Indigenous vacuum-assisted closure systems significantly reduce hospital stay, shorten healing time, lower the incidence of deep infections, enhance granulation tissue formation, and should be considered for early wound management, especially in developing countries.

Dr. Priti Ranjan Sinha, Department of Orthopaedics, Teerthanker Mahavir Medical College and Research Centre, Moradabad, Uttar Pradesh, India. E-mail: drpritiranjansinha@gmail.com

Introduction: Vacuum-assisted closure (VAC) has many advantages over standard wound therapy. However, its availability and associated high cost can be a disadvantage to the patients of developing countries, especially those coming from a poor background. There are some off-the-shelf indigenous-made VAC systems that can reduce the cost of VAC therapy by 20 times. However, there is a paucity of level one evidence on their efficacy. A randomized controlled trial was planned to evaluate the efficacy of indigenous VAC therapy as compared to standard wound therapy (SWT).

Materials and Methods: A double-blinded randomized controlled trial was conducted from December 2023 to April 2025. A total of 80 patients with Gustilo–Anderson type II/IIIA/IIIB open fractures were included in the study. After randomization, two groups (each containing 40 patients) were created. Group A received indigenous VAC therapy, and Group B received SWT. Outcomes such as duration of hospital stay, wound healing time, decrease in size of wound, formation of granulation tissue, infection rates, and other complications were assessed. The collected data were analyzed using SPSS v20.0.

Results: VAC Group had a statistically significant shorter duration of hospital stay (28.65 vs. 41.97 days, P = 0.002) and wound healing time (29.55 vs. 45.87 days, P = 0.017) as compared to the SWT group. Wound size reduction and granulation tissue formation were also found to be significantly better in the VAC group. Apart from this, infection rates were also lower in the VAC group (P = 0.045).

Conclusions: The use of indigenous VAC significantly reduces hospital stay, shortens healing time, lowers the incidence of deep infections and complications, and enhances granulation tissue formation when compared to SWT. Due to substantially reduced cost of treatment and better results, we strongly recommend the adoption of indigenous VAC systems for early wound management, especially in developing countries.

Keywords: Negative pressure wound therapy, indigenous vacuum therapy, open fracture, standard wound therapy, wound healing.

Wound healing, particularly in cases of open fractures, remains a significant challenge for orthopedic surgeons. Various wound dressing techniques have been described in the literature, among which vacuum-assisted closure (VAC) therapy is well-established, offering several documented advantages over conventional wound management methods [1-3]. However, the widespread use of VAC is hindered by factors such as limited availability and high cost, often exceeding $100 (approximately ₹8,500) per day [1,4]. This imposes a significant financial burden on patients in developing countries, especially those from economically disadvantaged backgrounds. With nearly 44% of the global population living below the poverty line [5], cost-reduction strategies in medical treatment are essential. In response, several indigenous, off-the-shelf VAC systems have been developed, reportedly reducing the daily cost of therapy to $4–8 (₹300–₹500) [1,4,6-8]. Despite their promising affordability, there is a paucity of level-one evidence regarding their effectiveness in wound management. To address this gap, a randomized controlled trial was designed to compare the efficacy of these indigenous VAC systems with standard wound therapy (SWT), conducted between December 2023 and April 2025.

This study was a randomized controlled study. The ethical clearance was obtained from the institutional ethical committee with approval number TMU/IEC/2024-25/005/025. A minimum sample size of 80 was calculated assuming a 95% confidence interval and an 80% power level, as well as the possibility of dropouts. All patients admitted to the Department of Orthopaedics, Teerthanker Mahaveer Medical College and Research Centre, Moradabad, Uttar Pradesh, India, between December 2023 and April 2025, who met the inclusion criteria, were enrolled in this study (n = 80).

Inclusion criteria:

All consenting patients aged 20–80 years presenting with open fractures classified as Gustilo–Anderson grade II, IIIA, or IIIB resulting from road traffic accidents were included in the study [9,10].

