This study highlights that age alone should not be considered a contraindication to total knee arthroplasty (TKA). Patients aged 70 years and older experienced significant functional improvement postoperatively, with mean Oxford Knee Score (OKS) improvements comparable to those of younger patients, despite a higher burden of comorbidities. The study further establishes that higher Charlson comorbidity index (CCI) scores and ASA grades are strongly associated with increased risk of readmission and mortality, emphasizing the critical role of pre-operative risk profiling and optimization in this age group.

Dr. Tarun Jayakumar, Sunshine Bone and Joint Institute, KIMS-Sunshine Hospitals, Hyderabad, Telangana, India. E-mail: tarunjaykumar@gmail.com

Introduction: Despite the increasing demand for total knee arthroplasty (TKA) in elderly patients, outcomes in this demographic remain uncertain due to their higher comorbidity burden and perioperative risks. This study aimed to assess and compare patient-reported outcomes (PROMs), readmission rates, and complications after primary TKA in elderly patients (aged 70 years or older at the time of surgery) versus a matched cohort of younger patients aged <70 years.

Materials and Methods: This was a retrospective review conducted on patients who underwent primary unilateral TKA between 2016 and 2021 at a high-volume tertiary center. Two age cohorts, patients aged ≥70 years and patients <70 years, were matched for gender and body mass index. Outcomes measured included PROMs using Oxford knee score (OKS), readmission rates, and complications at a minimum 1-year follow-up, and statistical analyses were performed.

Results: Of the 1028 elderly patients included, a readmission rate of 4.5% and a mortality rate of 2.4% were noted within the 1st year, compared to 1.07% and 0.6% in the younger cohort. Both elderly and younger patients showed significant improvement in OKS (mean improvements: 22.24 points in the elderly group and 19.81 points in the younger group). Patients with higher Charlson comorbidity index scores demonstrated a significantly increased risk of both readmission and mortality in both age groups (P < 0.001).

Conclusion: TKA provides significant functional improvement in patients aged 70 years or older, though they face higher risks of readmission and mortality. Pre-operative optimization of comorbidities and a tailored rehabilitation plan are essential to maximize benefits and minimize risks.

Keywords: Old age, functional outcomes, septuagenarian, complications, total knee arthroplasty, risk factors, Charlson comorbidity index.

Total knee arthroplasty (TKA) is a well-established and effective surgical intervention for treating end-stage arthritis of the knee joint. It consistently provides significant improvements in pain relief, functional mobility, and quality of life for patients suffering from primary osteoarthritis of the knee. Numerous factors, such as component or limb alignment, ligament balancing, and implant design, influence the functional outcomes after TKA [1,2,3,4,5]. However, the effect of patient age remains a relatively underexplored aspect. According to reports from the World Health Organization, the global average life expectancy in 2019 was 73.3 years, whereas the healthy life expectancy at birth was 63.7 years [6]. As life expectancy continues to increase, there is a corresponding rise in the number of patients seeking TKA for the management of advanced osteoarthritis [7]. By the year 2030, the demand for this procedure is projected to increase by 673%, reaching around 3.48 million procedures [8]. Nonetheless, concerns regarding the safety and outcomes of such surgical interventions in older patients persist, and this proportion is expected to grow as the population in this age group expands [9].

Advancements in perioperative care for TKA, including pre-operative optimization of comorbidities, multimodal analgesia, regional anesthesia, and enhanced recovery after surgery protocols, have contributed to a reduction in post-operative complications [10]. However, the outcomes for elderly patients undergoing TKA remain uncertain. While existing literature suggests that older adults may achieve knee scores comparable to those of younger patients during the 1st post-operative year, there is limited evidence on long-term follow-up, making it challenging to ascertain their longer-term outcomes [11,12]. Understanding key outcomes, such as post-operative pain and functional status beyond the initial recovery period, is critical to identify potential differences between elderly and younger cohorts. Furthermore, variability in reported complication rates in the literature remains a challenge, partly due to inconsistencies in recording methods, small sample sizes, limited follow-up durations, and the absence of appropriate comparator groups [12,13].

The primary aim of this study was to assess and compare patient-reported outcomes, readmission rates, and rates of patients achieving the minimum clinically important difference (MCID) (based on the Oxford knee score [OKS]) after primary TKA in elderly patients (aged 70 years or older at the time of surgery) versus an age-appropriate cohort of younger patients aged <70 years.

Following Institutional Ethics Committee approval (SIEC/2022/476), we conducted a review of prospectively collected Institute Joint Registry data of patients undergoing primary unilateral TKA, performed between 2016 and 2021 at a single high-volume tertiary center in India. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study, following ethical guidelines, and data were sourced from the institutional joint registry. Patients operated during this period were segregated into two groups. The first group included “elderly” patients aged 70 years or older with a minimum follow-up period of at least 1 year. The second group comprised an equal number of patients under the age of 70 years, matched for gender and body mass index (BMI), with the same minimum follow-up duration of 1 year. Data were sourced from the institutional registry database and patient case records for pre-operative and surgery details.

Inclusion criteria consisted of patients with available pre-operative anesthesia evaluations, including the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) classification and Charlson comorbidity index (CCI) scores. Patients with documented inflammatory arthritis, complex deformities, prior knee surgeries, revision TKAs, or those who underwent simultaneous or staged bilateral TKAs were excluded.

All surgeries were performed by a single senior surgeon using a standardized medial parapatellar approach under spinal anesthesia. Prophylactic antibiotics were administered as 1.5 g of cefuroxime for three doses. Standard post-operative deep vein thrombosis (DVT) prophylaxis was provided, and a uniform rehabilitation protocol was followed by all patients.

