A thorough evaluation involving a multidisciplinary approach is merited for identifying syndromic associations, and contemplating surgical correction for cleft hand and foot syndrome.

Dr. Rajiv Kaul, Department of Orthopaedics, Base Hospital Delhi Cantonment, New Delhi, India. Email: drrajivkaul@gmail.com

Introduction: Cleft hands and feet constitute a rare, congenital abnormality of limb bud development, manifesting as a cosmetically and, occasionally, a functional debility of the hands or feet. Patients often pursue expert advice regarding the surgical reconstruction of their deformities, which may pose an ethical dilemma to the treating practitioner.

Case report: We present a case series of a family of three with bilateral cleft hands and feet, highlighting the dissimilarities in their phenotypic presentation. The clinical pointers indicate a possible syndromic association of ectrodactyly, ectodermal dysplasia, and clefting syndrome. All patients were evaluated for the possibility of surgical reconstruction of their deformities, and were managed non-operatively in view of their satisfactory functional adaptation.

Conclusion: The present report highlights the clinical features, diagnosis, and role of a multidisciplinary approach in the evaluation of this culturally disconcerting disorder. Surgery should be reserved for severe functional limitation in case of cleft hands and unadaptable cleft feet.

Keywords: Cleft hand, cleft foot, ectrodactyly, congenital malformation, multidisciplinary management.

Cleft hand/foot is an infrequent congenital anomaly, which is characterized by a deficiency of central rays in the hand or foot, from shortening of the central digit to the absence of several rays of the hand/foot. The first report of this anomaly was from South Africa in 1770 [1]. The incidence of typical cleft hands is 1 in 90,000 births, and that of atypical cleft hands is 1 in 150,000 births [2]. Bilateral cleft hands occur in 56% of patients, while unilateral deformity occurs in 44% of cases [2]. Bilateral cleft foot with cleft hands has a reported incidence of 1 in 90,000 births, whereas unilateral cleft foot, not associated with cleft hands, is estimated to occur in 1 in 150,000 births [3]. A cleft hand or foot is usually inherited as an autosomal dominant type with reduced penetrance [4], although there are reports of sporadic, autosomal recessive, and X-related forms [5]. Today, numerous defined syndromes are associated with congenital splitting of the hands/feet, such as: split-hand/split-foot (SHSF) syndrome, ectrodactyly-ectodermal dysplasia-clefting (EEC) syndrome, lacrimo-auriculo-dento-digital syndrome, acro-dermato-ungual-lacrimal-tooth syndrome, coloboma-heart defect-atresia choanae-retarded growth-development genital hypoplasia-ear syndrome, vertebral-anal-cardiac-tracheal-esophageal-renal-limb syndrome, Cornelia de Lange syndrome, Smith–Lemli–Opitz syndrome, Adams–Oliver syndrome, Acro-renal mandibular syndrome, focal dermal hypoplasia (Goltz syndrome), ectrodactyly/mandibulofacial dysostosis (Patterson–Stevenson–Fontaine syndrome), ectodermal dystrophy, ectrodactyly, and macular dystrophy (EEM) syndrome etc. [2,6].

Two young girls, aged 8 and 12, along with their mother, aged 32, presented to a tertiary care center for consultation regarding their prominent, cosmetically abnormal hands and feet since birth. Details of individual cases are shared below:

Case 1

The 8-year-old girl presented with bilateral cleft hands and feet, with complaints of discomfort in wearing shoes (Fig. 1).

Figure 1: (a) 8-year-old girl with bilateral cleft hands; (b) Radiographs of both hands; (c) Function of hands; (d) Bilateral cleft feet; (e) Radiographs of both feet; (f) Bottom view of both feet; (g) Ectodermal dysplasia in the form of peg-shaped incisors.

Figure 1: (a) 8-year-old girl with bilateral cleft hands; (b) Radiographs of both hands; (c) Function of hands; (d) Bilateral cleft feet; (e) Radiographs of both feet; (f) Bottom view of both feet; (g) Ectodermal dysplasia in the form of peg-shaped incisors.

