Selumetinib therapy in pediatric patients with Neurofibromatosis Type 1 may be associated with impaired bone healing and pathological fractures, particularly in the setting of mechanical stress such as limb lengthening.

Dr. Zahra Safari, Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Aalborg University Hospital, 9000, Aalborg, Denmark. E-mail: z.safari@rn.dk

Introduction: Neurofibromatosis Type 1 (NF1) is a genetic disorder that may lead to the development of plexiform neurofibromas (PNs). Selumetinib, a selective mitogen-activated protein kinase (MEK1/2) inhibitor, has shown clinical benefit in shrinking inoperable PNs. However, its long-term effects on the skeleton remain unclear. This case describes impaired bone healing and pathological fractures following limb lengthening in a child with NF1 receiving prolonged selumetinib therapy.

Case Report: A 5-year-old boy with genetically confirmed NF1 and left lower limb PN-induced overgrowth presented with a 4.5 cm limb length discrepancy. The patient had been receiving selumetinib (20 mg twice daily) without a clinically significant reduction in the size of the PNs. Lengthening was performed on a short healthy lower leg with an external fixator that did not include the femur. A distal femoral fracture occurred 3 weeks postoperatively on the same side as the lower leg lengthening was performed, and was treated with K-wire fixation. Despite healing, a refracture occurred 2 months later. In addition, delayed bone healing was observed for the tibial lengthening regenerate, and progressive valgus deformity and fibular migration developed. Selumetinib was discontinued due to adverse effects and suspected contribution to impaired bone healing.

Conclusion: In pediatric NF1 patients treated with selumetinib, fracture and impaired bone healing may be rare side effects, especially during limb lengthening. These findings highlight the importance of closely monitoring bone health in NF1 patients on MEK inhibitors, particularly when undergoing orthopedic procedures.

Keywords: Neurofibromatosis Type 1, selumetinib, pathological fracture, plexiform neurofibroma, limb lengthening.

Neurofibromatosis Type 1 (NF1) is an autosomal dominant genetic disorder, with an incidence of approximately 1 in 3000 individuals worldwide [1]. It results from mutations in the NF1 gene located on chromosome 17, which encodes neurofibromin, which is a tumor suppressor that negatively regulates the Ras/MAPK pathway [2]. Major NF1 features include cafe-au-lait macules, skinfold freckling, Lisch nodules, neurofibromas, plexiform neurofibromas (PNs), typical bone abnormalities, and optic pathway glioma [2]. PNs are benign but often progressive tumors that arise from nerves and affect approximately 30-50% of patients [3]. Typically congenital or appearing in early childhood, they tend to grow most rapidly in children under the age of five [2]. In Denmark, the prevalence of NF1 is approximately 1 in 5,500 individuals. Among those diagnosed with NF1, at least one PN is present in 38% of children and 65% of adults [3]. Until recently, surgery was one of the only treatments for PNs. However, mitogen-activated protein kinase (MEK) inhibitors, particularly selumetinib, have emerged as a targeted therapeutic option for treating inoperable PNs in patients with NF1 [4]. Selumetinib is a selective MEK1/2 inhibitor that has demonstrated significant efficacy in reducing PN volume and improving clinical symptoms, as supported by clinical studies and consensus reports [5]. Despite its therapeutic promise, concerns have been raised regarding adverse events associated with selumetinib. The most frequently reported toxicities include gastrointestinal disturbances (nausea, vomiting, diarrhea), dermatological reactions (rash, acneiform dermatitis), and cardiotoxicity (decreased left ventricular ejection fraction) [4,5]. More recently, attention has turned toward potential skeletal side effects, particularly osteopenia, growth disturbance, and increased fracture risk in children [6]. The mechanisms underlying these skeletal effects are not fully understood. Experimental evidence suggests that MEK inhibition interferes with endochondral ossification and fracture healing. El-Hoss et al. demonstrated that MEK inhibitors, including selumetinib (AZD6244), slow cartilage remodeling during fracture healing by increasing soft callus cartilage volume, expanding the hypertrophic zone in growth plates, and reducing osteoclast surface in both calluses and growth plates, thereby hindering normal bone repair [7]. These findings raise particular concern for skeletally immature NF1 patients who are already predisposed to bone fragility and deformity. We present a case of a pediatric NF1 patient treated with selumetinib, who developed rare complications such as delayed bone healing, proximal migration of the distal fibula, valgus deformity of the tibia, and pathological femoral fractures during limb lengthening of the tibia. CARE guidelines were followed to report this case.

