Indigenously developed negative pressure wound dressing (SNPWD) provides a safe, effective, and low-cost alternative to commercial NPWT systems, achieving comparable wound healing and infection control in resource-limited settings.

Dr. Sahil Maingi, Department of ENT, Dayanand Medical College and Hospital, Ludhiana, Punjab, India. E-mail: sahil201191@gmail.com

Introduction: Negative pressure wound therapy (NPWT) has emerged as a highly effective technique for managing chronic non-healing wounds. However, the high cost and limited accessibility of commercial NPWT systems restrict their routine use in resource-constrained settings. This study aims to evaluate the efficacy of an indigenously developed simplified negative pressure wound dressing (SNPWD) for wound management in a low-resource environment.

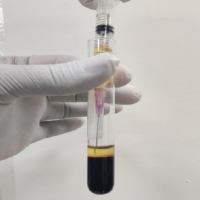

Materials and Methods: This prospective cohort study was conducted on 24 patients with a mean wound size pre-SNPWD being 73.5cm2 in the Department of Orthopaedics at a tertiary care hospital. Final wound area, total duration of SNPWD application, number of dressing changes, and the exudate collection, along with culture report, were documented for outcome comparison with data from existing NPWT literature.

Results: The decrease in mean wound surface area after SNPWD application in our study was 27.2%. The mean duration of SNPWD application, that is, the time taken for development of healthy granulation tissue, ranged from 8 to 27 days, the mean duration being 16.5 days. The mean number of dressings applied per patient was 5.3. The mean amount of exudates collected in the canister decreased by 58% as compared to pre-SNPWD. The post-SNWPD culture report of wounds was sterile in 96% of cases, as compared to only 37.5% sterile culture reports before applying SNPWD.

Conclusion: The SNPWD is a safe, effective, and cost-efficient alternative to commercial NPWT systems. With comparable clinical outcomes and significantly lower cost, SNPWD holds strong potential for widespread use in managing complex wounds, especially in resource-limited settings.

Keywords: Wound healing, negative pressure wound dressing, vacuum-assisted closure, infection.

Wound healing is a complex phenomenon and requires a multidisciplinary approach for optimum results. Modern wound healing concepts [1,2,3] include different types of moist dressings and topical agents, but only a few of them have a proven efficacy over traditional wet gauze dressings. One such modality is negative pressure wound therapy (NPWT), which uses a controlled negative pressure of a suction machine to promote wound healing. It’s easy to use nature and high efficacy makes it a suitable method for wound management. The conventional method for management of wounds involves frequent change of dressing and debridement until the wound becomes healthy. However, it has been reported in studies by Caudle and Stern [4] that these dressings have a slower rate of skin coverage and take a longer duration for wound healing, which prolongs the hospital stay of patients. NPWT or vacuum-assisted closure (VAC) is a method of wound management for exudative, chronic non-healing, or infected wounds. These wounds lead to hazardous outcomes, such as prolonged hospitalization, amputation, and sepsis, depending on various host and environment factors. Such wounds are usually associated with extensive soft tissue loss and require a reconstructive surgery, which cannot be immediately done due to the presence of infection, necrotic material, and the large size of these wounds, thus they require topical dressings until surgical closure is possible [5]. NPWT is a relatively newer, adjunctive, and non-invasive method to dress those wounds that are not amenable to primary surgical closure. The NPWT involves the use of a controlled intermittent sub-atmospheric pressure sealed dressing connected to a suction machine to drain the exudates and remove infection load. The beneficial mechanism of these dressings, as described by Argenta et al., [6] include reduction in the amount of exudates, interstitial pressure, and infection load over the wound surface. It also causes a reduction in cytokines, collagenases, and elastase over the wound surface and increases fibroblast and endothelial cell proliferation, causing wound contracture and angiogenesis, which leads to early wound healing. There are a lot of commercially available NPWT options in the market. All these have a common mechanism to provide intermittent suction to drain exudates and decrease infection load. The intermittent suction is preferred over continuous suction because there is more contraction of wound edges and more rapid formation of the granulation tissue when intermittent suction is used as compared to continuous suction. Leukocyte infiltration and tissue disorganization are also prominent with intermittent suction as described in studies by Malmsjo et al., [7] These dressings use a complex technology to provide intermittent suction, which involves using a real-time pressure feedback system that adjusts the pump output, compensating for wound distance, wound position, exudate characteristics, and patient movement. The advanced technology to provide intermittent suction results in a very high cost of equipment of these VAC dressings, thus limiting its routine use in low-resource settings. In our study, a timer switch is used to convert a simple portable suction machine to a negative pressure wound dressing. Such a simplified method creates an intermittent vacuum at a set negative pressure. This study is proposed to assess the effectiveness of such a low-cost, indigenously developed and simplified negative pressure wound dressing (SNPWD) in the management of wounds.

