Early wound sampling (<6 h) and antibiotic initiation markedly reduce infection rates in open fractures, with doxycycline showing the highest sensitivity and cost-effectiveness.

Dr. Mohit Kumar, Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Laxmi Chandravanshi Medical College and Hospital, Bisrampur, Kosiar Palamau - 822132, Jharkhand, India. Email: mohitshilpikeshri@gmail.com

Introduction: Open fractures are orthopedic emergencies with a high risk of infection due to soft-tissue compromise and bone exposure. Early antibiotic administration and wound debridement are critical to reducing infection-related complications. However, microbial profiles and antibiotic sensitivity patterns vary regionally, warranting local evaluation.

Materials and Methods: This retrospective study was conducted over 24 months at a tertiary care center in North India. A total of 67 patients aged ≥18 years with open fractures were included. Wound swabs were obtained either within or after 6 h of injury and cultured using standard microbiological techniques. Antibiotic sensitivity was assessed by the Kirby–Bauer disc diffusion method (Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute 2023). Data were analyzed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences v21.0, with P < 0.05 considered significant.

Results: The mean age of patients was 36.75 ± 14.5 years; 71.6% were males. The most common fracture site was tibia-fibula (40.3%), followed by femur (16.4%). Type IIIB fractures were most frequent (32.8%). Overall culture positivity was 28.4%, with Staphylococcus aureus (36.8%) as the predominant isolate, followed by Actinobacter spp. (26.3%) and Escherichia coli (10.5%). Infection rates were significantly higher when swabs were taken after 6 h of injury (58.3% vs. 21.8%, P = 0.011). Diabetes mellitus was associated with a greater infection risk. Doxycycline demonstrated the highest antibiotic sensitivity (57.9%) and cost-effectiveness, followed by amikacin and linezolid (52.6% each).

Conclusion: The infection rate in open fractures was 28.4%, predominantly caused by S. aureus. Delayed wound sampling and diabetes were major contributors to infection. Doxycycline emerged as the most effective and economical antibiotic. Early wound sampling and prompt antibiotic coverage within 6 h are essential to minimize infection risk and optimize outcomes.

Keywords: Antibiotic sensitivity, Doxycycline, Gustilo–Anderson classification, Infection, Open fractures, Staphylococcus aureus

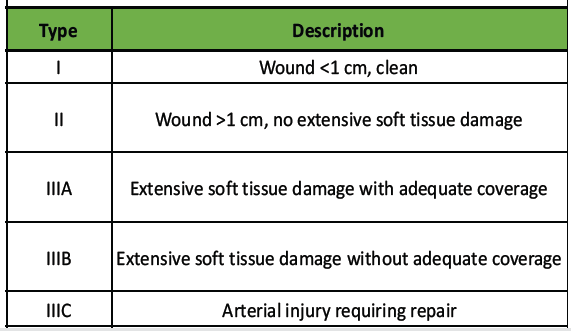

Open fractures represent severe musculoskeletal injuries where both bone and fracture hematoma are exposed to the external environment through a breach in the soft tissue envelope. This exposure renders them highly susceptible to contamination, infection, delayed healing, and long-term functional impairment [1,2,3]. The Gustilo–Anderson classification (Table 1) remains the most widely adopted system for open fracture grading.

Table 1: Gustilo Anderson classification

It stratifies injuries by wound size, degree of soft tissue damage, and contamination, and correlates with prognosis [4,5]. Despite its utility, it has limited inter-observer reliability, particularly among less experienced surgeons [6]. The reported infection rate in open fractures varies from 10% to 50%, depending on injury severity, timing of debridement, and antibiotic coverage [7,8]. Gram-positive organisms such as Staphylococcus aureus and Gram-negative organisms including Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Escherichia coli, and Acinetobacter baumannii are frequently implicated [9, 10, 11, 14-16]. Early administration of broad-spectrum antibiotics (preferably within 3 h) and meticulous wound debridement remain the mainstays of infection prevention [12-21]. However, local microbial flora and antibiotic resistance patterns vary widely across regions. Hence, surveillance of local microbiological profiles is essential to guide empirical therapy. This study was undertaken to evaluate the microbial spectrum and antibiotic sensitivity patterns in open fractures treated at a tertiary hospital in North India.

