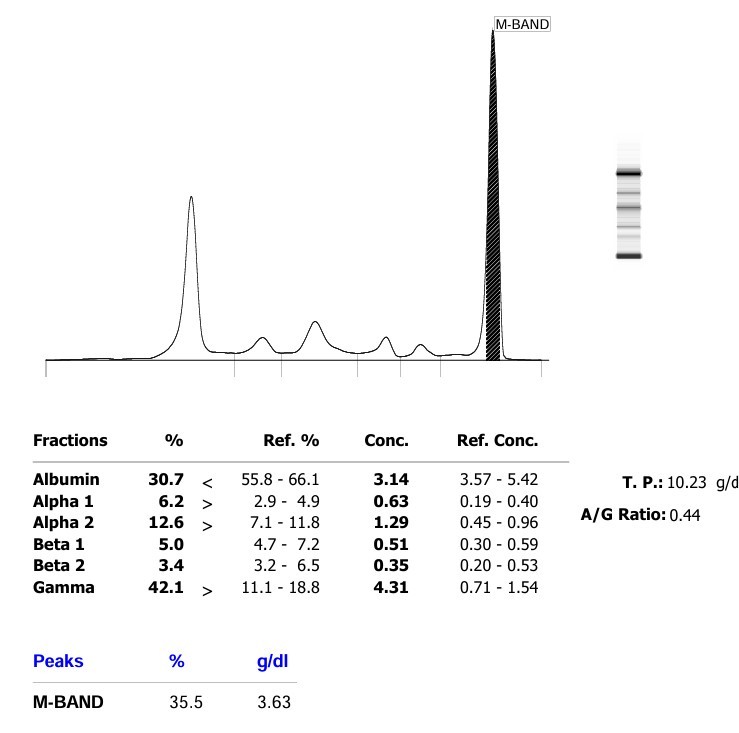

Laboratory evaluation revealed elevated beta-2 macroglobulin levels, increased serum immunoglobulin G (IgG), and reduced serum immunoglobulin A (IgA) and immunoglobulin M (IgM). Serum protein electrophoresis showed increased total serum protein, a reversed albumin-to-globulin ratio, and the presence of an M-protein band, which was consistent with the diagnosis of MM (Fig. 4).

Figure 4: Serum protein electrophoresis showing monoclonal M band.

Positron emission tomography revealed an FDG-avid lytic-sclerotic lesion with partial collapse of the L5 vertebra. No abnormal hypermetabolic lesions were detected elsewhere in the body.

Treatment

A multidisciplinary tumor board, including specialists from orthopedics, pathology, oncology, and radiology, reviewed the case and recommended surgical decompression of the spinal cord. The patient underwent posterior decompression at L5, pedicle screw fixation at L3, L4, S1, and iliac screw fixation at S2 level. She tolerated the procedure well, and her post-operative course was uneventful. Intravenous zoledronic acid was administered in the post-operative period. Wound inspection during follow-up revealed a clean and healthy surgical site (Fig. 5).

Figure 5: Post-operative radiographs (a) anteroposterior, (b) lateral views.