The negative pressure source was a portable suction machine in which the pressure gauge was adjusted to provide appropriate suction of 100–120 mm hg. The machine did not break down or overheat throughout the dressing period.

The second component was the electric timers switch with adjustable on and off timings. It was completely safe and did not pose any electric hazard to the patient. The working voltage of the switch was around 12V. The timer switch was set manually to provide the supply to the suction machine for 5 min (on cycle) and then cut it for 3 min (off cycle). The timer switch and suction machine functioned as independent entities. This had the advantage that when a breakdown of the system occurred due to a technical fault in either of the two, one component could be repaired without affecting the other. The dressing material used was procured in the hospital from a readily available source. It consists of pre-sterilized foam with a pore size between 400 and 600 microns, an adhesive drape to cover the foam, and a connecting tube attached to the adhesive drape. A major challenge while applying the dressing was to prevent air leaks. Most of the small air leaks developed at anatomically challenging sites, such as areas where tubing exits the adhesive drape, areas having irregular contours, such as the anus and perineum, and near external fixator pins. Such leaks were identified by Presence of audible tones at air leaks Non-compression of foam despite adequate negative pressure. After the identification of the leak site, sealing was done at that site by a plastic adhesive drape. It survived the difficult wound environment and helped in maintaining an airtight seal for 3 days. The efficacy of this SNPWD was evaluated in terms of reduction in wound surface area till wound bed is covered by healthy granulation tissue, the time for which it was applied to attain adequate wound healing, the number of dressings applied, and the reduction in the amount of exudates over the wound surface. The results were compared with existing literature on NPWT. (Case 1 & 2).

The authors conducted a prospective cohort study over a duration of 2 years.

Sample size

Based on the study by Cilindro De Souza et al. [8], which reported satisfactory NPWT outcomes in 87.2% of cases, the sample size was calculated using 10 % margin of error and 5 % level of significance.

24 patients were included in the final analysis.

Inclusion criteria

Patients of all age groups with highly exudative wounds not amenable to primary surgical closure were included. These included:

- Traumatic wounds

- Open fractures

- Fasciotomy wounds

- Chronic non-healing and infected wounds

- Diabetic foot amputations

- Pressure ulcers.

Exclusion criteria

Patients were excluded if they had any of the following:

- Malignant wounds

- Known allergy to adhesive materials

- Exposed vital structures (blood vessels, nerves, or organs)

- Bleeding disorders.

Ethical clearance

Ethical clearance from the institutional ethical committee was taken IEC number-19/14/17/IEC/2012 (Dated-September 14, 2019) Informed consent from all patients was taken.

Materials used

Negative pressure source: A portable suction machine equipped with a pressure control valve, calibrated to deliver 100–120 mmHg of negative pressure.

Canister: Integrated with the suction unit for collection and quantification of wound exudates.

Electric timer switch: Manually programmable to deliver intermittent suction cycles – 5 min “on” and 3 min “off”.

Foam dressing: Pre-sterilized, biocompatible, hydrophobic polyurethane foam with pore sizes of 400–600 microns, ensuring uniform suction and optimal tissue granulation.

Adhesive dressing material: Transparent occlusive films are used to create an airtight seal over the foam.

Connecting tubes: Sterile tubing used to connect the dressing to the suction unit.

Methodology

Eligible patients were enrolled after obtaining informed consent. Each wound was thoroughly evaluated and documented regarding:

- Wound dimensions

- Amount of granulation tissue

- Presence of necrosis or exudates

- Signs of infection or inflammation.

