Recognition of the “Spiderman Sign” may facilitate early diagnosis of rare, simultaneous flexor tendon injuries of the index and little fingers.

Dr. Riven Ragunandan, Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Charlotte Maxeke Johannesburg Academic Hospital, 7 York Road, Parktown, Johannesburg, 2193, South Africa. E-mail: riven52@gmail.com

Introduction: Flexor tendon injuries in Zone II remain among the most technically demanding conditions in hand surgery. Simultaneous involvement of the index and little fingers is rare and functionally disabling.

Case Report: A 56-year-old right-hand dominant male sustained transverse volar lacerations to the index and little fingers following a “panga” assault. Examination revealed a distinctive posture where the index and little fingers remained extended while the middle and ring fingers flexed, mimicking the Spiderman web-shooting gesture. Operative exploration confirmed complete transection of the flexor digitorum superficialis (FDS) and flexor digitorum profundus of the index finger and isolated FDS transection of the little finger. Tendon repair using a four-strand core technique with epitendinous reinforcement was performed, followed by early mobilization. At 12 weeks, the patient regained composite flexion, grip strength, and functional independence.

Conclusion: The “Spiderman Sign” represents a novel diagnostic clue for combined index and little finger tendon injuries. Early recognition, robust surgical repair, and structured rehabilitation led to excellent outcomes in this case.

Keywords: Flexor tendon injury, zone II, index finger, little finger, Spiderman sign, hand trauma.

Flexor tendon injuries are relatively uncommon but carry disproportionately high morbidity due to the intricate anatomy and biomechanical function of the flexor system, particularly within Zone II, historically referred to as “no man’s land” [1,2]. These injuries remain surgically challenging because the tendons pass through a confined fibro-osseous tunnel, increasing the risk of adhesions, repair failure, and functional stiffness [3].

From a functional perspective, each digit plays a critical role in hand biomechanics. The index finger contributes to precision pinch and fine dexterity, while the little finger provides nearly one-third of overall grip strength and augments hand stability [4,5]. Consequently, simultaneous disruption of these two digits severely compromises both dexterity and power grip. Previous reports have described isolated flexor tendon injuries to the index or little finger, but combined ipsilateral involvement of both digits is rare [6,7].

Flexor tendon repair techniques have evolved substantially, with multi-strand core repairs combined with epitendinous suturing now regarded as the gold standard to improve repair strength and allow early mobilization [8,9,10,11]. Rehabilitation protocols, including early active mobilization, are crucial to minimize adhesion formation and optimize tendon glide [12,13,14].

We report a rare case of simultaneous index and little finger Zone II flexor tendon injuries producing a distinctive clinical posture that we have termed the “Spiderman Sign.” To the best of our knowledge, this presentation has not been described in the literature and may serve as a useful diagnostic marker.

A 56-year-old right-hand dominant male presented to the emergency department 6 h following an assault with a “panga,” a broad machete-like knife commonly used in Southern Africa as both a farming tool and a weapon. The patient reported that during the attack, the weapon was forcibly withdrawn while his hand was clenched in a fist. This mechanism resulted in transverse volar lacerations across the left index and little fingers, specifically within flexor tendon Zone 2. Given the anatomical complexity of this zone, the injuries were considered clinically significant and required urgent orthopedic specialist attention.

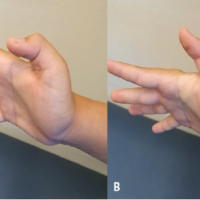

On arrival, a detailed hand examination was undertaken. The patient’s resting cascade demonstrated a striking abnormality: the index and little fingers lay extended, while the middle and ring fingers maintained their natural flexed posture. This pattern produces a distinctive clinical posture that we have termed the “Spiderman Sign.”

Individual digit testing confirmed this suspicion. In the index finger, there was complete loss of flexion at both the proximal interphalangeal joint (PIPJ) and the distal interphalangeal joint (DIPJ). The absence of movement at both joints indicated a combined disruption of the flexor digitorum superficialis (FDS) and the flexor digitorum profundus (FDP) tendons.

In the little finger, the patient was unable to flex the PIPJ but retained flexion at the DIPJ. This finding corresponded to an isolated transection of the FDS with preservation of the FDP. Importantly, perfusion was intact, with brisk capillary refill, and no neurovascular deficits were detected. Sensation was preserved along the digital nerve territories.

Radiographs of the hand were obtained to exclude associated bony injuries or retained foreign material. No fractures or foreign bodies were identified.

Initial management in the emergency department followed standard wound care protocols, including administration of broad-spectrum intravenous antibiotics, tetanus prophylaxis, and adequate analgesia. The wounds were thoroughly irrigated with normal saline to minimize contamination, appositional skin sutures were placed with Nylon 4.0, and the hand was immobilized in a protective splint to prevent further tendon retraction. 12 h after injury, he was taken for urgent exploration and tendon repair (Fig. 1).

