High-quality imaging and meticulous pre-operative planning are essential when approaching rare intra-articular trochlear fractures. In selected cases, medial epicondyle osteotomy provides safe and enhanced visualization of the fracture fragment, facilitating accurate anatomic reduction and stable fixation

Dr. Maulik Kothari, Department of Orthopaedics, Seth GS Medical College and KEM Hospital, Mumbai, Maharashtra, India. E-mail: mkothari8@gmail.com

Introduction: Isolated trochlear fractures of the distal humerus are rare and often underreported.

Case Report: We present a case of a 35-year-old female who sustained such a fracture after falling onto a flexed elbow. Initially managed conservatively, she later required surgery due to persistent pain and limited motion. Imaging revealed an anterosuperiorly displaced osteochondral fragment, necessitating open reduction and internal fixation via medial epicondyle osteotomy. Two titanium screws secured the fragment, achieving articular congruency. Twelve months post-operative, the patient had a Mayo Elbow performance index score of 100.

Conclusion: This case emphasizes the importance of recognizing and managing isolated trochlear fractures effectively.

Keywords: Trochlea, elbow, medial epicondyle osteotomy.

Trochlea, Greek for “pulley,” is a medial osteochondral element at the distal humerus. It articulates distally with the ulna and is covered by articular cartilage with a 270° arc. Due to its strategic position in the trochlea of the ulna with the absence of muscular and ligamentous attachments, it is protected from the prevalent shear forces that are significant in causing distal humerus fractures. Consequently, isolated trochlear shear fractures are rarely reported in medical literature.

