Maternal fibula as a bone graft for the management of congenital pseudoarthrosis of tibia is a better and cheaper alternative than BMP and allogenic cadaveric bone graft.

Dr. Anudeep Manne, Department of Orthopaedics, ESIC Medical College Hospital, Hyderabad - 500 038, Telangana, India. E-mail: dr.anudeepmanne@gmail.com

Introduction: Congenital pseudoarthrosis tibia (CPT) is a relatively rare disease, characterized by anterolateral bowing of the tibia, non-union, and limb length discrepancy. Various surgical treatments have been described in literature for its management with differing favorable outcomes.

Case Report: In this report, we present a case of 3-year-old child with CPT of Crawford type IV, with associated fibular dysplasia. Maternal fibula was harvested and used as a bone graft and was stabilized by intra-medullary fixation. Complete union was achieved at 1 year after the primary surgery. No re-fractures were seen in a follow-up period of 2 years.

Conclusion: Using maternal fibula as an alternative to use as a bone graft in the management of congenital pseudoarthrosis tibia may prove beneficial. Moreover, it is cheaper and readily available and needs less surgical expertise when compared to its alternatives such as use of bone morphogenetic protein 7, allogenic cadaveric grafting, or use of vascularized fibular graft.

Keywords: Allograft, mother’s fibula, fixation, congenital pseudoarthrosis tibia.

Congenital pseudoarthrosis of tibia (CPT) is characterized by an area of segmental dysplasia in the tibia resulting in anterolateral bowing of the bone [1]. This can result in tibial non-union with limb shortening. The outcome of the condition is extremely unfavorable and, chances of fracture healing without intervention are remote [2]. The condition is relatively rare with an incidence of 1 in 150,000 births [3]. It is most commonly associated with neurofibromatosis type 1, an autosomal dominant condition [4]. According to the Crawford classification, the lesions associated with complete pseudoarthrosis with sclerotic edges and associated fibular dysplasia carry worse prognosis [5]. We present a case of 3-year-old child, who presented to us with Crawford type IV pseudoarthrosis tibia with associated fibular dysplasia. The child posed a challenge as there was a large segment of sclerosis within the tibia and high chances of having significant limb length discrepancy and angular deformity. The child was managed with a non-vascular maternal fibular graft which, to the best of our knowledge, has not been reported previously. Although, there are a few reports of maternal tibia being used as an on-lay graft and maternal periosteal grafting, reports of fibula being used with intra medullary fixation have not been found.

A 3-year-old male child presented to our outpatient department at ESIC Medical College and Hospital, Kalaburagi, Karnataka, India. At presentation, the child had an anterolateral bowing of the right leg with abnormal mobility present between the distal and proximal segments of the leg. The femoral length on the right side was 2 cm longer than the left, while the tibial segment was 6 cm shorter. There was a scar on the anterior aspect of the leg, due to some previous intervention attempted by some surgeon when the child was 2 years old (Fig. 1). However, no implant was placed and further details of the surgery were not available.

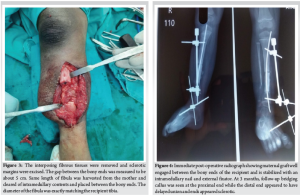

Radiographs showed the presence of a pseudoarthrosis at the junction of middle and lower 1/3rd of the right leg, with sclerotic margins of the bony ends (Fig. 2). The fracture was complete, and there was an anterolateral deformity between the fractured ends. The lower 1/3rd of fibula was also dysplastic. According to the Crawford classification, it was of type IV. Magnetic resonance imaging showed the presence of soft-tissue interposition between the fractured ends and computed tomography scan showed the presence of well-formed pseudoarthrosis. Considering that the bony edges were tapering and sclerotic, we anticipated that a large segment of the bone had to be removed to get good bleeding in the bony margins. As, the child was only 3 years old, getting adequate native bone to bridge the gap was difficult. The only option left to us was to do a maternal bone transfer as cadaveric allograft facility is not available in our setup. Parents were explained about the expected problems, and available options. Mother consented for the transfer of her fibula to bridge the gap. Two different surgical teams operated on two different tables. One team performed the fibular graft harvesting, while the other team comprising the author performed the procedure on the child. Surgical exposure revealed, frank non-union with sclerotic bone margins, and thick fibrotic tissue interposition. The fibrotic tissue was cleared thoroughly. The tapering bony edges were resected until good bleeding bone was visible. The gap between the resected bony edges was about 5 cm (Fig. 3).

The maternal fibula was completely denuded of soft-tissue attachments and intramedullary canal was reamed to clear all the marrow. Maternal fibula measuring exactly 5 cm was placed between the bone ends and stabilized with an intramedullary nail. Antigrade titanium elastic nail was passed starting from the lateral side. Additional iliac crest graft form the child was placed adjacent to the fibular ends (Fig. 4). External fixator was applied to provide additional stability. Wound closure was done in layers and an above knee posterior slab was applied.