Wound area measurement

The longest dimension of the wound was measured using a measuring tape. A calibrated photograph was taken and uploaded into a mobile wound measurement application. It was used to delineate wound boundaries and automatically calculate the wound area based on a reference scale.

Dressing application procedure

The wound was debrided to remove necrotic tissue.

The polyurethane foam was cut to size and placed on the wound bed.

A sterile connector was inserted and connected to the drainage tubing.

The entire dressing was sealed with an adhesive occlusive film.

A 2 cm opening was made in the film to accommodate the suction tube.

The tube was connected to the suction machine, which was in turn attached to a programmable timer.

The suction pressure was set between 100 and 120 mmHg, and the timer configured for intermittent cycles.

Dressings were changed every 3rd day or earlier based on clinical assessment. Exudate volume and quality of granulation tissue were recorded during each dressing change. The wound was re-evaluated at each follow-up for progression toward healing.

Termination of SNPWD

SNPWD was discontinued once the wound exhibited:

Bright red granulation tissue covering >85% of the wound surface

Absence of infection or necrosis

Readiness for secondary closure, split-thickness skin grafting, or flap coverage

Final wound area, total duration of SNPWD application, and number of dressing changes were documented for outcome comparison with data from existing NPWT literature.

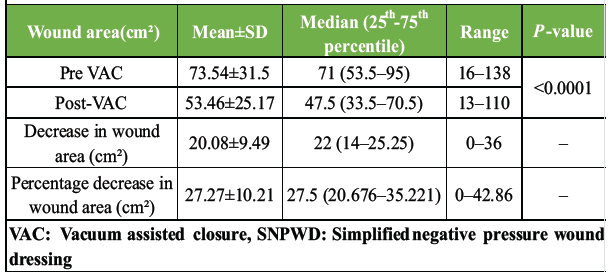

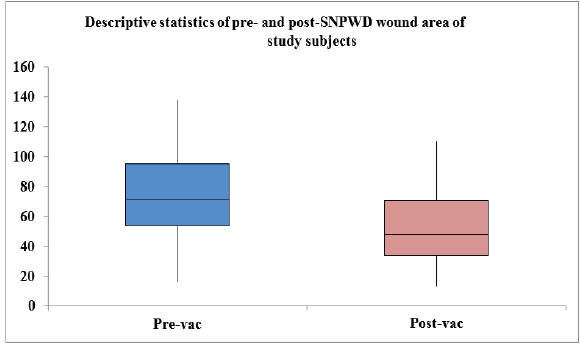

A total of 24 patients were treated by SNPWD between October 2019 and August 2021. All the patients were hospitalized, as this was essentially an in-patient study. No patient was lost to follow-up or withdrew from the study. There were 20 males (83.3%) and only 4 females (16.7%) in the study group. The age of study subjects ranged from 17 to 80 years, with the mean age being 41.58 years. Out of the 24 patients, 11 cases (46%) had acute traumatic wounds that occurred immediately after trauma and were usually associated with underlying fractures. Six cases (25%) had chronic wounds, which were formed either due to prolonged hospital stay (e.g., Bed sores) or due to failure of previous wounds to heal. Seven cases (29%) had post-operative wounds. The amount of healthy granulation tissue after every dressing was assessed by a single observer in terms of gross appearance of the ulcer till it covered more than 85% of the wound surface area. All the wounds were covered by healthy granulation tissue post-SNPWD. The size of the wound pre-SNPWD ranged from 16 cm² to 138 cm², the mean size being 73.5 cm². Post-SNPWD size of wound ranged from 13 cm² to 110 cm², the mean reduction being 20 cm² (27.2 % decrease in wound surface area), as shown in Table 1 and Fig. 1.

Figure 1: Pre- and post-simplified negative pressure wound dressing wound surface area (in cm²) of study subjects.

Table 1: Statistics showing wound surface area pre- and post-SNPWD (in cm²)

In our study, the mean duration of SNPWD application was 16.5 days, i.e., the time taken for the wound to be ready for surgical closure.