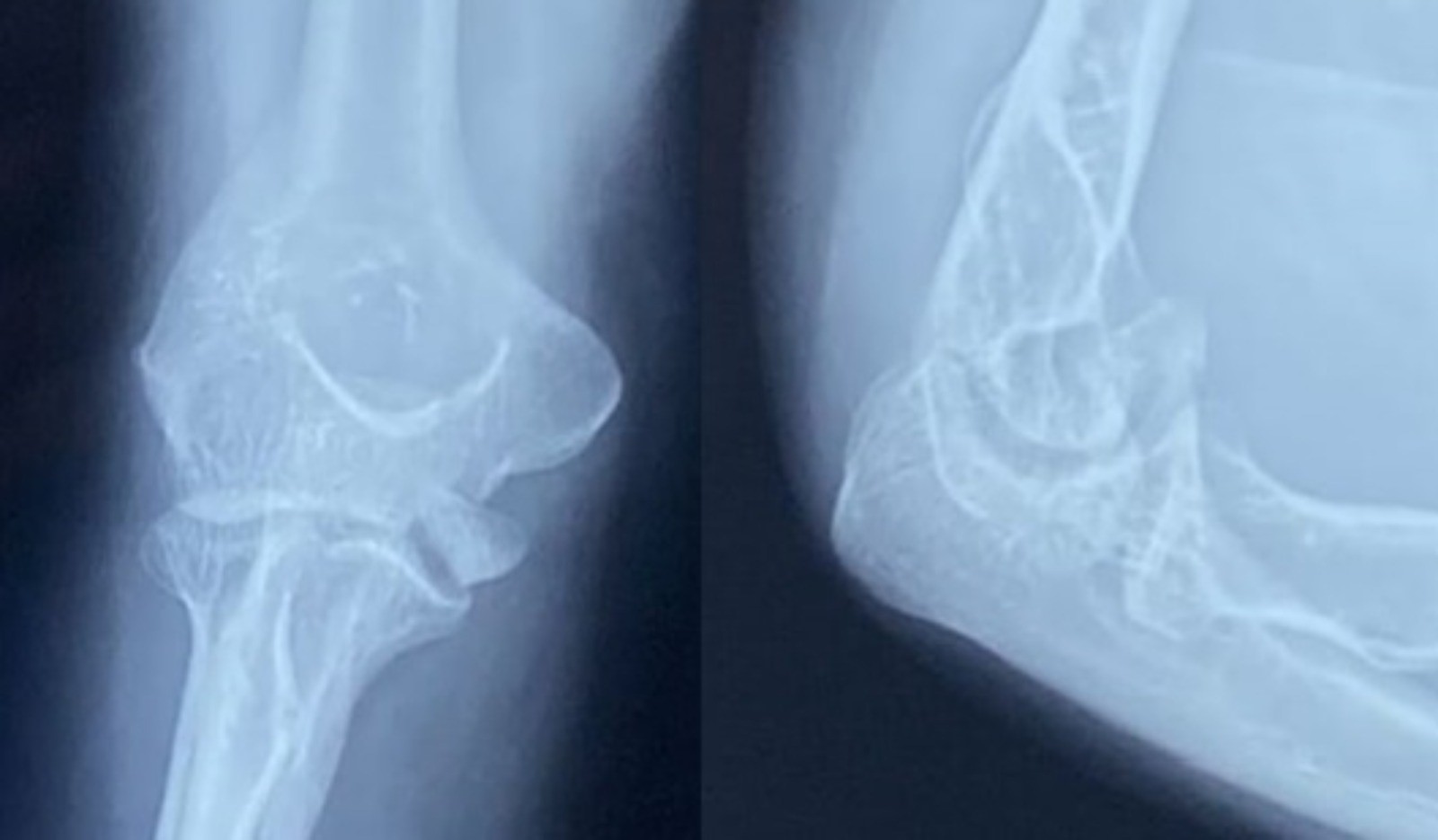

We present the case of a 35-year-old female who presented 3 weeks post-traumatic injury to her elbow. She had a fall on the flexed elbow with force directed through the olecranon tip proximally. She was initially managed with a splint in 90° elbow flexion and forearm supination. She was advised conservative management for the fracture, including immobilization for 8 weeks followed by gradual physical therapy; however, she presented to us due to constant pain and restricted elbow range. On examination, she exhibited swelling and tenderness over the medial elbow without wounds or distal neurovascular deficit. Plain radiographs of her elbow showed a half-moon-shaped fragment displaced anterosuperiorly with irregular ulnohumeral articulation in the lateral X-ray. No dislocation of the elbow joint or the radial head was noted. These findings were corroborated on subsequent computed tomography (CT) scans (Fig. 1 and 2).

Figure 1: Anteroposterior and lateral radiographs showing anterosuperiorly displaced trochlear fragments.

Figure 2: Computed tomography scan sections showing the displaced trochlear fragment marked in a circle on (a) axial, (b) coronal, and (c) sagittal cuts.