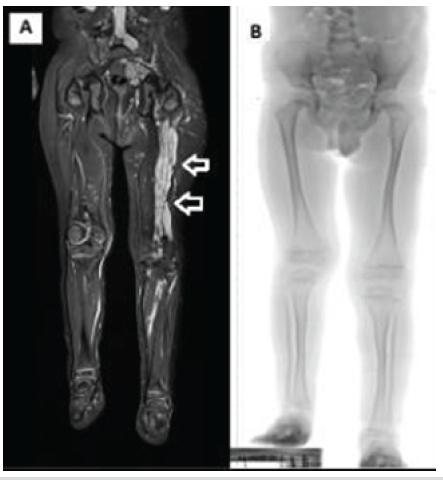

A 5-year-old boy with genetically confirmed NF1 has been under regular follow-up in the pediatric orthopedic department. The patient was diagnosed with NF1 at 1.5 years of age after a positive family history (father NF1 diagnosis). Considering clinical examination, the patient had a small café au lait spot (<5 mm) on the back, no scoliosis, or congenital pseudarthrosis of the tibia. However, a PN involving the left lower limb (Fig. 1a) had led to increased local vascularity, resulting in soft tissue and osseous overgrowth of the affected limb. This progressive overgrowth had caused a limb length discrepancy (LLD) of approximately 4.5 cm, with the left leg being longer (Fig. 1b). The patient had been treated with selumetinib (20 mg twice daily) as part of ongoing treatment to inhibit growth of PN since the age of 3.5 years old, but without a significant reduction of the neurofibromas volume.

Figure 1: (a) Magnetic resonance imaging of both lower limbs showing extensive plexiform neurofibroma infiltration in the soft tissues of the left lower limb compared to the unaffected right side. (b) Standing radiograph, demonstrating limb length discrepancy, with the right lower limb being shorter by 4.5 cm.