Exclusion criteria

Patients were excluded if they had open fractures older than 3 days, were previously operated on, had chronic osteomyelitis, were pregnant, required vascular surgical intervention, were malnourished, had pre-existing dermatological conditions, or were receiving immunosuppressive therapy. All patients were initially assessed and managed according to the Advanced Trauma Life Support guidelines in the emergency department [11]. Following adequate resuscitation and fracture classification, meticulous wound debridement was performed. Informed written consent was obtained from all participants in their native language. Participants were then randomized into two groups using simple random sampling through the lottery method. Group A (VAC group, n = 40) received an indigenous VAC therapy, whereas Group B (SWT group, n = 40) received SWT. All patients were started on a second-generation cephalosporin, unless culture and sensitivity reports indicated resistance, in which case antibiotics were modified accordingly.

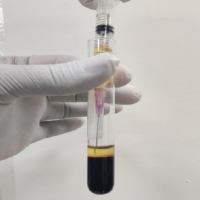

Indigenous vacuum-assisted closure technique

A commercially available open-cell polyurethane foam was sterilized using an autoclave in the hospital’s central sterile supply department. The foam was trimmed to match the wound dimensions, with an additional 5 mm overlap onto healthy skin. A fenestrated drainage tube was placed directly over the wound, followed by an additional foam layer of equal size. An iodine-impregnated adhesive drape (IOBAN) was applied over the foam and extended to cover at least 5 cm of the surrounding healthy skin to ensure an airtight seal (Fig. 1a,b,c,d,e. The drain tube was connected to a portable suction device, and a negative pressure of 125 mmHg was applied cyclically-30 min “on” followed by 3.5 h “off” (Fig. 2-5).

Figure 1: Steps of application of Indigenous VAC. (a) Sharp debridement (b) placement of foam and drain tube (c) airtight sealing with a piece of IOBAN drape (d) before negative pressure application (e) wrinkling and shrinkage after negative pressure application (VAC: Vacuum-assisted closure. IOBAN: Iodine impregnated).

Figure 2: Completely assembled indigenous vacuum-assisted closure machine. (a) Adhesive transparent dressing, (b) foam, (c) Ryle’s tube, (d) suction machine.

Figure 3: After meticulous wound debridement and external fixator application. Post-debridement wound over the lower leg – planned for the first vacuum-assisted closure application.

Figure 4: After the second vacuum-assisted closure (VAC) application. Post-second VAC application status of an open lower limb wound managed with external fixation, showing healthy granulation tissue.

Figure 5: After split-thickness skin grafting.

Post-operative image showing split-thickness skin graft secured with surgical staples over previously granulated wound bed, under external fixation stabilization.

The indigenous VAC dressing was changed every 3rd day. During each dressing change, parameters such as wound size, presence and amount of discharge, and granulation tissue formation were recorded. The VAC dressing was reapplied as needed based on clinical assessment.

In the SWT group, patients received daily dressing changes using normal saline and povidone-iodine, followed by sterile gauze and bandaging. Wound assessment data were collected every 3rd day, mirroring the VAC group protocol. In both groups, wound swab samples were collected weekly for culture and sensitivity testing.

Data were compiled using Microsoft Excel 2024 and analyzed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS), version 20.0. Blinding of study participants and the data analyst was maintained. However, blinding of the intervention provider was not feasible, as all cases were managed under the supervision of a single senior orthopedic surgeon.

Categorical variables were presented as frequencies and percentages, whereas continuous variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation. The unpaired t-test was used to compare continuous variables between groups, whereas the Chi-square test was employed for categorical data. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant (Table 1).

Table 1: Comparison of treatment protocol.

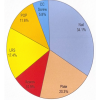

Among the total of 80 enrolled cases of open fractures, 60 (75%) were males and 20 (25%) were females (Table 2).

Table 2: Distribution of study subjects according to gender in both study groups.

The mean age was 34.475 ± 8.64 years for the VAC group and 41.275 ± 12.574 for the SWT group (Table 3).

Table 3: Distribution of study subjects according to age in both study groups.

However, there was no significant difference between the two intervention groups in terms of age.

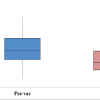

The mean number of stay in hospital in the indigenous VAC group (28.65 days) was significantly lower when compared to the SWT Group (41.97 days) (P <0.05) (Table 4).

Table 4: Mean duration of hospital stay (days) in both study groups.

The VAC group had a statistically significant higher mean decrease in size of wound in week 1 (2.14 cm vs. 1.23 cm; P = 0.049) and week 2 (2.77cm vs. 1.32 cm; P = 0.049). However, after the 3rd week, there was no statistically significant difference in the mean decrease in size of the wound (Table 5).