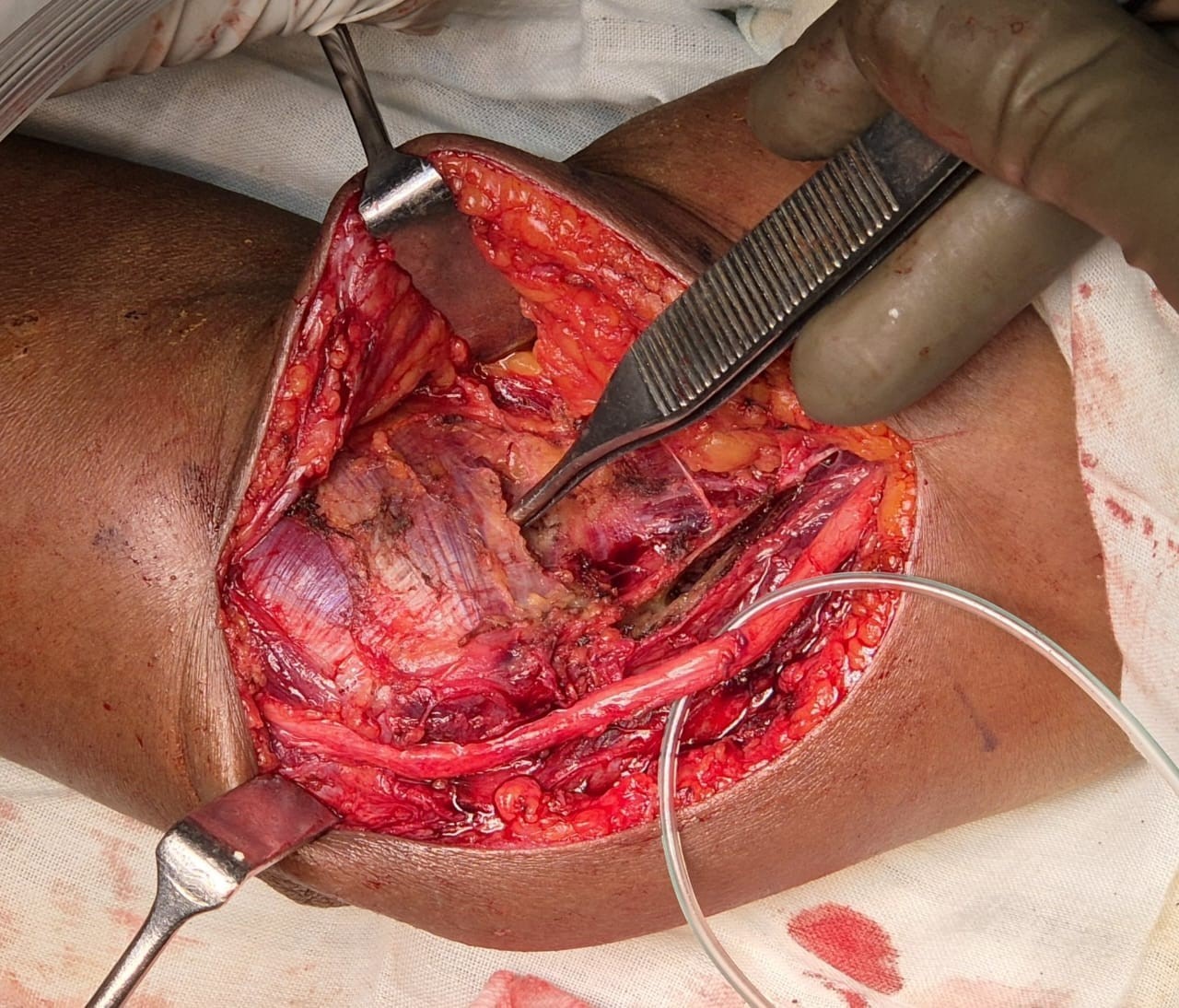

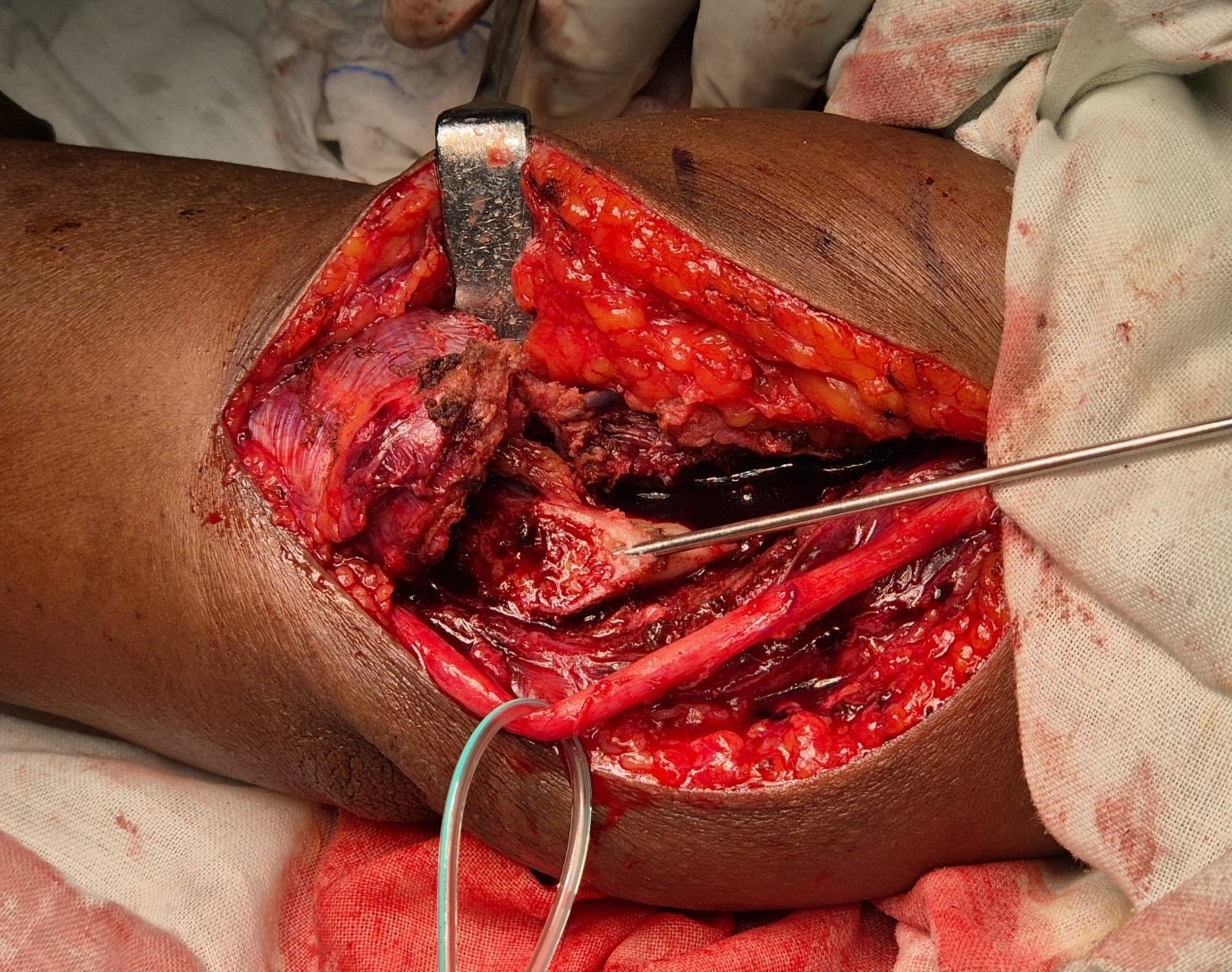

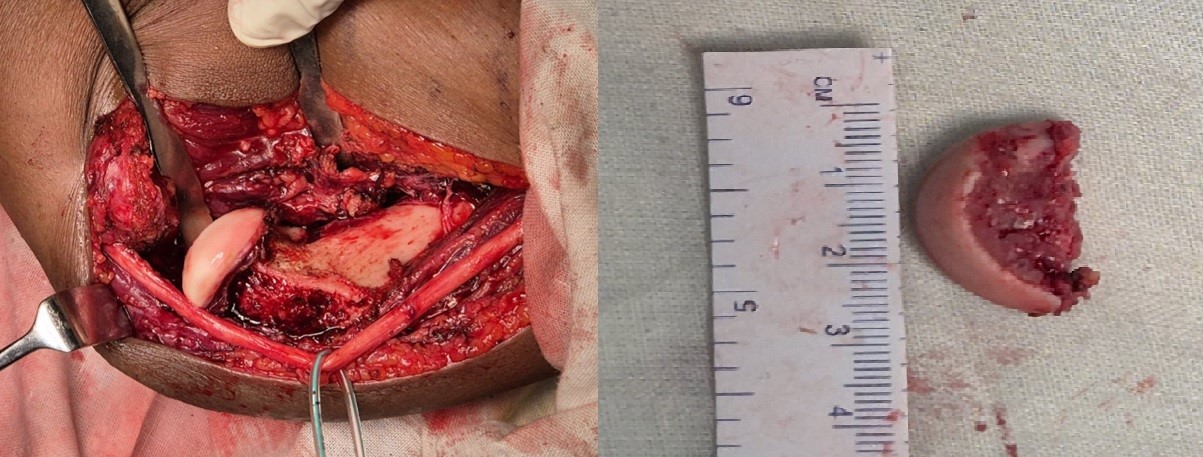

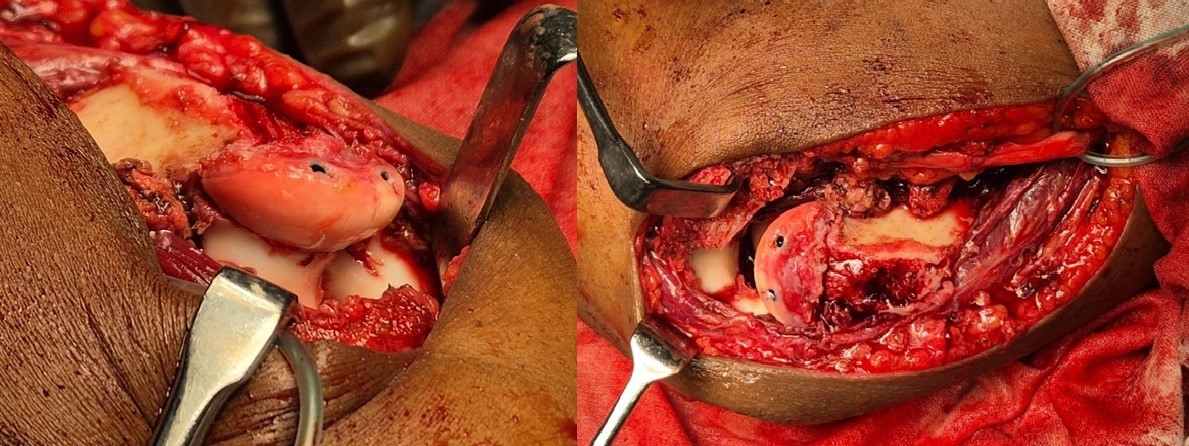

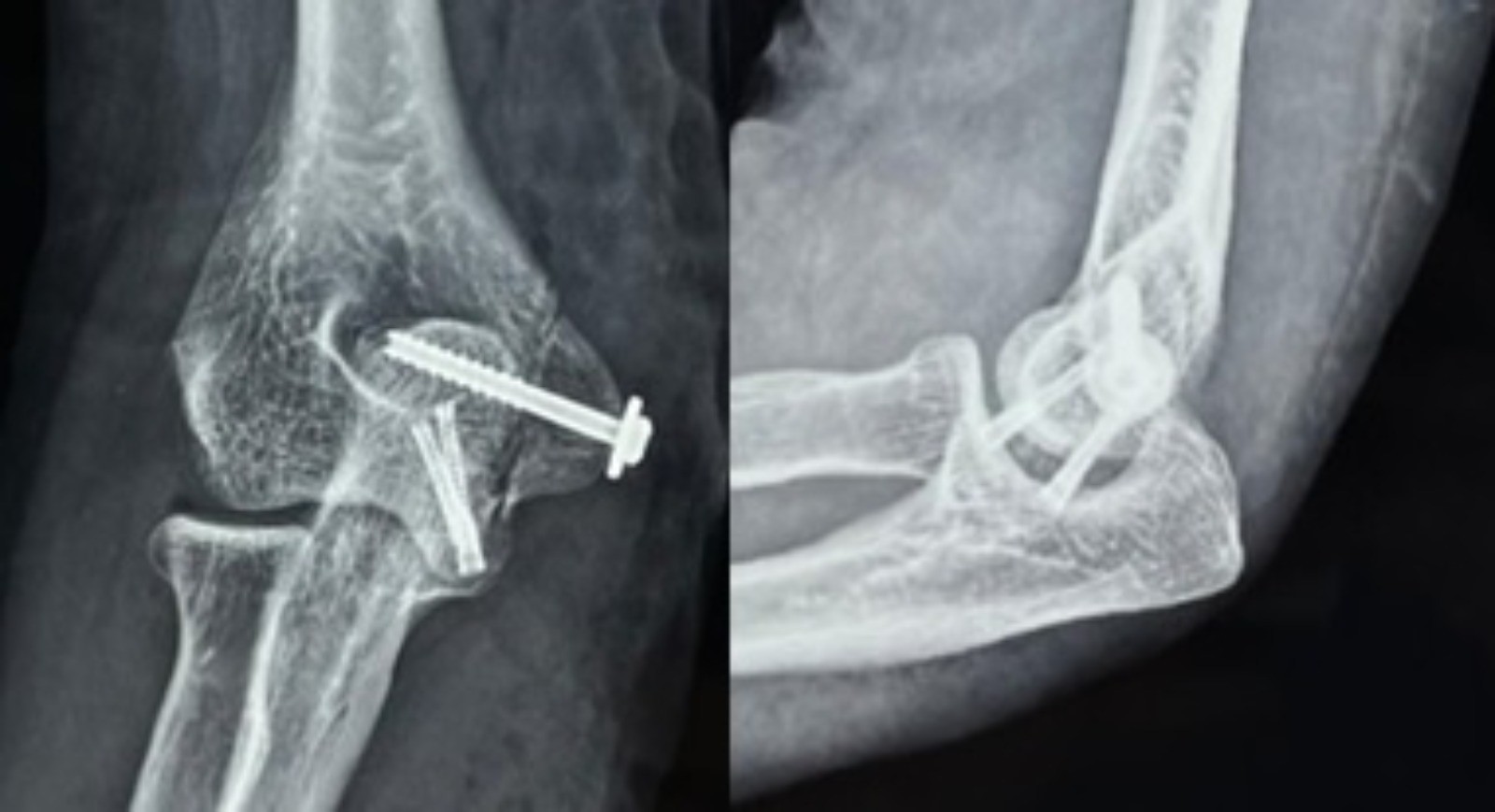

The patient was planned for open fixation of the fracture to maintain articular congruency and provide an acceptable range for her limb. A standard medial approach to the elbow was taken. The plane was developed between the brachialis and triceps proximally and the pronator teres and brachialis distally after isolating the ulnar nerve (Fig. 3). Given the difficulty in accessing the fracture fragment, which was positioned anterior to the medial condyle, an osteotomy of the medial epicondyle was performed, preserving the common flexor origin (Fig. 4). The capsule was dissected, preserving the medial collateral ligament (MCL) to expose the articular surface. The large osteochondral fragment of the trochlea of size 2.4 cm × 1.2 cm was found