Vertebral fracture is a rare but possible complication during ECV for AF.

Dr. Matteo Spadini, Department of Orthopaedic and Traumatology, University of Perugia, Perugia, Italy. (06129). E-mail: dr.spadini.matteo@gmail.com, matteo.spadini@specializzandi.unipg.it

Introduction: Cardioversion for atrial fibrillation (AF) is considered a well-known and safe procedure. However, there are potential complications described associated to this procedure. Bone sequalae or fractures are not cited in consent forms neither in Italy nor in the United States. Nevertheless, cases of vertebral fractures have been reported after multiple defibrillations for ventricular tachycardia and all these cases involved relatively young patients.

Case Report: We present the case of a 44-year-old Caucasian male patient with no comorbidities who underwent cardioversion to restore sinus rhythm from AF. The patient complained of acute dorsal back pain immediately after the cardioversion procedure. The patient informed the cardiologist about the back pain, but no clear explanation for the symptom was provided. Three weeks later, the patient underwent a magnetic resonance and was subsequently diagnosed with a cardioversion procedure-related sixth thoracic (T6) vertebral body fracture.

Conclusion: Vertebral compression fracture should be included in the differential diagnoses for severe back pain after cardioversion procedures. Investigation with standard X-ray or, in doubt, with a magnetic resonance imaging of the painful segment is advisable. In addition, this possible complication should be considered in the informed cardiological consent for the cardioversion procedure even though extremely rare.

Keywords: Vertebral fracture, electrical cardioversion, atrial fibrillation, acute back pain.

Electrical cardioversion (ECV) has been extensively used to treat patients affected by supraventricular and ventricular tachycardia since its first application in 1959. This procedure presents a low, but not negligible risk of complications. Systemic thromboembolism, hypotension, bradyarrhythmias, life-threatening ventricular tachycardia, major bleeding, and pulmonary edema can occur in patients undergoing elective or urgent ECV [1-3]. Notably, bone injuries or fracture-related sequelae are routinely not considered in differential diagnosis in patients presenting with back pain after cardioversion. This oversight may contribute to inadequate assessment and management of these conditions. Furthermore, this latter complication is not cited in consent forms neither in Italy nor in the United States, despite a few cases of vertebral fractures are reported in literature.

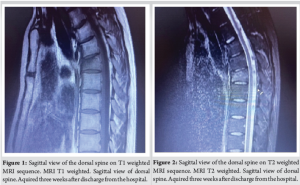

We report the case of a 44-year-old Caucasian male patient (187 cm height, 78 kg weight) without any significant medical history presented to the Emergency Department complaining about palpitations and dyspnea. Electrocardiography showed the presence of high-rate AF without hemodynamic impairment. Blood examinations were performed at admission: aspartate and alanine aminotransferase, creatine, bilirubin, potassium, sodium, amylase, lipase, C reactive protein, leukocytes, hemoglobin, and platelet levels were within limits (Table 1). An initial rate control approach with beta intravenous metoprolol was performed and the patient was admitted to the Cardiology Department. He underwent transthoracic and transesophageal echocardiography that excluded the presence of major cardiac structural abnormalities or intracavitary thrombosis. Thereafter, the cardiologist planned and performed an ECV by use of a single biphasic 100 J direct current (DC) shock with anteroposterior leads position after appropriate sedation (intravenous five mg midazolam bolus). The patient complained of acute back pain just after the first cardioversion procedure. Pain was partially responsive to standard painkillers and worsened in standing position with partial bilateral thoracic irradiation. Regarding the pain progression, the patient began experiencing rachialgia immediately after recovery from anesthesia on the day of the first procedure; this pain persisted and worsened following the second and third cardioversions, which were associated with two cardiac ablations performed in the following days. The patient was discharged from the hospital after the third cardioversion with complete resolution of the AF and no evidence of procedure-related complications. Persisting the dorsal pain after hospital discharge, the general practitioner prescribed a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the painful thoracic spine. Three weeks after discharge, MRI revealed a T6 (sixth thoracic) vertebral body fracture (Fig. 1-3). Given the timing between the cardioversion procedure and the onset of pain, the fracture was considered a post-cardioversion procedure complication. It was a wedge-shaped fracture with superior endplate major involvement and bone edema. No posterior vertebral body wall interruption occurred and the patient was completely free from neurological symptoms. Treatment with bisphosphonates and cholecalciferol supplements was initiated. After 3 months of conservative treatment, the pain disappeared, leaving a temporary residual paravertebral muscular contracture. The patient is a non-smoker with no bone disorders, aside from slight osteopenia observed in computerized bone mineralometry, and no previous history of spine fractures or back pain. He was not on any medication before AF. His past medical history includes fractures from significant trauma (nasal septum, cheekbone, third finger of the hand) and cervical radiculopathy 20 years ago, which had resolved. Furthermore, he has previously not experienced any back pain. No falls or trauma were reported during the hospital stay.