The patients who successfully finished their 1-year follow-up were contacted over the telephone by the author. The goal of this contact was to assess their functional outcomes using the OKS along with a structured questionnaire. In addition, data regarding readmissions and complications were collected. Readmissions, reoperations, and mortality rates were recorded for both 1-month and 1-year intervals, with causes for readmission categorized as either medical or surgical.

Patient-reported knee-specific outcome measures, such as the OKS, are routinely collected and documented in all cases. The OKS is initially recorded before surgery and after surgery at specified follow-up intervals of 3, 6, and 12 months and annually thereafter.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences software version 24.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). Continuous variables were summarized as means with standard deviations (SD), while categorical variables were presented as absolute and relative frequencies (percentages). Pre- and post-operative OKS were compared using a paired Student’s t-test for parametric data, whereas categorical data were analyzed using the Chi-squared test, with likelihood ratios calculated where appropriate. P < 0.05 was deemed statistically significant.

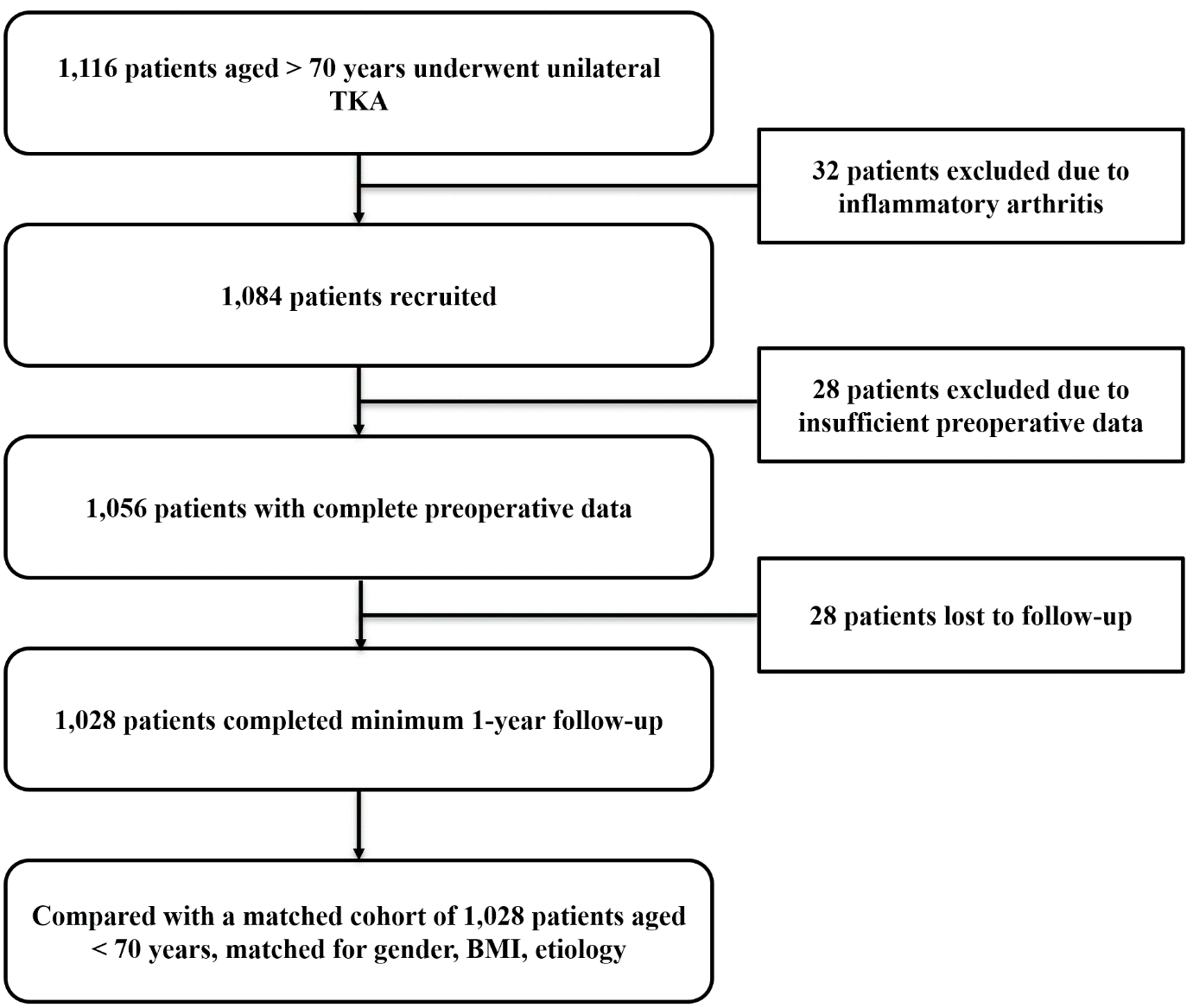

A total of 1116 patients aged over 70 years underwent unilateral TKA between 2016 and 2021. Of these, 32 patients were excluded due to inflammatory arthritis, and 28 were lost to follow-up. An additional 28 patients were excluded due to incomplete pre-operative data. Ultimately, 1028 patients with complete pre-operative information, including age, sex, BMI, comorbidities, and pre-anesthetic evaluation, who completed a 1-year follow-up, were included for final analysis (Fig. 1).

Figure 1: Patient recruitment flowchart.

An equal number of gender- and BMI-matched patients under the age of 70 years formed the comparative cohort.