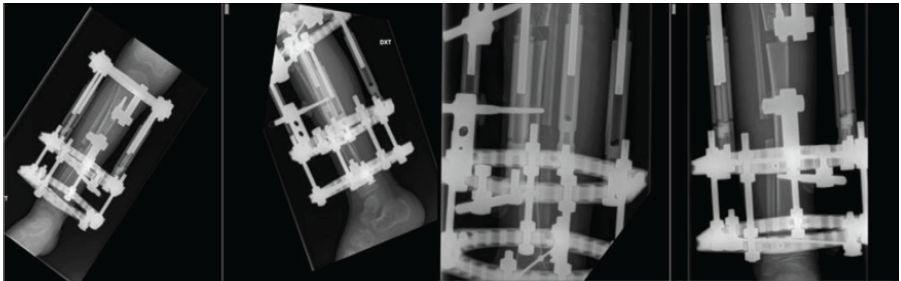

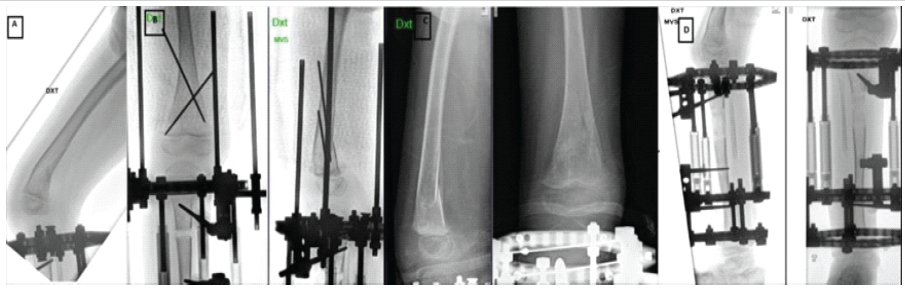

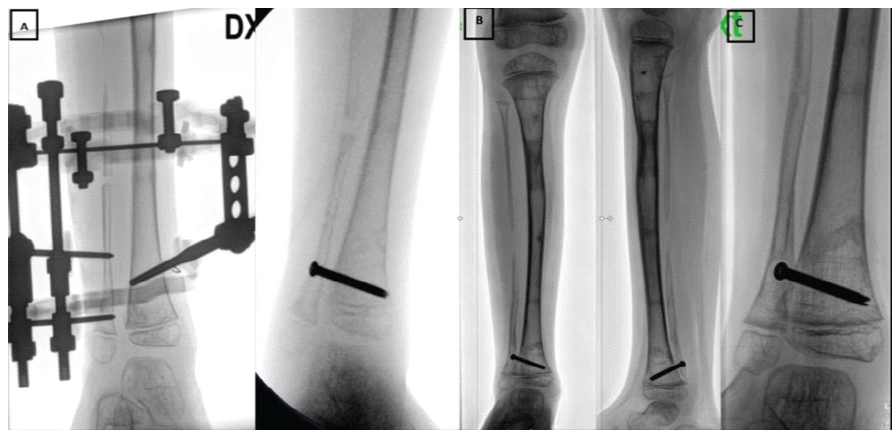

To correct the LLD, the patient underwent lengthening surgery of the short lower limb on the unaffected side with a circular external fixator. A low-energy proximal tibial osteotomy was performed, and an ostectomy of the fibula was made, and at the same time, both the proximal fibula and the distal fibula were fixated to the tibia with transosseous wires (Fig. 2). No surgery was performed on the femur, and the external fixator did not include the femur. Three weeks after surgery, the patient had a non-traumatic femoral fracture on the operated side (Fig. 3a). Given the absence of significant trauma and the presence of NF1 and MEK inhibitor therapy, the fracture was considered pathological. Management included plaster casting and K-wire fixation (Fig. 3b). Four weeks after fixation, plaster and K-wires were removed (Fig. 3c and d). Lengthening process resulted in a 4 cm gain, equivalent to 17% of the original tibial length (4/24 cm). Approximately 2 months after hardware removal, a refracture of the femur occurred at the same site (Fig. 4a), which was again treated with K-wire fixation and plaster (Fig. 4b).

Figure 2: Anteroposterior and lateral radiographic views of the right lower limb during tibial lengthening using a circular external fixator.

Figure 3: (a) Fracture of right distal femur (b) Anteroposterior and lateral radiographs showing k-wire fixation following femoral fracture during limb lengthening (c) Fracture healing, after 4 weeks of fixation (plaster and k-wires removed) (d) Lengthening process during the same period.

Figure 4: (a) Refracture at the right distal femur 2 months after plaster and K-wire removal (b) Fracture fixation with K-wires and plaster (c) Valgus deformity of the right lower limb.

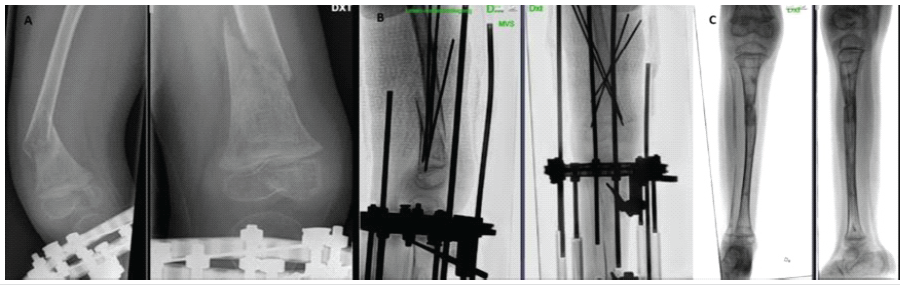

Four weeks later, the external fixator and K-wires were removed, and a long-leg cast was applied. During the subsequent 5 weeks of immobilization, the patient developed a progressive valgus deformity of the operated lower limb (Fig. 4c) and a proximal migration of the distal fibula suggesting instability at the distal tibiofibular joint. To address this, bone transport of the distal fibula (Fig. 5a) was performed. To maintain alignment, a distal positioning screw was inserted. However, the patient experienced recurrence of proximal fibular migration due to screw cut-out and fixation failure (Fig. 5b,c). Throughout the course of treatment, the contralateral limb with the PN remained skeletally unaffected.

Figure 5: (a) Bone lengthening of the right distal fibula (b) Proximal migration of the right distal fibula (c) Proximal fibular migration due to screw cut-out and fixation failure.

Future plans for treatment include hemiepiphysiodesis with eight-plate on the operated medial proximal tibia to adjust for valgus malalignment, followed by new bone transport of the distal fibula at a later stage. There is a possibility that LLD will increase again, and more surgeries will be needed, including epiphysiodesis of the longer right lower leg. This is because the left limb continues to overgrow compared to the right, so despite the 4 cm gained, the overgrowth persisted, resulting in a remaining leg length discrepancy of 2.5 cm at the latest follow-up at the age of 7 years. Selumetinib was discontinued after almost 3 years of treatment due to uncertainty about its long-term efficacy, along with the development of adverse effects, including skin rash and potential association with the non-traumatic fractures that occurred during the lengthening.