The patient of this case report was treated for AF by use of a single biphasic 100 J DC shock and began to experience thoracic rachialgia just after the first cardioversion procedure. After 3 weeks of persisting pain, MRI revealed a T6 vertebral fracture. Since ECV was the only anamnestic feature that could be potentially correlated, we hypothesized an association between the vertebral fracture and a massive muscular contracture induced by the ECV that was performed on the patient three weeks earlier. DC cardioversion shock can be delivered by monophasic or biphasic current. The shock can be synchronized with the peak of the QRS complex (synchronized cardioversion) in case of supraventricular arrhythmias or stable ventricular tachycardia. In case of non-synchronized DC shock, the procedure is defined as electrical defibrillation. Many studies demonstrated that biphasic shock waveforms presented a more favorable efficacy and safety profile compared to monophasic shock [4-6]. ECV can be performed by positioning the electrical pads in anteroposterior or anterolateral position [7,8]. The use of anteroposterior electrode position has been associated with higher rates of successful ECV in the literature [9]. Overall, cardioversion is considered a safe procedure. However, some complications are described and should be explained to the patients through a consent form. Notably, sequelae related to bone injuries or fractures are not taken into account in differential diagnosis in patients presenting with back pain after cardioversion and are not cited in consent forms neither in Italy nor in the United States. The occurrence of a thoracolumbar compression fracture in a cardioverted otherwise healthy patient, with no predisposing factor for bone weakness, is documented in literature in only two complete and accessible case reports described by Koda in 2020 and Wilsmore in 2018. In his case, Koda reported that a single 200 J DC shock was performed with pads placed on anteroposterior sites in order to treat AF with elevated ventricular rate [10]. In the other report, Wilsmore documented the administration of a single biphasic shock during ECV for AF [11]. Cases of vertebral fractures were also reported in a different clinical context that is multiple defibrillations for ventricular tachycardia [12,13]. All these cases involved relatively young patients without any major orthopedic or systemic risk factor for spontaneous bone fractures. Moreover, this rare complication occurs both after monophasic and biphasic shocks and it appears to have no relation with the energy applied during the shock. Few case reports in literature describe fractures involving upper limbs (more common) and lower limbs caused by electrical discharge [14-17]; this mechanism is typical in HV (high voltage) electric shock because more likely to happen [18], although fractures caused by LV (low voltage) are described [19]. In a not therapeutic case report, vertebral fracture has been related to the electric weapon used by police enforcement [20]. Few case reports regarding fractures associated to electric shock exist in literature, although they are not fully accessible [21-23]. Many authors describe the mechanism as a prolonged and uncontrolled contracture of muscles that leads to the compression fracture, mainly in fragile (e.g., children) and osteoporotic patients. Moreover, there is the evidence that tetanic muscle spasm in seizures can cause fractures. Other known complications in seizures or electric shocks are glenohumeral dislocation, even bilateral. The spastic reflex induced by electric energy during cardioversion may account for superior vertebral endplate fracture with anterior wedging and posterior wall integrity, that is the significant finding in Koda’s and Wilsmore’s case reports as well as in our patient. The flexion contracture mechanism acts on the anterior wall of the vertebra; differently from the well-known mechanism of axial compression occurring when the force of impact is vertical along the axis of the spine, as in a fall onto the feet or buttocks. The risk of fracture depends on voltage amplitude and frailty of the patients, nevertheless a low voltage energy can cause fracture in young and healthy patients. Our case and what reported in the literature suggest that a post-procedure X-ray should be considered in all patients with back pain who have undergone a cardioversion procedure. If the X-ray is negative for fracture, an MRI should be prescribed if the patient continues to complain of back pain. Neurological involvement must be ruled out since has been reported in literature, even though extremely rare [10]. Regarding patient’s information, existing the possibility of such complications, it should be taken into account in the informed consent for cardioversion even though extremely rare.

Vertebral compression fracture is a rare yet possible complication after ECV. The risk of fracture depends on the voltage amplitude and frailty of the patients. Nevertheless, a low voltage energy can cause a vertebral fracture even in young and healthy patients. Furthermore, even though very rare, vertebral fracture should be taken into account as a consequence of cardioversion for AF. This leads to the consideration that an X-ray in patients with back pain who have undergone cardioversion is advisable. Vertebral compression fracture should be included in the differential diagnoses for severe back pain after cardioversion procedures. In such cases, the patient should be investigated with a standard X-ray or, in doubt, with an MRI of the painful segment. In addition, this possible complication should be considered in the informed cardiological consent for the cardioversion procedure even though extremely rare.

In the case of acute back pain after cardioversion procedure, the patient should be studied with a standard X-ray and, in the doubt, an MRI for detecting a very rare but possible vertebral compression body fracture. Such complication should be considered and mentioned in the informed cardiological consent for cardioversion.

