PFN offers good load-sharing fixation with less stress risers and spans the entire femur, correcting deformities and preventing future fractures.

Dr. Shangreicham Hongvah, Department of Orthopedics, Government Medical College, Aurangabad, Maharashtra, India. E-mail: atohongvah@gmail.com

Introduction: Osteogenesis imperfecta (OI) is a rare inherited connective tissue disorder caused by defective type I collagen, which predisposes patients to recurrent fractures, skeletal deformities, and long-term disability. Intramedullary nailing is widely regarded as the gold standard for surgical stabilization of long bone fractures in OI due to its load-sharing capacity, deformity correction, and ability to prevent future fractures.

Case Report: We describe the case of a 34-year-old female with type IA OI who presented with a spontaneous mid-shaft femur fracture while weight-bearing. She had a history of multiple previous fractures, including bilateral forearm fractures and an atypical femoral fracture, all managed conservatively.

Intervention: The patient underwent closed reduction and internal fixation with a proximal femoral nail (PFN). Under fluoroscopic guidance, a long intramedullary nail was inserted, and proximal and distal locking screws were applied to ensure stability. The procedure was performed with minimal soft-tissue disruption.

Outcome: Radiographic follow-up demonstrated progressive fracture consolidation at 8 weeks, allowing transition to full weight-bearing by 5 months. The patient regained near pre-injury functional status without complications such as implant migration, delayed union, or infection.

Conclusion: This case highlights the effectiveness of PFN in managing femoral fractures in OI patients. PFN provides stable fixation, facilitates early mobilization, and reduces refracture risk. With careful implant selection, surgical planning, and vigilant post-operative monitoring, intramedullary nailing significantly improves functional outcomes and quality of life in OI patients.

Keywords: Osteogenesis imperfecta, femur fracture, proximal femoral nail, intramedullary nailing, load-sharing fixation.

Osteogenesis imperfecta (OI) is a rare, inherited connective tissue disorder marked by insufficient or defective type I collagen, leading to recurrent fractures, bone deformities, and chronic disability in affected individuals. Management of OI requires a multidisciplinary approach that includes medical management, physical rehabilitation, and surgical intervention for fracture stabilization and deformity correction. Among various surgical strategies, intramedullary nailing has become the gold standard for the management of long-bone fractures and deformities in OI [1,2]. Intramedullary nailing significantly reduces the risk of refractures, facilitates early mobilization, and promotes functional independence [3]. Success depends on careful implant selection, individualized surgical technique, and vigilant post-operative monitoring for complications such as infection, implant migration, or delayed union [4]. Proximal femoral nailing offers: Load-sharing fixation, essential in osteoporotic bone to avoid stress risers and implant failure [5]. The ability to span the entire femur, correcting existing deformity and preventing future fractures, and a minimally invasive technique, with reduced periosteal disruption and preservation of soft-tissue attachments.

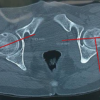

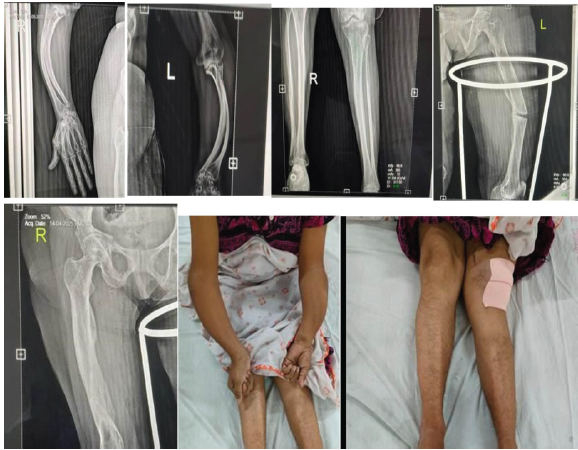

A 34-year-old female with known type ⅠA OI was admitted to our emergency department for a spontaneous left midshaft femur fracture on weight-bearing. She had a history of an atypical left femur fracture 1 month back, for which she was managed conservatively on oral medications. She also reported that she had a right femur fracture at 18 months of age while massaging, then had B/L upper limb forearm fractures while playing at around 8–10 years, all managed conservatively. The patient is of short stature with 1.30 m (Figs. 1 and 2).

Figure 1: X-rays of right atypical right femur fracture, which was managed conservatively.

Figure 2: Pre-operative X-rays and clinical photos of the upper limb and lower limbs.

On presentation, the patient was conscious, oriented, and hemodynamically stable, with complaints of pain and swelling in her left femur. The diagnostic workup revealed a midshaft left femur fracture with bowing deformity. Bony deformities are present in almost every long bone.