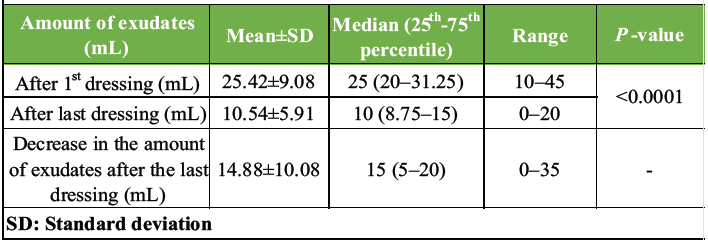

The total number of SNPWD dressings applied per subject ranged between 3 and 9, depending on the size of the wound. The mean number of dressings applied per-subject was 5.3. As shown in Table 2, the amount of exudates collected after every dressing was measured in the canister of the suction machine. After the first dressing, the amount of exudates ranged between 10 and 45 mL, the mean amount being 25.4 mL. After the last dressing, the mean amount of exudates collected was 10.5 mL, which is 58% decrease in the amount of exudates post-SNPWD.

Table 2: Descriptive statistics of the amount of exudates (mL) of study subjects

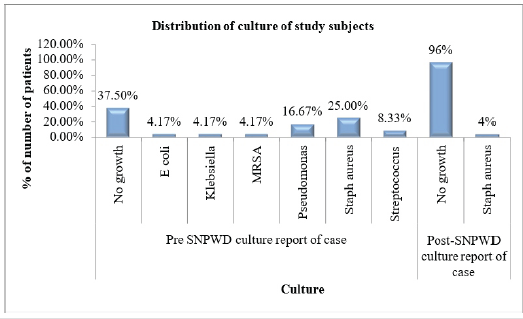

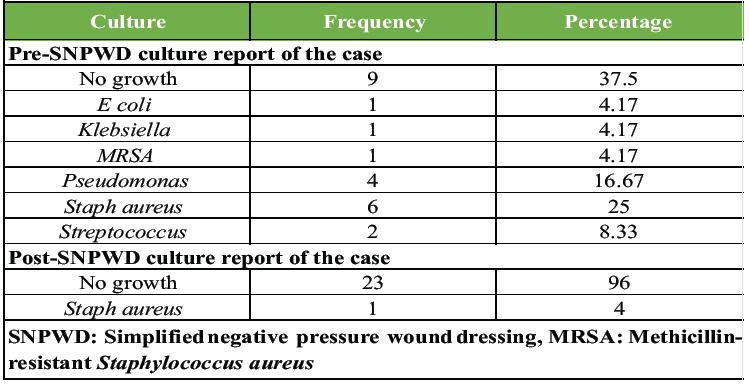

The swab for bacterial culture taken before applying the first SNPWD was positive for Staphylococcus aureus in 6 cases (25%), which was found to be the commonest pathogen, followed by Pseudomonas in 4 cases (17%). Nine cases (37.5%) had a sterile report before the first dressing itself. Post-SNPWD, almost all the patients had a sterile culture sensitivity report (Table 3 and Fig. 2).

Table 3: Distribution of culture report of cases (pre- and post-SNPWD)

Figure 2: Distribution of culture report of cases (pre- and post-simplified negative pressure wound dressing).

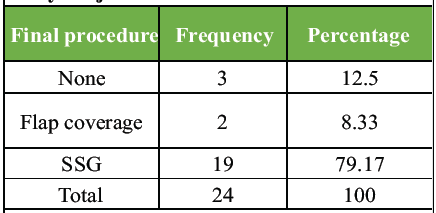

After the final dressing, 3 patients (12.5%) recovered completely and did not require any surgical procedure. In the rest 21 patients, healing by tertiary intention was carried out. Nineteen patients (79.2%) were subjected to SSG (split skin grafting), while 2 patients (8.3%) received flap coverage (Table 4).

Table 4: Distribution of the final procedure of study subjects.

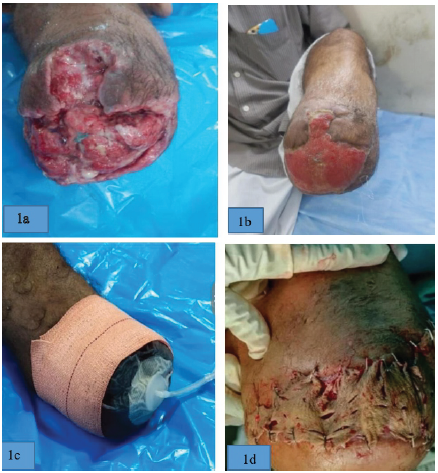

Case of a 49-year-old male with infected below knee amputation stump

Case 1: Illustration (1a) and (1b) showing the pre- and post-SNPWD condition of Wound. Illustration (1c) shows application of SNPWD over wound surface and (1d) showing wound after split skin graft. Case of crush injury right foot with exposed tendons on foot dorsum.

