In rare instances, pelvic osteochondromas may present along the inner or outer table of the ilium; surgical excision in these cases needs to be planned with the precise tumor location and its proximity to adjacent vital structures in mind.

Dr. Rupin Shreyas Singapanga, Department of Orthopaedics, Sri Ramachandra Institute of Higher Education and Research, Porur, Chennai - 600116, Tamil Nadu, India. E-mail: rups1996@gmail.com

Introduction: Osteochondromas are common benign bone tumors that usually present in the second or third decade of life with a slight male predilection. They may be isolated or multiple and frequently arise from the metaphyses of long bones. Rarely, they arise from atypical sites such as the scapula or pelvis. They are frequently asymptomatic and can be managed conservatively through serial monitoring and expectant observation, although en bloc excision, preferably following attainment of skeletal maturity, is advisable for symptomatic patients. Osteochondromas of the ilium are extremely rare, with few reports in the literature. Their management can be challenging, depending on their location and proximity to adjacent viscera and neurovascular bundles.

Case Report: We report the management of two patients with isolated pedunculated iliac osteochondromas. The first was a 13-year-old skeletally immature (Risser grade 0) boy who presented with a swelling over the right hemipelvis and limitation of hip movements. Radiographic and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) evaluation was suggestive of an osteochondroma over the inner table of the middle third of the ilium, in close proximity with the ascending colon. The second patient was a 19-year-old skeletally mature (Risser grade 5) boy who presented with complaints of a swelling over the right hemipelvis with pain on terminal hip range of movement. Radiographic and MRI evaluation was suggestive of an osteochondroma over the outer table of the anterior third of the ilium, slightly posterior to the anterior superior iliac spine. Both patients underwent en bloc surgical resection of the tumor. The first patient required additional repair of the anterior abdominal wall musculature, which required dissection for exposure of the tumor. Histopathologic examination confirmed that the lesions were osteochondromas. Both patients were asymptomatic with no evidence of tumor recurrence at their most recent follow-up.

Conclusion: Surgical excision of osteochondromas of the pelvis may be required for symptomatic patients, as well as asymptomatic patients when the tumor lies in close proximity with vital structures and is progressively growing in size. Meticulous surgical planning can prevent perioperative complications and result in satisfactory outcomes, even in skeletally immature patients.

Keywords: Osteochondroma, pelvic tumor, benign tumor, osteochondroma of ilium, bone tumor, en bloc excision.

Osteochondromas are common benign bone tumors. They represent nearly 15% of bone tumors overall, and about 45.3% of benign bone tumors [1]. They typically present in the second or third decade of life, with a slight male predilection [2]. They are solitary in nearly 85% of the cases, but may manifest as a part of hereditary multiple exostoses in up to 15% of the patients. They are frequently found arising from the metaphyseal regions of long bones such as the distal femur or the distal tibia. Rarely, they may originate from flat bones such as the scapula or pelvis. The incidence of pelvic osteochondromas is estimated to be around 5% of all osteochondromas. Among these, isolated osteochondromas of the outer or inner tables of the ilium are extremely rare, with few cases reported in the literature [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8]. We report the surgical management of two patients with isolated osteochondromas of the ilium. The first was a 13-year-old boy with an osteochondroma of the inner table of the ilium at the level of the middle third of the iliac wing; the second was a 19-year-old boy with an osteochondroma of the outer table of the anterior third of the ilium, just posterior to the anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS).

Case 1

A 13-year-old boy with no known comorbidities was brought by his parents to the orthopedic outpatient unit with complaints of a swelling around the right hemipelvis, which was noticed 3 months before his initial presentation following a history of a trivial trauma and was gradually progressive in size since then. He developed progressive limitation of hip flexion and difficulty squatting as the swelling increased in size. There was no history of swellings elsewhere over his body, fever, loss of appetite or weight, difficulty walking, or numbness or tingling along the right lower limb. On examination, a swelling was noted around the middle third of the right iliac crest, extending medially. The skin over the swelling appeared mildly stretched, with no erythema, scars, sinuses, or dilated veins. No tenderness or local rise of temperature was noted over the swelling. It was hard in consistency, immobile, and attached to the underlying bone. The skin over the swelling was pinchable. The inferomedial extent of the swelling was not discernible on clinical examination. Examination of the right hip and spine was unremarkable. No limb length discrepancy or distal neurovascular deficits were noted.

