Dog bite avulsion amputation is not an absolute contraindication to thumb replantation in young children when early debridement, rabies prophylaxis confirmation, and expert microsurgical repair are employed.

Dr. Karn Maheshwari, Department of Hand and Microsurgery, Krisha Hospital, Ahmedabad, Gujarat, India. E-mail: karnpmaheshwari@gmail.com

Introduction: Dog bite injuries are common, but dog bite avulsion amputations are rare, and in the pediatric population, they are even rarer. We report a successful thumb replantation in a 2-year-old girl following avulsion amputation from a canine attack, representing one of the youngest cases to date, and review relevant literature to emphasize the importance of multidisciplinary management.

Case Report: A 2-year-old girl presented with a complete thumb avulsion at the proximal phalanx after a dog bite, having also sustained a prior bite 1 week earlier. The amputated digit underwent 5–6 h of cold ischemia and about 1 h of warm ischemia before microsurgical replantation. Multidisciplinary consensus involving plastic, orthopedic, and infectious disease consults supported replantation. The procedure included thorough debridement, skeletal fixation, vascular and nerve repair, with empiric broad-spectrum antibiotics. A localized infection at 20 days resolved with targeted intervention. At 18 months follow-up, the child achieved full functional recovery: Zero visual analog scale pain, restored grip strength, near-normal range of motion, and excellent standardized scores (Tamai, QuickDASH). Age-appropriate psychosocial adjustment was confirmed by the young child PTSD checklist and pediatric quality of life inventory.

Conclusion: This case demonstrates that replantation can be feasible and successful in select pediatric dog bite-related amputations despite contamination, when supported by aggressive debridement and infectious disease–optimized care. The outcome highlights the regenerative capacity in children and reinforces the role of multidisciplinary management in expanding replantation indications for contaminated traumatic injuries.

Keywords: Thumb replantation, dog bite injury, avulsion amputation, microsurgery, pediatric trauma, contaminated wound.

Dog bites represent a major global public health concern, accounting for 60–90% of all mammalian bites and causing approximately 4.5 million injuries annually in the United States, with nearly 337,000 requiring emergency intervention [1,2]. In India, the estimated incidence is 6.6 per 1,000 population, translating to about 9.1 million dog bite cases annually and contributing significantly to rabies mortality [3]. These injuries most frequently affect the hands due to instinctive defensive movements, particularly among children and middle-aged adults [4]. Dog bite injuries to the hand especially the thumb pose serious risks of infection because of deep, polymicrobial contamination, reported in nearly one-third of cases [2]. The mechanism typically involves crushing, tearing, or avulsion from canine masticatory forces, producing complex soft-tissue, vascular, nerve, and osseous trauma [1,5]. Microbiological profiles are polymicrobial, commonly containing Pasteurella canis, Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus species, and anaerobes such as Fusobacterium and Bacteroides [6]. In immunocompromised patients, Capnocytophaga canimorsus may cause fulminant systemic infection, emphasizing the importance of early irrigation, debridement, and antibiotic administration – ideally within 6 h – to reduce infection rates from 59% to 8% [2]. Microsurgical replantation techniques have advanced substantially, with success rates now ranging from 50% to 85% [7,8]. Functional recovery, not mere survival of the replanted part, defines modern success, and thumb replantation can restore up to 84% of grip strength with good sensory outcomes, particularly in children [8,9]. Although traditionally contraindicated in contaminated crush or avulsion injuries, recent literature supports replantation in selected dog bite amputations when aggressive debridement, vascular repair, and targeted infectious disease management are applied. Such cases remain exceptionally uncommon, underscoring the clinical value of the present report that describes successful pediatric thumb replantation following a dog bite-induced avulsion injury [7,10].