Patient demographics

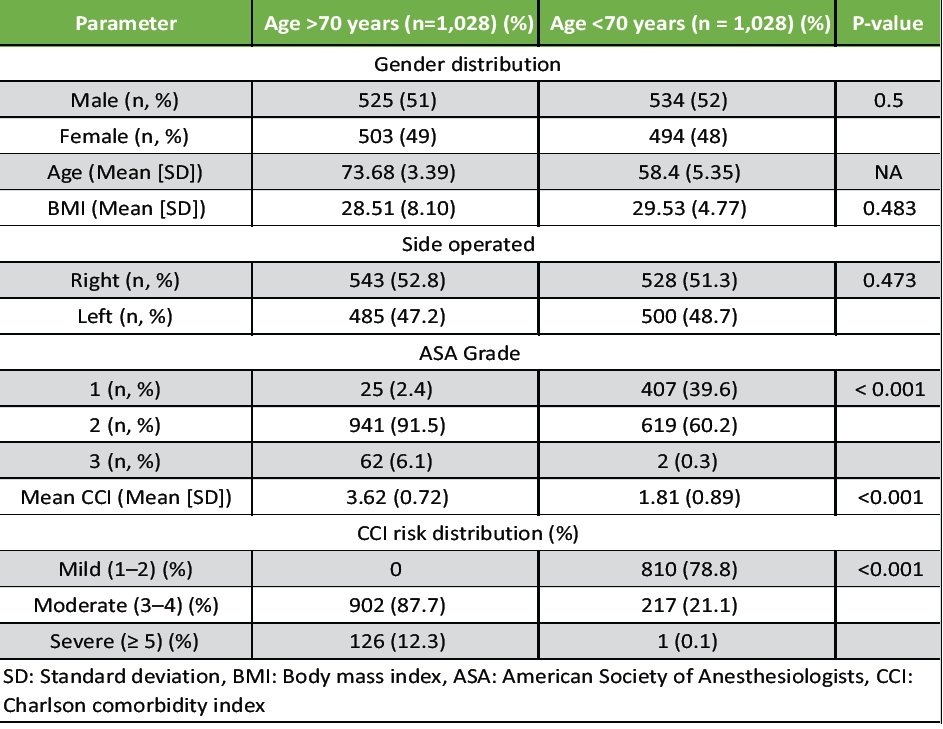

In the under 70 years cohort, the mean age was 58.4 years (SD = 5.35), with an age range from 43 to 69 years; whereas the mean age of the above 70 years cohort was 73.68 years (SD = 3.39), with the age range extending from 71 to 85 years. The demographic characteristics of the patients in both age groups were similar with respect to gender, BMI, and side operated, showing no statistically significant differences. However, significant differences were observed between the groups in terms of ASA grade, mean CCI, and CCI risk class distribution (P < 0.001), reflecting a higher risk profile in older patients, as expected (Table 1).

Table 1: Patient demographics

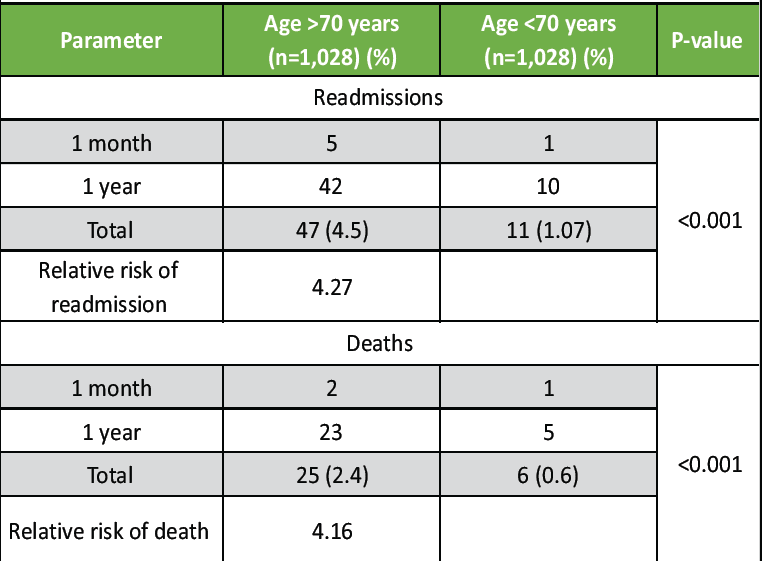

Readmissions and mortality

Readmissions were analyzed at both 1-month and 1-year intervals following TKA. In the cohort aged over 70 years, there were five readmissions within the 1st month and 42 additional readmissions within the 1st year, resulting in a total readmission rate of 4.5%. In contrast, the group aged under 70 years had one readmission in the 1st month and 10 additional readmissions within the 1st year, yielding a total readmission rate of 1.07%. The relative risk of readmission in patients aged over 70 years was calculated to be 4.27.