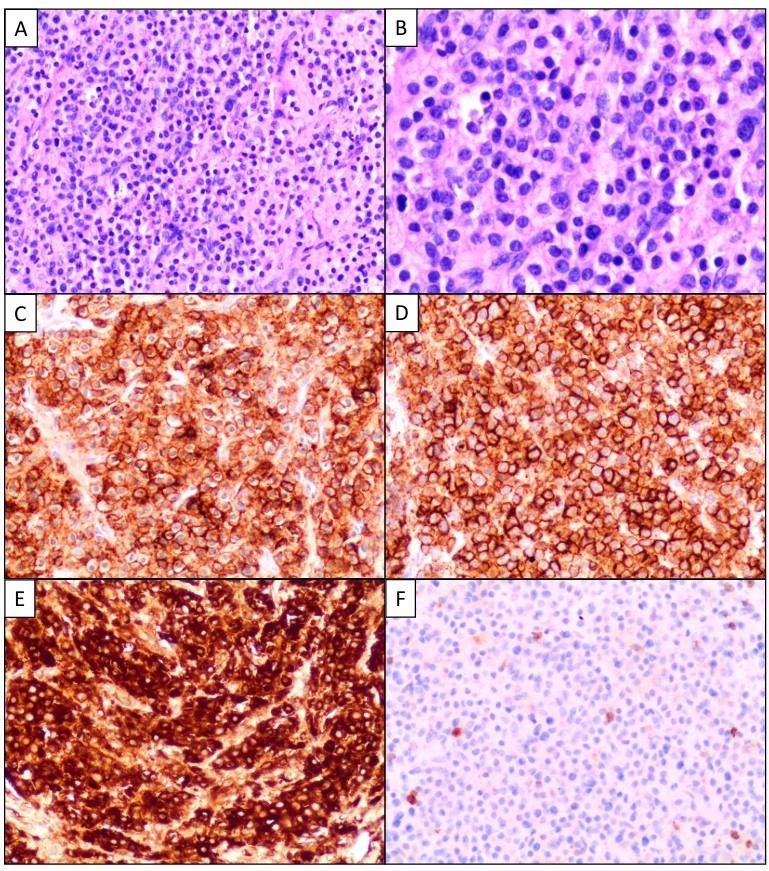

Histopathological examination of intraoperative tissue samples showed fibrocollagenous and fibro-adipose tissue with necrotic bony fragments infiltrated by sheets of plasma cells. Immunohistochemistry revealed that the plasma cells were positive for CD38, CD138, MUM1, and CD56, and showed lambda light chain restriction. The cells were negative for CD45, confirming a diagnosis of MM. Given the isolated nature of the lesion confined to the L5 vertebra with no evidence of systemic disease on positron emission tomography-computed tomography (PET-CT), the patient subsequently underwent local radiation therapy to the L5 region (Fig. 6).

Figure 6: (a) Microscopic image showing sheets of atypical plasma cells (Hematoxylin and Eosin [H & E], ×200). (b) Higher magnification displaying atypical plasma cells with enlarged nuclei, dispersed chromatin, and conspicuous nucleoli (H & E, ×400). Immunohistochemistry (c, d, e, f, ×200): Sheets of plasma cells showing diffuse expression of CD38 (c) and CD138 (d), with lambda light chain restriction (e) lambda, (f) kappa.

Neurological status remained unchanged immediately after surgery and radiation therapy. Over time, she showed progressive neurological recovery. At 1-year follow-up, she had regained bowel and bladder control and demonstrated 5/5 strength in ankle and toe movements bilaterally. She was independently ambulatory and resumed her routine daily activities (Fig. 7).

Figure 7: Patient at 1 year follow up, able to walk and do all her routine daily activities.

MM is a systemic plasma cell neoplasm with a median age at diagnosis of 66 years and frequently presents with constitutional symptoms, anemia, renal dysfunction, and lytic bone lesions [1]. Although vertebral involvement is common, the thoracic and thoracolumbar spine is more frequently affected, with isolated lumbosacral involvement being relatively uncommon [2,3,9]. The presentation of MM as CES is rare and poorly documented, particularly when CES is the sole or initial manifestation [4,7]. CES is a time-sensitive neurological emergency, and prompt diagnosis is critical to minimize the risk of irreversible deficits [5,10]. In our case, the patient presented with an acute onset of bladder dysfunction, bilateral lower limb weakness, and saddle anesthesia – features strongly indicative of CES. However, the absence of any history of trauma, systemic features, or known malignancy posed a diagnostic challenge, delaying consideration of a neoplastic cause. Radiologically, the L5 vertebral collapse with retropulsion of bony fragments into the spinal canal was evident on computed tomography and MRI. The imaging also revealed heterogeneous marrow signal changes in the vertebrae, raising suspicion for a marrow infiltrative process [10,11]. Though MM frequently causes vertebral compression fractures, solitary involvement of L5 leading to CES is extremely rare [9]. Laboratory studies demonstrated classical features of MM: Elevated serum IgG levels, decreased IgA and IgM, reversed albumin-to-globulin ratio, and a monoclonal M-protein spike on serum electrophoresis [12]. PET-CT further confirmed a focal lesion without other systemic skeletal involvement, underscoring the rarity and focal nature of this presentation [13]. Histopathological examination was crucial in confirming the diagnosis. The neoplastic plasma cells were positive for CD38, CD138, MUM1, and CD56 with lambda light chain restriction, while negative for CD45 – features consistent with MM [14]. These immunophenotypic markers not only establish the diagnosis but also have prognostic relevance [14]. Urgent surgical decompression remains the cornerstone of CES management. Literature suggests that outcomes are significantly improved when decompression is performed within 48 h of symptom onset [15]. Although our patient underwent surgery beyond this window, she demonstrated gradual but significant recovery over time, eventually regaining autonomy in daily activities. Following surgery, the patient was treated with intravenous bisphosphonates and local radiation therapy according to the standard of care for MM [16]. Her neurological recovery and absence of systemic disease progression over a year of follow-up underline the importance of multidisciplinary management in such complex and rare presentations. This case is unique due to the isolated L5 collapse as the first and only clinical sign of MM leading to CES – an association rarely described in literature. Such presentations highlight the necessity of maintaining a high index of suspicion for occult malignancy in elderly patients with acute spinal syndromes, even in the absence of trauma or systemic illness [4,7,16].