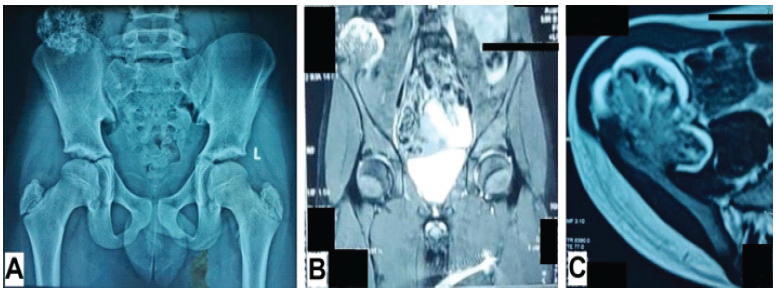

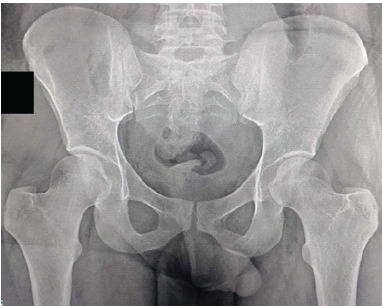

A preliminary pelvic radiograph revealed skeletal immaturity (Risser grade 0). The presence of a radio-opaque, popcorn-like mass arising from the inner table of the anterosuperior aspect of the right ilium was noted (Fig. 1). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) findings were pathognomonic for an osteochondroma, showing a well-defined pedunculated lesion arising from and continuous with the underlying ilium (Fig. 1).

Figure 1: Pre-operative radiologic investigations of the first patient. (a) Anteroposterior radiograph of the pelvis with both hips, (b) magnetic resonance imaging of pelvis (coronal section), and (c) magnetic resonance imaging of the right hemipelvis (transverse section). (Potential patient identifiers have been blacked out).

The thickness of the stalk of the lesion was noted to be approximately 2 cm. The mass was polypoidal in shape and measured 3.0 × 5.0 × 4.1 cm. An overlying cartilaginous cap measuring a maximum of 7 mm in thickness was noted. The lesion was found to be abutting the anterolateral abdominal wall and was in close proximity with the lateral aspect of the right psoas major muscle and the ascending colon. Superiorly, it extended up to the level of the inferior endplate of the L4 vertebra. No surrounding edema was noted, nor were signs of compression of the surrounding viscera or neurovascular structures. No pelvic lymphadenopathy was noted.

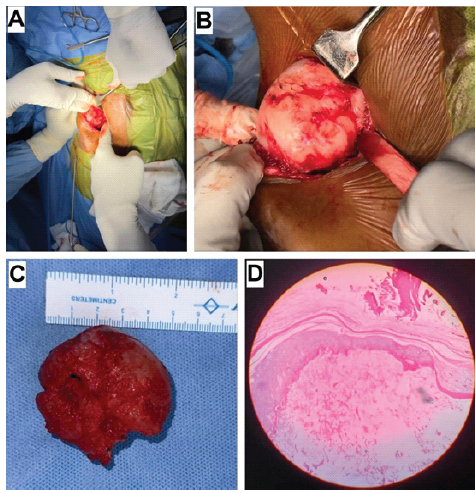

In view of the progressing size of the swelling, its close proximity to the ascending colon, and progressive functional limitation, surgery was advised. A general surgeon was available on standby at the time of surgery, given the location of the tumor in the inner table of the ilium and its close proximity to the ascending colon. Following spinal anesthesia, in the supine position, a linear incision was made over the iliac crest directly over the palpable mass. The fascia was dissected. The external and internal oblique muscles and the transversus abdominis were finger dissected distally along the direction of their respective fibers to uncover the tumor until the cartilaginous cap was exposed (Fig. 2). The surrounding musculature was retracted gently, and the pedicle of the tumor was exposed. En bloc resection of the tumor mass through the base of the pedicle along with a periosteal margin of 0.5 cm was performed using a curved osteotome (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: Images pertaining to the first patient. (a) Intraoperative image showing exposure of the tumor, (b) intraoperative image showing excision of the tumor using an osteotome, (c) gross appearance of the excised tumor, and (d) histopathologic appearance (Hematoxylin and Eosin) of the tumor at ×4 magnification, showing hyaline cartilage over osseous tissue.

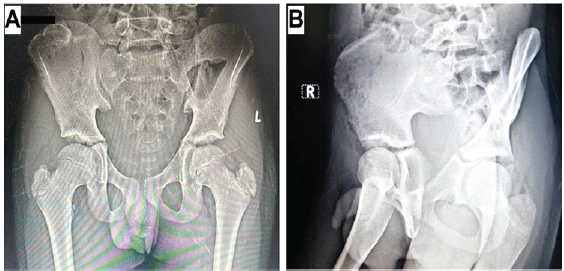

Dissection along the iliac crest was not performed to prevent physeal damage. Hemostasis was achieved by covering the bleeding bone end with bone wax. Adequacy of resection was confirmed under fluoroscopy. The abdominal wall musculature, and subsequently the surgical wound, was closed in layers. Histopathologic examination confirmed the pre-operative diagnosis of osteochondroma and showed the presence of hyaline cartilage with a fibrous perichondrial covering over osseous tissue (Fig. 2). The post-operative period was uneventful. There was no tumor recurrence at 6 months postoperatively (Fig. 3).