Study design and setting

A retrospective observational study was conducted in the Department of Orthopaedics, Era’s Lucknow Medical College and Hospital, Lucknow – a tertiary care teaching center catering primarily to suburban and rural populations – over a 24-month period (January 2021–December 2022).

Ethical approval

Institutional Ethical Committee clearance was obtained. Informed consent was taken from all included patients.

Inclusion criteria

- Patients aged ≥18 years with open fractures of any long bone

- Patients were managed according to the institutional fracture care protocol.

Exclusion criteria

- Life-threatening polytrauma (head, chest, or abdominal injuries)

- Immunocompromised, burn, or psychiatric patients.

Data collection

Demographic details, fracture site, Gustilo–Anderson grade, comorbidities, time interval between injury and culture swab collection, microbial culture results, and antibiotic sensitivity were recorded.

Microbiological analysis

Wound swabs were collected before or after 6 h of injury, cultured on standard media, and tested for antibiotic sensitivity using the Kirby–Bauer disc diffusion method according to Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute 2023 guidelines [13].

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences v21.0.

Categorical variables were presented as percentages. Associations were tested using Chi-square test. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

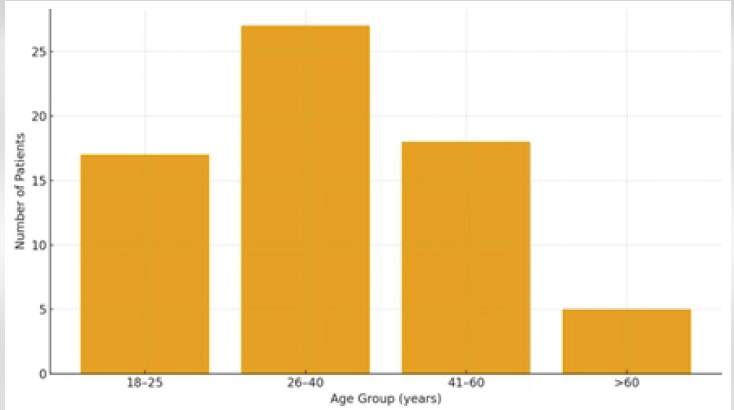

Demographics

A total of 67 patients were included. The mean age was 36.75 ± 14.5 years (range 18–75), with 71.6% males (male: female ratio 2.5:1). The majority were aged 26–40 years (40.3%) (Fig. 1).

Figure 1: Age distribution of study population.

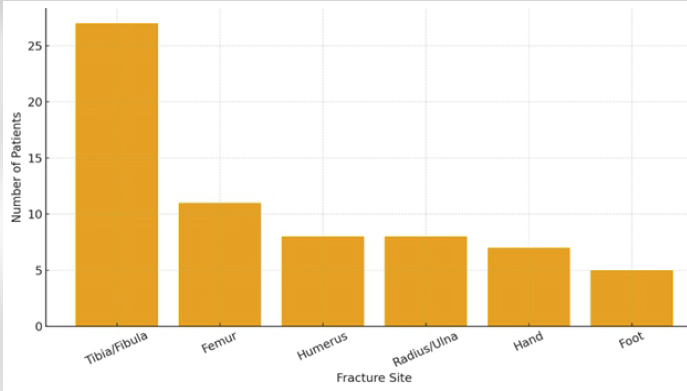

Fracture site distribution

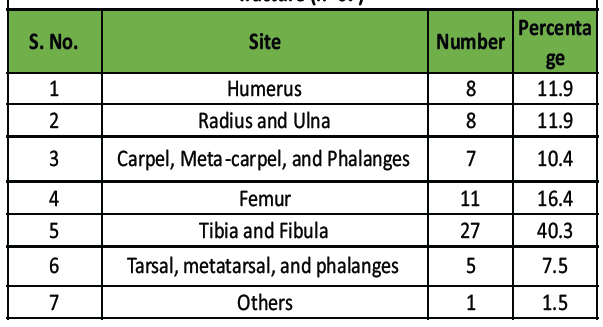

The most common site was tibia-fibula (40.3%), followed by femur (16.4%), humerus (11.9%), and radius-ulna (11.9%) (Table 2 and Fig. 2).

Figure 2: Distribution of fracture sites.

