We report a case of atlanto-axial rotation fixation that required internal fixation after repeated recurrences. In such cases, which have a congenital element, it is possible that patients may not respond to standard conservative treatment and early internal fixation should be considered

Dr. Ryunosuke Fukushi, Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Sapporo Medical University School of Medicine, S1 W16, Sapporo, Hokkaido, 060-8543, Japan. E-mail: ryunosuke_fukushi_521@yahoo.co.jp

Introduction: Most cases of atlanto-axial rotatory fixation (AARF) respond well to conservative treatment. Few reports have described initial management strategies. Almost no cases of AARF with recurrence requiring internal fixation have been reported. Here, we describe a case of recurrent AARF requiring internal fixation.

Case Report: A 5-year-old boy presented with a history of 22q.11.2 deletion syndrome, DiGeorge syndrome, congenital left-sided clubfoot, and periodic vomiting. He was referred to a local pediatrician with neck pain and torticollis and was prescribed analgesics. After 5 days of no improvement, he was referred to a local pediatric orthopedic hospital where he was diagnosed with AARF (Fielding classification type III). The patient was then referred to our department for traction and orthotic therapy. Computed tomography revealed no deformity of the atlanto-axial articular surface and no evidence of bony fusion between the left and right posterior arches of the atlas. Following conservative treatment, the patient’s neck pain and torticollis improved, and imaging confirmed the deformity had corrected. He was discharged on day 32. The symptoms recurred on day 42, and although traction and orthotic therapies were repeated, no improvement was observed. A halo vest was applied on day 59 after symptom onset. As the deformity was corrected, the halo vest was removed on day 94 and the patient continued to wear an orthosis. The patient recurrenced on day 104 and internal fixation was performed on day 120. Two 2.4-mm hollow screws were inserted using the Magerl method. No recurrence was observed at 213 days after onset, and bone union was confirmed by imaging test, and the brace was removed.

Discussion: Factors contributing to the intractability and recurrence of AARF include laxity and dysfunction of the transverse ligament. In this case, the latter was suspected because of the lax ligament structure. The patient did not undergo atlanto-axial fusion at age 5 years and vertebral bone hypoplasia was observed. Patients with a congenital element may not respond to standard conservative treatment. Thus, if the dislocation is left untreated, the lateral atlanto-axial joint may completely dislocate and drop, causing myelopathy. Thus, early internal fixation is considered desirable in such cases.

Conclusion: In cases of AARF involving congenital factors, patients may not respond to standard conservative treatment. Early internal fixation should therefore be considered.

Keywords: Atlanto-axial rotation fixation, internal fixation, recurrence., halo-vest fixation.

Atlanto-axial rotatory fixation (AARF) is a condition in which the atlantoaxial joint becomes fixed in a rotary deformity, resulting in painful torticollis. AARF can occur following minor trauma, head and neck surgery, upper respiratory tract infections, or other cervical inflammation. However, the cause remains unknown in many cases. Because most cases of AARF respond well to conservative treatment, only a few reports have described initial treatment strategies. No further reports on recurrence of AARF or even cases that have progressed to internal fixation are available. In this report, we describe a case of AARF that recurred repeatedly and ultimately required internal fixation as well as a treatment strategy for such cases based on a review of the literature.

A 5-year-old boy presented with left congenital clubfoot and cyclic vomiting. The patient’s family history was unremarkable. During the course of treatment, this patient was diagnosed with 22q.11.2 deletion syndrome, DiGeorge syndrome. The patient presented mental retardation and achieved head control at 4 months, rollover at 5 months, sitting unaided at 10 months, walking with support at 18 months, and walking unaided at 23 months. His height and weight were 97.7 cm and 13.2 kg, respectively (Kaup index, 13.8). The patient developed right temporal headache, neck pain, and torticollis, and was seen by a local pediatrician and was diagnosed with myofascial neck pain, and progress was monitored using analgesics. When torticollis did not improve, the child was seen at the Children’s Medical Center 5 days after the onset of symptoms. After a thorough examination, AARF was diagnosed, and the child was referred to our department for specialized care 15 days after symptom onset. On computed tomography (CT), the atlas vertebra was rotated right anteriorly and left posteriorly, and the patient was classified as having Fielding type III. No atlanto-axial articular surface deformities were observed. No evidence of bony fusion between the left and right posterior arches of the atlas was visible (Fig. 1a, b, c, d). On examination, the patient was placed in right lateral flexion and left rotation in a positive cock-robbin position. The ranges of neck motion were as follows: Flexion, 50°; extension, 50°; rotation (right/left) 20/50°; and lateral flexion (right/left) 40/10°. Pain was observed during neck motion, but no neurological abnormalities, such as paralysis, muscle weakness, or abnormal reflexes were observed.