Figure 1: Post-injury image with appositional skin sutures: Left hand volar and ulnar lateral aspect.

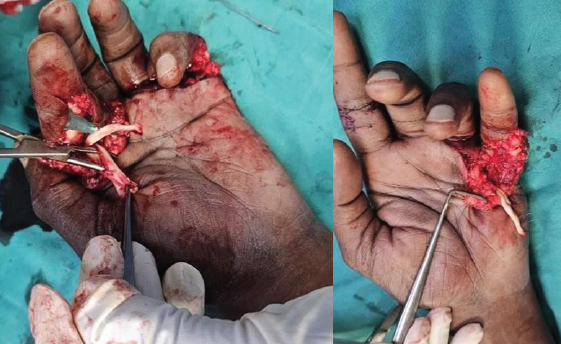

Intraoperatively, Brunner’s zig-zag incisions were employed to allow wide exposure of the flexor tendon sheath while minimizing contracture risk during healing.

- In the index finger, both the FDS and FDP tendons were found completely transected within Zone II. The A2 pulley was intact (an important finding as preservation of this pulley is critical for tendon gliding and prevention of bowstringing) (Fig. 2).

- In the little finger, the FDS was completely transected, while the FDP was intact. Again, the A2 pulley remained preserved (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: Intraoperative volar image: Left hand index and little finger.

No additional injuries to the neurovascular bundles were identified.

All flexor tendons were found to have retracted proximally beyond the pulley system, creating a significant challenge during retrieval. A 12 Fr pediatric feeding tube was gently passed through the A2 pulley (distal to proximal), and the retracted tendon ends were secured to it with a Nylon 4.0 suture. This allowed controlled traction of both the feeding tube and tendons, facilitating their smooth passage through the A2 pulley back into their anatomical positions. Once delivered distally, the tendons were temporarily stabilized with hypodermic needles into the surrounding soft tissue to prevent further retraction while repairs were undertaken [15].

Tendon repairs were carried out using a four-strand core suture technique (Prolene 3.0), which provides greater tensile strength compared to traditional two-strand methods. This was reinforced with epitendinous circumferential sutures (Nylon 5.0), improving tendon coaptation and reducing gapping at the repair site. The repairs were tested intraoperatively for smooth gliding through the pulley system, confirming that there was no impingement or undue resistance (Fig. 3).

Figure 3: Intraoperative volar and radial lateral: Left hand post tendon repair.

Pulley integrity was meticulously preserved throughout the procedure. This step was vital, as unnecessary venting or damage to the A2 pulley can compromise the long-term biomechanics of tendon motion. Following satisfactory tendon repair, interrupted skin sutures were done (Nylon 4.0).

The patient’s post-operative rehabilitation followed the early active place-and-hold protocol described by Trumble et al., which has demonstrated superior functional outcomes after Zone II flexor tendon repair. Under this protocol, the hand was immobilized in a dorsal blocking splint to limit wrist extension and protect the repair while permitting controlled digital motion. Beginning in the early post-operative period, the patient performed passive flexion of the injured digits followed by active “place-and-hold” contraction, generating moderate force and high tendon excursion within a protected range [11]. These exercises were performed repeatedly throughout the day with supervision of an experienced occupational therapist at the hospital. This evidence-based regimen promotes tendon glide, reduces adhesion formation, and enhances interphalangeal joint motion.

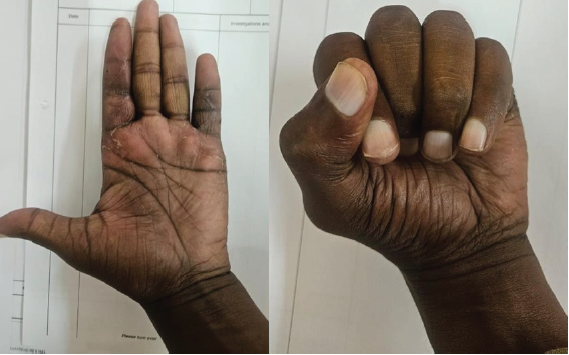

At the 12-week follow-up, the patient demonstrated excellent recovery. Both the index and little fingers achieved composite flexion, with restoration of coordinated motion across the interphalangeal and metacarpophalangeal joints. Grip strength testing showed near-symmetrical function compared to the contralateral hand, allowing the patient to perform activities of daily living and occupational tasks without significant limitation (Fig. 4).

Figure 4: Post-rehabilitation volar image: Left hand with extended and flexed fingers.

The surgical wounds had healed well, with no evidence of infection, tendon rupture, or wound dehiscence. Furthermore, there were no complications such as significant adhesion formation or joint stiffness, which are common concerns in Zone II tendon repairs. The patient reported satisfaction with the functional outcome and was able to return to his pre-injury activities with only minimal residual discomfort.

