Shoulder arthroplasty in patients with osteogenesis imperfecta should be performed with full knowledge of possible complications.

Dr. Edward G McFarland, Division of Shoulder and Elbow Surgery, Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Maryland, USA. E-mail: emcfarl1@jhmi.edu

Introduction: Reverse total shoulder arthroplasty (RTSA) has many indications, including acute proximal humerus fracture or nonunion of such a fracture. However, we are unaware of any reports of the use of RTSA to treat proximal humerus fractures in patients with osteogenesis imperfecta (OI).

Case Report: Here, we describe the challenges of RTSA for fracture nonunion in a 67-year-old woman with OI. The humeral component of the prosthesis loosened, and aspiration revealed 2 organisms. She underwent placement of an antibiotic spacer, after which cultures were negative. A second revision was then performed, during which a cemented proximal humeral component was implanted as part of the RTSA system. Subsequently, she fell, fracturing the humerus, which was treated with internal fixation with plates reinforced with a fibular allograft. The RTSA humeral component subsequently loosened, and she was revised to an allograft prosthetic composite. She subsequently healed but died after a fall in her home.

Conclusion: Prompt identification and management of complications are crucial for improving outcomes of RTSA in patients with OI.

Keywords: Allograft prosthetic composites, complications, fracture nonunion, osteogenesis imperfecta, reverse total shoulder arthroplasty.

Osteogenesis imperfecta (OI), also known as “brittle bone disease,” is a rare genetic disorder caused by abnormalities in type 1 collagen synthesis and affects approximately 1 in 15,000–20,000 births [1,2]. OI is classified by clinical severity and genotype, with present nosology based on the original classification by Sillence et al. [1] The 4 traditional groups of OI are type I, the mildest form, dominantly inherited with blue sclerae and usually presenting at school age; type II, a lethal perinatal form characterized by crumpled femora and beaded ribs; type III, which is progressively deforming and the most severe survivable form; and type IV, a dominantly inherited form with normal sclerae and moderate severity [3,4,5]. However, the classification of OI has been expanded to 8 types, incorporating cases with unidentified genetic defects and those with mutations in a gene affecting collagen type I hydroxylation [6,7]. Patients with OI often present with bone fragility, leading to frequent low-energy fractures that require surgical intervention. For patients with OI who undergo reverse total shoulder arthroplasty (RTSA), defective bone formation can present treatment challenges. The purpose of this case report is to describe difficulties and complications associated with the use of RTSA in a patient with OI. The patient was deceased at the time of submission of the case report, so informed consent was not obtained; the Johns Hopkins Institutional Review Board waived approval (IRB00463474).

A 67-year-old woman, who was a retired attorney, presented to our clinic with a history of osteoporosis (Z-score, –2.7), a diagnosis of OI, and a nonunion of a proximal humerus fracture. She had clinical features consistent with OI, including short stature (157 cm), blue sclerae, gray teeth, and a history of multiple low-energy fractures. She was seen by a genetic specialist, but despite negative testing for collagen type I alpha 1 chain (COL1A1) and collagen type I alpha 2 chain (COL1A2) genes, the conclusion was that she had an atypical variant of OI, and she was subsequently treated for years before presentation to an OI clinic. She was being treated with denosumab (Prolia; Amgen, Thousand Oaks, California, USA).

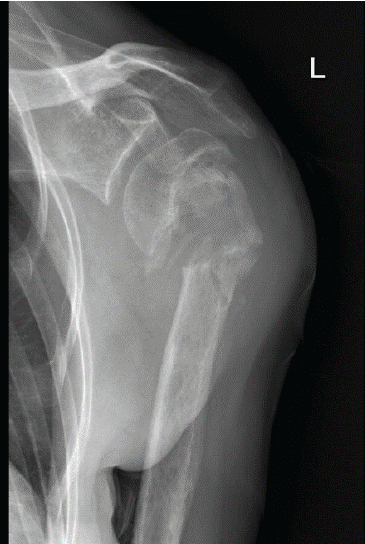

The patient reported left shoulder pain caused by nonunion of a proximal humerus fracture that was sustained in a fall 5 months earlier and managed with non-operative treatment (Fig. 1).

Figure 1: Pre-operative anteroposterior radiograph of the left shoulder of a 67-year-old woman with osteogenesis imperfecta showing atrophic nonunion of a proximal humerus fracture.