The patient was admitted to the hospital on the day of consultation, and traction and orthotic therapies were provided. As the patient was able to achieve reduction and the neck pain improved, he was discharged 32 days after symptom onset and scheduled for outpatient follow-up (Fig. 1e, f, g, h). It was decided that the patient would continue wearing the brace. Subsequently, despite wearing a brace, the torticollis recurred without any particular trigger (upper respiratory infection or history of trauma). At the time of the outpatient follow-up 42 days after the onset of symptoms, a detailed examination revealed evidence of a recurrence. On the CT images, the patient presented the same condition as before, with rotation of C1 to the right anterior and left posterior, and a Fielding classification of type III. No atlanto-axial articular surface deformities were observed. No bony fusion was present between the left and right posterior arches of the atlas (Fig. 1i, j, k, l). He was admitted to the hospital on day 52 post-symptom onset and traction therapy was resumed, although reduction was not achieved. A halo vest was applied on day 59 post-symptom onset. This reduction was confirmed using intraoperative CT (Fig. 2).

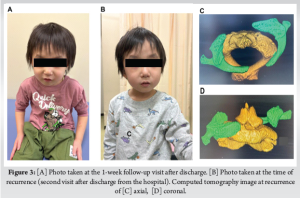

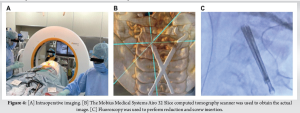

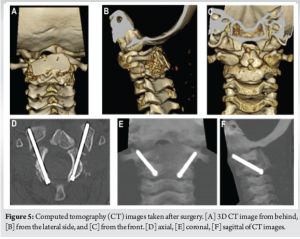

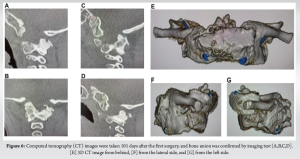

No further complications occurred, and the halo vest was removed 94 days after symptom onset. The halo vest was worn for 35 days. The hello vest was removed with the brace still in place. The pin insertion site was then sutured. Post-operative radiographs were used to verify the reduction. A CT scan 1 day after surgery (removal of the halo vest) confirmed that the reduction position was maintained, and the patient was discharged from the hospital. At the 1-week follow-up visit after discharge, there was no evidence of recurrence (Fig. 3a). However, 3 days after the follow-up appointment, the patient experienced AARF recurrence, with no particular upper respiratory infection or trauma episodes (Fig. 3b, c, d). In this case, the decision was made to perform a reoperation at a facility with a good understanding of AARF, 120 days after the onset of symptoms. Internal fixation was then performed. The location of the vertebral artery was confirmed pre-operatively. Reduction and screw insertion were planned. Fixation was performed under general anesthesia using a Mayfield indicator. Internal fixation was performed by inserting two 2.4 mm hollow screws in accordance with the Magerl method (Fig. 4). The surgery was completed without any complications. The post-operative radiographs were also considered fine. However, on the CT images obtained after surgery, it was determined that the right screw was in the optimal position, but the left screw was slightly shorter than it should have been slightly inserted into the lateral mass, although the trajectory was not a problem. To ensure complete bone fusion, the screw on the left side was replaced with a longer screw using a guidewire (Fig. 5). No recurrence was observed at 213 days after onset (101 days after the first surgery), and bone union was confirmed by imaging test, and the brace was removed (Fig. 6).