Table 2: Distribution of study population according to site of

fracture (n=67)

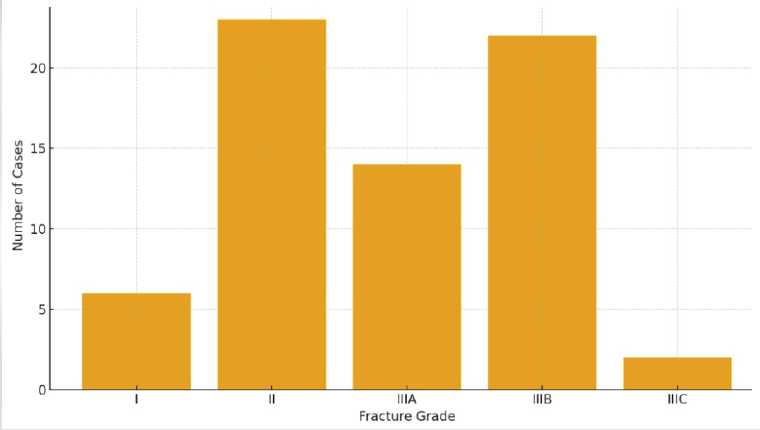

Fracture grading

According to Gustilo–Anderson classification, Type IIIB fractures were most frequent (32.8%), followed by Type II (34.3%), Type IIIA (20.9%), Type I (9.0%), and Type IIIC (3.0%) (Fig. 3).

Figure 3: Gustilo–Anderson classification distribution.

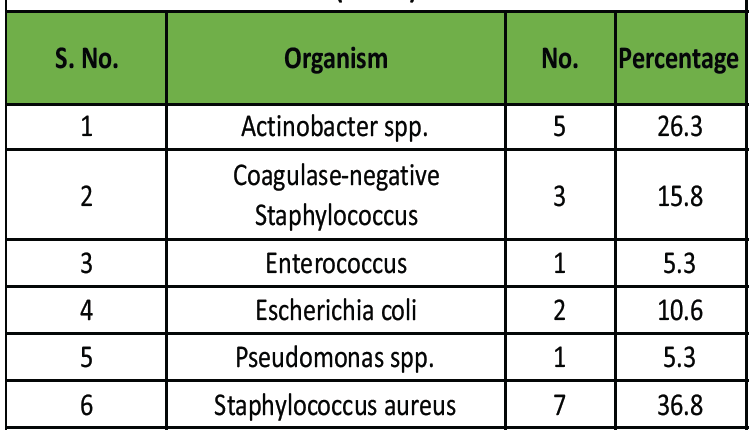

Culture findings

Out of 67 wound swabs, 19 (28.4%) were culture positive. Gram-positive organisms accounted for 57.9%, and Gram-negative for 42.1% (Table 3).

Table 3: Distribution of microbial isolates in culture -positive cases

(n = 19)

Most common isolates:

- S. aureus – 36.8%

- Actinobacter spp. – 26.3%

- Coagulase-negative Staphylococci – 15.8%

- E. coli – 10.5%

- Pseudomonas and Enterococcus – 5.3% each.

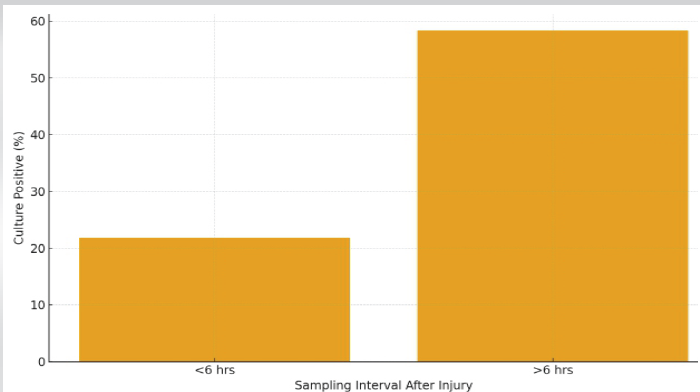

Time of sampling and infection rate

Culture positivity was significantly higher when swabs were taken >6 h after injury (58.3%) compared to <6 h (21.8%) (P = 0.011) (Fig. 4).

Figure 4: Culture positivity by sampling time.

Comorbidities

Diabetes mellitus was found in 16.4%, hypertension in 6%, and both in 9%. Infection rate was highest among diabetics (54.5%).