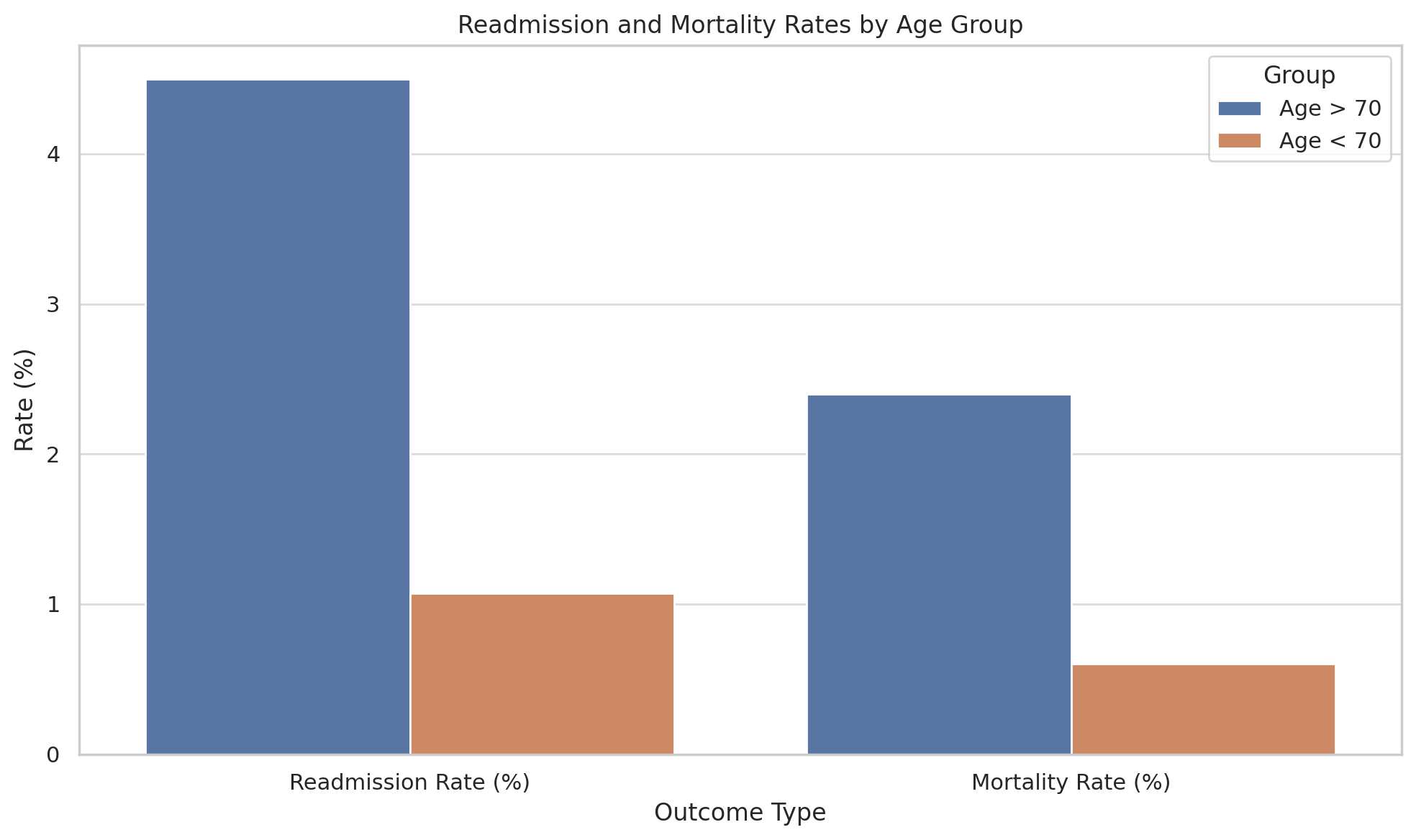

Mortality rates were also higher in the group aged over 70 years, with 25 deaths (2.4% of cases) reported compared to six deaths (0.6% of cases) in the younger group. The relative risk of death in patients aged over 70 years was 4.16 (Table 2 and Fig. 2).

Table 2: Comparison of readmissions and deaths

Figure 2: Patient readmission rate and mortality rate in each cohort.

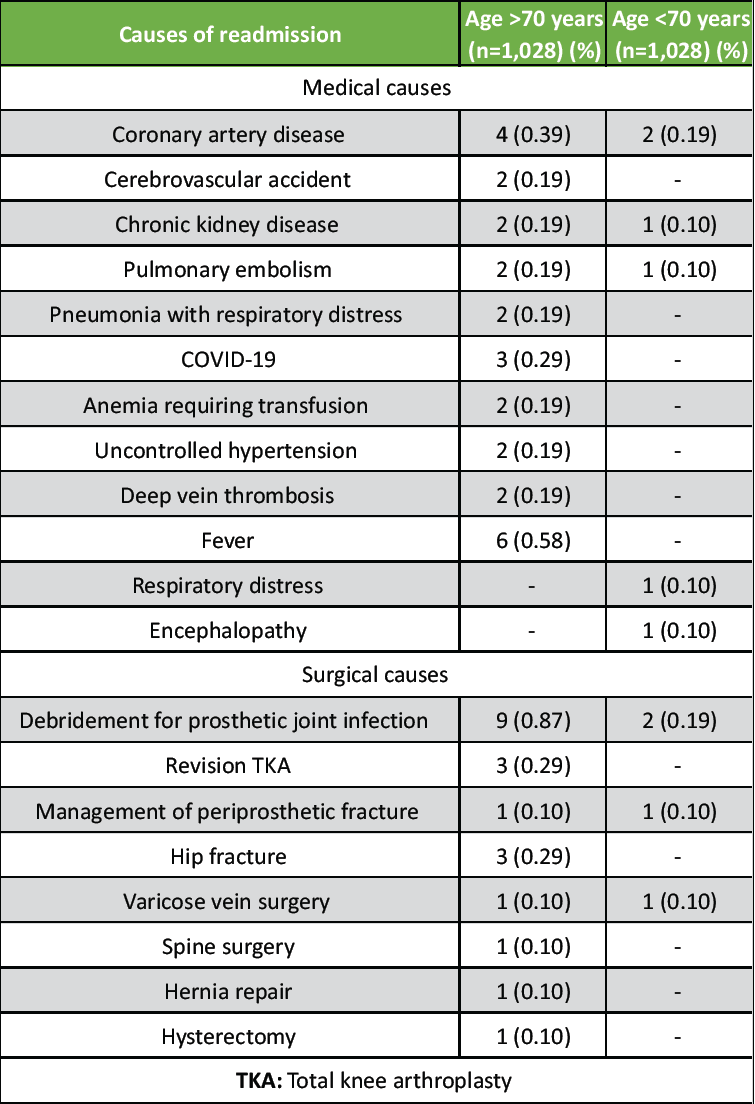

Causes of readmissions and deaths

Readmissions were categorized into medical and surgical causes. In the group aged over 70 years, early readmissions (within the 1st month) were primarily due to medical issues. Specific medical causes and their respective number and percentage include: Coronary artery disease (CAD) (4, 14.8%), cerebrovascular accident (CVA) (2, 7.4%), chronic kidney disease (CKD) (2, 7.4%), pulmonary embolism (2, 7.4%), pneumonia with respiratory distress (2, 7.4%), COVID-19 (3, 11.1%), anemia requiring transfusion (2, 7.4%), uncontrolled hypertension (2, 7.4%), DVT (2, 7.4%), and fever (6, 22.2%). Later readmissions (between 1 month and 1 year) were attributed to CAD, CVAs, CKD, pneumonia with acute respiratory distress syndrome, COVID-19, DVT, uncontrolled hypertension, and fever (Table 3).