Zone II tendon injuries continue to pose technical challenges due to the confined anatomy, close relationship between tendons and pulleys, and high risk of adhesion formation [5,6]. The importance of meticulous repair cannot be overstated, as suboptimal outcomes are often linked to gapping or rupture at the repair site. Advances in surgical techniques, including four strand core sutures combined with epitendinous reinforcement, have enhanced repair strength and provided a foundation for early mobilization, which is now the cornerstone of rehabilitation [7,8].

The role of rehabilitation is equally critical. Early active mobilization protocols reduce adhesion formation and improve tendon glide, leading to better functional outcomes [9,10,11,16].

Functionally, the loss of the index finger compromises pincer grip and fine motor tasks, while the little finger contributes to grip strength [4,12]. Simultaneous injury to both digits therefore creates a compounded disability, magnifying the clinical importance of accurate diagnosis and effective management. In our case, the distinctive hand posture resembling the popular “Spiderman” web shooting gesture provided a novel clinical clue. Recognizing such a sign at presentation could allow clinicians to suspect dual tendon injuries even before formal imaging or exploration.

This case highlights three key points: (1) Careful clinical observation remains invaluable in trauma assessment, (2) robust repair with multi-strand techniques permits early motion without compromising structural integrity, and (3) functional outcomes can be excellent with timely surgery and structured rehabilitation. To the best of our knowledge, this “Spiderman Sign” has not been previously described, and its recognition could serve as a quick, practical aid to diagnosis.

The “Spiderman Sign” is a novel clinical finding associated with simultaneous ipsilateral index and little finger flexor tendon injuries in Zone II. Recognition of this posture may expedite diagnosis, while robust repair and structured rehabilitation enable favorable outcomes.

Recognition of the “Spiderman Sign” may assist in timely diagnosis of simultaneous index and little finger tendon injuries, which are otherwise rare and functionally disabling.

References

- 1. Tang JB. Flexor tendon injuries. Clin Plast Surg 2019;46:295-306. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 2. Manske PR, Lesker PA. Flexor tendon nutrition. Hand Clin 1985;1:13-24. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 3. Doyle JR. Anatomy of the finger flexor tendon sheath and pulley system. J Hand Surg Am 1988;13:473-84. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 4. Mogk JP, Keir PJ. The effects of posture on forearm muscle loading during gripping. Ergonomics 2003;46:956-75. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 5. Riddick A, Grant D, Traynor I, Ng CY. The functional importance of the little finger: A clinical and biomechanical perspective. J Hand Surg Eur 2014;39:566-72. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 6. Dy CJ, Hernandez-Soria A, Ma Y, Roberts TR, Daluiski A. Complications after flexor tendon repair: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Hand Surg Am 2012;37:543-51.e1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 7. Strickland JW. Development of flexor tendon surgery: Twenty-five years of progress. J Hand Surg Am 2000;25:214-35. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 8. Savage R. In vitro studies of a new method of flexor tendon repair. J Hand Surg Br 1985;10:135-41. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 9. Silfverskiöld KL, May EJ, Törnkvist H. Flexor tendon repair in zone II with a new suture technique and an early mobilization program. J Hand Surg Am 1992;17:987-95. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 10. Kleinert HE, Kutz JE, Ashbell TS, Martinez E. Primary repair of lacerated flexor tendons in “no man’s land.” J Bone Joint Surg Am 1967;49:577-84. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 11. Tang JB, Lalonde D, Harhaus L, Sadek AF, Moriya K, Pan ZJ. Flexor tendon repair: Recent changes and current methods. J Hand Surg Eur Vol 2022;47:31-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 12. Trumble TE, Vedder NB, Seiler JG, Hanel DP, Diao E, Pettrone S. Zone-II flexor tendon repair: A randomized prospective trial of active place-and-hold therapy compared with passive motion therapy. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2010;92:1381-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 13. Chesney A, Chauhan A, Kattan A, Farrokhyar F, Thoma A. Systematic review of flexor tendon rehabilitation protocols in zone II of the hand. Plast Reconstr Surg 2011;127:1583-92. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 14. Xu H, Huang X, Guo Z, Zhou H, Jin H, Huang X. Outcome of surgical repair and rehabilitation of flexor tendon injuries in Zone II of the hand: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J Hand Surg Am 2023;48:407.e1-407.11. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 15. Kadar A, Gur S, Schermann H, Iordache SD. Techniques for retrieval of lacerated flexor tendons: A scoping review. Plast Surg (Oakv) 2024;32:127-37. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 16. Chevalley S, Tenfält M, Åhlén M, Strömberg J. Passive mobilization with place and hold versus active motion therapy after flexor tendon repair: A randomized trial. J Hand Surg Am 2022;47:348-57. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]