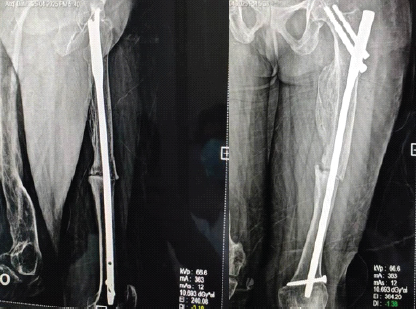

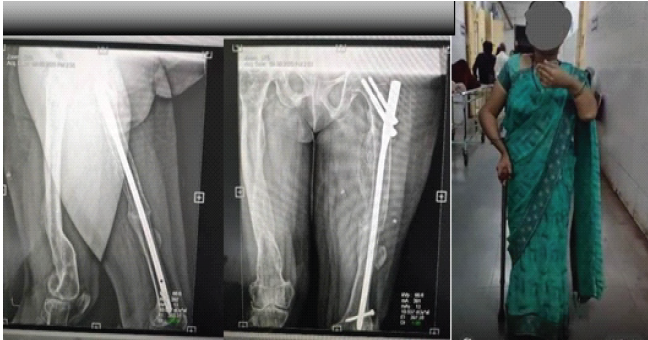

Patient pre-anesthetic evaluation workup was done and posted for surgery. The patient was placed supine on a fracture table, after standard painting and draping, and slight traction was applied. Moreover, closed reduction of the fracture was attempted and achieved under C-arm guidance. A small lateral incision was made proximal to the greater trochanter. An entry point was made at the tip of the greater trochanter under image guidance, and a guidewire was passed through the proximal femur into the shaft. Reaming was done over the guidewire sequentially. A long proximal femoral nail (PFN) (length: 28 cm, diameter: 9 mm) was inserted over the guidewire. Fracture alignment was confirmed under C-arm. 8 mm and 6 mm proximal locking screws were inserted through the jig. Distal locking was done using the freehand technique under C-Arm. Final fluoroscopy confirmed satisfactory fracture reduction, implant position, and screw placement. The wound was irrigated with saline, and hemostasis was ensured. Wound closure was done in layers. A sterile dressing was applied. The post-operative patient was allowed toe-touch with a Zimmer walking frame. Clinical and radiographic follow-up showed no displacement and consolidation after 8 weeks, and hence, full weight-bearing was started as tolerated. The patient was followed up after 5 months, and her physical status was almost comparable to the pre-operative level without any complications (Fig. 3, 4, 5, 6).

Figure 3: Immediate post-operative X-rays.

Figure 4: Partial-weight bearing X-rays after 2 weeks.

Figure 5: Partial weight-bearing X-ray after 3 months.

Figure 6: Full weight bearing after 5 months.

The management of fractures in patients with OI remains a major orthopedic challenge due to the inherent bone fragility, deformities, and altered biomechanics associated with defective type I collagen [7,8,9]. Intramedullary nailing has been widely accepted as the gold standard for long-bone stabilization in OI, as it provides stable load-sharing fixation, spans the entire bone to minimize stress risers, and allows correction of pre-existing deformities [4]. These advantages make it superior to plate fixation, which is associated with a higher incidence of refractures at the ends of the plate, and to conservative management, which may predispose patients to prolonged immobilization, malunion, and further fragility-related injuries. In the present case, a long PFN was selected because of its biomechanical superiority in achieving axial, rotational, and bending stability in osteoporotic bone while maintaining minimal soft-tissue disruption [6,5].

The successful outcome in our patient reinforces evidence from previous literature supporting intramedullary fixation in OI [10]. PFN, compared to other adult fixation methods, offers stronger load sharing than elastic nails, which have limited rotational control and poor fatigue strength in adults with OI. In addition, while telescopic nails are considered ideal for pediatric OI cases, their use in adults is limited due to narrow medullary canals, increased implant failure, and difficulty in achieving proper anchorage. Therefore, PFN remains a reliable option for adult patients, particularly when deformity correction and whole-bone support are desired [11,12].

This case demonstrates that with meticulous pre-operative planning, careful implant selection, and intraoperative precision, stable fixation can be achieved even in severely osteoporotic and deformed bones. Closed reduction under fluoroscopic guidance and the minimally invasive nature of PFN insertion preserved periosteal blood supply and facilitated early healing. Progressive radiographic consolidation by 8 weeks and the ability to return to full weight-bearing by 5 months underscore the implant’s functional effectiveness in promoting early mobilization – an essential factor in minimizing refracture risk, preventing disuse osteopenia, and restoring pre-injury activity levels [3,13].