Table 5: Mean decrease in size of wound (cm) in both study groups with time.

There was a statistically significant increase in the formation of granulation tissue in the VAC group as compared to the SWT group, with P = 0.041 after week one and 0.032 after week 2. All cases (n = 40, 100%) in the VAC group showed the formation of granulation tissue after week 1, 2, and 3. Whereas only 72% cases (29 out of 40) had the granulation tissue after week 1 (Table 6).

Table 6: Formation of granulation tissue in both study groups with time.

Mean wound healing time was significantly more in Group B (SWT, 45.87 days), as compared to Group A (incisional vacuum-assisted closure [IVAC], 29.55 days) (P < 0.05). (Table 7) The mean duration of hospital stay was significantly more in Group B (SWT, 41.97 days) than in Group A (IVAC, 28.65 days) (P < 0.05) (Table 7).

Table 7: Mean wound healing time (days) in both study groups.

Group A (VAC) had just one case of swab stick growth after the 1st and 2nd weeks, as compared to Group B (SWT), which had 7 cases (17.5%) with growth after the 1st week, which was found to be statistically significant (Table 8).

Table 8: Growth of bacterial culture in both study groups with time.

There was no statistically significant difference in terms of comorbidities of study participants in both groups (P > 0.05) (Table 9).

Table 9: Distribution of study subjects according to comorbidities in both study groups.

There was a statistically significant difference in terms of complications of study participants in both groups in terms of infection rates and delayed wound healing (P < 0.05) (Table 10).

Table 10: Complications in both study groups with time.

VAC therapy is a well-established modality in the management of complex wounds and has become a standard of care in many clinical settings [1]. Initially introduced by Argenta and Morykwas in 1997, VAC has demonstrated substantial benefits in optimizing wound conditions for spontaneous healing [2]. The application of subatmospheric pressure enhances local blood flow, reduces edema, and limits bacterial colonization, factors that collectively promote granulation tissue formation and wound healing [12]. For acute traumatic wounds, a negative pressure of 125 mmHg below ambient pressure is generally recommended. Pressures significantly higher than this – such as 500 mmHg – can lead to excessive mechanical deformation of tissues, resulting in decreased perfusion and impaired granulation tissue formation [1,13]. Intermittent negative pressure has been shown to be superior to continuous suction in promoting vascular perfusion. The “off” cycle of intermittent suction allows tissue reperfusion, and studies have reported nearly double the rate of granulation tissue formation with intermittent therapy (103%) compared to continuous therapy (63%) [1,2]. An airtight seal is critical to the effectiveness of VAC therapy. The dressing must be applied such that the foam, tubing, and at least 3–5 cm of surrounding healthy tissue are completely covered with adhesive drapes to ensure a proper seal [14]. Breaches in the seal, resulting in air leaks, can disrupt the negative pressure environment and lead to suboptimal outcomes. In our clinical experience, educating patients about how to recognize air leaks or device malfunctions plays a crucial role in maintaining dressing integrity and improving treatment outcomes. The indigenous VAC system used in our study was assembled using low-cost, hospital-available components, which significantly reduced treatment costs, approximately 20-fold lower than commercial VAC systems. Cost reduction is especially vital in developing countries where a significant portion of the population lacks access to advanced wound care due to financial constraints.

While previous studies have explored the use of indigenous VAC systems with favorable outcomes, many relied on in-line wall suction, necessitating hospital admission and inadvertently increasing treatment costs [1]. In contrast, our system employed a portable suction machine, allowing for potential outpatient (domiciliary) management. Although all VAC dressings in our study were performed in an inpatient setting, the use of portable suction enables future applications in outpatient departments, further reducing the overall health-care burden. Our findings demonstrated that the indigenous VAC system significantly reduced hospital stay duration and resulted in a greater reduction in wound size compared to the SWT group. These results are consistent with those reported by Kumaar et al. and Singh et al. [4,15]. Furthermore, the VAC group exhibited shorter mean wound healing time and fewer culture-positive wound swabs, mirroring findings from previous studies by Kumaar et al., Singh et al., Choudhary et al., and De Caridi et al. [4,7,15,16].