displaced anterosuperiorly without significant loss of articular cartilage (Fig. 5). Fracture margins were freshened, and anatomy was delineated. Two titanium 3.3 mm variable pitch headless screws were used to fix the fracture fragment to the trochlear bed from directions inferomedial to superolateral, carefully measuring the depth and direction of screw insertion to avoid penetrating the olecranon fossa using image guidance. Articular congruency was achieved (Fig. 6 and 7). The medial epicondyle osteotomy was fixed with standard cannulated 4 mm partially threaded cancellous screws with a washer, preserving the common flexor origin, and the joint capsule was closed. The elbow range was checked under fluoroscopy and found satisfactory. Medial approach closure was done.

Figure 3: The interval between brachialis and pronator (marked by forceps) and the isolated ulnar nerve.

Figure 4: Medial epicondyle osteotomy done to approach the fracture fragment.

Figure 5: The displaced fragment as seen medio-laterally and on table measurement of the fragment.

Figure 6: The fragment was reduced and fixed with a headless screw in its anatomical position.

Figure 7: Post-operative radiographs showing anatomically reduced trochlear fragment with a congruent ulnohumeral articulation.

The patient was followed up at week 2, week 6, month 3, and month 6. The range was satisfactory, and the patient achieved a Mayo Elbow performance index score of 91 at 6 months. Plain radiographs at 12 months demonstrate union and articular congruency (Fig. 8).

Figure 8: Radiographs 12 months post-operative showing union and articular congruency.

Isolated trochlear fractures were first reported by Laugier in 1853, bearing his eponymous name: Laugier’s fracture, with subsequent scarce mention in subsequent literature. It has been classified as AO/OTA B3.2 for distal humerus fractures [1].

The divergent single-column theory [2] has been proposed as a possible mechanism for these injuries in young patients. It is hypothesized that when an axial load is applied to the proximal ulnohumeral joint, it drives into the trochlea, causing shearing, with the force subsequently propagating proximally to exit medially or laterally from either humeral column, creating a high single-column fracture. For isolated trochlear fractures to occur, the force has low energy, insufficient to travel to the humeral columns and cause their fracture. The capitellum is spared in this scenario, suggesting it was subjected to lesser force. The unique articulation of the ulnohumeral joint, combined with the anatomical flexion of the trochlear fragment in relation to the humeral shaft, allows different forces to be applied at different angles of flexion. Here, the anterosuperior displacement of the trochlea suggests that the shearing force was applied when the elbow was in flexion.