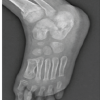

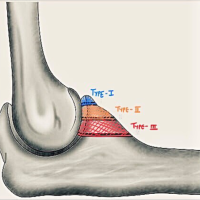

A 2-year-old girl presented to our tertiary care hospital with a complete avulsion amputation of the right thumb at the level of the proximal phalanx following a street dog bite. The incident occurred in the morning. The parents acted swiftly, demonstrating exceptional presence of mind by retrieving the amputated segment from the dog’s mouth within a minute. They immediately transported the child to a primary health center, where the digit was preserved in a moist cloth, sealed in a plastic bag, and placed on ice in accordance with preservation guidelines. Notably, the child had sustained a separate dog bite one week prior, and rabies post-exposure prophylaxis had already been initiated. Her immunization history was current, including tetanus, with no known allergies, previous surgeries, or chronic conditions; growth and development were appropriate for her age. The patient arrived at our facility approximately three hours post-injury, alert and hemodynamically stable. Local examination revealed a Gustilo–Anderson Type IIIC injury with a transverse fracture at the base of the proximal phalanx and complete avulsion, classified as Tamai Zone III (Fig. 1).

Figure 1: At arrival.

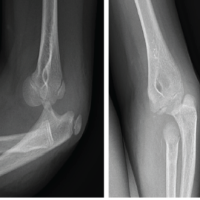

The wound edges displayed irregular tearing consistent with a bite mechanism. However, the amputated unit was well-preserved, with clearly identifiable tendons, arteries, and nerves. X-rays confirmed the amputation level and absence of foreign bodies or major contamination, validating the efficacy of initial management (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: Pre-operative X-ray.

Given the child’s stability and the thumb’s critical role in hand function, replantation was indicated. The injury was complicated by the avulsion mechanism, which caused extensive vessel damage and severely narrowed the digital arteries. Unlike clean-cut injuries, this necessitated aggressive debridement and rendered microvascular repair technically demanding, with vessel diameters measuring as small as 0.3 mm. A critical perioperative challenge involved the dual risk of wound contamination and potential rabies transmission, as the amputated thumb remained in the dog’s mouth for nearly 1–2 min. Given the near-100% fatality of clinical rabies, surgery would have been futile without established immunity. Following consultation, the infectious disease team confirmed adequate antibody protection from the prior exposure, permitting the surgical team to proceed.

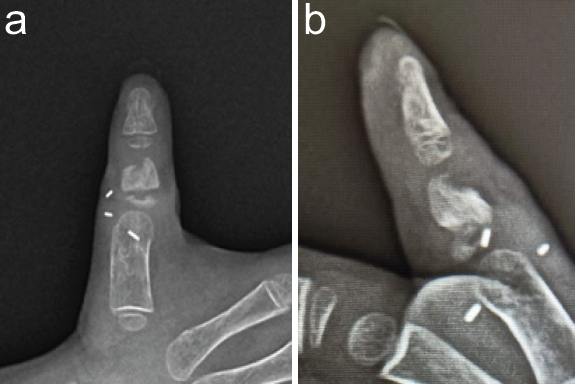

Following family consent, the six-hour procedure was performed under general anesthesia in the early afternoon. The total cold ischemia time was 5–6 h, with approximately 1 hour of warm ischemia. The patient was positioned supine with the right hand mid-prone, utilizing a pneumatic tourniquet at 180 mmHg for 90 min during the microsurgical phase. Thorough debridement of both the stump and amputated part revealed minimal tissue loss (Fig. 1). Skeletal stabilization involved shortening the bone by approximately 2 mm to facilitate tension-free soft tissue repair while preserving the growth plate. A single 1.5 mm Kirschner wire was inserted longitudinally to provide stable fixation (Fig. 3).

Figure 3: Post-operative.

Post-operative radiographs verified satisfactory bone alignment and K-wire positioning (Fig. 4a and 4b).

Figure 4: (a) Post-operative X-ray anteroposterior view. (b) Post-operative X-ray lateral view.

Tendon repair was executed using 6–0 to 4–0 Prolene sutures. The radial digital artery, measuring roughly 0.3 mm, underwent end-to-end anastomosis with 10–0 Ethilon sutures under high magnification. Similarly, the radial digital nerve was coapted with 9–0 Ethilon using fine epineural sutures, and one dorsal digital vein was repaired for venous drainage. Skin closure utilized 4–0 Ethilon in a tension-free manner, intentionally leaving small gaps to aid drainage and perfusion monitoring. Upon tourniquet release, the thumb regained pink color and warmth with a capillary refill under 30 s, confirming successful revascularization. The hand was subsequently dressed and immobilized (Fig. 5).