Clinical description

Her hand function was adequate to meet her daily requirements, with good grasp and apposition of fingertips. Cutaneous examination revealed a keloid over the sternum, sparse scalp hair, and no other significant abnormalities. Oral examination showed peg-shaped incisors with no evidence of cleft lip or palate. Radiographs of both hands showed the absence of central metacarpals bilaterally, with fusion of the middle phalanx and duplication of the distal phalanx of the left hand. Radiographs of both feet showed the absence of the central metatarsals, transverse bones in the depth of the cleft (left), and brachydactyly with a deviated great toe (right). Ultrasound (USG) abdomen and pelvis showed no congenital anomaly.

Management

In view of the good hand function, surgical intervention was not contemplated, and she was advised to undergo 6-monthly follow-up to monitor the progression of her right toe deformity.

Case 2

Clinical description

The 12-year-old sister, similarly, had bilateral cleft hands and feet; however, her left hand had an abnormally broad commissure, which prevented “pinching” of the digits, resulting in slight functional impairment (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: (a) 12-year-old girl with bilateral cleft hands; (b) Radiographs of both hands; (c) Function of left hand marginally reduced compared to right; (d) Bilateral cleft feet; (e) Radiographs of both feet; (f) Bottom view of both feet; (g) Ectodermal dysplasia in the form of sparse eyebrows and scalp hair.

Her right hand, on the contrary, had good prehensile function. She exhibited hypotrichosis over the scalp and eyebrows with no other significant abnormality on cutaneous, oral, or general physical examination. Radiographs of both hands revealed the absence of the central ray bilaterally, with triphalangeal thumbs. Radiographs of both feet showed the absence of the central 3 rays bilaterally. The USG abdomen and pelvis were normal.

Management

The patient and her mother were informed about the pros and cons of surgical reconstruction of the left hand, and the possibility of hand function remaining unchanged following any intervention. A 6-month follow-up to look for worsening hand function was advised.

Case 3

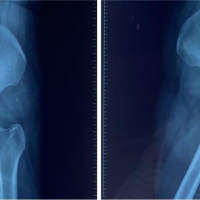

The girls’ mother, likewise, had bilateral, less severe cleft hands and feet, with excellent hand function and shoe-adaptive feet (Fig. 3).

Figure 3: (a) 32-year-old mother of both girls, with bilateral cleft hands; (b) excellent function of both hands; (c) both feet top view; (d) both feet top view; (e) Radiographs of both feet; (f) Cleft palate with hypoplasia of dental enamel; (g) Unilateral cleft lip, sparse eyebrows, and scalp hair; (h) Sparse axillary hair.

Clinical description

Oral examination revealed a unilateral cleft lip and palate on the left side, along with enamel hypoplasia. Her voice had a nasal intonation, indicating velopharyngeal incompetence. Cutaneous examination showed onychodystrophic nail along with sparse axillary and pubic hair, which were vellus in nature. No other congenital anomaly was found on general and systemic examination. Radiographs of both feet showed partial absence of the central 2 rays. USG abdomen and pelvis showed no significant abnormality.