Worrell [3] reported a case of isolated trochlear injury in which the mode of trauma was a fall on an extended arm. This suggests an alternative mechanism of axial load transmission, as a fall on an extended arm typically leads to fractures of both the capitellum and trochlea. It may be theorized that the force through the radial head was insufficient, with the trochlear fragment bearing the brunt of the force through the coronoid, with insignificant transmission to the humeral columns.

When examining the patient, the range of motion and soft tissue, and neurovascular status should be carefully examined. The routine practice of investigating with CT scans is recommended to corroborate the findings of plain anteroposterior and lateral radiographs, reducing the incidence of missing articular discontinuity and comminution, thereby improving understanding of fracture anatomy and outcomes [4].

Management of the fracture should be operative until the fracture is undisplaced to avoid future arthritis, joint stiffness, and poor elbow function, as these fracture patterns and fragment sizing predispose it to early osteolysis and increased incidence of fragment avascular necrosis. The morphology and size of the fractured fragments drive the decision regarding the modality used for fracture fixation. Smaller fragments not amenable to fixation can be excised; larger fragments are ideally subjected to internal fixation.

Both standard medial and anterior approaches to the elbow can be used; however, our literature search revealed that the medial approach was preferred by most authors, allowing easier access without significant dissection.

The position of the fracture fragment, which was displaced anterosuperiorly, allowed for best visualization only after the medial condyle was removed from view. The direction of the fracture displacement guides whether an anterior approach, a medial approach without medial condyle osteotomy, or a medial approach with medial condyle osteotomy should be used to access the fracture fragment. Before proceeding with the osteotomy, the common flexor origin should be preserved. The capsule was dissected, maintaining the integrity of the MCL.

Kwan et al. [5] used a single Herbert screw in the anteroposterior direction to fix the fragment and achieve interfragmentary compression using the medial approach.

Sen et al. [6], in their case series of five cases, used 4 mm AO partially threaded cancellous screw fixation in three cases with large osteochondral fragments, whereas using Kirschner wires in two cases with smaller trochlear fragments. Zimmerman et al. [7] used a medial approach and two headless Herbert screws for fixation. Abbassi et al. [8] used two Herbert screws, one inserted from medial to lateral and the other from lateral to medial, breaching the articular cartilage but sinking the heads deep to prevent any further cartilage damage.

Das and Kumar [9] used the posterior approach to the humerus and fixed the laterally displaced fragment with headless screws after olecranon osteotomy.

The choice of implant used in the majority of cases was Herbert headless screws for larger fragments and K-wires for smaller. With the size of our fragment, we determined that headless screws offered the best fixation. Screws were inserted at the osteochondral junction, directed obliquely from medial to lateral and posteroinferiorly to anterosuperiorly, attaining compression perpendicular to the fracture site. Care should be taken to bury the screw heads beneath the articular cartilage to prevent implant-induced arthritis [10,11]. Herbert screws offer this additional advantage over cortical screws since they can be buried beneath the articular cartilage, reducing the risk of cartilage damage and subsequent arthritis, although a higher cost is an issue [12].

Excision of the trochlea is not recommended as it leads to considerable instability of the elbow joint, as seen in cadaveric studies [13]. Both capitellum and trochlea combine to achieve elbow stability. While excision of the capitellum may be considered in the presence of an intact collateral ligament, excision of the trochlea leads to multiplanar elbow instability.

All the cases our literature search had [14-17] good long-term follow-up and presented with favorable elbow range and Mayo Elbow Performance score ratings. Early mobilization of the elbow can be achieved with direct reduction and rigid fixation to prevent iatrogenic elbow stiffness and capsule contraction. A range of motion exercises should be started as soon as pain is tolerable. Passive range exercises should make way for active strength training with time.[18]

Isolated trochlear fractures are rare due to their protected position within the elbow joint, which helps prevent shearing. In suspected trochlear fractures, high-quality imaging with CT scans and 3D reconstruction should be performed to visualize the fragment in space and plan for surgery. The medial approach to the elbow is used, which necessitates the osteotomy of the medial epicondyle. The fracture fragment may be fixed with headless or Herbert screws, avoiding screw penetration into the olecranon fossa. Owing to the role of the trochlea in maintaining elbow stability, its anatomy should be respected, and the fracture should be open-reduced with rigid fixation to provide good elbow function and prevent the risk of arthritis. The early range should be started and supported with strength training.

