Total Hip Replacement after acetabular fracture fixation is technically demanding but yields excellent outcomes when performed with proper planning, appropriate implant removal, and implant selection based on bone quality.

Dr. Ashutosh Kumar, Department of Orthopaedics, Emergency and Trauma Centre, Indira Gandhi Institute of Medical Sciences, Patna, Bihar, India. E-mail: dr.ashutoshkr@gmail.com

Introduction: Post-traumatic arthritis following acetabular fracture fixation is the most common cause of chronic hip pain and disability. Following an acetabular fracture, there is a high chance of secondary osteoarthritis; thus, the total hip replacement (THR) serves as a reliable procedure. However, doing THR after prior open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF) of the acetabulum is technically challenging due to scarring, distorted anatomy, implant in situ, and scanty bone stock [1, 2, 3]. The study aims to assess the surgical difficulties, complications, and functional results in patients undergoing THR after acetabular fracture fixation.

Materials and Methods: It is a retrospective study conducted between January 2018 and December 2023. Thirty-one patients who had prior acetabular fixation and subsequently underwent THR were included. The demographics data, fracture pattern, surgical approach, implant type, and complications were recorded. Functional outcomes were assessed by using the Harris Hip Score (HHS) pre-operatively and following subsequent follow-up. Radiological evaluations were done to assess the component alignment, bone graft incorporation, and to determine if any signs of loosening.

Results: The mean age was 52.3 years (range: 38–72), with 21 males and 10 females. The mean follow-up was 18 months. The mean pre-operative HHS improved from 48 to 85 (P < 0.001). However, the major intraoperative difficulties included the previous implant, that is, acetabular plates or screw removal (30%), poor bone stock (20%), and difficult component positioning (26.7%). However, there were minimal complications. One patient had transient sciatic neuropraxia. There were no deep-seated infections, dislocations, or early loosening of implants reported. Both the cemented (11 cases) and uncemented (20 cases) THR provided satisfactory fixation.

Conclusion: THR after the acetabular fracture fixation is technically complex but gives excellent results when performed with meticulous surgical planning and proper implant selection. The cemented THR is done in old patients having osteoporotic bone, while uncemented components are done in younger patients, which gives long-term stability.

Keywords: Acetabular fracture, open reduction and internal fixation, post-traumatic arthritis, total hip replacement, arthroplasty.

Acetabular fractures are relatively uncommon but have clinically significant consequences. In association with pelvic injuries, acetabular fractures account for approximately 2–8% of all pelvic fractures [1]. Most of these injuries are associated with high velocity trauma, such as road traffic accidents, falls from height, or direct impact to the hip region [2]. The acetabulum has a complex anatomy, as it has a deep cup-like structure that incorporates the femoral head. Thus, when it fractures, it makes clinical presentation, diagnosis difficult, and finally, its treatment gets challenging. The most important thing is to prevent post-traumatic arthritis and to maintain hip joint congruency, which can be achieved by proper restoration of the acetabular articular surface. Open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF) is a gold standard treatment for displaced acetabular fractures [3,4]. The aim of the ORIF is to achieve the proper anatomical reduction and stable fixation, so that the integrity of the native hip joint is maintained. However, even with expert hands, the outcomes of acetabular fracture fixations are not always perfect. The data show that between 20% and 40% of patients develop secondary osteoarthritis changes and also have avascular necrosis of the femoral head in patients who were treated by ORIF, even though they have perfect intra op reduction and joint congruity and acceptable radiographic reductions [5,6,7]. The underlying cause is primarily due to initial cartilage damage, intra-articular debris, or residual incongruity. Moreover, secondarily having infection, hardware failure, and loss of fixation can accelerate more degenerative changes [8]. Once post-traumatic arthritis or avascular necrosis occurs, then the treatment of choice is total hip replacement (THR). As the THR restores function and finally relieves the pain. THR in a previously operated acetabular fracture has many issues. However, performing primary THR does not have such issues.

Doing secondary THR, there are a lot of issues there is distorted acetabular anatomy, loss of bony landmarks, acetabular plate and screw, bone defects, soft-tissue scarring, and compromised vascularity [9,10,11]. In addition, there is a higher risk of infection, blood loss, and intraoperative fractures further complicate the procedure [12].