Figure 5: Dressing.

Postoperatively, the patient was monitored in a high-dependency unit with continuous assessment of color, temperature, turgor, and capillary refill. Perfusion remained stable throughout the early recovery phase. Broad-spectrum antibiotics were administered per dog bite protocols under infectious disease guidance. While initial healing was uncomplicated within a plaster cast, a mild local infection manifested during the 3rd post-operative week, characterized by a small area of pus at the suture line without fever or systemic symptoms (Fig. 6).

Figure 6: Infection after 3 weeks of surgery.

This was managed with dressing changes and an adjusted antibiotic course following pediatric review. The infection resolved within 2 weeks, and the replanted thumb remained healthy (Fig. 7).

Figure 7: After infection subsides (initial 1 month infected resolved).

The patient received antibiotic therapy including amoxicillin-potassium clavulanate injection and syrup formulations of Augmentin and Tormoxin clav, administered intravenously and orally as per infectious disease specialist guidance, adhering to standard dog bite wound management protocols [13]. At approximately 3 months, the Kirschner wire was removed, and gentle range-of-motion exercises commenced. The parents demonstrated full involvement and compliance with the home rehabilitation plan, leading to progressive improvement in thumb mobility and function.

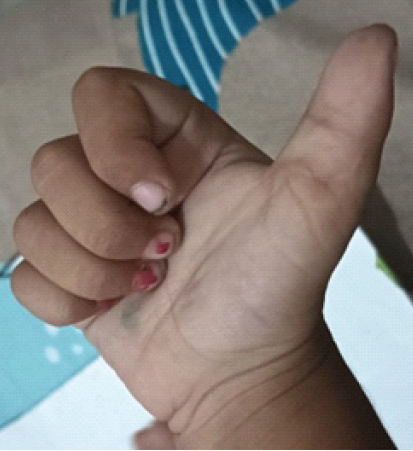

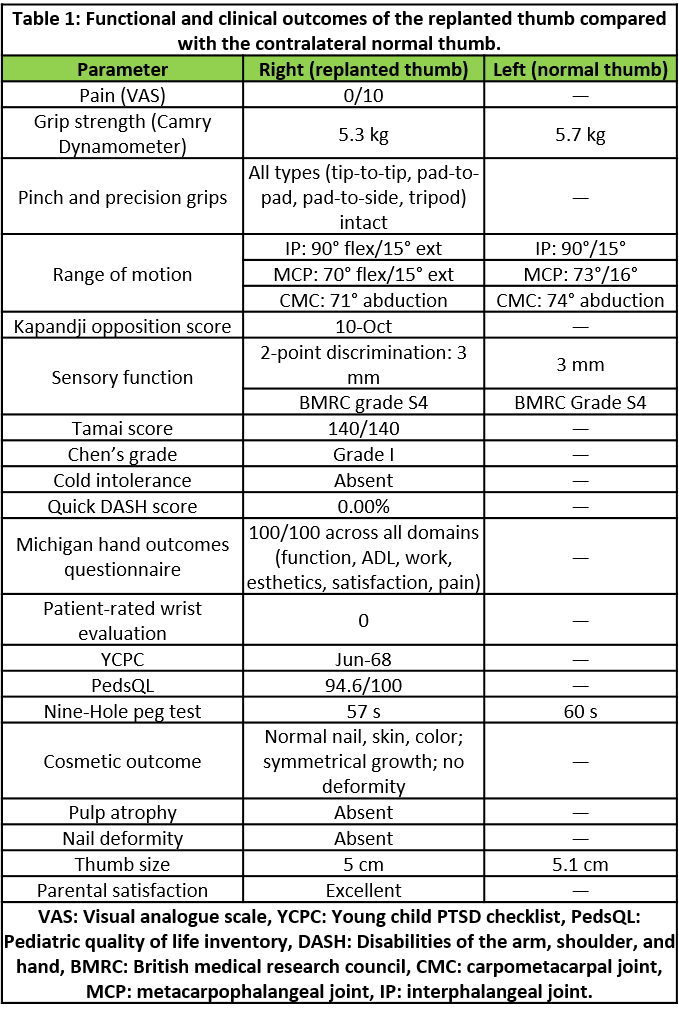

Functional outcome measures were selected based on validated instruments for digital replantation reported by Cho et al. [8], including grip strength, range of motion, two-point discrimination, Tamai scoring system, Chen’s functional grading, QuickDASH, Michigan Hand Outcomes Questionnaire, and Patient-Rated Wrist Evaluation. Additionally we took Paediatric Quality of Life Inventory (PedsQL) for health-related quality of life across physical, emotional, social, and school functioning domains, and Young Child PTSD Checklist (YCPC) for trauma-related psychological symptoms including fear of dogs, other animals, and behavioural changes. Although assessments in this age group rely on parent reports and this is a known limitation, they remain the accepted standard in paediatric orthopaedics. At 18 month follow-up, the replanted thumb resulted excellent functional recovery across all outcome measures (Figure 8, Table 1).

Figure 8: Post 18 months.

Table 1: Functional and clinical outcomes of the replanted thumb compared with the contralateral normal thumb.

Grip strength measured 5.3 kg on the replanted side compared to 5.7 kg on the contralateral normal side, representing 93% recovery and exceeding the typical 84% reported in adult replantation series [8]. Active range of motion showed interphalangeal joint flexion of 90° (normal: 90°), metacarpophalangeal joint flexion of 70° (normal: 73°), and carpometacarpal abduction of 71° (normal: 74°), corresponding to 95% of contralateral motion. Opposition function was excellent with Kapandji score of 10/10, indicating the thumb could reach all reference points including the base of the fifth finger. Precision grip patterns including tip-to-tip, pad to-pad, pad-to-side, and