The initial treatment of AARF is based on conservative management, such as traction therapy and cervical orthoses. Cervical hard collar immobilization should be performed first and if there is no improvement after 1 week, Glisson traction should be applied promptly [1,2]. Glisson traction should be continued for at least 2 weeks. Thus, there are a number of reports on initial treatment strategies for cervical rotation immobilization, but few reports on cases of recurrent AARF. In Europe and America, Subach et al., reported recurrence in 6 of 20 (30%) pediatric patients with AARF and found no correlation between age, sex, or cause of onset and recurrence [3]. In contrast, the only report involving Japanese people is the report by Yamada et al., which states that the recurrence rate was 8% [4]. In the present case, conservative treatments, such as traction therapy and a cervical collar, were used as at the initial onset, although no reduction was achieved. Initially, the cause of the cervical rotation was unknown in several cases. Many reports have described its occurrence after upper respiratory tract infection, head and neck surgery under general anesthesia, or trauma, but the underlying mechanisms are unknown [5]. The atlanto-axial joint in children has anatomical features, such as a flat articular surface, a wedge-shaped anterior vertebral body, and a hypoplastic odontoid process with loose ligamentous structures [6]. As a result, impingement of the joint capsule and synovium can easily occur, even during physiological rotation, leading to the development of the condition. Further, if CT images show a deformity of the articular surface, it is desirable to induce remodeling of the atlanto-axial joint by performing halo vest fixation under general anesthesia [7-9]. In this case, the lateral atlanto-axial joint in a young child was thought to be prone to atlanto-axial subluxation. In other words, the inclination is often stronger, with a tendency to fall in the outward and inferior directions (in adults, the coronal and sagittal planes are almost horizontal). In addition, although the transverse diameter of the C2 spinal canal and the width between the lateral masses of C1 are almost equal in adults, the lateral masses were more lateralized in children, as in this case [1]. It is also possible that transverse ligament dysfunction was involved. This classification is based on the degree of anterior subluxation of the atlas, and this condition tends to become more intractable as the degree of subluxation increases from 1 to 3. If treatment is prolonged, even in cases of Fielding type I or II, stress is placed on the transverse ligament, causing relaxation and dysfunction, which makes it easier to progress to Fielding type III, resulting in a loss of stability and an increased risk of recurrence [2]. The factors involved in the intractability and recurrence of AARF are (i) facet deformity (if the rotational deformity is not corrected within approximately 4–6 weeks, bony deformity will occur in the lateral atlanto-axial joint), (ii) asymmetrical relaxation and contracture of soft tissues (such as the joint capsule) on the left and right sides, and (iii) relaxation and dysfunction of the transverse ligament [2]. If facet deformity is clearly present and the reduction cannot be maintained, halo vest therapy or surgical therapy should be considered. In this case, there was no obvious facet deformity and the CT scan obtained after traction showed that the atlanto-axial joint had shifted slightly forward from the axis. This shape is similar to that often observed in children with atlanto-axial subluxations. It is not known whether this is due to congenital factors or the result of remodeling due to the atlanto-axial joint being in a forward position, due to the laxity of the atlanto-axial joint; however, these may be causative factors (Fig. 2). If the rotation is prolonged, even in the absence of bony deformity, asymmetrical contracture and relaxation of soft tissues may occur, which can lead to recurrence. In this case, although there was no deformity of the articular surface at age 5 years, fusion of the anterior and posterior arches of the atlas was not observed. It is thought that ossification between the left and right posterior arches of the atlas occurs by the age of 3 years. In addition, the anterior arch and lateral masses on either side fuse by approximately age 7, and the atlas takes on a complete, ring-like, ossified form [10-12], which may be related to recurrence, but further case studies are needed. Furthermore, this case also showed vertebral hypoplasia. In such cases where there are congenital factors, there is a possibility that the patients will not respond to standard conservative treatment. If the dislocation is left untreated, the lateral atlanto-axial joint may completely dislocate and fall, causing myelopathy; thus, early internal fixation was considered for this patient.

Here, we report a case of AARF that required internal fixation after repeated recurrences. In such cases, which have a congenital element, it is possible that patients may not respond to standard conservative treatment and early internal fixation should be considered.

If a congenital factor is present, standard conservative treatment may be ineffective. If the dislocation is left untreated, the lateral atlanto-axial joint may dislocate completely and fall, causing myelopathy. Therefore, early internal fixation should be considered in such cases.

References

- 1. Ohtani K, Matsumoto N, Fujimoto M, Inagaki H, Kitsuda K, Kaida M, et al. Atlanto-axial rotatory fixation in children comparison of clinical findings and outcomes by etiology. J Jpn Paediatr Orthop Assoc 2014;23:407-15. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 2. Phillip WA, Hensinger RN. The management of rotatory atlanto-axial subluxation in child. J Bone Joint Surg 1989;71:664-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 3. Subach BR, Mclaughlin MR, Albright AL, Pollack IF. Current management of pediatric atlantoaxial rotatory subluxation. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1998;23:2174-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 4. Yamada K, Sato K, Wakioka T A study of the conservative treatment algorithm for the fixation of the atlanto-axial rotation in children. Orthop Traumatol 2014;63:501-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 5. Tauchi R, Imagama S, Ito Z, Ando K, Muramoto A, Matsui H, et al. Atlantoaxial rotatory fixation in a child after bilateral otoplastic surgery. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol 2014;24 Suppl 1:S289-92. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 6. Rahimi SY, Stevens EA, Yeh DJ, Flannery AM, Choudhri HF, Lee MR. et al. Treatment of atlantoaxial instability in pediatric patients. Neurosurg Focus 2003 15;15(6) [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 7. Ishii K, Toyama Y, Nakamura M, Chiba K, Matsumoto M. Management of chronic atlantoaxial rotatory fixation. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2012;37:E278-85. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 8. Tauchi R, Imagama S, Kanemura T, Yoshihara H, Sato K, Deguchi M, et al. The treatment of refractory atlanto-axial rotatory fixation using a halo vest: Results of a case series involving seven children. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2011;93:1084-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 9. Kashii M, Masuhara K, Kaito T, Iwasaki M. Rotatory subluxation and facet deformity in the atlanto-occipital joint in patients with chronic atlantoaxial rotatory fixation: Two case reports. J Orthop Case Rep 2017;7:59-63. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 10. Calvy TM, Segall HD, Gilles FH, Bird CR, Zee CS, Ahmadi J, et al. CT anatomy of the craniovertebral junction in infants and children. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 1987;8:489-94. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 11. Karwacki GM, Schneider JF. Normal ossification patterns of atlas and axis: A CT study. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2012;33:1882-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 12. Pang D, Thompson DN. Embryology and bony malformations of the craniovertebral junction. Childs Nerv Syst 2011;27:523-64. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]