References

- 1.Brandes A, Crijns HJ, Rienstra M, Kirchhof P, Grove EL, Pedersen KB, et al. Cardioversion of atrial fibrillation and atrial flutter revisited: Current evidence and practical guidance for a common procedure. Europace 2020;22:1149-61. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 2.Grönberg T, Nuotio I, Nikkinen M, Ylitalo A, Vasankari T, Hartikainen JE, et al. Arrhythmic complications after electrical cardioversion of acute atrial fibrillation: The FinCV study. Europace 2013;15:1432-5. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 3.Hansen ML, Jepsen RM, Olesen JB, Ruwald MH, Karasoy D, Gislason GH, et al. Thromboembolic risk in 16 274 atrial fibrillation patients undergoing direct current cardioversion with and without oral anticoagulant therapy. Europace 2015;17:18-23. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 4.Page RL, Kerber RE, Russell JK, Trouton T, Waktare J, Gallik D, et al. Biphasic versus monophasic shock waveform for conversion of atrial fibrillation: The results of an international randomized, double-blind multicenter trial. J Am Coll Cardiol 2002;39:1956-63. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 5.Schneider T, Martens PR, Paschen H, Kuisma M, Wolcke B, Gliner BE, et al. Multicenter, randomized, controlled trial of 150-J biphasic shocks compared with 200- to 360-J monophasic shocks in the resuscitation of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest victims. Optimized response to cardiac arrest (ORCA) investigators. Circulation 2000;102:1780-7. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 6.Inácio JF, Da Rosa Mdos S, Shah J, Rosário J, Vissoci JR, Manica AL, et al. Monophasic and biphasic shock for transthoracic conversion of atrial fibrillation: Systematic review and network meta-analysis. Resuscitation 2016;100:66-75. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 7.Walsh SJ, McCarty D, McClelland AJ, Owens CG, Trouton TG, Harbinson MT, et al. Impedance compensated biphasic waveforms for transthoracic cardioversion of atrial fibrillation: A multi-centre comparison of antero-apical and antero-posterior pad positions. Eur Heart J 2005;26:1298-302. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 8.Siaplaouras S, Buob A, Rötter C, Böhm M, Jung J. Randomized comparison of anterolateral versus anteroposterior electrode position for biphasic external cardioversion of atrial fibrillation. Am Heart J 2005;150:150-2. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 9.Kirchhof P, Eckardt L, Loh P, Weber K, Fischer RJ, Seidl KH, et al. Anterior-posterior versus anterior-lateral electrode positions for external cardioversion of atrial fibrillation: A randomised trial. Lancet 2002;360:1275-9. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 10.Koda EK. Lumbar compression fracture caused by cardioversion. Am J Case Rep 2020;21:e927064. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 11.Wilsmore B, May A, Fitzgerald J. Vertebral fracture resulting from cardioversion for atrial fibrillation. J Interv Card Electrophysiol 2018;53:391. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 12.Okel BB. Vertebral fracture from cardioversion shock. JAMA 1968;205:369. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 13.Giacomoni P, Cremonini R, Cristoferi E, Guardigli C, Gulinelli E, Matarazzo V, et al. Frattura vertebrale da cardioversione elettrica [Vertebral fracture caused by electric cardioversion]. G Ital Cardiol 1987;17:543-5. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 14.Özer H, Baltaci G, Selek H, Turanli S. Opposite-direction bilateral fracture dislocation of the shoulders after an electric shock. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2005;125:499-502. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 15.Rhee SJ, Reddy GK, Holder DS, Haddad FS. Sub-trochanteric fracture of the femur following electric shock. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2008;90:W1-3. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 16.Rana M, Banerjee R. Scapular fracture after electric shock. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2006;88:3-4. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 17.Kechagias VA, Katounis CA, Badras SL, Notaras I, Badras LS. Bilateral posterior fracture-dislocation of the shoulder after electrical shock treated with bilateral hemiarthroplasty: A case report. Malays Orthop J 2022;16:146-9. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 18.Gehlen JM, Hoofwijk AG. Femoral neck fracture after electrical shock injury. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg 2010;36:491-3. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 19.Peyron PA, Cathala P, Vannucci C, Baccino E. Wrist fracture in a 6-year-old girl after an accidental electric shock at low voltages. Int J Legal Med 2015;129:297-300. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 20.Winslow JE, Bozeman WP, Fortner MC, Alson RL. Thoracic compression fractures as a result of shock from a conducted energy weapon: A case report. Ann Emerg Med 2007;50:584-6. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 21.Rajam KH, Reddy DR, Sathyanarayana K, Rao DM. Fracture of vertebral bodies due to accidental electric shock. J Indian Med Assoc 1976;66:35. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 22.Putti E, Tatò FB. A case of fracture of the 5th cervical vertebra caused by electric shock. Chir Organi Mov 1989;74:153-4. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 23.Meschan I, Scruggs JB, Calhoun JD. Convulsive fractures of the dorsal spine following electric-shock therapy. Radiology 1950;54:180-93. [Google Scholar | PubMed]