tripod pinch were all intact and functional for age-appropriate tasks. Two-point discrimination measured 3 mm, classified as British Medical Research Council (BMRC) Grade S4, representing superior recovery compared to typical adult outcomes of 5 to 7 mm [9]. Static and moving two-point discrimination were equal, suggesting mature sensory reinnervation. Protective sensation was fully restored with normal response to light touch, pin-prick, and temperature. Cold intolerance, commonly reported after digital replantation, was completely absent. Objective functional assessment demonstrated optimal standardised scores: Tamai score 140/140 (excellent grade), Chen’s functional grading Grade I (excellent), QuickDASH score 0% (indicating no disability), Michigan Hand Outcomes Questionnaire 100/100 across all domains (function, activities of daily living, work, aesthetics, satisfaction, pain), and Patient-Rated Wrist Evaluation score 0 suggestive of no impairment. The replanted thumb maintained normal nail growth, skin colour, and contour without deformity. Thumb length measured 5.0 cm compared to 5.1 cm contralaterally, showing symmetric growth without discrepancy. A well-healed 2.4 cm dorsal scar was present but did not restrict motion, and no pulp atrophy, trophic skin changes, or nail dystrophy were observed. The Young Child PTSD Checklist (YCPC) scored 6/68, well below the clinical threshold, indicating absence of post-traumatic stress symptoms including fear of dogs, anxiety around animals, or behavioural regression. The Paediatric Quality of Life Inventory (PedsQL) scored 94.6/100, approaching normal population values for healthy children. Both parents and treating clinicians independently confirmed the child’s return to all age-appropriate activities, including effective thumb use for fine motor tasks such as grasping small objects, holding utensils, and early writing skills. Also she had successfully commenced preschool education with full participation in all activities without functional limitations.

Dog bite injuries represent a significant paediatric public health concern, particularly for children under five years of age who bear the highest burden due to their proximity to dog faces and inability to recognize danger. A nationwide analysis of 56,106 paediatric dog bite presentations demonstrated clear age-related anatomic patterns: facial injuries predominate in toddlers (82.5%), transitioning to upper extremity involvement in adolescents (40.9%), with only 8.0% requiring operative repair [11]. Beyond their high incidence, these injuries present complex reconstructive challenges arising from polymicrobial contamination, tissue crush or avulsion patterns, and the psychological impact of trauma at a critical developmental stage. Complete digit-level amputations from dog bites remain exceptionally rare in young children [12], making successful thumb replantation in our 2-year-old patient particularly noteworthy. The exceptional functional recovery observed in our patient—specifically 93% grip strength, 95% range of motion, Tamai score 140/140, and QuickDASH 0%—challenges traditional contraindications and expands the indications for paediatric microsurgery when multidisciplinary protocols are rigorously applied.