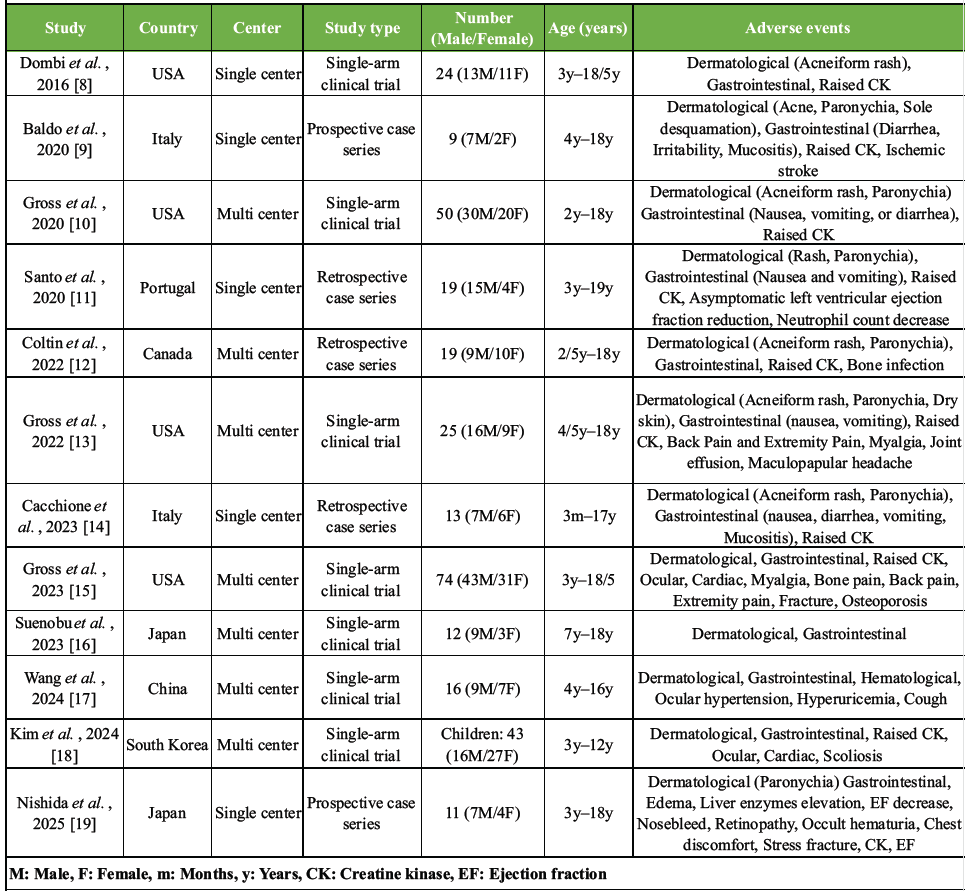

This case illustrates a pediatric NF1 patient undergoing selumetinib treatment who developed pathological fractures during limb lengthening surgery. The main question that arose was the cause of the two fractures observed during the limb lengthening process. Different factors could have contributed to this event. Thus, several studies have shown that patients with NF1 exhibit significantly reduced bone mineral density from early childhood, especially of the femur, which may contribute to increased fracture risk and impaired bone remodeling, even in the absence of skeletal deformities [2]. However, what set this case apart from previously treated NF1 patients in our clinic was the concurrent treatment with selumetinib, and that pathological fractures occurred at the untreated distal femur. Although MEK inhibitors have been helpful in treating NF1 patients with inoperative PNs, there is some evidence that chronic MEK inhibition could impair bone remodeling and increase fracture risk in other settings. Dumas et al. [6] described two patients with advanced melanoma who were treated long-term with MEK inhibitors that developed fractures due to osteopenia. Since there were no other common causes of osteoporosis or signs of cancer spreading to the bones, the authors suggested that the MEK inhibitors likely caused the bone loss. We conducted a literature review of adverse events associated with selumetinib treatment in pediatric patients with NF1, identifying 12 relevant studies [8-19]. Table 1 summarizes the adverse events reported across these studies. The most frequently observed adverse events were cutaneous reactions, gastrointestinal symptoms, and elevated creatine kinase (CK) levels.

