We should not forget a possibility of synovial osteochondromatosis accompanied by leg length discrepancy in the case of children.

Dr. Junya Shimizu, Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Sapporo Medical University School of Medicine, South-1, West-16, Chuo-ku, Sapporo, 060-8543, Japan. E-mail address: jshimizu@sapmed.ac.jp

Introduction: Synovial chondromatosis (SC) is very rare among children. We are aware of no reports of patients with SC accompanied by leg length discrepancy (LLD).

Case Report: We describe a case of synovial osteochondromatosis of a 7-year-old boy complicated by LLD. We performed epiphysiodesis of the distal femur and arthroscopic resection of loose bodies and total synovectomy. Three years after surgery, LLD had been corrected and there was no sign of recurrence.

Conclusion: Physicians should be aware of synovial osteochondromatosis complicated by LLD in childhood and take radiographs of the whole length of lower legs when this condition is suspected.

Keywords: Synovial osteochondromatosis, leg length discrepancy, knee joint, child.

Synovial chondromatosis (SC) is an unusual condition characterized by the formation of multiple hyaline cartilage nodules in joints, tendon sheaths, and bursae [1]. It is reported that the knee is the most involved joint. X-ray shows no radiopaque bodies in 5–30% of SC cases [2]. In cases when calcification cannot be seen on radiographs, MRI is useful and typically shows hyperintensity masses on T2-weighted images in affected joints, which reflect chondroid tissues. SC usually occurs between the third and fifth decades with a minor male predominance and it is unusual among children [2]. This report describes a rare case of a 7-year-old boy with SC of the knee, accompanied by leg length discrepancy (LLD).

Case: 7-year-old boy

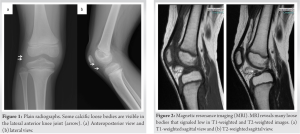

Chief complaint: Limitation of knee joint range of motion

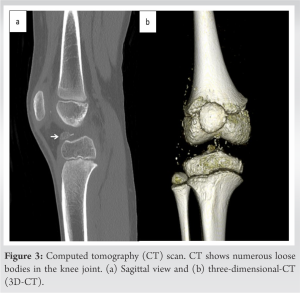

A 7-year-old boy was admitted to our hospital complaining of limited right knee flexion over a period of 6 months. He had swelling in his right knee, but no limping gait or tenderness. The right knee range of motion was limited to 0–120°. Radiographs revealed juxta-articular calcified or ossified loose bodies (Fig. 1).  MRI demonstrated joint effusion and small loose bodies in the anterior part of the knee joint (Fig. 2). Although we were concerned about radiation exposure, we conducted computed tomography (CT) scans to examine if the masses were calcified and determine their exact location. CT scan revealed multiple subtle calcifications in the joint (Fig. 3). We diagnosed him with SC of the knee. We opted for monitoring due to his lack of severe pain.

MRI demonstrated joint effusion and small loose bodies in the anterior part of the knee joint (Fig. 2). Although we were concerned about radiation exposure, we conducted computed tomography (CT) scans to examine if the masses were calcified and determine their exact location. CT scan revealed multiple subtle calcifications in the joint (Fig. 3). We diagnosed him with SC of the knee. We opted for monitoring due to his lack of severe pain.

When he was 10 years old, he returned to our hospital and radiographs showed a LLD of 2.2 cm (Fig. 4). The loose bodies had grown in both size and number. One year later, he developed severe right knee pain in addition to the 20° limitation in the right knee flexion. We decided to perform epiphysiodesis to treat the LLD and arthroscopic resection of the tumors.

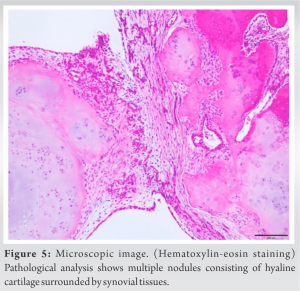

We first performed the epiphysiodesis of his distal right femur using an eight-Plate® (Japan Medicalnext Co., Ltd., Osaka, Japan). Four months after the epiphysiodesis, we performed the arthroscopic removal of the loose bodies. We found dozens of loose bodies in the affected joint. We performed total synovectomy and resection of the loose bodies with arthroscopy. Histopathological examinations of synovial tissues confirmed the diagnosis of SC (Fig. 5).