Management

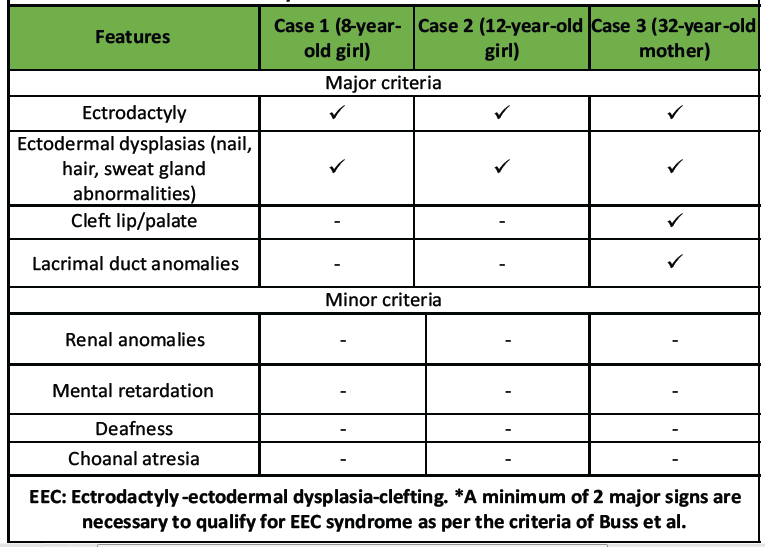

The satisfactory appearance and function of both hands and feet did not warrant any surgical intervention. The clinical findings of cleft lip and palate in the mother, along with ectrodactyly (cleft hands/feet) and ectodermal dysplasia in the form of skin, nail, and hair changes in all individuals, strongly supported the diagnosis of EEC syndrome in the family. A comparison of clinical features of the 3 cases is summarized in Table 1.

Table 1: Comparative clinical features of the 3 patients, supporting the diagnosis of EEC syndrome* in the individuals

Central deficiencies primarily affect the central rays of the hand. Historically, based on the clinical features, they were subdivided into typical and atypical; however, atypical cleft hand became known as symbrachydactyly and was regarded as a transverse rather than a longitudinal deficiency [7]. The hallmark of central hand deficiency is characterized by a V-shaped cleft in the center of the hand, which may or may not be associated with the absence of one or more digits. This is commonly associated with syndactyly, central polydactyly, and skeletal deformity with additional bony bridges between the residual digital rays. The pathogenesis of central deficiency is attributed to a defect in the central portion of the apical ectodermal ridge (AER), and is classified as a malformation of the hand plate in the proximodistal axis, as per the Oberg, Manske, and Tonkin classification [8]. This theory of etiology was derived from animal models, particularly the dactylaplasia mouse that has specific “Dac” gene mutations in two loci on chromosome 19, which expresses a cleft phenotype in its heterozygote form [9]. In this model, the central segment of the AER undergoes apoptosis in the early stages of limb bud development with consequent failure of central digit development. Experimental rats with cleft hand/foot deformity, central polydactyly, and/or osseous syndactyly were produced by Ogino with exposure to the teratogen busulfan [10,11]. It was proposed that disruption of normal FGF8 signaling in the AER and BMP-4 signaling in the underlying mesoderm resulted in combined ectodermal and mesodermal injury that led to failure of normal digital ray induction.

Several classification systems of cleft hand have been described; however, the most useful classification is that of Manske and Halikis, which emphasizes the status of the first web space, which may play a vital role in decision-making regarding surgical reconstruction [12]. This system recognizes the fact that larger clefts may lead to the additional suppression of the index ray, resulting in merger with the first web space, thereby producing a wide and more competent web. More extensive cleft formation, however, can involve the thumb, which can be hypoplastic or even absent. Cleft hand/foot can occur sporadically or as an inherited trait. It is usually inherited as an autosomal dominant trait, though autosomal recessive and X-linked pedigrees have been recognized, mostly with syndromic association, the most common ones being SHSF and EEC syndrome [6,13]. SHSF syndrome is usually inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern with variable penetrance [14]. Seven subtypes with specific gene-mutation loci have been identified on a number of chromosomes [14]. Within each subtype, the phenotype can vary substantially and can have variable penetrance, causing difficulty in predicting future phenotypes in an affected family. The manifestations of cleft hand may vary through a spectrum from mild, with a minor cutaneous cleft in the second web, to severe, with the absence of one or more of the central digits. Syndactyly between the digits adjacent to the cleft is a common occurrence. Duplications are also found bordering the cleft. Within the cleft, transverse tubular bones may be present that further widen the cleft as growth continues. Phalangeal anomalies often coexist with bracketed epiphyses or double phalanges, creating angular deformities within the remaining digits [15]. The metacarpal abnormalities include absence within the cleft, bifid metacarpals, and duplication. The ulnar cleft hand, considered to be a variant of central deficiency, is distinctly different in that the cleft is situated in the fourth web space, and ulnar digits are hypoplastic [16]. Cleft hand is also characterized by predominant wasting of the thenar muscles, with relative sparing of the hypothenar eminence, which can be attributed to dissociated denervation pattern, as seen in SHS associated with Charcot–Marie–tooth disease [17].