Table 1: Literature review of adverse effects of selumetinib in NF1 patients.

Musculoskeletal/bone-related adverse events were reported in 10 studies and comprised: 83 cases of elevated CK levels (9 studies), 1 fracture (specific type not mentioned), 1 stress fracture, 1 case of osteoporosis, 1 case of bone pain, 9 cases of extremity pain (3 studies), and 5 cases of back pain (2 studies). In Dombi et al.’s study, CK was elevated in 17 of the total 24 patients during selumetinib treatment. To determine the origin, CK isoenzyme analysis was performed in 17 patients, and it showed that the elevated CK was of skeletal muscle origin (CK-MM), not cardiac (CK-MB). However, the study does not mention any direct effect of the drug on skeletal muscles, nor does it clarify whether the CK elevation is associated with muscle pain or weakness [8]. In a long-term phase 1/2 trial of pediatric NF1 patients, Gross et al. [15] reported that musculoskeletal side effects, such as bone pain, fracture, and signs of bone loss (osteoporosis), gradually appeared during treatment, suggesting that prolonged use of selumetinib may weaken the bones over time. In a recent Japanese case series involving 11 pediatric NF1 patients treated with selumetinib, one patient discontinued the drug due to unexplained lower leg pain, which was later identified as a stress fracture likely caused by selumetinib [19]. All other studies reported musculoskeletal and bone-related adverse events without providing further commentary or explanation. In Denmark, treatment strategies for PNs included observation, surgical resection in symptomatic cases, and targeted medical therapy [3]. Selumetinib was introduced in Denmark in 2021 for children (≥3 years) with inoperable, symptomatic PNs, after EU approval. However, in May 2024, the Danish Medicines Council evaluated selumetinib for treating children with NF1 and inoperable symptomatic PN, with particular attention to its safety profile. Although selumetinib demonstrated potential in reducing tumor volume, the treatment was associated with a high incidence of adverse events. In the SPRINT [15] trial, 9% of patients required dose reductions due to treatment-related toxicity, and 12% discontinued treatment entirely. While most adverse events were mild-to-moderate in severity, some were clinically significant and impacted treatment adherence. Due to these safety concerns, the uncertainty regarding long-term effects, and the high cost of therapy, the Council did not recommend selumetinib for routine use. Instead, they advised awaiting additional efficacy and safety data, as well as a reduction in cost, before reconsidering its recommendation. Overall, while selumetinib shows promise in treating NF1-related tumors, its potential impact on bone health warrants caution. Until future studies clarify selumetinib long-term effects on bone health in children, close monitoring and prompt management of bone-related symptoms remain essential. A limitation of the presented case is that the definitive assessment of bone health parameters, such as bone mineral density or metabolic markers, was not available at the time of intervention. Even though intraoperative findings and radiographic appearance suggested normal bone quality, this missing data limits the ability to directly attribute the cause to one factor over another. Based on this experience, we recommend thorough preoperative evaluation of bone quality in patients with NF1, particularly those receiving MEK inhibitors, before undertaking limb lengthening procedures.

This case highlights a very rare adverse event with delayed bone healing during limb lengthening and pathological fractures in a pediatric NF1 patient treated with selumetinib. It underscores the need for careful monitoring of bone quality and mechanical stress in such patients and calls for further research into the effects of MEK inhibitors on bone healing and strength.

In pediatric patients with NF1 undergoing selumetinib therapy, clinicians should be aware of the potential for impaired bone healing and increased fracture risk, especially during limb lengthening procedures. We recommend that selumetinib therapy is discontinued prior to limb lengthening to decrease the risk of bony complications.