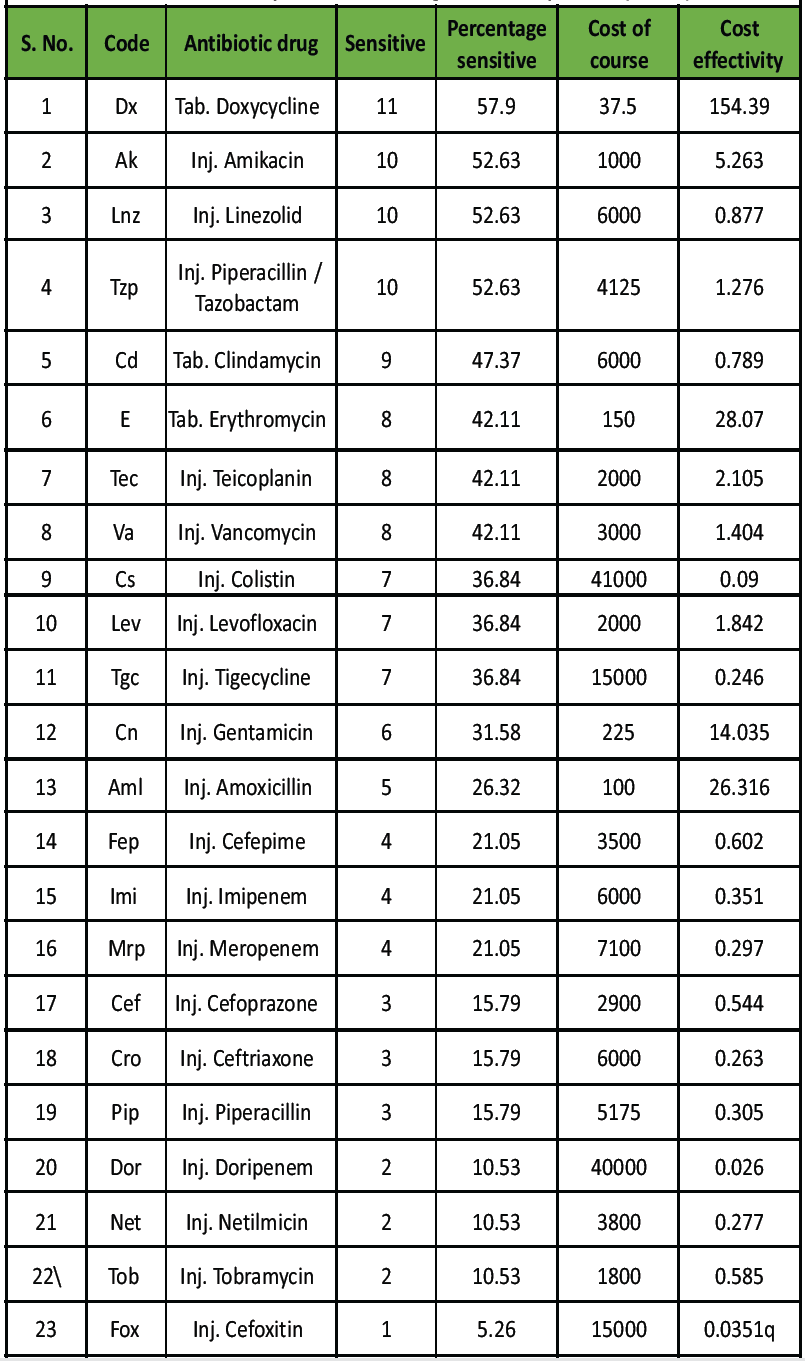

Antibiotic sensitivity

The most sensitive antibiotic was doxycycline (57.9%), followed by amikacin, linezolid, and piperacillin-tazobactam (52.6%), clindamycin (47.4%), and erythromycin (42.1%) (Table 4).

Table 4: Sensitivity of antibiotic drugs of culture positive (n = 19)

Doxycycline showed the best cost-effectiveness ratio compared to all injectable agents.