Case 2: Illustration (a) shows pre SNPWD wound condition Illustration (b) shows SNPWD application over wound. Illustration (c) shows post-SNPWD wound condition (considerable decrease in wound surface area). Illustration (d) shows wound condition after 3 months.

NPWT was first described by Chariker et al. [9], in 1989 as an experimental technique for treating incisional and subcutaneous fistulas. Fleischmann et al. [10], in 1993, initiated the use of polyurethane sponge for NPWT. Till date, most of the commercial NPWT options continue to deploy this open-pore polyurethane foam over the wound surface. Argenta et al. [6], used NPWT in his basic animal studies to increase the rate of wound healing. He concluded that blood flow over the wound surface became 4 times when 125 mm Hg sub-atmospheric pressure was applied and tissue bacterial counts also significantly decreased after 4 days of NPWT application. The negative pressure over the wound surface in early studies was achieved by a wall suction or surgical vacuum bottles. However, both these techniques were primitive and had a lot of problems in terms of delivery, control, and maintenance of the required negative pressure over the wound surface, as described by Banwell et al [11]. A study was conducted by Moues et al.,[12] in 2005 on the use of NPWT in the management of acute, traumatic, infected, and chronic full-thickness wounds. They concluded that although NPWT had a significantly high material cost but it was compensated by the fact that it required lesser number of dressings as well as time for the wounds to be ready for surgical closure.

NPWT is thought to promote wound healing by four primary mechanisms [13,14,15,16]:

- Macro-deformation: It is simply induced wound shrinkage when suction is applied to the foam, causing it to shrink in size.

- Micro-deformation: The wound surface deformation at a microscopic level also stretches the cells, enhancing cell division and proliferation.

- Fluid removal: By removing extracellular fluid, the compression forces acting on the microvasculature allow increased blood flow and perfusion of the tissue.

- Alteration of wound environment: It helps in maintaining a warm, sterile, and moist environment over the wound surface by minimizing water evaporation from the wound surface.

All these primary mechanisms lead to the following secondary effects [17,18,19,20,21].

- Angiogenesis and granulation tissue formation

- Upregulation of neurotransmitters

- Cellular infiltration

- Modulation of inflammation

- Decreased bacterial bio-burden over the wound surface

Clinical experience using NPWT VAC

Many studies have established NPWT as a highly efficacious modality in the management of Gustilo Anderson grade 3B injuries [22], extensive degloving injuries [23], grafting or reconstructive surgeries [24], and infected sternotomy wounds [25]. Smith et al, [26] in 1997 suggested to use NPWT as a treatment of choice to do temporary abdominal closure for open abdomen management. The use of NPWT has also been described in the management of the graft donor sites, such as the radial forearm [27]. NPWT has also been used in conjunction with split-thickness skin grafts in the management of burns [28]. Numerous studies have described the successful use of NPWT in the management of chronic and non-healing wounds, such as below-knee amputation sores, bed sores [29], diabetic foot [30], and leg ulcers. The use of NPWT in developing countries [31] like India is limited due to difficulties of terrain, equipment availability, and the high cost of material. In this study, different components of NPWT were assembled and integrated to be used as a SNPWD. The components of SNPWD include a negative pressure source, an electric timer switch, and dressing materials. The study is a prospective observational study in which 24 patients of age between 17 years and 80 years were included in the study, with a mean age being 41.58 ± 14.7 years. This was in accordance with other studies in the literature having younger affected population conducted by Stannard et al. [33] in 44 patients with a mean age of 41 years and Llanos et al, [34] in 60 patients with a mean age of 34 years. The study subjects constituted 20 males (83.3%) and 4 females (16.7%). This male predominance was also seen in studies of Amarnath et al, [7] and Stannard et al [33] which had 82% and 73% male population, respectively. The significantly higher male predominance can be attributed to the fact that most of the wounds managed by SNPWD were caused primarily by road traffic accidents, which occurred when the patients were driving two-wheelers or three-wheelers and in the Indian population, most of the two-wheeler and three-wheeler drivers are males. The most common sites of wounds was right and left knee, followed by the ankle and lower back. Etiologically, the most common type of wounds were acute traumatic wounds (46%), followed by post-operative (29%) and chronic non-healing wounds (25%). The study of Atay et al. [35] also had acute traumatic wounds as the most common type (66%). The decrease in mean wound surface area after SNPWD application in our study was 27.2% (the mean pre-SNPWD wound surface area being 73.5 cm²), which was statistically significant (P < 0.001). This reduction in wound surface area was comparable to studies done by Atay et al. [35] and Jones et al. [36] who achieved a mean reduction in wound surface area of 28.8% and 29% for pre-VAC wound size of 94.7 cm² and 95.65 cm² respectively, using commercially available NPWT options.