Recent advancements in implants, such as 3D printing, robotic-assisted navigation surgery, and newly developed reconstructive techniques have improved the surgical outcome of THR [13,14,15]. Modular acetabular components, augmented porous metal, and advanced cementing techniques improve surgical outcomes. However, the complication rates remain higher (10–20%) than in primary THR [16,17,18].

The present study was conducted to evaluate the functional and radiological outcomes of patients who underwent THR after previous acetabular fracture fixation. The aim was to analyze technical challenges, complication rates, and the post-operative functional improvement using the Harris Hip Score (HHS) scoring systems.

A retrospective cohort study was carried out between January 2018 and December 2023. A total of 31 patients who underwent THR after previous ORIF for acetabular fracture were included. Institutional ethical approval was obtained no. 705/IEC/2025 IGIMS dated September 19, 2025. All patients above 18 years who previously underwent acetabular fixation and later required total hip replacement were included. These patients have symptoms of post-traumatic arthritis and have had a minimum of 6 months of follow-up.

However, the patients having active local or systemic infection, Pathological fractures, patients with incomplete clinical or radiographic records, and patients who lost follow-up within 6 months of post-surgery were excluded from the study.

Each patient underwent a complete pre-operative evaluation, which included a detailed history, clinical examination, and radiographic evaluation. The HHS is used for both pre- and post-assessment, which includes Pain level, walking tolerance, and functional capacity. Radiological evaluation was done by anteroposterior pelvis and Judet oblique views to identify non-unions, implant position, and acetabular morphology. Computed tomography scans were done in complex cases to assess bone stock and hardware interference with acetabular component placement. In suspected cases of infection, screening for erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, and joint aspiration is done [19]. Patients with raised markers underwent further evaluation to exclude any chronic infection. Patients having comorbidities, such as diabetes, hypertension, and cardiac disease were optimized before surgery.

All surgeries were performed by specialist arthroplasty surgeons with high experience in complex revision procedures.

The posterior (Kocher-Langenbeck) approach was used in 27 patients, while the lateral (Hardinge) approach was used in 4. The posterior approach is easier to assess the retained implant and easier to reconstruct the posterior column.

Previously implanted acetabular plate or screw removed only if they obstructed acetabular reaming or acetabular cup placement. If not required implant is not removed as it unnecessarily increases blood loss and surgical time.

Uncemented components were used in 20 patients with good bone quality and adequate acetabular support.

Cemented components were used in 11 elderly osteoporotic patients, as the literature favors cemented fixation in poor bone stock [20,21]. Intraoperatively, acetabular bone loss can be assessed, whether it may be cavitary or segmental. Cavitary defects were filled with morselized autograft. While the segmental defects were managed by using trabecular metal augments or mesh reinforcement, as required [22]. Perioperative antibiotics were given, and tranexamic acid was routinely used to minimize bleeding. Suction drains were used as required. After the operation, early mobilization was initiated within 48 hours, with partial weight-bearing as tolerated done by crutches. Full weight-bearing was allowed at 6 weeks, based on bone stock and fixation stability.

HHS was assessed pre-operatively and at 6, 12, and 18 months post-operatively. Radiographic evaluation of cup inclination and anteversion was measured as per Lewinnek’s safe zone. X-ray used to assess for component migration, radiolucent lines, or loosening. Both intraoperative (fracture, nerve injury, bleeding) and post-operative (infection, dislocation, loosening) complications were recorded.

Statistical analysis was done by using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences v26.0. The paired t-test compared pre- and post-operative HHS, with P < 0.05 considered significant.

Out of the 31 patients, 21 were male and 10 female, with a mean age of 52.3 years (range: 38–72 years). The right hip was involved in 28 patients, while the left in 3 patients. The average interval between primary acetabular ORIF and conversion to THR was 10.8 months (range: 2–24 months). Mechanisms of injury included road traffic accidents (83.8%) and falls from height (16.2%).