Postoperatively wound inspection was done t 2nd day and the patient was put on daily calcium supplements and weekly dose of bisphosphonates (35 mg of alendronate). The patient was discharged on the 5th day and was kept in regular monthly follow-ups. X-rays were done every month to look for the progress of the union. On the 3rd follow-up after surgery, the proximal end of the fibular graft showed signs of healing but the distal end showed signs of non-union (Fig. 4). Three months after the index surgery, bone marrow injection was injected adjacent to the distal end of the fibula and an additional pin was passed retrograde, across the ankle through the fibular graft. One year after the primary surgery, good healing of the pseudoarthrosis was achieved (Fig. 5). Child started walking bearing weight after 1 year, that is, at the age of 4 years. Finally, there was a shortening of <5 mm and there was no angular deformity. The patient was kept in observation for 2 years and there were no complications or re-fractures noted.

Through this report, we have described an alternative treatment for CPT in young children with frank pseudoarthrosis and long segment bony sclerosis. Such children if intervened surgically would require a lot of bone graft between the fractured ends. Maternal fibula would be ideal in such situation as the diameter of fibula actually match the diameter of pediatric tibia. It additionally provides good structural support until the process of bony remodeling is complete. It is a cheaper readily available and needs less surgical expertise when compared to its alternatives such as use of bone morphogenetic protein 7, allogenic cadaveric grafting, or use of vascularized fibular graft.

Management of pseudoarthrosis tibia has always been a challenge for clinician with no definitive standardized method with proven results. Our experimentation with maternal fibula as an alternative for bone graft may prove beneficial for the management. Since we have found success in one case, it requires further research and scientific evidence to make it a standardized procedure in congenital pseudoarthrosis tibia.

References

- 1.Andersen KS. Radiological classification of congenital pseudarthrosis of the tibia. Acta Orthop Scand 1973;44:719-27. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 2.Mahnken AH, Staatz G, Hermanns B, Gunther RW, Weber M. Congenital pseudarthrosis of the tibia in pediatric patients: MR imaging. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2001;177:1025-9. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 3.Hefti F, Bollini G, Dungl P, Fixsen J, Grill F, Ippolito E, et al. Congenital pseudarthrosis of the tibia: History, etiology, classification, and epidemiologic data. J Pediatr Orthop Part B 2000;9:11-5. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 4.El-Rosasy MA. Congenital pseudarthrosis of the tibia: The outcome of a pathology-oriented classification system and treatment protocol. J Pediatr Orthop Part B 2020;29:337-47. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 5.Crawford AH. Neurofibromatosis in children. Acta Orthop Scand Suppl 1986;218:1-60. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 6.Boyd HB. Pathology and natural history of congenital pseudarthrosis of the tibia. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1982;166:5-13. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 7.Gutmann DH, Aylsworth A, Carey JC, Korf B, Marks J, Pyeritz RE, et al. The diagnostic evaluation and multidisciplinary management of neurofibromatosis 1 and neurofibromatosis 2. JAMA 1997;278:51-7. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 8.Karol LA, Haideri NF, Halliday SE, Smitherman TB, Johnston CE 2nd. Gait analysis and muscle strength in children with congenital pseudarthrosis of the tibia: The effect of treatment. J Pediatr Orthop 1998;18:381-6. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 9.Johnston CE 2nd. Congenital pseudarthrosis of the tibia: Results of technical variations in the Charnley-Williams procedure. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2002;84:1799-810. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 10.Shah H, Rousset M, Canavese F. Congenital pseudarthrosis of the tibia: Management and complications. Indian J Orthop 2012;46:616-26. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 11.Weber M. Neurovascular calcaneo-cutaneus pedicle graft for stump capping in congenital pseudarthrosis of the tibia: Preliminary report of a new technique. J Pediatr Orthop Part B 2002;11:47-52. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 12.Ansari MT, Gautam D, Kotwal PP. Mother’s fibula in son’s forearm: Use of maternal bone grafting for aneurysmal bone cyst not amenable to curettage - a case report with review of literature. SICOT J 2016;2:18. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 13.Palanisamy JV, Balachandran R. Incorporation of allogenous fibular graft in pediatric humerus following segmental resection. IOSR J Dent Med Sci 2016;7:1-4. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 14.Salunkhe AA, Raiturker PP. Benign lytic lesions of the bone, staging and management correlations. Indian J Orthop 2003;37:8. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 15.Langer F, Czitrom A, Pritzker K, Gross A. The immunogenicity of fresh and frozen allogeneic bone. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1975;57:216-20. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 16.Paley D. Congenital pseudarthrosis of the tibia: Biological and biomechanical considerations to achieve union and prevent refracture. J Child Orthop 2019;13:120-33. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 17.Heikkinen ES, Poyhonen MH, Kinnunen PK, Seppänen UI. Congenital pseudarthrosis of the tibia. Treatment and outcome at skeletal maturity in 10 children. Acta Orthop Scand 1999;70:275-82. [Google Scholar | PubMed]