SNPWD was applied till the time the wound was ready for definitive closure, that is, bright red granulation tissue covered more than 85% of the wound surface area. All the cases developed healthy granulation tissue in some time. The mean duration of SNPWD application, that is, the time taken for development of healthy granulation tissue, ranged from 8 to 27 days, the mean duration being 16.5 days. The mean number of dressings applied per patient was 5.3. Similar results were obtained in a study of Kilic et al., [37] who achieved 30% reduction in mean wound size after applying VAC to 17 patients for average 16 days. Demir et al, [38] also demonstrated that mean duration of wound healing was 12.4 days and mean reduction in wound surface area after applying VAC to 50 cases was 23%. The mean amount of exudates collected in the canister decreased by 58% (from 25.4 mL pre-SNPWD to 10.5 ml post-SNPWD). The decrease in the amount of discharge was also reported in a study of Ali et al. [39], in which there was complete cessation of amount of discharge in 60% patients after week 2 and reached to 96% till week 7. The post-SNWPD culture report of wounds was sterile in 96% of cases, as compared to only 37.5% sterile culture reports before applying SNPWD. The most common organism cultured from wounds before SNPWD application was Staphylococcus aureus (25%), followed by Pseudomonas (16.67%). However, the increase in the number of sterile culture reports may also be due to the fact that wound debridement was being done after every dressing change and most of the patients were being given intravenous antibiotics during the course of SNPWD. In our study, 12.5% of the wounds closed by secondary healing itself and did not require any other surgery for healing, while 87.5% of wounds healed by tertiary healing and required either SSG or flap surgery for closure. This is comparable to the study of Atay et al. [35], in which 18.75% of wounds closed by secondary healing. The cost of the suction machine and timer switch used to provide intermittent suction was ₹4,000 and ₹1,400, respectively. The per dressing cost of SNPWD was ₹600. In comparison, the cost per dressing of VAC is ₹7,000 while the machine costs approximately ₹2.5 lakh. Thus, not only SNPWD per dressing cost is 10 times lesser as compared to VAC dressing, but the markedly lower cost of equipment makes it a potential alternative to VAC dressing in low-resource settings.

The adverse effects of SNPWD were minor and rare. These included:

Pain at the dressing site, especially while removing the dressing was observed in some patients. Skin maceration was seen in 2 patients, who were subjected to a prolonged duration of SNPWDs. Fever, documented at 101°F, occurred in 1 patient after the application of SNPWD. However, there were only 2 episodes that got relieved after giving a suitable dose of antipyretic. Furthermore, a potential disadvantage of using SNPWD over VAC was that the lack of an automated pressure-sensing system made it difficult to address the minor air leaks. This resulted in more frequent dressing changes in some patients.

The findings of our study demonstrate that the indigenously developed SNPWD is a clinically effective and economically viable alternative to commercially available NPWT systems. SNPWD showed comparable outcomes in terms of granulation tissue formation, wound surface area reduction, duration of healing, and exudate management – key parameters in evaluating wound healing efficacy. In addition to its therapeutic effectiveness, SNPWD offers significant advantages in terms of affordability, ease of use, and patient compliance. It’s low cost – approximately 10 times less than that of standard VAC systems – makes it especially suitable for use in resource-limited settings. Moreover, its portability and simple mechanism allow for potential outpatient or even home-based care, thereby reducing hospital admissions and easing the burden on already strained healthcare facilities. Given these benefits, SNPWD presents a safe, cost-effective, and non-inferior alternative for managing complex wounds, particularly in low- and middle-income countries. Its use allows the decision to initiate NPWT to be guided primarily by clinical need rather than cost constraints.