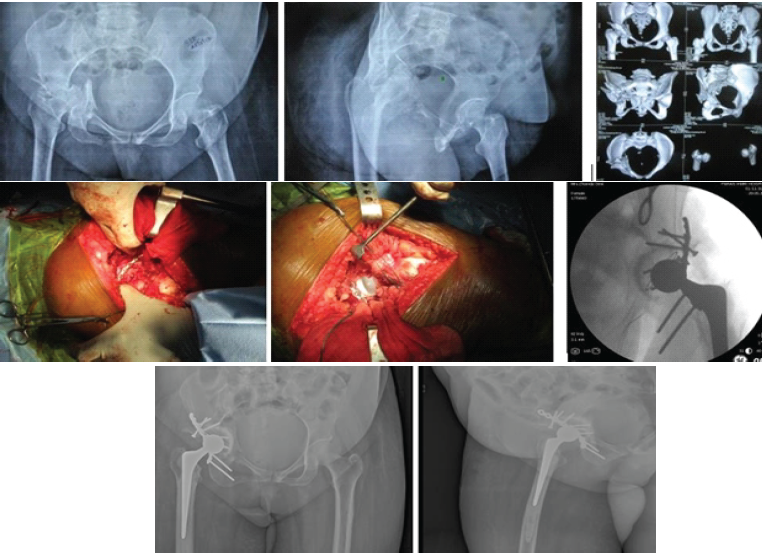

A patient with a central fracture-dislocation of the right hip is demonstrated. The fracture was addressed with posterior column fixation using the Kocher-Langenbeck approach, followed by cemented THR, as seen in the post-operative radiograph (Fig. 1).

Figure 1: (a) Pre-operative X-ray demonstrating a central fracture-dislocation of the right hip, (b) Posterior column fixation performed through the Kocher-Langenbeck approach followed by cemented total hip replacement. (c) Post-operative X-ray showing the final implant position.

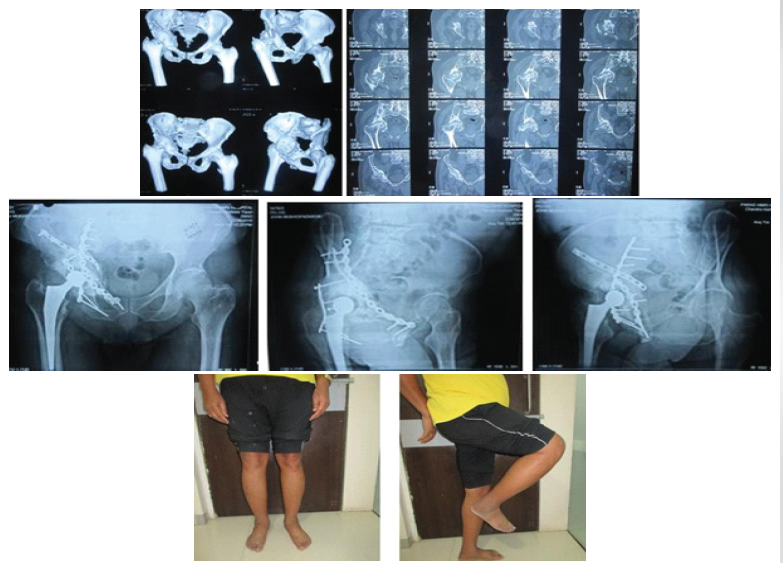

Similarly, (Fig. 2) illustrates a case of a both-column acetabular fracture. Dual plating of the anterior column through the ilio-inguinal approach, combined with posterior column fixation through the Kocher-Langenbeck approach, was followed by cemented THR. Post-operative clinical photographs show the patient achieving full weight-bearing with satisfactory active hip movements.

Figure 2: (a) Pre-operative imaging showing a both-column acetabular fracture, (b) Anterior column dual plating through the ilio-inguinal approach along with posterior column plating through the Kocher-Langenbeck approach followed by cemented total hip replacement, (c) Post-operative clinical photographs showing the patient standing with full weight-bearing and demonstrating active hip movements.

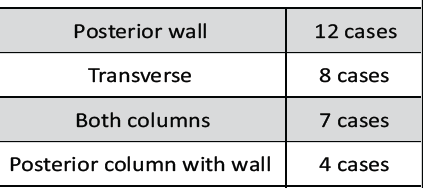

As per the Letournel classification, 12 cases were posterior wall fractures, 8 cases were transverse fractures, 7 cases had both columns, and 4 cases were posterior column fractures with posterior wall involvement (Table 1).

Table 1: Fracture classification as per the Letournel system

Mean pre-operative HHS was 48 ± 6, improving to 85 ± 5 at final follow-up (P < 0.001). Patients experienced better pain relief, improved gait, and increased walking ability. The majority of the patients had improved their ability to perform daily activities independently.

These findings are also noticed by Hung et al. (2023) [1] and Shaker et al. (2024) [2], who reported similar post-operative HHS improvements (82–88) in conversion THR patients.