Table 3: Etiology for readmissions in both cohorts

Surgical causes of readmission in the group aged over 70 years included: Debridement for prosthetic joint infection (PJI) (9, 45.0%), revision TKA (3, 15.0%), management of periprosthetic fracture (1, 5.0%), hip fracture (3, 15.0%), varicose vein surgery (1, 5.0%), spine surgery (1, 5.0%), hernia repair (1, 5.0%), and hysterectomy (1, 5.0%).

In the group aged under 70 years, early readmissions were mainly due to pulmonary embolism (1, 25.0%). Other medical causes for readmissions between 1 month and 1 year included CAD (2, 28.6%), respiratory distress (1, 14.3%), encephalopathy (1, 14.3%), and CKD (1, 14.3%). Surgical causes in this group included: Debridement for PJI (2, 50.0%), management of periprosthetic fracture (1, 25.0%), and varicose vein surgery (1, 25.0%) (Table 3).

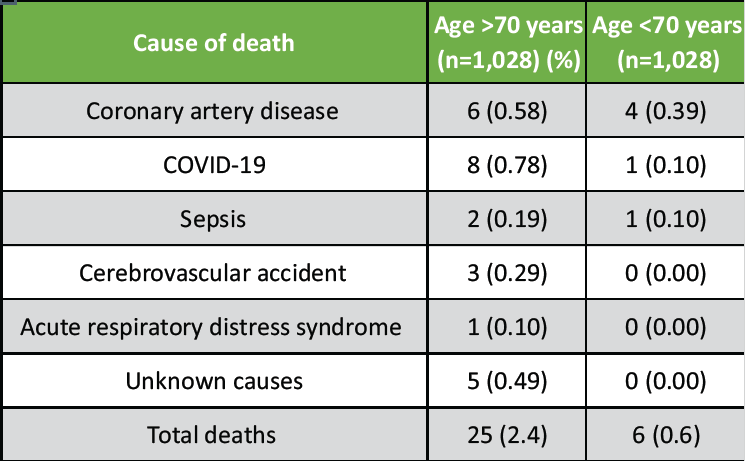

The causes of death were also analyzed. In the group aged over 70 years, deaths within 1 month were primarily due to CAD (6, 24.0%) and respiratory distress (1, 4.0%). Deaths occurring between 1 month and 1 year were attributed to CAD (6, 24.0%), COVID-19 (8, 32.0%), sepsis (2, 8.0%), CVA (3, 12.0%), and unknown causes (5, 20.0%). In the group aged under 70 years, deaths were due to myocardial infarction and CAD (4, 66.7%), COVID-19 (1, 16.7%), and sepsis (1, 16.7%) (Table 4).

Table 4: Etiology for deaths in both cohorts

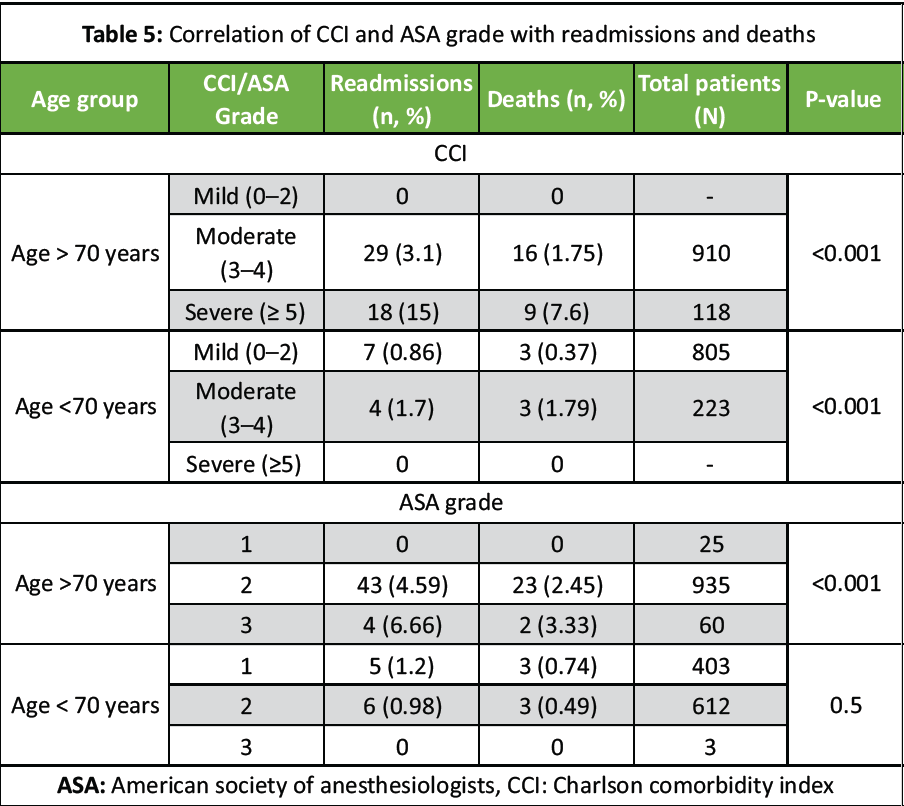

Correlation of CCI and ASA with readmissions and deaths

Correlation analyses were conducted to evaluate the association between the CCI and both readmission and mortality rates. Patients with higher CCI scores demonstrated a significantly increased risk of both readmission and mortality in both age groups (P < 0.001). In addition, higher ASA grades were significantly associated with increased readmissions and mortality rates in patients aged over 70 years (P = 0.001), whereas no significant correlation was observed in the younger group (Table 5).