When standard exposure is inadequate, medial epicondyle osteotomy helps achieve anatomic reduction and good elbow function.

References

- 1. Lawan Abdou A, El Aissaoui T, Lachkar A, Abdeljaouad N, Yacoubi H. A partial frontal fracture of the humeral trochlea: A case report. Cureus 2024;16:e56640. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 2. Kuhn JE, Louis DS, Loder RT. Divergent single-column fractures of the distal part of the humerus. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1995;77:538-42. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 3. Worrell RV. Isolated, displaced fracture of the trochlea. N Y State J Med 1971;71:2314-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 4. McKee MD, Jupiter JB, Bamberger HB. Coronal shear fractures of the distal end of the humerus. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1996;78:49-54. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 5. Kwan MK, Khoo EH, Chua YP, Mansor A. Isolated displaced fracture of humeral trochlea: A report of two rare cases. Inj Extra 2007;38:461-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 6. Sen RK, Tripahty SK, Goyal T, Aggarwal S. Coronal shear fracture of the humeral trochlea. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong) 2013;21:82-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 7. Zimmerman LJ, Jauregui JJ, Aarons CE. Isolated shear fracture of the humeral trochlea in an adolescent: A case report and literature review. J Pediatr Orthop B 2015;24:412-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 8. Abbassi N, Abdeljaouad N, Daoudi A, Yacoubi H. Isolated fracture of the humeral trochlea: A case report and review of the literature. J Med Case Rep 2015;9:121. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 9. Das D, Kumar A. Isolated trochlear fracture in an elderly lady: A rare and interesting case treated in a rural coal mines hospital. J Orthop Case Rep 2024;14:146-50. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 10. Jeevannavar SS, Shenoy KS, Daddimani RM. Corrective osteotomy through fracture site and internal fixation with headless screws for type I (hahn-steinthal) capitellar malunion. BMJ Case Rep 2013;2013:bcr2013009230. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 11. Bauer AS, Bae DS, Brustowicz KA, Waters PM. Intra-articular corrective osteotomy of humeral lateral condyle malunions in children: Early clinical and radiographic results. J Pediatr Orthop 2013;33:20-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 12. Yoshida S, Sakai K, Nakama K, Matsuura M, Okazaki S, Jimbo K, et al. Treatment of capitellum and trochlea fractures using headless compression screws and a combination of dorsolateral locking plates. Cureus 2021;13:e13740. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 13. Sabo MT, Fay K, McDonald CP, Ferreira LM, Johnson JA, King GJ. Effect of coronal shear fractures of the distal humerus on elbow kinematics and stability. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2010;19:670-80. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 14. Nakatani T, Sawamura S, Imaizumi Y, Sakurai A, Fujioka H, Tomioka M, et al. Isolated fracture of the trochlea: A case report. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2005;14:340-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 15. Oberstein A, Kreitner KF, Lowe A, Michiels I. Isolated fracture of the trochlea humeri following direct elbow trauma. Aktuelle Radiol 1994;4:271-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 16. Anwer S, Uddin S, Khalid H, Haq RU, Hamid A, Farhan M, et al. Isolated trochlear fracture of the humerus. Proc Shaikh Zayed Med Complex Lahore 2023;37:20-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 17. Lari A, Alrumaidhi Y, Martinez D, Ahmad A, Aljuwaied H, Alherz M, et al. Clinical outcomes and management strategies for capitellum and trochlea fractures: A systematic review. Orthop Res Rev 2024;16:179-97. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 18. Kazuki K, Miyamoto T, Ohzono K. Intra-articular corrective osteotomy for the malunited intercondylar humeral fracture: A case report. Osaka City Med J 2002;48:95-100. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]