She had pain with any arm movement and at night. Physical examination revealed a very limited range of motion (ROM) in her left shoulder, including elevation of only 50°. She had weak abduction and external rotation, as well as a positive external rotation lag sign [8]. She was otherwise neurologically intact for sensation and motor nerve testing of the extremity. She had a history of infections, including fungal keratitis, septic bursitis, and infected gingival implants, as well as previous operations for fractures. After discussion of the alternative treatments for her proximal humerus fracture, she chose to undergo RTSA.

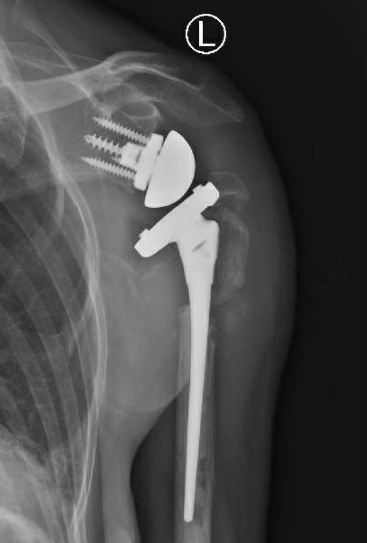

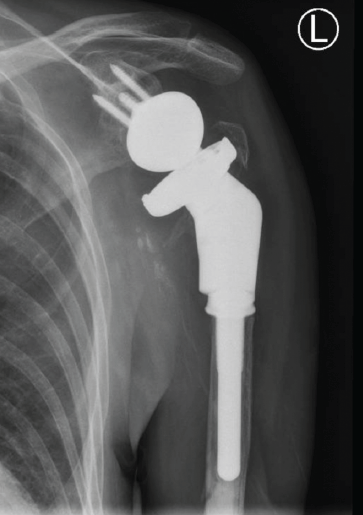

RTSA was performed under general anesthesia with an interscalene block for pain relief using the Comprehensive Reverse Shoulder System (Zimmer Biomet, Warsaw, Indiana, USA). The lesser and greater tuberosity fragments were mobilized, and no. 5 sutures (Ti-Cron, Medtronic, Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA) were placed at the bone-tendon interface to prevent comminution of the fragments. The glenoid baseplate and glenosphere were placed without difficulty despite soft glenoid bone. A distal cement restrictor was placed, and the implant was cemented into the humerus. Multiple variations of the glenoid tray and polyethylene components were used to create stability within the system construct. The tuberosities were secured to the humeral shaft using no. 5 sutures (Ti-Cron), which were placed before cementing (Fig. 2). No intraoperative complications were noted.

Figure 2: Anteroposterior radiograph taken after reverse total shoulder arthroplasty.

The patient was seen periodically after surgery with examinations and radiographs. At the 14-week post-operative appointment, she reported progressive shoulder pain without any trauma. The pain was exacerbated with any shoulder motion, and elevation was limited to 20°. Radiographs showed loosening of the humeral component (Fig. 3).

Figure 3: Anteroposterior radiograph showing infected primary reverse total shoulder arthroplasty. Note radiolucency around the implant.

The patient had no clinical signs of infection, such as redness, warmth, or drainage. Sedimentation rate and c-reactive protein were both normal. The joint was subsequently aspirated under sterile conditions, and cultures were positive for coagulase-negative Staphylococcus and Propionibacterium granulosum 4 days later.

The patient subsequently underwent surgery, at which time no purulence was noted, and intraoperative tissue was determined by our musculoskeletal pathologists as having more than 5 white blood cells per high-powered field. Consequently, the prothesis was removed along with any remaining cement. Because there was a concern for infection, we placed a cement spacer impregnated with tobramycin and vancomycin. Postoperatively, after consultation with our infectious disease team, it was decided to treat the patient with a 6-week course of intravenous vancomycin.

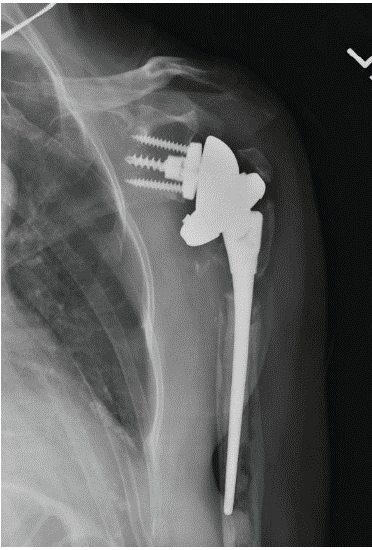

The second stage of the revision was performed 4 months after the antibiotic spacer was placed. Tissue at the time of the revision surgery revealed no white blood cells per high-powered field, so further reconstruction was performed with a custom tumor prosthesis (Comprehensive Segmental Revision System; Zimmer Biomet), which was cemented in the humeral shaft (Fig. 4).