A systematic review (PubMed, Scopus, Google Scholar; 2000–2024) revealed a striking lack of paediatric digit-level replantation cases following dog bites. To the best of our knowledge, this represents the first reported case of successful thumb replantation in a child under five years of age following a dog bite-induced avulsion amputation. We conducted a focused literature review via PubMed, Scopus, and Google Scholar from 2000 to 2024 using the keywords “paediatric,” “thumb replantation,” “dog bite,” and “avulsion amputation.” Previous reports of thumb replantation following dog trauma are restricted to adults, such as the 94-year-old patient described by Budini et al. [7], or to limb-level replantation in older children, exemplified by the forearm replantation in a 16-year-old girl reported by De Vitis et al. [5]. No peer-reviewed cases were identified involving digital-level replantation, specifically isolated thumb salvage, in toddlers or preschool-aged children. This absence confirms the rarity of the present case. The technical success and satisfactory functional outcomes achieved here suggest that thumb replantation—even with avulsion injury and polymicrobial contamination from a dog bite—is feasible in carefully selected paediatric patients when microsurgical capabilities and appropriate antimicrobial protocols are available.

Our patient’s outcomes substantially exceed reported paediatric benchmarks, with 3 mm two-point discrimination and a Kapandji score of 10/10 at 18 months reflecting superior paediatric regenerative capacity compared to the 40–60% permanent deficit expected with revision amputation [8]. Dog bite wounds contain polymicrobial flora, including Pasteurella canis, Staphylococcus aureus, and anaerobes [4,6]. Historically, dog bites were positioned as absolute contraindications to replantation based on the presence of these organisms combined with avulsion-induced tissue damage. However, aggressive debridement within six hours reduces infection rates from 59% to 8%, and when combined with targeted antimicrobial therapy, it creates an opportunity for successful revascularization [2]. Therefore, contamination alone should not preclude reconstructive efforts when infection control and microsurgical competency intersect appropriately.

Considerable controversy remains regarding the indications for replantation in contaminated paediatric amputations. While revision amputation is often tempting due to shorter operative times, single-stage recovery, and predictable wound healing, it results in lifelong deficits affecting fine motor development and hand dominance [8]. Our case presented an additional challenge—namely, dual contamination and rabies exposure, as the amputated segment remained in the dog’s mouth for 1-2 minutes. Infectious disease serological confirmation of adequate antibody protection from prior prophylaxis transformed an apparent contraindication into a manageable risk. This emphasizes how consultation across multidisciplinary lines, rather than dogma, now defines the boundaries of paediatric replantation, while also highlighting an important knowledge gap: the lack of standardized protocols for rabies assessment in digit-level replantation.

This case provides actionable clinical principles. The mother’s immediate retrieval of the amputated thumb and arrival within three hours created the necessary temporal window for replantation, emphasizing the importance of public education regarding proper amputation preservation in moist gauze on ice. Contaminated paediatric amputations should not be reflexively deemed unsuitable; favourable factors include ischemia time less than six hours, identifiable vessels, confirmed rabies immunity, parental preference, and available microsurgical expertise . While any surgeon can initiate essential first steps—irrigation within six hours, proper preservation techniques, and infectious disease consultation [2,3]. definitive replantation requires specialized resources and urgent transfer to tertiary centres. Effective outcomes are contingent upon coordinated multidisciplinary care provided by surgeons, paediatricians, infectious disease experts, and rehabilitation therapists.