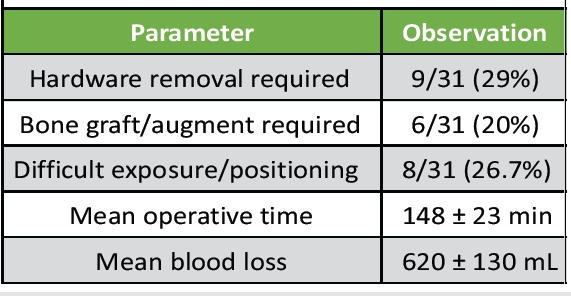

Intraoperatively, observation shows that hardware removal was required in 9 out of 31 cases (29%), and bone graft or augmentation was used in 6 cases (20%). Difficult exposure or positioning was encountered in 8 cases (26.7%). The mean operative time was 148 ± 23 min, and the average blood loss was 620 ± 130 mL (Table 2).

Table 2: Intraoperative observations

Post-operative complications were minimal. Transient sciatic neuropraxia was seen in 1 patient, which resolved in 3 months. No patients had deep-seated infection or dislocation. No patients had periprosthetic fracture or aseptic loosening of the implant in an 18-month follow-up case series. This shows that there is a lower complication rate as compared to previously published series [6,9,23].

Conversion THR following acetabular fracture fixation remains a technically demanding but it’s rewarding operation. The surgeon must be aware of altered anatomy, previous hardware, and deficient bone stock while having durable THR fixation and joint stability [24,25]. The present study shows that meticulous planning results in significant functional gains with minimal complications.

The major technical challenges were due to extensive soft tissue scarring, hardware interference while reaming, and cup placement. Bone loss may be seen due to the initial injury or hardware removal. There was an altered biomechanics of the acetabular dome [26]. The selective hardware removal avoided unnecessary dissection and minimized bleeding, similar to Kirkeboe et al. (2024) [7] and Kennedy et al. (2024) [4], who reported improved outcomes with limited hardware removal.

Prevention of bone loss remains the keystone in these surgeries. Cavitary defects respond well to impacted grafting, while segmental losses may require porous metal augments or reinforcement cages to fill the defect [27,28]. In our cohort study, 20% required bone grafting, similar to Giustra et al. (2024) [8]. Hip center restoration is a key point for long-term implant survival. The selection of an implant balance is based on patient age, bone quality, and expected activity level. Cemented fixation is used in osteoporotic patients [20]. While uncemented fixation offers superior biological integration and long-term durability in younger individuals [21,23]. In our study, the hybrid approach gives excellent radiographic stability in all cases, with no implant loosening seen. The reported complications range from 5 to 25% [17,25,28]; however, our study shows no infections or dislocations. The strict aseptic conditions, single-stage surgery, and limited dissection mainly contributed to this success. Li et al. (2023) [9] and Alqazzaz et al. (2023) [6] also highlight that infection risk can be minimized by thorough proper pre-operative screening and strict aseptic intraoperative sterility.

Meta-analyses show that mean post-operative HHS between 80 and 85, dislocation rates of 3–8%, infection rates of 2–6%, and loosening rates of 3–10% [12,15,17,18]. In our study, HHS 85, zero infection/dislocation, which compares favorably. We credit these to the surgeon’s expertise, modern implants, and strict patient selection.

Limitations

The study has some important limitations. The sample size of 31 patients is relatively small, which restricts both the statistical power and the generalizability of the findings. The mean follow-up period of 18 months may be insufficient to detect long-term complications, such as implant loosening or polyethylene wear. Because the research was conducted at a single center, the outcomes may not fully reflect results achievable in different surgical environments or by surgeons with varying levels of expertise. The absence of a control group further limits the ability to compare these results with those of primary THR or other revision procedures. In addition, variations in surgical techniques and implant choices introduce heterogeneity that may influence the interpretation of outcomes. In a few cases, incomplete radiological follow-up restricted the ability to perform detailed imaging assessments. Bone defects were not categorized using standardized systems, such as the Paprosky classification, which hinders comparison with other studies. Functional evaluation relied exclusively on the HHS, and including tools, such as WOMAC or HOOS might have provided a more comprehensive assessment. Finally, excluding patients who were lost to follow-up may have introduced selection bias. This is a retrospective study and a small sample size, which limits the generalizability of results. The relatively short follow-up (mean 18 months) may under-rate the late complications, such as loosening or polyethylene wear. The future multicenter prospective studies with longer follow-up are needed to clearly understand how long the implant lasts [29,30].