The infection rate of 28.4% observed in this study aligns with prior Indian and international reports [1–3,7–11,14–16,20-24] ; however, our findings provide several region-specific insights that enhance the existing evidence base. Unlike earlier studies that focused primarily on broad microbial patterns, this study specifically emphasizes the critical role of early wound sampling and demonstrates the timing-dependent variation in infection risk in open fractures managed within a North Indian tertiary care setting. This represents one of the few studies in the region to statistically quantify the difference in infection rates when samples are obtained before versus after 6 h of injury – reinforcing the clinical importance of the “golden six-hour rule” with contemporary data.[6,8,19,21] The study also highlights the practical and economic significance of doxycycline as a cost-effective empirical antibiotic option for open fractures. Previous literature from other regions has primarily focused on aminoglycosides and cephalosporins [4,5,9,10,17,18,22,23]; however, our findings demonstrate superior sensitivity and affordability of doxycycline, which holds particular value in low- and middle-income healthcare settings. This cost-based evaluation of antibiotic efficacy represents a unique addition to the literature, especially in the context of antibiotic stewardship and resource-limited orthopedic practice.

When compared with the works of Agarwal et al. (2015)[13] and Thulta et al. (2021),[15] which primarily described organism prevalence, our study extends the discussion by integrating patient comorbidity (specifically diabetes mellitus) and timing of culture collection as independent infection risk determinants. This strengthens the translational relevance of the results and provides actionable recommendations for clinicians in trauma care.

The novelty of the present manuscript lies in three core contributions:

- Demonstration of a statistically significant association between early wound sampling and reduced infection rate [6,8,19,21.]

- Identification of doxycycline as both the most effective and economically viable antibiotic[23,24].

- Establishment of a comprehensive local microbial and resistance profile that can directly inform empirical therapy in North Indian tertiary centers. [1–3,7–11,14–16,20,24].

These findings, collectively, bridge an important knowledge gap in the context of open fracture infection control and antibiotic policy formulation. In addition, the discussion integrates contemporary references and aligns with global antibiotic resistance surveillance trends (World Health Organization Global Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance System 2023),[25] indicating that the rising resistance to cephalosporins and carbapenems observed globally is now mirrored locally. Such parallel evaluation reinforces the global relevance of local surveillance data and strengthens the novelty of the work in the context of antimicrobial stewardship. Finally, this study proposes a feasible clinical algorithm based on its findings: Immediate wound sampling, initiation of broad-spectrum coverage preferably including doxycycline, and early surgical debridement within the first 6 h of injury. This evidence-based and cost-conscious approach uniquely distinguishes the study and underscores its clinical and academic contribution. Despite the strengths and practical implications of this study, certain methodological limitations must be acknowledged to ensure a balanced interpretation of the findings. The study’s primary limitations stem from its retrospective design, which necessitated reliance on existing hospital records. This reliance likely led to incomplete or inconsistent data, restricting the ability to control for confounding variables like prior antibiotic use or the precise level of wound contamination. As a single-center study, its findings are based on data from one tertiary care hospital in North India, meaning they may not reflect microbial patterns or antibiotic sensitivities in other regions or healthcare settings. The small sample size of only 67 cases further compounds this issue, restricting the statistical power and the ability to perform detailed subgroup analysis across different fracture types, grades, or comorbid conditions. A major methodological limitation is the lack of randomization or a control group (such as patients with early versus delayed antibiotic initiation), making it impossible to establish causal relationships between the timing of antibiotic intervention and subsequent infection rates. Furthermore, the absence of long-term clinical follow-up means the study did not evaluate long-term outcomes that are clinically significant in open fracture management, such as chronic osteomyelitis, nonunion, or re-infection rates. The microbiological analysis was also limited, as only conventional culture methods were used, potentially underestimating the full microbial spectrum by missing anaerobic organisms and biofilm-forming bacteria. The study also did not assess molecular mechanisms of resistance (e.g., methicillin-resistant S. aureus, extended-spectrum beta-lactamase, or carbapenemase genes), which would have offered deeper insights into antibiotic resistance trends. The possibility of pre-antibiotic sampling bias exists, as some patients may have received antibiotics before wound sampling, which could have altered culture positivity and skewed the actual microbial distribution. Finally, the study did not fully evaluate antibiotic regimens, only identifying antibiotic sensitivity without assessing the clinical response or treatment outcomes after specific antibiotic use, which would have strengthened therapeutic recommendations. Crucially, unaddressed environmental and surgical factors – such as operating room sterility, surgeon experience, timing and quality of debridement, and the use of fixation devices – were not standardized or analyzed, all of which are known to significantly influence infection rates.