An indigenous;y developed simplified negative pressure wound dressing (SNPWD) provides a practical, safe and cost effective alternative to commercial NPWT systems. It promotes rapid granulation tissue formation, reduces wound size, decreases exudate burden and improves wound sterility with fewer dressing changes. SNPWD can be easily adopted in routine clinical practice, particularly in resource constrained settings, to achieve outcomes comparable to standard NPWT while significantly reducing treatment costs.

References

- 1. Bennett NT, Schultz GS. Growth factors and wound healing: Biochemical properties of growth factors and their receptors. Am J Surg 1995;165:728-37. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 2. Lawrence WT. Physiology of the acute wound. Clin Plast Surg 1998;25:321-40. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 3. Ward J, Holden J, Grob M, Soldin M. Management of wounds in the community: Five principles. Br J Community Nurs 2019;24:S20-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 4. Argenta LC, Morykwas MJ. Vacuum-assisted closure: A new method for wound control and treatment: Clinical experience. Ann Plast Surg 1997;38:563-76; discussion 577. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 5. Caudle RJ, Stern PJ. Severe open fractures of the tibia. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1987;69:801-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 6. Malmsjo M, Ingemansson R, Martin R, Huddleston E. Wound edge microvascular blood flow: Effects of negative pressure wound therapy using gauze or polyurethane foam. Ann Plast Surg 2009;63:676-81. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 7. Amarnath S, Reddy MR, Rao CH, Surath HV. Timer switch to convert suction apparatus for negative pressure wound therapy application. Indian J Plast Surg 2014;47:412-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 8. Cilindro de Souza S, Henrique Briglia C, Miranda Cavazzani R. A simplified vacuum dressing system. Wounds 2016;28:48-56. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 9. Chariker ME, Jeter KF, Tintle TE, Bottsword JE. Effective management of incisional and cutaneous fistulae with closed suction wound drainage. Contemp Surg 1989;34:59-63. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 10. Fleischmann W, Strecker W, Bombelli M, Kinzl L. Vacuum sealing as treatment of soft tissue damage in open fractures. Unfallchirurg 1993;96:488-92. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 11. Banwell P, Withey S, Holten I. The use of negative pressure to promote healing. Br J Plast Surg 1998;51:79. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 12. Moues CM, van den Bemd GJ, Meerding WJ, Hovius SE. An economic evaluation of the use of TNP on full-thickness wounds. J Wound Care 2005;14:224-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 13. Scherer SS, Pietramaggiori G, Mathews JC, Prsa MJ, Huang S, Orgill DP. The mechanism of action of the vacuum-assisted closure device. Plast Reconstr Surg 2008;122:786-97. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 14. Orgill DP, Bayer LR. Negative pressure wound therapy: Past, present and future. Int Wound J 2013;10 Suppl 1:15-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 15. Lancerotto L, Bayer LR, Orgill DP. Mechanisms of action of microdeformational wound therapy. Semin Cell Dev Biol 2012;23:987-92. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 16. Morykwas MJ, Simpson J, Punger K, Argenta A, Kremers L, Argenta J. Vacuum-assisted closure: State of basic research and physiologic foundation. Plast Reconstr Surg 2006;117:121S-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 17. Younan G, Ogawa R, Ramirez M, Helm D, Dastouri P, Orgill DP. Analysis of nerve and neuropeptide patterns in vacuum-assisted closure-treated diabetic murine wounds. Plast Reconstr Surg 2010;126:87-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 18. Erba P, Ogawa R, Ackermann M, Adini A, Miele LF, Dastouri P, et al. Angiogenesis in wounds treated by microdeformational wound therapy. Ann Surg 2011;253:402-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 19. Ma Z, Shou K, Li Z, Jian C, Qi B, Yu A. Negative pressure wound therapy promotes vessel destabilization and maturation at various stages of wound healing and thus influences wound prognosis. Exp Ther Med 2016;11:1307-17. