Timely recognition and appropriate management of distal femoral physeal injuries in children ensure optimal recovery and minimize growth-related complications.

Dr. Sachin Kumar, Department of Joint Replacement and Orthopedics, TATA Main Hospital, Jamshedpur, Jharkhand, India. E-mail: drsachin@tatasteel.com

Introduction: The distal femoral physis makes an important contribution to limb length and is an uncommon bone to fracture in children. Complications associated with the fracture, such as vessel injury in the short term and angular deformities and limb length discrepancies in the long term, can be detrimental.

Case Report: A 7-year-old child presented with a distal femoral physeal injury, Salter–Harris type 2, without any associated neurovascular injury, following a road traffic accident. He was operated on the same day with closed reduction and fixation with multiple K wires. Recovery was uneventful, with a full range of movements. At 1-year follow-up, he was diagnosed with valgus deformity but no deterioration in function. This case underscores the importance of early diagnosis and treatment for distal femoral physeal injuries to prevent complications.

Conclusion: Distal femoral physeal fractures, though relatively uncommon, are associated with a higher incidence of complications. Timely diagnosis and treatment minimize the risk of complications. Even then, regular follow-ups are needed for early diagnosis of angular deformities and leg length discrepancies.

Keywords: Distal femoral physis, Salter–Harris fracture, K-wire fixation, pediatric orthopedics, valgus deformity

The distal femoral growth plate contributes to nearly 40% of the lower limb’s length. Consequently, any disruption, whether partial or complete, can lead to substantial angular deformities (such as genu valgum, genu varum, and recurvatum) or differences in limb length [1]. While uncommon, the proximity to the popliteal vessels means there is a potential risk for vascular complications if the growth plate is affected. Injuries to the distal femoral physis are typically caused by high-velocity trauma, often resulting in fractures that involve the growth plate [2]. Distal femoral physeal fractures are very rare. In one study on Japanese children, the incidence of this fracture was 3.2% of all physeal injuries [3]. Similarly, another study in the United States of America found the incidence to be 4% [4].

A 7-year-old male child presented to the Tata Memorial Hospital Emergency Department on March 14th, 2024, with complaints of pain and deformity in the right thigh following a road traffic accident. A speeding 2-wheeler hit him while he was returning from school. There was no history of loss of consciousness, ear, nose, or throat bleed, or vomiting. There was no history of any regular medication. On examination, the patient was conscious, oriented to time, place, and person, with normal temperature. Glasgow Coma Score was 15/15. The abdomen was soft, with normal bowel sounds. No evidence of any chest injury with bilaterally equal and comparable breath sounds. There was swelling and deformity in the right lower thigh just proximal to the knee joint (Fig. 1).

Figure 1: Pre-operative attitude of the limb.

The right lower limb was shortened and externally rotated. Tenderness and crepitus were noted over the right distal thigh. Both the active and passive range of motion at the right knee were severely restricted and painful. Distal pulses were well palpable, and sensations in the right lower limb were equal and comparable to those of the left lower limb. Active toe and ankle movements were present.

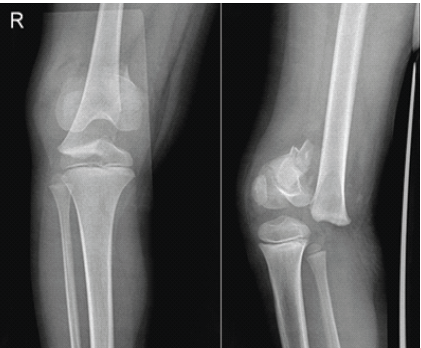

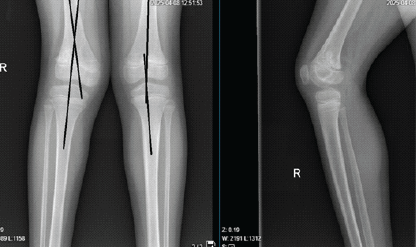

X-ray was advised, and findings were suggestive of a Salter–Harris type II fracture at the right distal femur (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: Pre-operative X-ray – anteroposterior and lateral views.

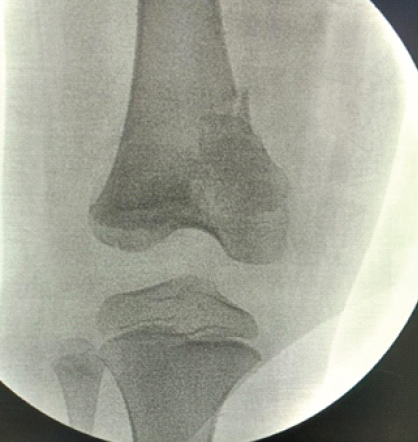

It was planned to attempt a closed reduction and stabilize the fracture with smooth Kirschner wires. The patient was posted for surgery in the emergency operating theatre on the same day. Under general anesthesia, the fracture was reduced with traction, countertraction, and gentle manipulation under C arm guidance (Fig 3).

Figure 3: Intraoperative C-arm image showing good reduction.