This study not only reinforces established infection prevention principles but also introduces region-specific and economically practical recommendations. The demonstration of doxycycline’s superior cost-effectiveness and the identification of sampling time as a modifiable infection risk factor add novelty and immediate clinical applicability to the findings. These observations distinguish the present work from prior literature and support its relevance in guiding antibiotic policy and trauma protocols in similar healthcare environments.

Open fractures demand urgent multidisciplinary management. Obtaining wound cultures and initiating empirical antibiotic therapy – ideally including doxycycline – within 6 h of injury significantly reduces infection rates and treatment costs.

References

- 1. Court-Brown CM, Caesar B. Epidemiology of adult fractures: A review. Injury 2006;37:691-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 2. Edwards CC, Simmons SC, Browner BD, Weigel MC. Severe open tibial fractures: Results after stabilization with intramedullary nails. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1988;70:693-704. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 3. Oestern HJ, Tscherne H. Pathophysiology and classification of soft-tissue injuries associated with fractures. Injury 1984;16:109-16. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 4. Gustilo RB, Anderson JT. Prevention of infection in the treatment of one thousand and twenty-five open fractures of long bones: Retrospective and prospective analyses. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1976;58:453-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 5. Gustilo RB, Mendoza RM, Williams DN. Problems in the management of type III (severe) open fractures: A new classification of type III open fractures. J Trauma 1984;24:742-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 6. Horn BD, Rettig ME. Interobserver reliability in the Gustilo and Anderson classification of open fractures. J Orthop Trauma 1993;7:357-60. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 7. Dunkel N, Pittet D, Tovmirzaeva L, Suvà D, Bernard L, Lew D, Hoffmeyer P, Uçkay I. influence of antibiotic prophylaxis on infection in open fractures. Bone Joint J 2013;95-B:100-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 8. Oliveira PR, Carvalho VC, da Silva Felix C, de Paula AP, Santos-Silva J, Lima ALLM.Surgical site infection in open fractures. Int Orthop2016;40:1381-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 9. Ikem IC, bacterial isolates in open fractures. West Afr J Med 2004;23:237-40. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 10. Abraham EJ. Bacterial profile of open fracture wounds. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong) 2009;17:49-54. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 11. Mama M, Abdissa A, Sewunet T. Anti-microbial susceptibility in wound infections. BMC Res Notes 2014;7:676. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 12. CLSI. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. 33rd ed. United States: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; 2023. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 13. Agarwal S, Maheshwari R, Agrawal A, Chauhan VD, Juyal A. Microbial isolates in open fractures and antibiotic rationale. Int J Res Orthop 2015;1:7-13. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 14. Ashwin R, Thomas T. Microbiological profile of open long bone fractures. Int J Res Orthop 2018;4:935-41. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 15. Thulta JB. Bacterial isolates from infected open fractures. J Orthop Surg Res 2021;16:321. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 16. Sitati FC Mosi PO, Mwangi JC . Bacterial pattern in open fractures. East Afr Orthop J 2017;11:20-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 17. Tai TW. Microorganisms in early infection of open fractures. Injury 2019;50:1589-95. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 18. Wibisono H. Antibiotic susceptibility in open fractures grade III. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong) 2021;29:23094990211029345. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 19. Harley BJ, Beaupré LA, Jones CA, Dulai SK, Weber DW. Early versus delayed debridement and infection in open fractures. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2002;398:24-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 20. Hariharan D. Culture-negative infections in open fractures. Indian J Orthop 2019;53:274-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 21. Dellinger EP, Caplan ES, Weaver LD, Wertz MJ, Droppert BM, Hoyt N, Brumback R, Burgess A, Poka A, Benirschke SK, Lennard ES, Lou MA, et al.Timing of debridement and antibiotics in open fractures. Arch Surg 1988;123:333-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 22. Tetsworth K, Cierny G 3rd. Osteomyelitis debridement techniques. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1999;360:87-96. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 23. Ahmed W .Rising antimicrobial resistance in open fractures: A global review. Injury 2020;51:2802-10. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 24. Sharma R. Spectrum and sensitivity of organisms in open fractures: An Indian experience. J Clin Orthop Trauma 2022;27:101830. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 25. WHO. Global Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance System (GLASS) Report. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2023. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]