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 20. McNulty AK, Schmidt M, Feeley T, Kieswetter K. Effects of negative pressure wound therapy on fibroblast viability, chemotactic signaling, and proliferation in a provisional wound (fibrin) matrix. Wound Repair Regen 2007;15:838-46. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 21. Mouës CM, Vos MC, van den Bemd GJ, Stijnen T, Hovius SE. Bacterial load in relation to vacuum-assisted closure wound therapy: A prospective randomized trial. Wound Repair Regen 2004;12:11-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 22. Bauer P, Schmidt G, Partecke BD. Possibilities of preliminary treatment of infected soft tissue defects by vacuum sealing and PVA foam. Handchir Mikrochir Plast Chir 1998;30:20-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 23. DeFranzo AJ, Marks MW, Argenta LC, Genecov DG. Vacuum-assisted closure for the treatment of degloving injuries. Plast Reconstr Surg 1999;104:2145-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 24. Avery C, Pereira J, Moody A, Whitworth I. Clinical experience with the negative pressure wound dressing. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2000;38:343-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 25. Tang AT, Okri SK, Haw MP. Vacuum-assisted closure to treat deep sternal wound infection following cardiac surgery. J Wound Care 2000;9:229-30. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 26. Smith LA, Barker DE, Chase CW, Somberg LB, Brock WB, Burns RP. Vacuum pack technique of temporary abdominal closure: A four-year experience. Am Surg 1997;63:1102-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 27. Avery C, Pereira J, Moody A, Gargiulo M, Whitworth I. Negative pressure wound dressing of the radial forearm donor site. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2000;29:198-200. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 28. Teng SC. Use of negative pressure wound therapy in burn patients. Int Wound J 2016;13 Suppl 3:15-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 29. Deva AK, Siu C, Nettle WJ. Vacuum-assisted closure of a sacral pressure sore. J Wound Care 1997;6:311-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 30. Nather A, Chionh SB, Han AY, Chan PP, Nambiar A. Effectiveness of vacuum-assisted closure (VAC) therapy in the healing of chronic diabetic foot ulcers. Ann Acad Med Singap 2010;39:353-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 31. Yadav S, Rawal G, Baxi M. Vacuum assisted closure technique: A short review. Pan Afr Med J 2017;28:246. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 32. Stannard JP, Robinson JT, Anderson ER, McGwin G Jr., Volgas DA, Alonso JE. Negative pressure wound therapy to treat hematomas and surgical incisions following high-energy trauma. J Trauma 2006;60:1301-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 33. Llanos S, Danilla S, Barraza C, Armijo E, Piñeros JL, Quintas M, et al. Effectiveness of negative pressure closure in the integration of split thickness skin grafts: A randomized, double-masked, controlled trial. Ann Surg 2006;244:700-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 34. Atay T, Burc H, Baykal YB, Kirdemir V. Results of vacuum assisted wound closure application. Indian J Surg 2013;75:302-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 35. Jones DA, Neves Filho WV, Guimarães JS, Castro DA, Ferracini AM. The use of negative pressure wound therapy in the treatment of infected wounds. Case studies. Rev Bras Ortop 2016;51:646-51. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 36. Kilic A, Ozkaya U, Sökücü S, Basilgan S, Kabukçuoğlu Y. Cerrahi alanda gelişen enfeksiyonlarin tedavisinde vakum yardimli örtüm sistemi uygulamalarimiz [Use of vacuum-assisted closure in the topical treatment of surgical site infections]. Acta Orthop Traumatol Turc 2009;43:336-42. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 37. Demir A, Demirtaş Y, Ciftci M, Öztürk N, Karacalar A. Topical negative pressure applications. Türk Plast Rekonstr Estcer Derg 2006;14:171-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 38. Ali Z, Anjum A, Khurshid L, Ahad H, Maajid S, Dhar SA. Evaluation of low-cost custom made VAC therapy compared with conventional wound dressings in the treatment of non-healing lower limb ulcers in lower socio-economic group patients of Kashmir valley. J Orthop Surg Res 2015;10:183 [Google Scholar] [PubMed]