Figure 4: Anteroposterior radiograph showing second stage of revision of reverse total shoulder arthroplasty with removal of the spacer and implantation of a tumor prosthesis.

Subsequently, she had no signs of infection. However, despite having less pain, she was disappointed with her restricted motion.

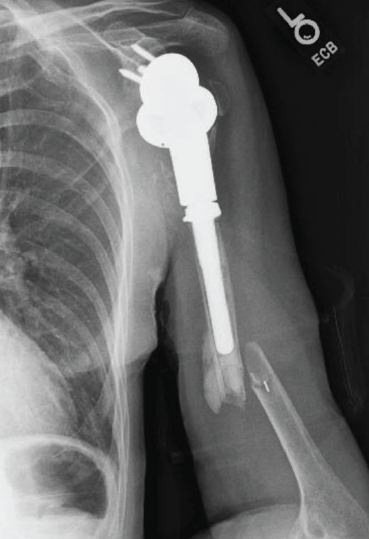

At 4 months after surgery, the patient fell in an elevator shaft in her home from a height of 1.2 m, landing on the operative arm. She sustained a fracture distal to the tip of the prosthesis (Fig. 5). She subsequently underwent open reduction and internal fixation with a plate and a fibular allograft for support.

Figure 5: Lateral radiograph of the humerus showing diaphyseal fracture distal to the tip of the prosthesis.

During the next 2 years, she had little pain but continued loss of ROM. At 26 months after the last operation, she developed a sense of instability, with the feeling that something was moving in the arm. Conventional radiographs showed that the custom tumor prosthesis had fallen into varus and was eroding through the humerus (Fig. 6).

Figure 6: Anteroposterior radiograph showing reduction of the fracture, secured in place with a fibular allograft strut and long plate. The humeral component gradually loosened and migrated into varus, as seen here.

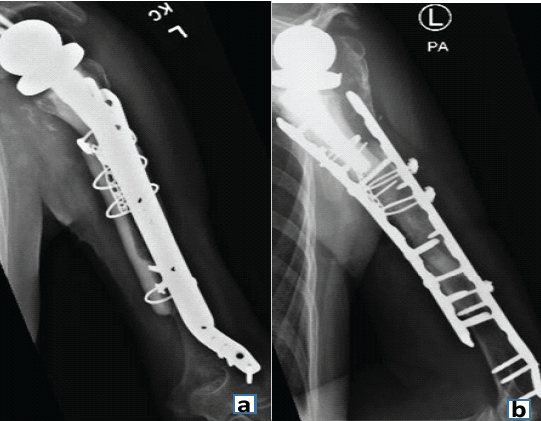

Laboratory tests and aspiration showed no signs of infection. Magnetic resonance imaging of the shoulder showed a moderate-grade partial tear in the supraspinatus tendon (3–4 mm) but no evidence of tendon retraction. Because her pain became intolerable, she underwent another revision, and histological testing did not find any signs of infection. At the time of surgery, the humeral component was found to be completely loose. The humeral stem was removed manually along with the cement distally, with no difficulty. Specimens obtained at the time of surgery did not demonstrate any signs of infection on histological analysis. An allograft-prosthetic composite (APC) was then used to reconstruct the proximal humerus. The APC was constructed with a cemented short-stem humeral component (Zimmer Biomet) in the proximal humeral allograft. The APC was fixed internally to the existing humerus and previously placed allograft using 2 plates (Fig. 7).

Figure 7: Anteroposterior (a) and lateral (b) radiographs showing finished reconstruction using allograft and plate.

Postoperatively, the APC remained stable. The patient had no pain at rest but still reported pain with most motions. Although she had limited elevation, she had a negative external rotation lag sign and could reach her mouth easily. Her last radiographs, taken 3 months later, showed no signs of loosening of the APC, suggesting that bone formation had bridged the gap between the native bone and the APC. She subsequently fell again in her home and sustained an intracranial hemorrhage, from which she died.

This case reflects the challenges associated with fixation of fractures in patients with OI, particularly fractures of the proximal humerus, where the bone is often soft. The complexities of treating patients with OI are compounded by persistent difficulty in achieving bone healing because of the unique pathophysiology in this population.