References

- 1. Uusitalo E, Leppävirta J, Koffert A, Suominen S, Vahtera J, Vahlberg T, et al. Incidence and mortality of neurofibromatosis: A total population study in Finland. J Invest Dermatol 2015;135:904-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 2. Gutmann DH, Ferner RE, Listernick RH, Korf BR, Wolters PL, Johnson KJ. Neurofibromatosis type 1. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2017;3:17004. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 3. Ejerskov C, Farholt S, Nielsen FS, Berg I, Thomasen SB, Udupi A, et al. Clinical characteristics and management of children and adults with neurofibromatosis type 1 and plexiform neurofibromas in Denmark: A nationwide study. Oncol Ther 2023;11:97-110. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 4. De Blank PM, Gross AM, Akshintala S, Blakeley JO, Bollag G, Cannon A, et al. MEK inhibitors for neurofibromatosis type 1 manifestations: Clinical evidence and consensus. Neuro Oncol 2022;24:1845-56. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 5. Han Y, Li B, Yu X, Liu J, Zhao W, Zhang D, et al. Efficacy and safety of selumetinib in patients with neurofibromatosis type 1 and inoperable plexiform neurofibromas: A systematic review and meta analysis. J Neurol 2024;271:2379-89. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 6. Dumas M, Laly P, Gottlieb J, Vercellino L, Paycha F, Bagot M, et al. Osteopenia and fractures associated with long-term therapy with MEK inhibitors. Melanoma Res 2018;28:641-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 7. El-Hoss J, Kolind M, Jackson MT, Deo N, Mikulec K, McDonald MM, et al. Modulation of endochondral ossification by MEK inhibitors PD0325901 and AZD6244 (Selumetinib). Bone 2014;59:151-61. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 8. Dombi E, Baldwin A, Marcus LJ, Fisher MJ, Weiss B, Kim AE, et al. Activity of selumetinib in neurofibromatosis type 1-related plexiform neurofibromas. N Engl J Med 2016;375:2550-60. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 9. Baldo F, Grasso AG, Cortellazzo Wiel L, Maestro A, Trojniak MP, Murru FM, et al. Selumetinib in the treatment of symptomatic intractable plexiform neurofibromas in neurofibromatosis type 1: A prospective case series with emphasis on side effects. Paediatr Drugs 2020;22:417-23. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 10. Gross AM, Wolters PL, Dombi E, Baldwin A, Whitcomb P, Fisher MJ, et al. Selumetinib in children with inoperable plexiform neurofibromas. N Engl J Med 2020;382:1430-42. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 11. Santo VE, Passos J, Nzwalo H, Carvalho I, Santos F, Martins C. Selumetinib for plexiform neurofibromas in neurofibromatosis type 1: A single-institution experience. J Neurooncol 2020;147:459-63. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 12. Coltin H, Perreault S, Larouche V, Black K, Wilson B, Vanan MI, et al. Selumetinib for symptomatic, inoperable plexiform neurofibromas in children with neurofibromatosis type 1: A national real-world case series. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2022;69:e29633. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 13. Gross AM, Glassberg B, Wolters PL, Dombi E, Baldwin A, Fisher MJ, et al. Selumetinib in children with neurofibromatosis type 1 and asymptomatic inoperable plexiform neurofibroma at risk for developing tumor-related morbidity. Neuro Oncol 2022;24:1978-88. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 14. Cacchione A, Fabozzi F, Carai A, Colafati GS, Baldo GD, Rossi S, et al. Safety and efficacy of MEK inhibitors in the treatment of plexiform neurofibromas: A retrospective study. Cancer Control 2023;30:10732748221144930. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 15. Gross AM, Dombi E, Wolters PL, Baldwin A, Dufek A, Herrera K, et al. Long-term safety and efficacy of selumetinib in children with neurofibromatosis type 1 on a phase 1/2 trial for inoperable plexiform neurofibromas. Neuro Oncol 2023;25:1883-94. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 16. Suenobu S, Terashima K, Akiyama M, Oguri T, Watanabe A, Sugeno M, et al. Selumetinib in Japanese pediatric patients with neurofibromatosis type 1 and symptomatic, inoperable plexiform neurofibromas: An open-label, phase I study. Neurooncol Adv 2023;5:vdad054. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 17. Wang Z, Zhang X, Li C, Liu Y, Ge X, Zhao J, et al. Safety, pharmacokinetics and efficacy of selumetinib in Chinese adult and paediatric patients with neurofibromatosis type 1 and inoperable plexiform neurofibromas: The primary analysis of a phase 1 open-label study. Clin Transl Med 2024;14:e1589. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 18. Kim H, Yoon HM, Kim EK, Ra YS, Kim HW, Yum MS, et al. Safety and efficacy of selumetinib in pediatric and adult patients with neurofibromatosis type 1 and plexiform neurofibroma. Neuro Oncol 2024;26:2352-63. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 19. Nishida Y, Nonobe N, Kidokoro H, Kato T, Takeichi T, Ikuta K, et al. Selumetinib for symptomatic, inoperable plexiform neurofibromas in pediatric patients with neurofibromatosis type 1: The first single-center real-world case series in Japan. Jpn J Clin Oncol 2025;55:372-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]