However, several limitations must be acknowledged. As a single-case report, the findings cannot be generalized to all patients with OI due to the heterogeneous nature of the disease, varying degrees of bone fragility, deformities, and previous fracture histories. The absence of a comparison or control group limits the ability to draw conclusions regarding the superiority of PFN over alternative methods. Although functional recovery was satisfactory, standardized outcome scoring systems such as the lower extremity functional scale, short form survey-36, or radiological union scores were not used, limiting objective assessment. The lack of advanced biomechanical or radiological evaluation (computed tomography scan and bone mineral density analysis) and the absence of genetic testing (COL1A1/COL1A2 mutation confirmation) also reflect resource limitations rather than methodological oversight. In addition, the relatively short follow-up period of 5 months restricts the assessment of long-term implant survival, deformity recurrence, refracture rates, or late complications such as screw migration or nail fatigue failure. Reporting bias may also be present, as rare successful outcomes may not reflect the full spectrum of challenges associated with surgery in OI patients.

Despite these limitations, this case adds to the growing body of evidence supporting intramedullary nailing, particularly PFN, as an effective option for adult OI patients with femoral fractures. By providing stable fixation, facilitating early mobilization, and spanning the entire femur to reduce future fracture risk, PFN represents a valuable tool in the surgical management of OI [14]. Continued reporting of similar cases, ideally with long-term functional scores and genetic/molecular correlation, will help strengthen clinical understanding and guide optimal implant selection in this rare but complex condition.

Intramedullary nailing is highly effective for managing fractures and deformities in OI, providing stable fixation, promoting early mobilization, and reducing recurrence risk. Careful surgical planning and post-operative monitoring are essential to minimize complications. This approach significantly improves functional outcomes and quality of life for OI patients, emphasizing the importance of tailored, multidisciplinary management to address the complex orthopedic challenges associated with the disorder.

Intramedullary fixation with a proximal femoral nail provides stable, load-sharing support in adults with osteogenesis imperfecta, enabling early mobilization even in the presence of severe osteopenia and deformity, thereby decreasing morbidity and further complications . Careful implant selection and minimally invasive techniques are essential to achieving reliable outcomes in this complex patient group.

References

- 1. Sofield HA, Millar EA. Fragmentation, realignment, and intramedullary rod fixation of deformities of the long bones in children. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1959;41:1371–1391. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 2. Sahu RL. Treatment concepts of osteogenesis imperfecta. Zahedan J Res Med Sci. 2011;14:e93429. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 3. Göçer H, Ulusoy S, Çıraklı A, Kaya İ, Dabak N. Intramedullary nailing of deformity and fracture in a patient with osteogenesis imperfecta. Med Bull Haseki. 2014;52:126–129. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 4. Cheung MS, Glorieux FH, Rauch F. Surgical management of osteogenesis imperfecta: a review of techniques and outcomes. Bone Joint J. 2014;96-B(11):1525–1532. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 5. Lee CL, Liu SC, Yang CY, Chuang CK, Lin HY, Lin SP. Incidence and treatment of adult femoral fractures with osteogenesis imperfecta: an analysis of a center of 72 patients in Taiwan. Int J Med Sci. 2021;18:1240–1246. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 6. Goudriaan WA, Harsevoort GJ, van Leeuwen M, Franken AA, Janus GJ. Incidence and treatment of femur fractures in adults with osteogenesis imperfecta: an analysis of an expert clinic of 216 patients. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. 2020;46:165–171. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 7. Rauch F, Glorieux FH. Osteogenesis imperfecta. Eur J Med Genet. 2014;57(7):348–355. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 8. Pous L, et al. Surgical treatment of fractures in osteogenesis imperfecta: a review. Curr Orthop Pract. 2018;29(4):307–314. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 9. Dimeglio A, Canavese F. Deformity correction and fracture management in osteogenesis imperfecta. Eur Spine J. 2015;24(11):2561–2569. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 10. Leithner A, Bernhardt GA, Högler P, et al. Surgical management of long bone deformities in osteogenesis imperfecta. Injury. 2020;51(11):2565–2572. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 11. Zäpfel N, Semler O, Rupprecht M, et al. Postoperative management and rehabilitation in osteogenesis imperfecta. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2020;478:290–299. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 12. Steinborn J, Kröber M, Semler O, Mäurer M. Surgical techniques and postoperative care in osteogenesis imperfecta. Orthop Clin North Am. 2020;51(4):485–496. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 13. Roca A, Barber I, Masquijo J, Bassini O. Early mobilization after intramedullary nailing in osteogenesis imperfecta patients. J Pediatr Orthop. 2020;40(3):e207–e212. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 14. Dimeglio A, Canavese F. Deformity correction and fracture management in osteogenesis imperfecta. Eur Spine J. 2015;24(11):2561–2569. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 15. Ward LM, Munns C, Rauch F, et al. Intramedullary rodding in osteogenesis imperfecta: techniques and outcomes. J Bone Miner Res. 2021;36(3):436–448. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]