Limitations

This randomized controlled trial had several limitations. The study focused solely on the early phase of wound healing and involved a relatively small sample size. In addition, potential confounding factors – such as smoking status, injury severity, and comorbid conditions beyond diabetes and hypertension – that could influence wound healing outcomes were not controlled for in this analysis.

The use of an indigenous VAC system significantly reduced hospital stay, accelerated wound healing, decreased the incidence of deep infections and complications, and enhanced granulation tissue formation compared to SWT. Developed using readily available local materials, this indigenous VAC system offers a highly cost-effective alternative for patients from low-income backgrounds, particularly in resource-limited health-care settings. The clinical outcomes observed in our study were comparable to those reported with commercially available VAC systems, while the cost of treatment was substantially lower. Given that conventional VAC systems remain financially inaccessible for many patients in developing countries, we strongly advocate for the broader adoption of indigenous VAC systems in early wound management. This approach has the potential to significantly reduce the overall economic burden of treatment without compromising therapeutic efficacy.

Indigenous vacuum-assisted closure (IVAC) represents an effective and economical modality for wound management, and it should be strongly considered in resource-limited setting.

References

- 1. Agarwal P, Kukrele R, Sharma D. Vacuum assisted closure (VAC)/negative pressure wound therapy (NPWT) for difficult wounds: A review. J Clin Orthop Trauma 2019;10:845-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 2. Argenta LC, Morykwas MJ. Vacuum-assisted closure: A new method for wound control and treatment: Clinical experience. Ann Plast Surg 1997;38:563-76; discussion 577. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 3. Webb LX. New techniques in wound management: Vacuum-assisted wound closure. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2002;10:303. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 4. Singh A, Panda K, Mishra J, Dash A. A comparative study between indigenous low cost negative pressure wound therapy with added local oxygen versus conventional negative pressure wound therapy. Malays Orthop J 2020;14:129-36. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 5. World Bank Group. Pathways Out of the Polycrisis: Main Messages. Poverty, Prosperity, and Planet Report; 2024. p. 1-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 6. Charles NR, Gupta A, Datey S, Lohia R. Negative pressure wound therapy by indigenous method: A decisive and cost-effective approach in management of open wounds. Int Surg J 2016;9:1399-406. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 7. Choudhary A, Joshi M, Lamoria N. Indigenously prepared intermittent negative pressure wound dressing: Effective and economic in Indian scenario. Indian J Phys Med Rehabil 2022;32:2-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 8. Gupta GK, Shukla GK, Rani S, Chakraborty R, Kumar T, Siddhant NC. Indigenous negative pressure wound therapy: A low-cost equivalent alternative to conventional vacuum-assisted closure therapy – a prospective randomized open-blind endpoint study. Ann Afr Med 2025; May 30. French, English. doi: 10.4103/aam.aam_215_24. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 40445362 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

- 9. .Gustilo RB, Anderson JT. Prevention of infection in the treatment of one thousand and twenty-five open fractures of long bones: Retrospective and prospective analyses. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1976;58:453-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 10. Kim PH, Leopold SS. Gustilo-anderson classification. Clin Orthop 2012;470:3270-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 11. American College of Surgeons. Advanced Trauma Life Support: Student Course Manual. 10th ed. Chicago, IL: American College of Surgeons; 2018. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 12. Genecov DG, Schneider AM, Morykwas MJ, Parker D, White WL, Argenta LC. A controlled subatmospheric pressure dressing increases the rate of skin graft donor site reepithelialization. Ann Plast Surg 1998;40:219-25. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 13. Timmers MS, Le Cessie S, Banwell P, Jukema GN. The effects of varying degrees of pressure delivered by negative-pressure wound therapy on skin perfusion. Ann Plast Surg 2005;55:665-71. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 14. Ellis G. How to apply vacuum-assisted closure therapy. Nurs Stand 2016;30:36-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 15. Kumaar A, Shanthappa AH, Ethiraj P. A comparative study on efficacy of negative pressure wound therapy versus standard wound therapy for patients with compound fractures in a tertiary care hospital. Cureus 2022;14:23727. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 16. De Caridi G, Massara M, Greco M, Pipitò N, Spinelli F, Grande R, et al. VAC therapy to promote wound healing after surgical revascularisation for critical lower limb ischaemia. Int Wound J 2016;13:336-42. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]