Table 5: Correlation of CCI and ASA grade with readmissions and deaths

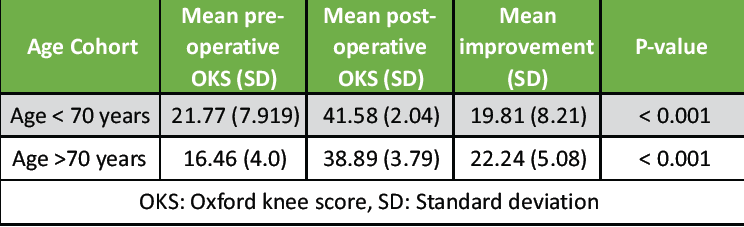

Functional outcomes

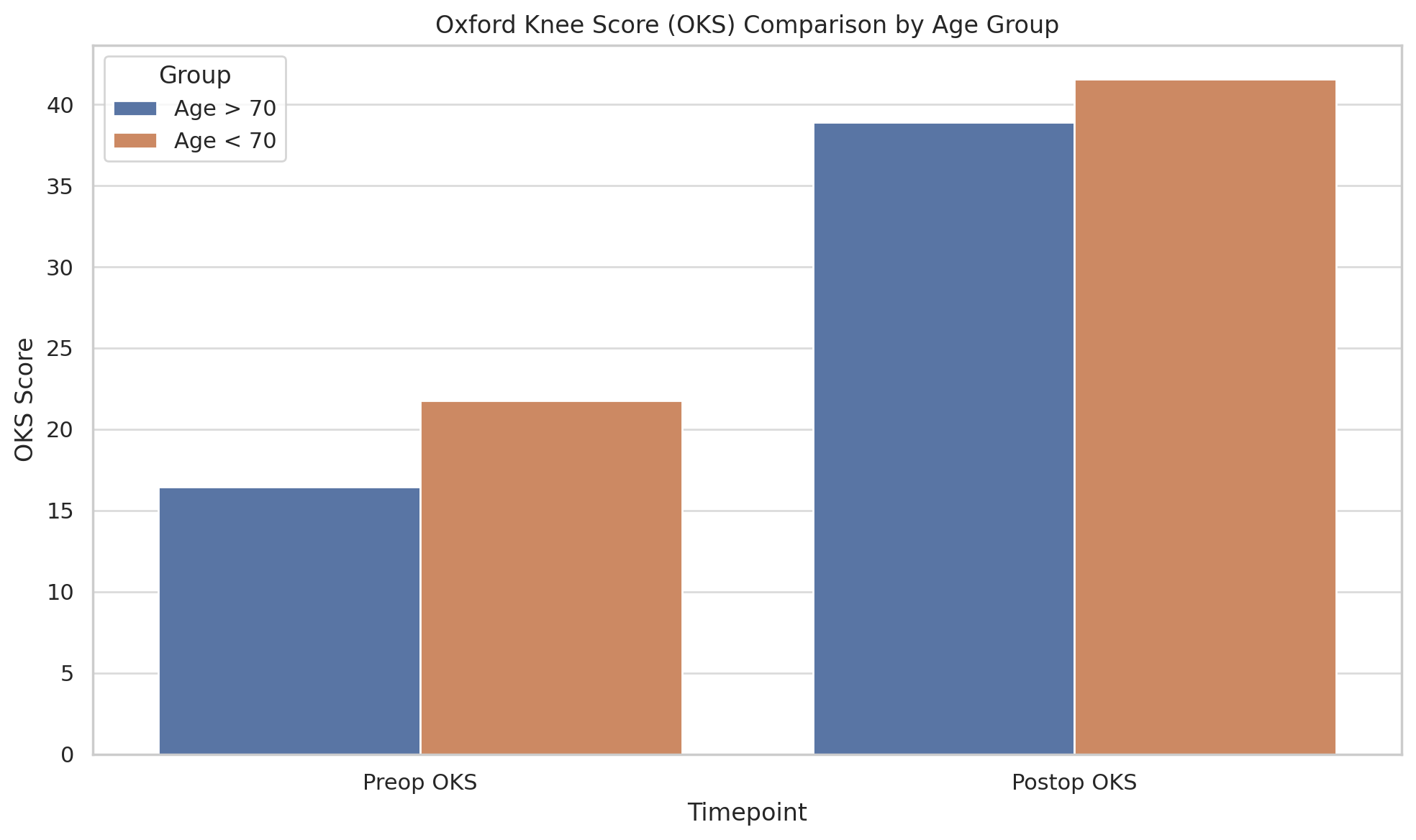

Functional outcomes were assessed using the OKS at the 1-year follow-up. Both age groups exhibited significant improvement in mean OKS scores, indicating substantial functional recovery following TKA (P < 0.001). The mean improvement in the OKS score was significantly greater in the elderly cohort (22.24 points vs. 19.81 points in the younger group); however, this difference was not considered clinically relevant, as it did not exceed the MCID of 5 points (Table 6 and Fig. 3).

Table 6: Functional outcome of patients using the Oxford Knee score

Figure 3: Patient functional outcomes based on the Oxford knee score between both cohorts.