About 1 week postoperatively, the patient’s knee pain was greatly improved. Right knee range of motion was improved to 0–130°. Two years postoperatively, his LLD had been reduced to only 0.4 cm (right: 74.6 cm, left: 74.2 cm). We, thus, decided to remove the plate. At final follow-up, there was no clinically significant LLD, and he showed no signs of recurrence (Fig. 6).

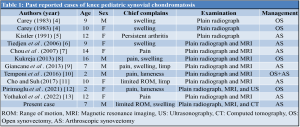

SC usually occurs in a single major joint, most commonly the knee, followed by the hip and elbow. SC has an incidence of one per 100,000 individuals among the general adult population, and about two in three patients are male [3]. It is extremely rare in children. A search of peer-reviewed papers reviewed only 12 patients with SC in childhood (Table 1) [4-13]. Open resection was performed in four of those cases, with arthroscopic surgery performed in the other nine. As of this writing, the authors are aware of no reports of SC accompanied by LLD. This is the first case report of SC with LLD in a pediatric patient.

LLD is a clinically important condition when it occurs in growing children. A wide range of causes have been reported, including congenital factors, vascular malformation, infection, tumors, and trauma. Importantly, inflammation often plays a role in LLD. Simon et al. [14] reported that 35 out of 51 patients (69%) in monoarticular and pauciarticular juvenile rheumatoid arthritis had LLD of 1.5 cm or more. LLD was more frequent among patients who experienced disease onset before the age of nine. Moued et al. [1512] reported 37 patients affected with oligoarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA). Of them, 9 patients (24.3%) were reported with LLD. One possible reason for this LLD is stimulation of the adjacent epiphyseal growth plate due to inflammation in the affected joint. Intra-articular steroid injection has been reported as an acceptable treatment option in JIA [16-19]. Sherry et al. [20] reported that intra-articular steroid injection (triamcinolone hexacetomide) was effective for the prevention of LLD in growing children with JIA. However, steroid injection into joints has some potential adverse effects such as skin atrophy, acute pain, irritation of the joint, and local calcification. Clinicians should be mindful of these potential risks when considering steroid injections.

Clinicians should be aware of SC as a potential, if rare, diagnosis, even among children. Before epiphyseal arrest, full-leg radiographs should be used when LLD is suspected.

We should be aware of synovial osteochondromatosis complicated by LLD in childhood and take radiographs of the whole length of lower legs when this condition is suspected.

References

- 1.Milgram JW. Synovial osteochondromatosis: A histopathological study of thirty cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1977;59:792-801. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 2.Maurice H, Crone M, Watt I. Synovial chondromatosis. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1988;70:807-11. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 3.Davis RI, Hamilton A, Biggart JD. Primary synovial chondromatosis: A clinicopathologic review and assessment of malignant potential. Hum Pathol 1998;29:683-8. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 4.Carey RP. Synovial chondromatosis of the knee in childhood. A report of two cases. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1983;65:444-7. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 5.Kistler W. Synovial chondromatosis of the knee joint: A rarity during childhood. Eur J Pediatr Surg 1991;1:237-9. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 6.Tiedjen K, Senge A, Schleberger R, Wiese M. Synovial osteochondromatosis in a 9-year-old girl: Clinical and histopathological appearance. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2006;14:460-4. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 7.Chou PH, Huang TF, Lin SC, Chen YK, Chen TH. Synovial chondromatosis presented as knocking sensation of the knee in a 14-year-old girl. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2007;127:293-7. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 8.Kukreja S. A case report of synovial chondromatosis of the knee joint arising from the marginal synovium. J Orthop Case Rep 2013;3:7-10. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 9.Giancane G, Tanturri de Horatio L, Buonuomo PS, Barbuti D, Lais G, Cortis E. Swollen knee due to primary synovial chondromatosis in pediatrics: A rare and possibly misdiagnosed condition. Rheumatol Int 2013;33:2183-5. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 10.Temponi EF, Mortati RB, Mortati GM, Mortati LB, Sonnery-Cottet B, de Carvalho Júnior LH. Synovial chondromatosis of the knee in a 2-year-old child: A case report and review of the literature. JBJS Case Connect 2016;6:e71. [Google Scholar | PubMed]