The THR following acetabular fracture fixation is a complex yet effective procedure for managing post-traumatic arthritis.

Despite surgical challenges, proper pre-operative planning, selective hardware removal, and appropriate implant selection give excellent functional outcomes.

In expert hands, conversion THR can give results comparable to primary THR, restoring mobility and good quality of life for these difficult cases.

Conversion to THR after acetabular fracture fixation gives pain-free mobility and good joint stability when performed with proper planning and modern reconstruction techniques. It is a technically demanding procedure that gives good outcomes, and it is a viable salvage procedure for post-traumatic arthritis.

References

- 1. Hung CC, Chen KH, Chang CW, Chen YC, Tai TW. Salvage total hip arthroplasty after failed internal fixation for proximal femur and acetabular fractures. J Orthop Surg Res. 2023;18:45. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 2. Shaker F, Esmaeili S, Taghva Nakhjiri M, Azarboo A, Shafiei SH. The outcome of conversion total hip arthroplasty following acetabular fractures: a systematic review and meta-analysis of comparative studies. J Orthop Surg Res. 2024;19:83. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 3. Abdelmoneim M, Farid H, El-Nahal AA, Mohamad MM. Evaluation of total hip arthroplasty for management of acetabular fracture complications: a prospective cohort study. J Musculoskelet Surg Res. 2024;8(3):210-220. doi:10.25259/JMSR_90_2024. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

- 4. Abdelmoneim M, Farid H, El-Nahal AA, Mohamad MM. Evaluation of total hip arthroplasty for management of acetabular fracture complications: A prospective cohort study. J Med Sci Res. 2024;8(3):210-220. doi:10.25259/JMSR_90_2024. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

- 5. Cimerman M, Kristan A, Jug M, Tomaževič M. Fractures of the acetabulum: from yesterday to tomorrow. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. 2021;45:1057-1064. Published 2020 Sep 22. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 6. Rashed M, Hildebrand F, Hofmann U, Horst K, Hürtgen B, Bolierakis E, Berk T. Acute total hip replacement of acetabular fractures with cementless modular revision cups in patients older than 55 years: a retrospective cohort study. 2025. doi:10.21203/rs.3.rs-7350551 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

- 7. Banskota B, Bhandari AR, Aryal R, Pandey NR. Total hip arthroplasty following acetabular fracture fixation: a functional outcome study. Nepal Orthop Assoc J. 2025;11(1). doi:10.59173/noaj.20251101b. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

- 8. Giustra F, Cacciola G, Pirato F, Bosco F, De Martino I, Sabatini L, Rovere G, Camarda L, Massè A. Indications, complications, and clinical outcomes of fixation and acute total hip arthroplasty for the treatment of acetabular fractures: a systematic review. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol. 2024;34:47–57. Published 2023 Aug 28. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 9. Li J, Jin L, Chen C, Zhai J. Predictors for post-traumatic hip osteoarthritis in patients with transverse acetabular fractures following open reduction internal fixation: a multicenter study with minimum 2-year follow-up. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2023;24(1). doi:10.1186/s12891-023-06945-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

- 10. Shaker F, Esmaeili S, Taghva Nakhjiri M, Azarboo A, Shafiei SH. The outcome of conversion total hip arthroplasty following acetabular fractures: a systematic review and meta-analysis of comparative studies. J Orthop Surg Res. 2024;19:83. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 11. Deirmengian GK, Zmistowski B, O’Neil JT, Hozack WJ. Management of acetabular bone loss in revision total hip arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93(19):1842–1852. doi:10.2106/JBJS.J.01197 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

- 12. Patil PH, Pamarathi S. Assessment of clinical and functional outcomes following uncemented total hip arthroplasty in failed primary hemiarthroplasty. Int J Res Orthop. 2017;3, doi:10.18203/issn.2455-4510.IntJResOrthop20171894 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

- 13. Shaker F, Esmaeili S, Taghva Nakhjiri M, Azarboo A, Shafiei SH. The outcome of conversion total hip arthroplasty following acetabular fractures: a systematic review and meta-analysis of comparative studies. J Orthop Surg Res. 2024;19:83. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 14. Makridis KG, Obakponovwe O, Bobak P, Giannoudis PV. Total hip arthroplasty after acetabular fracture: incidence of complications, reoperation rates and functional outcomes—evidence today. J Arthroplasty. 2014;29(7):1383–1389. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2014.06.001. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