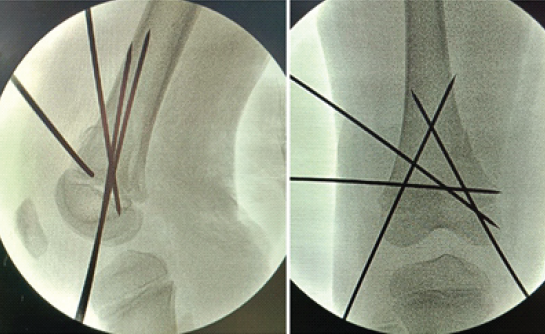

It was then stabilized with smooth K wires, as shown in intraoperative C-arm images, and an above-knee plaster of Paris slab was applied (Fig. 4).

Figure 4: Intraoperative C-arm image showing adequate reduction.

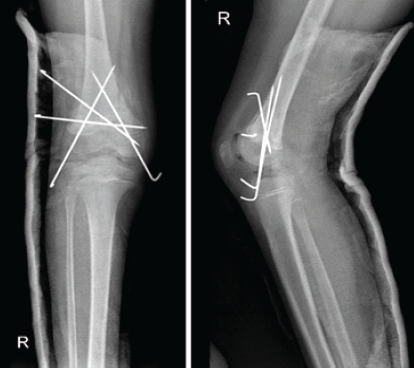

Post-operative recovery was uneventful, with the patient being discharged on day 2 of surgery after dressing and a check X-ray (Fig. 5).

Figure 5: Post-operative check X-ray – anteroposterior and lateral view.

He was followed up in the outpatient department at 2 weeks, 6 weeks, 2 months, 3 months, 6 months, and 1 year postoperatively. At the end of 2 months, the K-wires and slab were removed with gentle knee bending exercises. At 3 months, a repeat X-ray was obtained, which showed satisfactory union (Fig. 6).

Figure 6: X-ray right knee anteroposterior and lateral view at the end of 3 months.

Gradual weight bearing was allowed with physiotherapy for gait training. Patient was independently ambulating at the end of 3 and a half months. At the end of the 6-month follow-up, he is comfortably bearing weight (Fig. 7), squatting (Fig. 8) with a good range of motion (Fig. 9), and no apparent angular deformity or limb length discrepancy clinically. At the end of the 1-year follow-up, though the range of movements was normal, there was an evident valgus deformity clinically (Fig10), and at the distal femur 8° of valgus was measured on the radiograph (Fig 11) .

Figure 7: Child standing comfortably.

Figure 8: Child squatting comfortably.

Figure 9: Full flexion in the prone position.

Figure 10: Valgus deformity of the right leg is evident at 1-year follow-up.

Figure 11: Radiograph showing genu valgus deformity at the right knee.

Knee injuries are common among children, but fractures involving the distal femoral and proximal tibial growth plates are relatively uncommon [5]. These physeal fractures typically occur in children aged 9–14 [6]. As children grow, the epiphysis becomes less cartilaginous, and the secondary ossification center enlarges, making the epiphysis more rigid and less capable of absorbing energy. Consequently, forces are more likely to affect the physis, leading to a shift in the distribution of fractures, with most physeal knee fractures occurring after the age of 10 [7,8]. The most frequent type of injury is fractures of the distal femoral growth plate, followed by fractures of the proximal tibial growth plate. Since the majority of longitudinal growth occurs around the knee, particularly at the distal femur and proximal tibia, careful reduction and fixation are essential to avoid further damage to the growth plate, even with proper treatment, a significant risk of leg length discrepancies and angular deformities remains, necessitating close follow-up for at least 2 years [9]. In our case, we followed the child closely with clinical examinations and repeated radiographs, and at 1 year of follow-up, a valgus deformity of about 8° was noted. We have a further plan to monitor the child 6-monthly for another year and carry on further investigations to confirm a physeal bar formation, and go for its resection. The Salter–Harris classification system is used to categorize fractures in children based on the involvement of the physis, metaphysis, and epiphysis, which is important for determining both prognosis and treatment [10,11]. In this case, the fracture was classified as Salter–Harris Type II with a Thurston–Holland fragment, although the size of the fragment has little impact on the outcome [12]. Another key determinant of deformity following distal femoral physeal injury is the magnitude of displacement [13]. In our case, the displacement was significant, with a displacement in both radiographic views of >50% of the transverse diameter of the distal femoral metaphysis. For acute fractures, initial treatment involves a closed reduction and fixation under appropriate anesthesia. Salter–Harris Types I and II fractures that present 7–10 days after injury should allow for more leniency in accepting fracture displacement to avoid further injury to the physis [14]. In our case, the patient presented on the same day of injury and was taken up for closed reduction and fixation.