Prosthesis failure in RTSA is often multifactorial, as illustrated by this case, in which identifying a single primary cause was challenging. Revision RTSA is associated with higher rates of complication and reoperation compared with primary procedures [9,10]. Wall et al. [11] reported nearly 4 times the incidence of complications in patients who underwent revision RTSA compared with those who underwent primary RTSA. Common complications in primary RTSA include instability, humeral issues (loosening, rotation, or fracture), and infection [9,12,13,14]. Similarly, a study of 29 patients with OI reported that fracture complications included nonunion or delayed union (11%), malunion (6%), and implant loosening (6%) [15]. As many as 20% of patients with OI will experience nonunion of at least 1 fracture during their lives [15]. This case study highlights the complexity of implant failure in patients with OI who are treated for nonunion complications.

Evidence suggests that patients with OI have increased susceptibility to septic arthritis and osteomyelitis [16]. Infection was an important factor in implant failure after the first RTSA in our case [17,18,19]. However, after the 2-stage revision, infection was unlikely to be the main cause of the first implant failure. Although studies have shown that bone healing rates in patients with OI may not be substantially impaired, the fragility of newly formed bone presents a high risk of fracture [20,21,22,23,24,25]. Therefore, implant failure 3 years after the second-stage revision was likely caused by bone loss and brittleness.

The limited reports of outcomes of RTSA in patients with OI show promising results with cemented fixation. Mnif et al. [26] reported successful use of bilateral cemented total shoulder arthroplasty for a bilateral posterior fracture-dislocation in a patient with OI. Their patient had improved pain and ROM at 3-year follow-up. McLaughlin et al. [27] also described successful outcomes in a patient with OI who had a proximal humeral enchondroma and articulation between the acromion and humeral head. Cemented fixation in RTSA in this case was not effective, and supplemental fixation with plates should be considered in this patient population.

Humeral bone density also affects the support of the humeral implant. Mengers et al. [28] reported a 24% reoperation rate in patients without OI who had proximal humerus bone loss, with a high relative risk of humeral loosening in patients who had undergone multiple prior procedures of the operative arm. In patients with OI, lower-extremity conditions, such as fractures and osteoarthritis, are more common because of the weight-bearing demands on the lower extremities. Mengers et al. [28] and Roberts et al. [29] reviewed outcomes of lower-extremity arthroplasty in patients with OI, finding poor outcomes attributed to subchondral bone quality and recommending cemented components for fixation. When arthroplasty fails in a patient with OI, it often leads to complex revision surgeries necessitated by bone loss, deformity, or complications from previous operations [30]. However, we are aware of no similar studies of the treatment of proximal humerus fractures or arthroplasty in the glenohumeral joint for patients with OI. Although our case was complicated by an early infection, it was treated successfully with medication. Therefore, the subsequent fractures and poor healing were likely related to OI.

This case underscores the profound challenges associated with surgical treatment of fractures in patients with OI, particularly in the context of RTSA. Further research and case studies are needed to better understand and address the challenges of this patient population to ensure the best possible outcomes.

When performing shoulder arthroplasty to treat shoulder fractures in patients with OI, supplemental fixation with plates and allograft reinforcement should be considered.