- 15. Selim A, Dass D, Govilkar S, Brown AJ, Bonde S, Burston B, Thomas G. Outcomes of conversion total hip arthroplasty following previous hip fracture surgery. Bone Jt Open. 2024;6(2). doi:10.1302/2633-1462.62.BJO-2024-0188. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

- 16. Ljungdahl J, Hernefalk B, Pallin A, Brüggemann A, Hailer NP, Wolf O. Mortality and reoperations following treatment of acetabular fractures in patients ≥70 years: a retrospective cohort study of 247 patients. Acta Orthop. 2024. doi:10.2340/17453674.2024.42704. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

- 17. Kang SY, Ko YS, Kim HS, Yoo JJ. Outcome and complication rate of total hip arthroplasty in patients younger than twenty years: which bearing surface should be used? Int Orthop. 2024;48(6):1381–1390. doi:10.1007/s00264-023-06086-0 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

- 18. Makridis K, Obakponovwe O, Bobak PP, Giannoudis P. Total hip arthroplasty after acetabular fracture: incidence of complications, reoperation rates and functional outcomes—evidence today. J Arthroplasty. 2014;29(10). doi:10.1016/j.arth.2014.06.001 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

- 19. Rezaie AA, Blevins K, Kuo FC, Manrique J, Restrepo C, Parvizi J. Total hip arthroplasty after prior acetabular fracture: infection is a real concern. J Arthroplasty. 2020;35(9):2619–2623. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2020.04.085. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

- 20. Smith T, Nichols R, Donell ST, Hing C. The clinical and radiological outcomes of hip resurfacing versus total hip arthroplasty: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Acta Orthop. 2010;81(6):684–695. doi:10.3109/17453674.2010.533933. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

- 21. Yamada H, Yoshihara Y, Henmi O, Morita M, Shiromoto Y, Kawano T, Kanaji A, Ando K, Nakagawa M, Kosaki N, Fukaya E. Cementless total hip replacement: past, present, and future. J Orthop Sci. 2009;14(2):228–241. doi:10.1007/s00776-008-1317-4 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

- 22. Rosenthal B. Femoral defect classification in revision total hip arthroplasty. In: Parvizi J, Goyal N, Cashman J, editors. The Hip: Preservation, Replacement, and Revision. 1st ed. Data Trace Publishing Company; 2015. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 23. Tarabichi S, Parvizi J. Prevention of surgical site infection: a ten-step approach. Arthroplasty. 2023;5:21. Published 2023 Apr 8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 24. Shaker F, Esmaeili S, Taghva Nakhjiri M, Azarboo A, Shafiei SH. The outcome of conversion total hip arthroplasty following acetabular fractures: a systematic review and meta-analysis of comparative studies. J Orthop Surg Res. 2024;19:83. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 25. Kheir MM, Drayer NJ, Chen AF. An update on cementless femoral fixation in total hip arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2020; doi:10.2106/JBJS.19.01397. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

- 26. Kheir MM, Drayer NJ, Chen AF. An update on cementless femoral fixation in total hip arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2020; doi:10.2106/JBJS.19.01397. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

- 27. Slooff TJJH, Huiskes R, van Horn J, Lemmens AJ. Bone grafting in total hip replacement for acetabular protrusion. Acta Orthop Scand. 1984;55(6):593–596. doi:10.3109/17453678408992402. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

- 28. Zhou B, Chan PK, Wang D. The utilization of porous metal augments for acetabular reconstruction during revision total hip arthroplasty. Musculoskelet Surg. 2025; doi:10.1177/11207000251385230. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

- 29. Shang XF, Zhang XQ. Management of acetabular bone defect in revision hip arthroplasty. Zhonghua Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2024;62(9):818–822. doi:10.3760/cma.j.cn112139-20240617-00299. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

- 30. Sharath RK, Tribhuvan T, Chandran U, Shah RH, Kaushik A, Patil S, Hide (initials not provided). Mid-term results of total hip arthroplasty for post-traumatic osteoarthritis after acetabular fracture. Hip Pelvis. 2024;36(1):37–46. doi:10.5371/hp.2024.36.1.37. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]