In 1970, Rüdiger et al. reported the association of ectrodactyly, atypical anhidrotic ectodermal dysplasia, and cleft lip/palate in a 3½-year-old girl. They coined it “Ectrodactyly Ectodermal Dysplasia and Cleft palate/lip (EEC) syndrome.” This is a rare, autosomal dominant disorder that is inherited with incomplete penetrance and variable expression. The defect develops due to insufficient activity of the median AER, which leads to an increase in apoptosis or a decrease in cell proliferation. The cardinal features include ectrodactyly (cleft hand or foot), cleft lip or palate, and abnormalities of epidermal appendages such as hypotrichosis, hypodontia, dystrophic nails, tear duct, and sweat gland anomalies, as were observed in our patients. Although genetic testing could not be carried out in the present family due to financial limitations, the clinic-radiological features of the mother and her daughters suggest a high probability of EEC syndrome in this family.

Indications for surgery

Flatt aptly described the cleft hand as a “functional triumph but a social disaster” in his 1977 work on congenital hand anomalies [18]. This statement implies that majority of cleft hands, although socially stigmatizing, function well. The perplexing question here is the possibility of diminishing hand function and achieving only marginal esthetic improvement in an otherwise well-functioning extremity. Surgery should aim at improving both cosmesis and function, but never downgrade either. Furthermore, derogatory terms such as “lobster claw” or “pincer” should be avoided at all costs. Broad indications for surgery include: (i) progressive deformity (growth limited by a syndactyly or transverse bony bar), (ii) deficient, non-functional first web space, or (iii) absent thumb. Surgical innervations are challenging to perform and carry a substantial risk of ischemia and flap necrosis. Most surgical interventions are reserved until the child is between 1 and 2 years of age. The Snow-Littler procedure is commonly performed to widen the first webspace by removing the third digit and moving the index finger towards the third metacarpal [19]. This procedure aims to close the cleft and widen the web space between the thumb and index finger. To achieve a more functional alignment, additional soft-tissue releases, transfers, and osteotomies of the metacarpals may be necessary [20]. Any evidence of vascular compromise, such as absent/hypoplastic pectoralis musculature suggesting subclavian artery insufficiency, warrants a staged surgical release [21].

The foot deformities often match the hand deformities [22]. [23] types I and II have only minor abnormalities without absence of the metatarsals, whereas the metatarsals are progressively absent in the remaining types. Type VI is the monodactylous cleft foot with the absence of all rays except the 5th (fibular ray). Cleft foot surgery is indicated if there is difficulty in putting on footwear, secondary to deviation or duplication of digits. This can be achieved by resection of the interposed trapezoidal phalanges, osteotomies of the cuneiforms or metatarsals, and closure of the cleft with appropriate soft-tissue releases [24,25]. However, these procedures must be reserved for individuals with impaired gait or ill-fitting footwear.

The present report highlights the clinical features, diagnosis, and role of a multidisciplinary approach in the evaluation of this culturally disconcerting disorder. Surgery should be reserved for severe functional limitation of the hands and unadaptable cleft feet.

• Cleft hand/foot is a rare congenital deformity that may impair the esthetic appearance, sociability, and self-confidence of a child.

• A thorough evaluation involving a multidisciplinary approach, by a pediatrician, dermatologist, and pediatric orthopedic surgeon, is merited for identifying syndromic associations and contemplating surgical correction

• Early genetic testing and counseling may benefit the affected individuals and their families

• Surgery is indicated in select cases involving diminished hand function or non-shoeable feet, and must be titrated according to the individual’s needs.