References

- 1. Sillence DO, Senn A, Danks DM. Genetic heterogeneity in osteogenesis imperfecta. J Med Genet 1979;16:101-16. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 2. Van Dijk FS, Sillence DO. Osteogenesis imperfecta: Clinical diagnosis, nomenclature and severity assessment. Am J Med Genet A 2014;164A:1470-81. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 3. Sillence D. Osteogenesis imperfecta: An expanding panorama of variants. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1981;159:11-25. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 4. Subramanian S, Anastasopoulou C, Viswanathan VK. Osteogenesis imperfecta. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing; 2024. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 5. Zaripova AR, Khusainova RI. Modern classification and molecular-genetic aspects of osteogenesis imperfecta. Vavilovskii Zhurnal Genet Selektsii 2020;24:219-27. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 6. Cabral WA, Chang W, Barnes AM, Weis M, Scott MA, Leikin S, et al. Prolyl 3-hydroxylase 1 deficiency causes a recessive metabolic bone disorder resembling lethal/severe osteogenesis imperfecta. Nat Genet 2007;39:359-65. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 7. Rauch F, Glorieux FH. Osteogenesis imperfecta. Lancet 2004;363:1377-85. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 8. Hertel R, Ballmer FT, Lombert SM, Gerber C. Lag signs in the diagnosis of rotator cuff rupture. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 1996;5:307-13. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 9. Boileau P. Complications and revision of reverse total shoulder arthroplasty. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res 2016;102:S33-43. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 10. Rittmeister M, Kerschbaumer F. Grammont reverse total shoulder arthroplasty in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and nonreconstructible rotator cuff lesions. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2001;10:17-22. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 11. Wall BT, Mottier F, Walch G. Complications and revision of the reverse prosthesis: A multicenter study of 457 cases. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2007;16:e55. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 12. Boileau P, Melis B, Duperron D, Moineau G, Rumian AP, Han Y. Revision surgery of reverse shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2013;22:1359-70. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 13. Cheung E, Willis M, Walker M, Clark R, Frankle MA. Complications in reverse total shoulder arthroplasty. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2011;19:439-49. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 14. Zumstein MA, Pinedo M, Old J, Boileau P. Problems, complications, reoperations, and revisions in reverse total shoulder arthroplasty: A systematic review. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2011;20:146-57. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 15. Chiarello E, Donati D, Tedesco G, Cevolani L, Frisoni T, Cadossi M, et al. Conservative versus surgical treatment of osteogenesis imperfecta: A retrospective analysis of 29 patients. Clin Cases Miner Bone Metab 2012;9:191-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 16. Bobak L, Dorney I, Lavu MS, Mistovich RJ, Kaelber DC. Increased risk of osteomyelitis and septic arthritis in osteogenesis imperfecta. J Pediatr Orthop B 2024;33:290-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 17. Folkestad L, Hald JD, Canudas-Romo V, Gram J, Hermann AP, Langdahl B, et al. Mortality and causes of death in patients with osteogenesis imperfecta: A register-based nationwide cohort study. J Bone Miner Res 2016;31:2159-66. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 18. McFarland EG, Rojas J, Smalley J, Borade AU, Joseph J. Complications of antibiotic cement spacers used for shoulder infections. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2018;27:1996-2005. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 19. Storoni S, Treurniet S, Micha D, Celli M, Bugiani M, Van Den Aardweg JG, et al. Pathophysiology of respiratory failure in patients with osteogenesis imperfecta: A systematic review. Ann Med 2021;53:1676-87. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 20. Agarwal V, Joseph B. Non-union in osteogenesis imperfecta. J Pediatr Orthop B 2005;14:451-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 21. Brand J, Tyagi V, Rubin L. Total knee arthroplasty in osteogenesis imperfecta. Arthroplast Today 2019;5:176-80. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 22. Chalmers PN, Boileau P, Romeo AA, Tashjian RZ. Revision reverse shoulder arthroplasty. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2019;27:426-36. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 23. Familiari F, Rojas J, Nedim Doral M, Huri G, McFarland EG. Reverse total shoulder arthroplasty. EFORT Open Rev 2018;3:58-69. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 24. Gamble JG, Rinsky LA, Strudwick J, Bleck EE. Non-union of fractures in children who have osteogenesis imperfecta. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1988;70:439-43. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 25. Josse J, Valour F, Maali Y, Diot A, Batailler C, Ferry T, et al. Interaction between staphylococcal biofilm and bone: How does the presence of biofilm promote prosthesis loosening? Front Microbiol 2019;10:1602. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 26. Mnif H, Koubaa M, Zrig M, Zrour S, Amara K, Bergaoui N, et al. Bilateral posterior fracture dislocation of the shoulder. Chir Main 2010;29:132-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 27. McLaughlin RJ, Watts CD, Rock MG, Sperling JW. Reverse total shoulder arthroplasty in a patient with osteogenesis imperfecta type I complicated by a proximal humeral enchondroma: A case report and review of the literature. JSES Open Access 2017;1:119-23. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 28. Mengers SR, Knapik DM, Strony J, Nelson G, Faxon E, Renko N, et al. The use of tumor prostheses for primary or revision reverse total shoulder arthroplasty with proximal humeral bone loss. J Shoulder Elb Arthroplast 2022;6:24715492211063108. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 29. Roberts TT, Cepela DJ, Uhl RL, Lozman J. Orthopaedic considerations for the adult with osteogenesis imperfecta. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2016;24:298-308. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 30. Sanz-Ruiz P, Villanueva-Martinez M, Calvo-Haro JA, Carbó-Laso E, Vaquero-Martín J. Total femur arthroplasty for revision hip failure in osteogenesis imperfecta: Limits of biology. Arthroplast Today 2017;3:154-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]