Figure 3: Post-operative radiographs of the first patient at the most recent follow-up. (a) Anteroposterior view of the pelvis and (b) iliac oblique view of the pelvis (Potential patient identifiers have been blacked out).

Case 2

A 19-year-old boy with no known comorbidities presented to our orthopedic outpatient unit with complaints of a swelling around the right hemipelvis since 1 year. The swelling gradually progressed in size during the first 4 months after it was first noticed but had stopped growing since then. There was no history of trauma, swellings elsewhere over his body, fever, loss of appetite or weight, difficulty walking, or numbness or tingling along the right lower limb. On examination, the swelling was found to be located along the anterior aspect of the right ilium around the region of the ASIS. The skin over the swelling appeared stretched, with no erythema, scars, sinuses, or dilated veins. No tenderness or local rise of temperature was noted over the swelling. It was hard, immobile, and attached to the underlying bone; the skin over the swelling was pinchable. Terminal hip movements were painful and restricted. Examination of the spine was unremarkable. No limb length discrepancy or distal neurovascular deficits were noted.

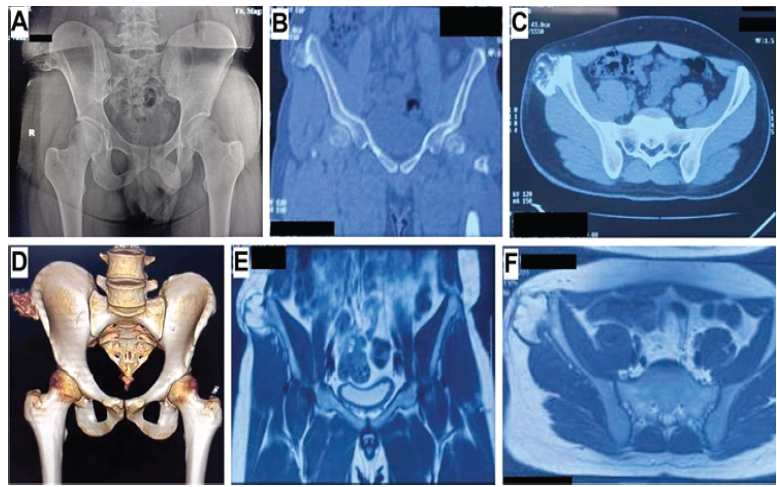

A pelvic radiograph revealed skeletal maturity (Risser grade 5). The presence of a radio-opaque, rounded mass arising from the outer table of the anterior third of the right iliac wing just posterior to the ASIS was noted (Fig. 4).

Figure 4: Pre-operative radiologic evaluation of the second patient. (a) Anteroposterior radiograph of the pelvis with both hips, (b) computed tomography image of the pelvis, coronal section, (c) computed tomography image of the pelvis, transverse section, (d) computed tomography image of the pelvis, three-dimensional reconstruction, (e) magnetic resonance imaging of the pelvis, coronal section, and (f) magnetic resonance imaging of the pelvis, transverse section (Potential patient identifiers have been blacked out).

Computed tomography and MRI were suggestive of an osteochondroma; a well-defined pedunculated lesion arising from and continuous with the underlying ilium was noted (Fig. 4). The mass was globular and measured approximately 4.5 × 3.6 × 4.2 cm. Its pedicle was 2 cm wide. A thin cartilaginous cap measuring a maximum of 6 mm in thickness, with no focal thickening or heterogeneity, was noted. The iliotibial band was displaced laterally due to the mass. No adjacent collection or bursa formation was noted, nor were there signs of adjacent neurovascular compression or pelvic lymphadenopathy.

In view of his painful hip movements and the resulting functional limitation, surgery was advised. Following spinal anesthesia, in the lateral position, a linear incision was made along the iliac crest directly over the visible mass. The soft-tissue covering the tumor was dissected until the cartilaginous cap was exposed. The surrounding musculature was retracted, and the pedicle of the tumor was exposed. En bloc resection of the tumor mass through the base of the pedicle along with a periosteal margin of 0.5 cm was performed using curved osteotomes. Hemostasis was achieved by covering the bleeding bone with bone wax. Adequacy of resection was confirmed under fluoroscopy. The wound was closed in layers. Histopathologic examination confirmed the preoperative diagnosis of osteochondroma and showed the presence of hyaline cartilage with a fibrous perichondrial covering over osseous tissue (Fig. 5). The post-operative period was uneventful. There was no tumor recurrence at 1 year postoperatively (Fig. 6).