CES as the initial manifestation of MM is extremely rare and diagnostically challenging, particularly in the absence of systemic features. This case emphasizes the importance of maintaining high suspicion for malignancy in elderly patients presenting with acute neurological deficits without trauma. Timely imaging, surgical decompression, and pathological confirmation are crucial for neurological recovery and oncologic control. Multidisciplinary management, including surgery, radiotherapy, and bisphosphonate therapy, can result in significant functional restoration. Awareness of such atypical presentations ensures early diagnosis, timely intervention, and improved patient outcomes in rare spinal manifestations of MM.

Isolated vertebral collapse causing CES may be the first sign of MM. Clinicians should consider malignancy in elderly patients with acute spinal compression symptoms, even without systemic features, and initiate timely imaging and multidisciplinary management to ensure neurological recovery and disease control.

References

- 1. Kyle RA, Rajkumar SV. Multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med 2004;351:1860-73. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 2. Palumbo A, Anderson KC. Multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med 2011;364:1046-60. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 3. Rosiñol L, Cibeira MT, Bladé J. Bone disease in multiple myeloma. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am 2007;21:1115-45. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 4. Isern N, Oró J, Filella X. Cauda equina syndrome as the first manifestation of multiple myeloma. Eur Spine J 2005;14:579-82. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 5. Fraser S, Roberts L, Murphy E. Cauda equina syndrome: A literature review of its definition and clinical presentation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2009;90:1964-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 6. Gokaslan ZL, York JE, Walsh GL Cauda equina syndrome: A review of 44 cases. Neurosurgery 1997;40:103-10. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 7. Gardner A, Gardner E, Morley T. Cauda equina syndrome: A review of the current clinical and medico-legal position. Eur Spine J 2011;20:690-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 8. Morgan GJ, Davies FE, Linet M. Myeloma: Disease biology and epidemiology. Hematol Am Soc Hematol Educ Program 2003;2003:339-57. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 9. Abdi S, Wei SY, Yang B. Vertebral compression fractures: A review. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2005;84:878-84. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 10. Dimopoulos MA, Terpos E. Imaging in multiple myeloma. Curr Hematol Malig Rep 2010;5:90-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 11. Rajkumar SV. Multiple myeloma: 2020 update on diagnosis, risk‐stratification and management. Am J Hematol 2020;95:548-67. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 12. Cavo M, Terpos E, Nanni C. Role of 18F-FDG PET/CT in the diagnosis and management of multiple myeloma and other plasma cell disorders. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2011;38:1145-58. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 13. Chang H, Qi XY, Trieu Y. CD56 expression predicts clinical outcome in patients with multiple myeloma treated with high-dose chemotherapy and stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant 2006;38:449-54. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 14. Ahn UM, Ahn NU, Buchowski JM, Garrett ES, Sieber AN, Kostuik JP. Cauda equina syndrome secondary to lumbar disc herniation: A meta-analysis of surgical outcomes. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2000;25:1515-22. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 15. Terpos E, Morgan G, Dimopoulos MA, Drake MT, Lentzsch S, Raje N, et al. International myeloma working group recommendations for the treatment of multiple myeloma-related bone disease. J Clin Oncol 2013;31:2347-57. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 16. Güler O, Mutlu S, Sariyilmaz K. An unusual cause of cauda equina syndrome: Solitary bone plasmacytoma. Spine J 2015;15:e13-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]