This study provides a comprehensive analysis of the outcomes of TKA in elderly patients, specifically focusing on those aged 70 years or older. Our study observed a readmission rate of 4.5% within the 1st year for patients aged 70 years and above, compared to a rate of 1.07% in younger patients, exhibiting a relative risk of 4.27 for readmission in the over-70 age group. This result aligns closely with the findings of Yohe et al., who reported a readmission rate of 4.7% for elderly patients within the 1st 30 days post-TKA [12]. However, our study’s longer follow-up period of 1 year might explain the similarity in readmission rates, as longer follow-up allows for a more comprehensive assessment of complications and readmissions.

The mortality rate in our elderly cohort was 2.4%, significantly higher than the 0.6% observed in the younger group, which was similarly reported in other studies [14,15,16,17]. This mortality rate exceeds that reported by Cheung et al., who found a mortality rate of 0.7% within 3 months of surgery in patients aged 80 years or older [18]. This discrepancy may be due to differences in follow-up durations and baseline patient comorbidities. Our study also reported a higher mortality rate compared to the systematic review by Woodland et al., which showed low mortality across their systematic review of 18 studies involving older patients above the age of 65 years [11]. The higher mortality observed in our study may be due to the increased burden of comorbidities in the Asian subcontinent, as indicated by higher CCI scores in our elderly cohort.

With respect to functional outcomes, our study showed significant improvements in OKS, with a mean improvement of 22.2 points in the elderly cohort and 19.8 points in the younger group at the 1-year follow-up. However, the difference between the two groups did not reach the MCID of 5 points, suggesting that the improvements in functional outcomes were not clinically superior between age groups. This was similarly reported in other studies where higher OKS scores were found in the elderly cohort compared to younger patients undergoing TKA at 12 months follow-up [17,19,20,21]. Similarly, significant improvement in the Knee Society score from 48 to 92 at 12 months after TKR was reported, with greater improvement in the octogenarian group compared to the non-octogenarian group [22]. Kennedy et al. [15] also reported significant improvement using the Knee Society Function score at 3 years, but showed no significant improvement at 5 and 10 years following TKA in elderly patients, whereas others showed significant improvement even at 5 years and 10 years following TKA using cementless implants [23,24]. This also aligns with Woodland et al., who found that significant improvements in functional outcomes were evident from 6 months to 10 years after TKA in elderly patients [11]. However, other studies have also shown poorer functional outcomes in elderly patients compared to younger patients undergoing TKA, with the elderly cohort being identified as a risk factor for poor functional outcomes after TKA [25,26].

McCalden et al. analyzed implant survivorship in different age groups and found that the revision rate was higher in the younger population (under 70 years) compared to patients over 70 years at both 5 and 10 years follow-ups. They concluded that while the younger population had better clinical and functional outcomes, they also had a higher revision rate compared to the elderly population [25].

Some studies have analyzed the length of stay (LOS) following TKA and found the LOS to be longer in elderly patients over 80 years compared to younger patients [18]. The prolonged LOS in elderly patients may be attributed to increased levels of comorbidities and the greater need for post-operative rehabilitation support. In addition, the adoption of fast-track rehabilitation protocols was associated with shorter LOS and improved functional outcomes in elderly patients, suggesting that such approaches could potentially mitigate the longer LOS [18,27].

The pre-operative condition of the patient, including physical function, mental health, and comorbidities, is crucial in determining the outcomes of TKA [28,29,30]. This is especially important in elderly patients, who exhibit higher morbidity and mortality rates compared to younger individuals undergoing TKA [10]. In addition, the reduced life expectancy in older patients lowers the likelihood of requiring revision surgery due to prosthesis wear, making prosthesis longevity a less significant concern in surgical decision-making for this demographic.

A gradual decline in function with advancing age is likely due to a more sedentary lifestyle and an increased comorbidity burden, rather than being a direct effect of TKA. These findings highlight the importance of continued rehabilitation to maintain and optimize long-term outcomes [15]. The uncertainty regarding long-term results and the potential for functional decline should be addressed in future studies for a more comprehensive understanding of these trends.

Strengths and limitations

The strengths of our study include the use of a large, well-matched cohort that allows for direct comparison between elderly and younger patients, adding valuable evidence to the literature on the outcomes of TKA in elderly patients. The findings support the use of TKA for elderly patients, given the substantial improvements in functional outcomes despite increased risks. However, the study’s retrospective design introduces potential selection bias, and the follow-up duration of 1 year limits the ability to evaluate long-term outcomes. In addition, variability in reporting methods presents challenges in comparing outcomes across different studies. Future prospective studies with standardized outcome measures and longer follow-up durations are warranted to validate these findings and optimize decision-making for elderly patients undergoing TKA.

The results of this study support the use of TKA in patients aged 70 years or older, demonstrating significant improvements in functional outcomes and quality of life. However, the higher rates of readmission and mortality observed in this population necessitate a thorough pre-operative assessment and optimization of comorbidities to mitigate risks. Registry-based data with a large sample size and longer follow-up periods are essential to better understand the long-term outcomes and refine patient selection criteria for TKA in elderly patients.

Elderly patients undergoing TKA can achieve excellent functional outcomes similar to younger individuals, but face a notably higher incidence of post-operative complications, readmissions, and mortality. These risks are significantly influenced by comorbidity burden rather than chronological age. Therefore, a multidisciplinary approach involving thorough pre-operative medical optimization, stratified risk assessment using tools such as the CCI and ASA grade, and individualized rehabilitation planning is essential to improve surgical safety and maximize the benefits of TKA.