Figure 5: Histopathologic appearance of the second patient’s tumor (Hematoxylin and Eosin). (a) At ×10 magnification, a cartilaginous cap lined by perichondrium is seen to be contiguous with bone (b) At ×40 magnification, a thin cartilage cap is noted along with trabecular bone, enchondral ossification is noted.

Figure 6: Post-operative anteroposterior pelvic radiograph of the second patient (Potential patient identifiers have been blacked out).

Osteochondromas are described as bony projections enveloped within a cartilaginous cover, arising along the external surface of bone [9,10]. They generally arise from an immature skeleton, predominantly consist of bone, and grow from their cartilaginous segment [9]. Although osteochondromas are considered by some as developmental pseudotumors, they are generally classified as benign neoplasms [9,10]. Despite their solitary presentation on most occasions, the association of hereditary multiple exostosis with mutations in the EXT1 and EXT2 genes bears testimony to this school of thought [4]. Observation and expectant conservative management are generally considered adequate for most solitary lesions, since they may spontaneously regress [4,9]. However, en bloc excision is considered the standard of care for symptomatic patients with pain, functional limitation, and/or compression of adjacent vital structures [1]. Osteochondromas of the pelvis are atypical and infrequent. Several of these have been reported to arise around the ischium [11,12], pubic rami [13,14], the hip joint [15,16], or in proximity with the sacrum [17,18]. Iliac osteochondromas are extremely rare, with few case reports in the literature. Most of these have been reported along the region of the iliac crest or the outer table of the ilium [1,2,3,4,5,6,7]. The location of the tumor in our second patient was similar to these cases, and surgery in the lateral position was fairly straightforward due to its easy and relatively safe accessibility. Although the need for anterior abdominal wall reconstruction has been reported following excision of such lesions on rare occasions, especially when they are sessile or when radical resection is carried out [4,5], such was not the case for our patient. Magalhães et al. [8] reported a rare case of pelvic osteochondroma along the inner table of the ilium in an 18-year-old boy. Despite its small size, it caused compression of the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve and resulted in meralgia paresthetica; the patient was advised surgery following failed conservative management but declined and was lost to follow-up. The location of the tumor in our first patient was also along the inner table of the ilium, but more posterior than the one reported by Magalhães et al. [8]. Despite the general norm of delaying surgery till attainment of skeletal maturity to mitigate the possibility of tumor recurrence, he was advised surgery due to the location of the tumor in close proximity with vital intrapelvic viscera and neurovascular structures. Surgery for this patient differed from that of the second, and the supine position was preferred for better access. The possibility of peritoneal injury and of the need for abdominal muscle reconstruction was acknowledged, and a general surgeon was available on standby throughout the procedure. However, gentle finger dissection of the anterior abdominal musculature, ready access to the tumor intraoperatively, and its pedunculated morphology rendered surgery uneventful. The diagnosis of an uncomplicated osteochondroma is generally unambiguous on clinical and radiologic assessment, and histopathologic evaluation seldom alters the course of management [19]. Although frequently asymptomatic, patients with these tumors do carry the risk of developing pain or compression of adjacent vital structures including neurovascular bundles due to continued progression in size, and of malignant transformation nevertheless [8,20,21]. The authors, therefore, believe that serial monitoring is adequate in most asymptomatic patients with isolated osteochondromas. However, when patients are symptomatic, or when the tumor lies in close proximity with vital structures, surgery with adequate planning may be more appropriate. Excision of pelvic osteochondromas can be challenging depending on the size and location of the tumor, and a patient-specific approach should be employed. The contrast in the management of inner table versus outer table osteochondromas of the ilium is illustrated through the two cases reported herein.

Regardless of the presence or absence of symptoms, excision of pelvic osteochondromas may be necessary in patients where the tumor is increasing in size and is located adjacent to vital structures. Surgery can be challenging in these cases, especially in skeletally immature patients. Meticulous pre-operative planning with attention to the tumor location, optimal patient position, avoidance of physeal injuries, and a multi-disciplinary approach can yield satisfactory outcomes.

Osteochondromas may rarely present over the inner or outer table of the ilium. In case of enlarging tumors in the vicinity of vital adjacent structures, appropriately planned surgical excision can be safe and effective, even for skeletally immature patients.