References

- 1. Hartsinck G. Beschryving van Guiana of de Wilde Just iin Zuid America. Vol. 2. Amsterdam: Gerrit Teilenburg; 1770. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 2. Baba AN, Bhat YJ, Ahmed SM, Nazir A. Unilateral cleft hand with cleft foot. Int J Health Sci (Qassim) 2009;3:243-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 3. Choudry Q, Kumar R, Turner PG. Congenital cleft foot deformity. Foot Ankle Surg 2010;16:e85-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 4. Elliott AM, Evans JA, Chudley AE. Split hand foot malformation (SHFM). Clin Genet 2005;68:501-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 5. Shamseldin HE, Faden MA, Alashram W, Alkuraya FS. Identification of a novel DLX5 mutation in a family with autosomal recessive split hand and foot malformation. J Med Genet 2012;49:16-20. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 6. Guero S, Holder-Espinasse M. Insights into the pathogenesis and treatment of split/hand foot malformation (cleft hand/foot). J Hand Surg Eur Vol 2019;44:80-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 7. Barsky AJ. Cleft hand: Classification, incidence, and treatment. Review of the literature and report of nineteen cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1964;46:1707-20. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 8. Goldfarb CA, Ezaki M, Wall LB, Lam WL, Oberg KC. The Oberg-Manske-Tonkin (OMT) classification of congenital upper extremities: Update for 2020. J Hand Surg Am 2020;45:542-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 9. Seto ML, Nunes ME, MacArthur CA, Cunningham ML. Pathogenesis of ectrodactyly in the Dactylaplasia mouse: Aberrant cell death of the apical ectodermal ridge. Teratology 1997;56:262-70. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 10. Naruse T, Takahara M, Takagi M, Oberg KC, Ogino T. Busulfan-induced central polydactyly, syndactyly and cleft hand or foot: A common mechanism of disruption leads to divergent phenotypes. Dev Growth Differ 2007;49:533-541. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 11. Ogino T. Teratogenic relationship between polydactyly, syndactyly and cleft hand. J Hand Surg Br 1990;15:201-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 12. Manske PR, Halikis MN. Surgical classification of central deficiency according to the thumb web. J Hand Surg Am 1995;20:687-97. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 13. Gül D, Oktenli C. Evidence for autosomal recessive inheritance of split hand/split foot malformation: A report of nine cases. Clin Dysmorphol 2002;11:183-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 14. Ianakiev P, Kilpatrick MW, Toudjarska I, Basel D, Beighton P, Tsipouras P. Split-hand/split-foot malformation is caused by mutations in the p63 gene on 3q27. Am J Hum Genet 2000;67:59-66. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 15. Cooney W. Camptodacytyly and clinodactyly. In: Carter P, editor. Reconstruction of the Child’s Hand. Philadelphia, PA: Lea & Feibige; 1991. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 16. Falliner AA. Analysis of anatomic variations in cleft hands. J Hand Surg Am 2004;29:994-1001. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 17. Bertini A, Moscatelli M, Ciano C, Verri M, Cavalca E, Sconfienza LM, et al. Split hand syndrome in Charcot-Marie-tooth disease type X1 (CMTX1): A clinical, neurophysiological, and radiological study. Eur J Neurol 2025;32:e70188. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 18. Flatt A. The Care of Congenital Hand Anomalies. St. Louis: Mosby; 1977. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 19. Snow JW, Littler LJ. Surgical Treatment of Cleft Hand. Transactions of the Fourth International Congress of Plastic Surgery. Amsterdam: Surgical Treatment of Cleft Hand; 1967. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 20. Wolfe SW, Pederson WC, Kozin SH, Cohen MS. Green’s Operative Hand Surgery. New York: Elsevier Health Sciences; 2021. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 21. Davis DD, Kane SM. Cleft hand. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing; 2025. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/nbk557807; Last Update: August 8, 2023 [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 22. Sharma S, Chhetri A, Singh A. Congenital cleft foot and hand. Indian Pediatr 1999;36:935-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 23. Blauth W, Borisch NC. Cleft feet. Proposals for a new classification based on roentgenographic morphology. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1990;258:41-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 24. Wood VE, Peppers TA, Shook J. Cleft-foot closure: A simplified technique and review of the literature. J Pediatr Orthop 1997;17:501-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 25. Leonchuk SS, Neretin AS, Blanchard AJ. Cleft foot: A case report and review of literature. World J Orthop 2020;11:129-36. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]