References

- 1. Al-Dadah O, Hing C. Factors influencing outcome following total knee arthroplasty. Knee 2024;47:A1-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 2. Dhurve K, Scholes C, El-Tawil S, Shaikh A, Weng LK, Levin K, et al. Multifactorial analysis of dissatisfaction after primary total knee replacement. Knee 2017;24:856-62. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 3. Scott CE, Howie CR, MacDonald D, Biant LC. Predicting dissatisfaction following total knee replacement: A prospective study of 1217 patients. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2010;92:1253-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 4. Kazarian GS, Haddad FS, Donaldson MJ, Wignadasan W, Nunley RM, Barrack RL. Implant malalignment may be a risk factor for poor patient-reported outcomes measures (PROMs) following total knee arthroplasty (TKA). J Arthroplasty 2022;37:S129-33. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 5. Hamilton DF, Burnett R, Patton JT, Howie CR, Moran M, Simpson AH, et al. Implant design influences patient outcome after total knee arthroplasty: A prospective double-blind randomised controlled trial. Bone Joint J 2015;97-B:64-70. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 6. World Health Organization. World Health Statistics 2020: Monitoring Health for the SDGs, Sustainable Development Goals. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2021. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 7. Yan CH, Chiu KY, Ng FY. Total knee arthroplasty for primary knee osteoarthritis: Changing pattern over the past 10 years. Hong Kong Med J 2011;17:20-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 8. Kurtz S, Ong K, Lau E, Mowat F, Halpern M. Projections of primary and revision hip and knee arthroplasty in the United States from 2005 to 2030. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2007;89:780-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 9. Wu X, Law CK, Yip PS. A projection of future hospitalisation needs in a rapidly ageing society: A Hong Kong experience. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2019;16:473. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 10. Soffin EM, YaDeau JT. Enhanced recovery after surgery for primary hip and knee arthroplasty: A review of the evidence. Br J Anaesth 2016;117:iii62-72. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 11. Woodland N, Takla A, Estee MM, Franks A, Bhurani M, Liew S, et al. Patient-reported outcomes following total knee replacement in patients aged 65 years and over-a systematic review. J Clin Med 2023;12:1613. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 12. Yohe N, Funk A, Ciminero M, Erez O, Saleh A. Complications and readmissions after total knee replacement in octogenarians and nonagenarians. Geriatr Orthop Surg Rehabil 2018 Dec 5;9:2151459318804113. doi: 10.1177/2151459318804113. PMID: 30574408; PMCID: PMC6299313. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

- 13. Kuperman EF, Schweizer M, Joy P, Gu X, Fang MM. The effects of advanced age on primary total knee arthroplasty: A meta-analysis and systematic review. BMC Geriatr 2016;16:41. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 14. Murphy BP, Dowsey MM, Spelman T, Choong PF. The impact of older age on patient outcomes following primary total knee arthroplasty. Bone Joint J 2018;100-B:1463-70. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 15. Kennedy IW, Johnston L, Cochrane L, Boscainos PJ. Total knee arthroplasty in the elderly: Does age affect pain, function or complications? Clin Orthop Relat Res 2013;471:1964-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 16. Easterlin MC, Chang DG, Talamini M, Chang DC. Older age increases short-term surgical complications after primary knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2013;471:2611-20. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 17. Clement ND, MacDonald D, Howie CR, Biant LC. The outcome of primary total hip and knee arthroplasty in patients aged 80 years or more. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2011;93:1265-70. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 18. Cheung A, Fu H, Cheung MH, Chan WK, Chan PK, Yan CH, et al. How well do elderly patients do after total knee arthroplasty in the era of fast-track surgery? Arthroplasty 2020;2:16. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 19. Townsend LA, Roubion RC, Bourgeois DM, Leonardi C, Fox RS, Dasa V, et al. Impact of age on patient-reported outcome measures in total knee arthroplasty. J Knee Surg 2018;31:580-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 20. Sloan FA, Ruiz D Jr., Platt A. Changes in functional status among persons over age sixty-five undergoing total knee arthroplasty. Med Care 2009;47:742-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 21. Williams DP, Price AJ, Beard DJ, Hadfield SG, Arden NK, Murray DW, et al. The effects of age on patient-reported outcome measures in total knee replacements. Bone Joint J 2013;95-B:38-44. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 22. Leung TP, Lee CH, Chang EW, Lee QJ, Wong YC. Clinical outcomes of fast-track total knee arthroplasty for patients aged >80 years. Hong Kong Med J 2022;28:7-15. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 23. Whiteside LA, Viganò R. Young and heavy patients with a cementless TKA do as well as older and lightweight patients. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2007;464:93-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 24. Dixon P, Parish EN, Chan B, Chitnavis J, Cross MJ. Hydroxyapatite-coated, cementless total knee replacement in patients aged 75 years and over. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2004;86:200-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 25. McCalden RW, Robert CE, Howard JL, Naudie DD, McAuley JP, MacDonald SJ. Comparison of outcomes and survivorship between patients of different age groups following TKA. J Arthroplasty 2013;28:83-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 26. Franklin PD, Li W, Ayers DC. The Chitranjan Ranawat Award: Functional outcome after total knee replacement varies with patient attributes. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2008;466:2597-604. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 27. Pitter FT, Jørgensen CC, Lindberg-Larsen M, Kehlet H, Lundbeck Foundation Center for Fast-track Hip and Knee Replacement Collaborative Group. Postoperative morbidity and discharge destinations after fast-track hip and knee arthroplasty in patients older than 85 years. Anesth Analg 2016;122:1807-15. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 28. Ghoshal A, Bhanvadia S, Singh S, Yaeger L, Haroutounian S. Factors associated with persistent postsurgical pain after total knee or hip joint replacement: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Pain Rep 2023;8:e1052. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 29. Lungu E, Vendittoli PA, Desmeules F. Preoperative determinants of patient-reported pain and physical function levels following total knee arthroplasty: A systematic review. Open Orthop J 2016;10:213-31. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 30. Melnic CM, Paschalidis A, Katakam A, Bedair HS, Heng M, MGB Arthroplasty Patient-Reported Outcomes Writing Committee. Patient-reported mental health score influences physical function after primary total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2021;36:1277-83. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]