References

- 1. Sun J, Wang ZP, Zhang Q, Zhou ZY, Liu F, Yao C, et al. Giant osteochondroma of ilium: A case report and literature review. Int J Clin Exp Pathol 2021;14:538-44. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 2. Jain MJ, Kapadiya SS, Mutha YM, Mehta VJ, Shah KK, Agrawal AK. Unusually giant solitary osteochondroma of the ilium: A case report with review of literature. J Orthop Case Rep 2023;13:42-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 3. Loganathan K, Vasudevan P, Krishnan A, Arunachalam N, Manivannan A. Solitary osteochondroma in uncommon sites- a rare case report. J Orthop Case Rep 2025;15:166-70. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 4. Zamir M, Ahmed N, Iqbal F, Kamal SW. Sessile pelvic osteochondroma: A rare case that required abdominal wall reconstruction after excision. J Ayub Med Coll Abbottabad 2023;35:174-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 5. Olivero AA, Laxague F, Jorge FD, Sadava EE. Reconstruction of the abdominal wall after radical resection of pelvic osteochondroma. Cir Esp (Engl Ed) 2022;100:303. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 6. Thomas C, Sanderson B, Horvath DG, Mouselli M, Hobbs J. An unusual case of solitary osteochondroma of the iliac wing. Case Rep Orthop 2020;2020:8831806. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 7. Kokavec M, Gajdoš M, Džupa V. Osteochondroma of the iliac crest: Case report. Acta Chir Orthop Traumatol Cech 2011;78:583-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 8. Magalhães LV, Massardi FR, Pereira SA. Pelvic osteochondroma causing meralgia paresthetica. Neurol India 2019;67:928-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 9. De Souza AM, Bispo Júnior RZ. Osteochondroma: Ignore or investigate? Rev Bras Ortop 2014;49:555-64. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 10. Khurana J, Abdul-Karim F, Bovee JV. Osteochondroma. In: Fletcher CD, Unni KK, Mertens F, editors. Pathology and Genetics of Tumours of Soft Tissue and Bone. Lyon: IARC Press; 2002. p. 234-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 11. Trager RJ, Prosak SE, Getty PJ, Barger RL, Saab ST, Dusek JA. Ischial osteochondroma as an unusual source of pregnancy-related sciatic pain: A case report. Chiropr Man Therap 2022;30:45. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 12. De Moraes FB, Silva P, Do Amaral RA, Ramos FF, Silva RO, De Freitas DA. Solitary ischial osteochondroma: An unusual cause of sciatic pain: Case report. Rev Bras Ortop 2014;49:313-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 13. Sharma D, Mahendra M, Seth A. Pedunculated osteochondroma of inferior pubic ramus: A report of a rare case. Cureus 2025;17:e82546. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 14. Gökkuş K, Aydın AT, Sağtaş E. Solitary osteochondroma of ischial ramus causing sciatic nerve compression. Eklem Hastalik Cerrahisi 2013;24:49-52. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 15. Fuentes GO, Fuentes EJ, Sonora SG, Vertti RD. Intra-articular osteochondroma of the hip. Total hip replacement after tumor resection in a young adult – a case report. J Orthop Case Rep 2024;14:42-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 16. Makhdom AM, Jiang F, Hamdy RC, Benaroch TE, Lavigne M, Saran N. Hip joint osteochondroma: Systematic review of the literature and report of three further cases. Adv Orthop 2014;2014:180254. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 17. Bobinski L, Tachtaras E, Hedström E. Minimal-invasive, image guided, 360-degree resection of ilio-lumbo-sacral ostechondroma, planned on the 3D model in a child with hereditary multiple ostechondroma (HMO). Eur Spine J 2025;34:643-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 18. Kim WJ, Kim KJ, Lee SK, Choy WS. Solitary pelvic osteochondroma causing L5 nerve root compression. Orthopedics 2009;32:922. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 19. Wall LB, Clever D, Wessel LE, McDonald DJ, Goldfarb CA. The role of routine pathologic assessment after pediatric osteochondroma excision. J Pediatr Orthop 2024;44:513-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 20. Zheng L, Zhang HZ, Huang J, Tang J, Liu L, Jiang ZM. Clinicopathologic features of osteochondroma with malignant transformation. Zhonghua Bing Li Xue Za Zhi 2009;38:609-13. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 21. Herget GW, Kontny U, Saueressig U, Baumhoer D, Hauschild O, Elger T, et al. Osteochondroma and multiple osteochondromas: Recommendations on the diagnostics and follow-up with special consideration to the occurrence of secondary chondrosarcoma. Radiologe 2013;53:1125-36. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]