Fixation options for these fractures include cast immobilization for minimally displaced ones and smooth K-wire and screw fixation for displaced ones. At the same time, cases where the interposed periosteum blocks reduction may require open reduction and internal fixation. If open reduction is required, the fracture should be approached from the tension side to easily access the interposed tissue [15]. In this particular case, we have used multiple K-wires of 2 mm diameter for fixation of the fracture, with the ends of the K-wire kept outside the skin for easy removal. Following reduction and fixation, the fracture was initially stabilized additionally with cast immobilization for 8 weeks. The prognosis for physeal injuries depends on several factors, including the initial fracture type, location, degree of displacement, timeliness of treatment, quality of reduction, and subsequent orthopedic follow-up. In general, the outlook for pediatric physeal fractures is favorable, with most cases healing well with proper closed treatment. However, inappropriate initial management can increase the risk of growth arrest, malalignment, and long-term difficulties for the patient [16]. In our case, though, factors like initial displacement and mechanism of injury were not favorable with adequate and timely fixation; till date follow-up has shown promising results, with only the complication of valgus deformity seen at 1-year follow-up.

This case demonstrates that early diagnosis and treatment are the keys to managing pediatric physeal injuries. All pediatric physeal injuries should be reduced as early as possible, preferably under anesthesia. The choice of fixation for the fracture lies with the surgeon, taking into account the Salter–Harris classification, body habitus, and mechanism of injury; cast, K-wires, or screws may be used. In the short-term follow-up, any loss of reduction, infections, including septic arthritis of the knee, and knee stiffness should be looked for. Moreover, in the long term, one should be vigilant about the growth disturbances as consequences of physeal injury, particularly angular deformities and limb length discrepancies. Moreover, in our case, though being a high-energy trauma and a significant degree of displacement, the results were favorable, and only a valgus deformity was present at 1-year follow-up. We have a follow-up of about 1 year at the time of the submission of this case report, and more follow-up of about 1 year is needed to conclude any further increase of the valgus deformity and plan to address it.

Distal femoral physeal injuries are rare injuries in children; one has to be vigilant for the timely diagnosis and intervention. Follow-up is crucial for early diagnosis and treatment of angular deformities and limb length discrepancies.

References

- 1. Ambulgekar RK, Chhabda GK. A rare case of distal femur physeal fracture dislocation with positional vascular compromise in an adolescent male. J Orthop Case Rep 2022;12:101-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 2. Othman Y, Hassini L, Fekih A, Aloui I, Abid A. Uncommon floating knee in a teenager: A case report of ipsilateral physeal fractures in distal femur and proximal tibia. J Orthop Case Rep 2017;7:80-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 3. Kawamoto K, Kim WC, Tsuchida Y, Tsuji Y, Fujioka M, Horii M, et al. Incidence of physeal injuries in Japanese children. J Pediatr Orthop B 2006;15:126-30. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 4. Mann DC, Rajmaira S. Distribution of physeal and nonphyseal fractures in 2,650 long-bone fractures in children aged 0-16 years. J Pediatr Orthop 1990;10:713-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 5. Young EY, Stans AA. Distal femoral physeal fractures. J Knee Surg 2018;31:486-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 6. Young EY, Shlykov MA, Hosseinzadeh P, Abzug JM, Baldwin KD, Milbrandt TA. Fractures around the knee in children. Instr Course Lect 2019;68:463-72. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 7. Moran M, Macnicol MF. (ii) Paediatric epiphyseal fractures around the knee. Curr Orthop 2006;20:256-65. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 8. Persiani P, Ranaldi FM, Formica A, Mariani M, Mazza O, Crostelli M, et al. Apophyseal and epiphyseal knee injuries in the adolescent athlete. Clin Ter 2016;167:e155-61. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 9. Tandoğan NR, Karaeminoğullari O, Ozyürek A, Ersözlü S. Cocukluk ve ergenlik dönemindeki sporcularda diz çevresi kiriklari [Periarticular fractures of the knee in child and adolescent athletes]. Acta Orthop Traumatol Turc 2004;38 Suppl 1:93-100. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 10. Mills L, Zeppieri G Jr. Salter-Harris type III fracture in a football player. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2019;49:209. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 11. Binkley A, Mehlman CT, Freeh E. Salter-Harris II ankle fractures in children: Does fracture pattern matter? J Orthop Trauma 2019;33:e190-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 12. Turgut A, Kumbaraci M, Arli H, Çiçek AO, Sariekiz E, Kalenderer Ö. Does the size of Thurston-Holland fragment have an effect on premature physeal closure occurrence in type 2 distal tibia epiphyseal fractures? J Pediatr Orthop B 2022;31:e154-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 13. Arkader A, Warner WC Jr., Horn BD, Shaw RN, Wells L. Predicting the outcome of physeal fractures of the distal femur. J Pediatr Orthop 2007;27:703-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 14. Abzug JM, Little K, Kozin SH. Physeal arrest of the distal radius. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2014;22:381-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 15. Wuerz TH, Gurd DP. Pediatric physeal ankle fracture. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2013;21:234-44. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 16. Sabharwal S, Sabharwal S. Growth plate injuries of the lower extremity: Case examples and lessons learned. Indian J Orthop 2018;52:462-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]