This report bears the inherent limitations of a single case like limited generalizability, selection bias, and an 18-month follow-up period, which may not reliably predict growth plate evolution or psychosocial adaptation in the long term. Furthermore, comparison to existing literature is complicated by the lack of standardized paediatric hand metrics. Future research should focus on developing multi-centre registries, standardized outcome tools, comparative studies stratified by contamination severity, and algorithmic triage based on ischemia time, contamination status, rabies status, and institutional resources. Cost-effectiveness modelling must also consider the lifelong occupational and functional consequences of revision amputation [8]. Routine reporting of paediatric amputations would convert anecdotal experience into actionable evidence to drive clinical decisions for this vulnerable population.

Dog bite thumb avulsion is not an absolute contraindication to replantation. This case demonstrates that prompt parental intervention, rabies immunity, and skilled microsurgery can turn a contaminated pediatric amputation into complete functional recovery. Mechanism of injury should not dictate management decisions; early debridement and control of infection should steer the course. Multidisciplinary management and public education are imperative. In certain pediatric cases, replantation should be attempted and will help formulate future protocols.

Contamination is not an absolute contraindication: Dog bite-related digit amputations can be successfully replanted when treated with early debridement (within 6 h), broad-spectrum antibiotics, and infectious disease-optimized protocols.

Limitations

As a single case report, this study lacks comparative data, standardized outcome measures, and key variables including dog breed and patient-dog familiarity. The retrospective, single institution design and small sample size limit generalizability and preclude definitive conclusions. The successful outcome reflects specific circumstances early presentation and multidisciplinary expertise. That may not be universally replicable across different healthcare settings or patient populations. Future research should establish standardized outcome measures, prospective multicentre registries, and larger comparative studies with long-term follow-up to develop evidence-based guidelines for contaminated paediatric digital replantation.

References

- 1. Giovannini E, Roccaro M, Peli A, Bianchini S, Bini C, Pelotti S, et al. Medico-legal implications of dog bite injuries: A systematic review. Forensic Sci Int 2023;352:111849. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 2. Maniscalco K, Marietta M, Edens MA. Animal bites. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing; 2025. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK430852 [Last accessed on 18 Nov 2025] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 3. Thangaraj JW, Krishna NS, Devika S, Egambaram S, Dhanapal SR, Khan SA, et al. Estimates of the burden of human rabies deaths and animal bites in India, 2022-23: A community-based cross-sectional survey and probability decision-tree modelling study. Lancet Infect Dis 2025;25:126-34. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 4. Nygaard M, Dahlin LB. Dog bite injuries to the hand. J Plast Surg Hand Surg 2011;45:96-101. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 5. De Vitis R, Cannella A, Cruciani A, Caruso L, Bocchino G, Taccardo G. Replantation dilemma: Lessons learned from managing a dog bite forearm amputation in a sixteen-year-old girl. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 2024;28:4149-55. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 6. Abrahamian FM, Goldstein EJ. Microbiology of animal bite wound infections. Clin Microbiol Rev 2011;24:231-46. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 7. Budini V, Costa AL, Sofo G, Bassetto F, Vindigni V. A challenging case of thumb replantation aided by intraoperative indocyanine green fluorescence angiography. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open 2024;12:e5670. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 8. Cho HE, Kotsis SV, Chung KC. Outcomes following replantation/revascularization in the hand. Hand Clin 2019;35:207-19. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 9. Taras JS, Nunley JA, Urbaniak JR, Goldner RD, Fitch RD. Replantation in children. Microsurgery 1991;12:216-20. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 10. Chang MK, Lim JX, Sebastin SJ. Current trends in digital replantation-a narrative review. Ann Transl Med 2024;12:66. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 11. Plana NM, Kalmar CL, Cheung L, Swanson JW, Taylor JA. Pediatric dog bite injuries: A 5-year nationwide study and implications of the COVID-19 pandemic. J Craniofac Surg 2022;33:1436-40. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 12. Duteille F, Hadjukowicz J, Pasquier P, Dautel G. Tragic case of a dog bite in a young child: The dog stands trial. Ann Plast Surg 2002;48:184-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 13. Jakeman M, Oxley JA, Owczarczak-Garstecka SC, Westgarth C. Pet dog bites in children: Management and prevention. BMJ Paediatr Open 2020;4:e000726. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]