The main purpose of this article is to spread awareness regarding primary sternal tuberculosis, which can present as a vague anterior chest wall swelling of an extended duration which may remain unnoticed or neglected due to the lack of any signs and symptoms and the main treatment protocol is the administration of anti tubercular drugs and surgical management is rarely necessary.

Dr. Adnan Asif, Department of Orthopaedic, K B Bhabha Municipal General Hospital, Mumbai, Maharashtra, India. E-mail: adnan.asif1092@gmail.com

Introduction:Extrapulmonary tuberculosis (TB) mainly involves the spine and weight-bearing joints and sternal TB accounts for only 1% of musculoskeletal TB cases. Diagnosis and management of sternal TB propose a challenge at times due to the rarity and unfamiliarity of the presentations.

Case Report:We present two cases of TB of sternum that presented to our institute. The first patient was a 52-year-old male with 2 months history of swelling over the chest wall and the second was a 19-year-old female who presented with swelling for 1 week. Both patients were managed with anti-tubercular drugs for 12 months and had complete resolution of the disease. The patients were not on any medication prior to their presentations.

Conclusion: Isolated sternal TB is an exceedingly rare form of TB which usually presents as a chest wall swelling without any constitutional symptoms. Antitubercular medication is the mainstay of treatment and surgical intervention is reserved for only few cases.

Keywords:Antitubercular treatment, sternum, tuberculosis.

Tuberculosis (TB) is a major international public health issue with associated high morbidity and mortality if not treated adequately, with an estimated global case fatality rate of around 13% [1], especially in less developed countries like India. In India, pulmonary TB accounts for 80% to 85% of cases whereas extrapulmonary TB accounts for 15–20% with musculoskeletal involvement being seen in just 1–3% of these cases only [2]. Approximately 60–80% of skeletal TB cases involve the spine or weight-bearing joints, while the sternum is involved in approximately just 1% of the cases [3, 4].

TB osteomyelitis of the sternum is an exceedingly rare form of extrapulmonary TB and therefore the literature concerning it is sparse as only a few cases of primary sternal TB have been reported in the literature [5, 6]. Tuberculous involvement of the sternum is rare even in countries where TB is highly prevalent and primary sternal osteomyelitis accounts for about 0.3% of all kinds of osteomyelitis [7].

Diagnosis might be delayed due to the unusual presentation, unfamiliarity, lack of awareness, and the rare occurrence of sternal TB. We present two cases of sternal tubercular osteomyelitis that reported to our institute and had a complete recovery.

Case 1

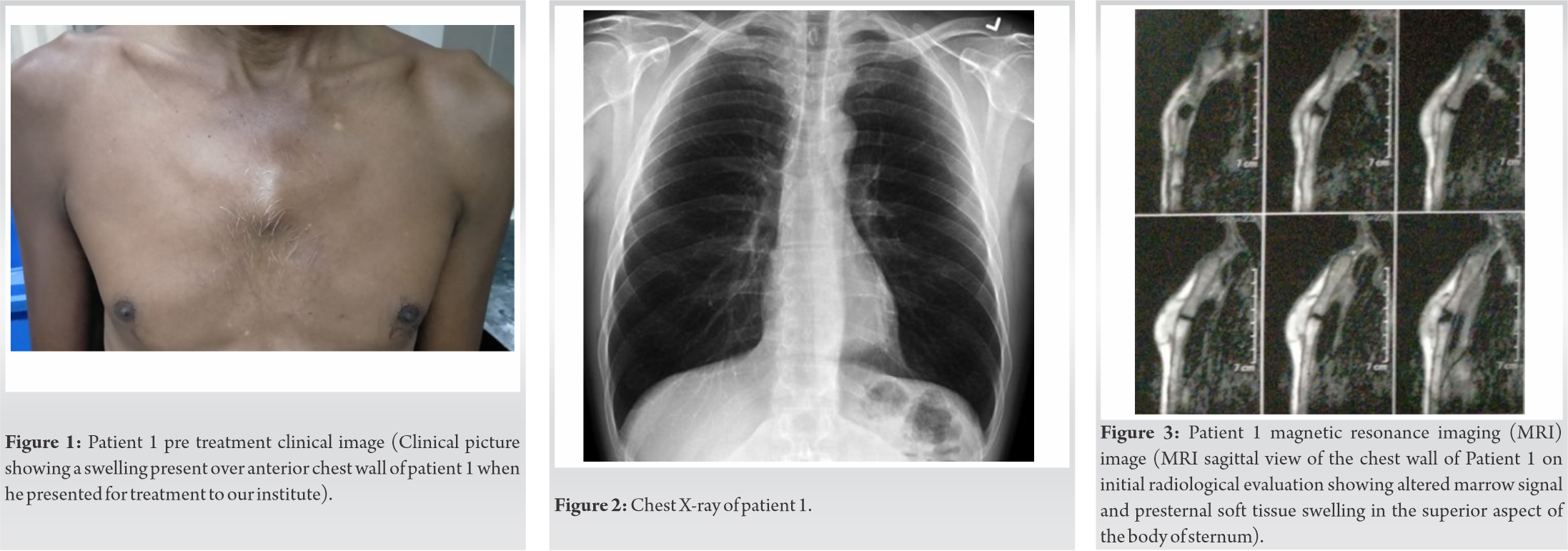

A 52-year-old male presented with a gradually progressive swelling over the anterior chest wall for the past 2 months (Fig. 1). Swelling was present over the sternum in the midline and was insidious in onset and gradually increased in size to its present state, associated with pain which was mild in intensity, non-radiating, and relieved on analgesics.

He is a service employee and belongs to the lower middle socioeconomic class as per modified Kuppuswamy scale. He had received a 1 week course of empirical antibiotics before presenting to us. He had no significant history and was immunocompetent. He had no history of weight loss, loss of appetite, night sweats, malaise, or fatigue. He did not report any history of fever or cough and there was no history of contact with tuberculous infection or any history in his family. His Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) vaccination status was unconfirmed. There was no history of trauma to the anterior chest wall or any surgery in the vicinity.

He was of average build, afebrile, with normal vital parameters on presentation. He was a known hypertensive on oral medications for the same. There was a solitary visible swelling over the sternum that was 5*2 cms in measurement, firm in consistency, tender on palpation, without local rise of temperature, non-fluctuant, and non mobile. The overlying skin was not stretched or shiny, without any discoloration and surrounding area appeared normal. There was no sinus or fistula formation and there were no other significant findings. There was no cervical lymphadenopathy. Chest, abdomen, and neurological assessment were essentially normal.

Initial laboratory findings showed a Hb of 9.6 gm%, TLC of 7200 and an erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) of 50 mm and C-reactive protein (CRP) of 24 mg/L. All other biochemical investigations (liver function, renal function, and blood glucose levels) were within normal limits. Serology for HIV and HBsAg was nonreactive.

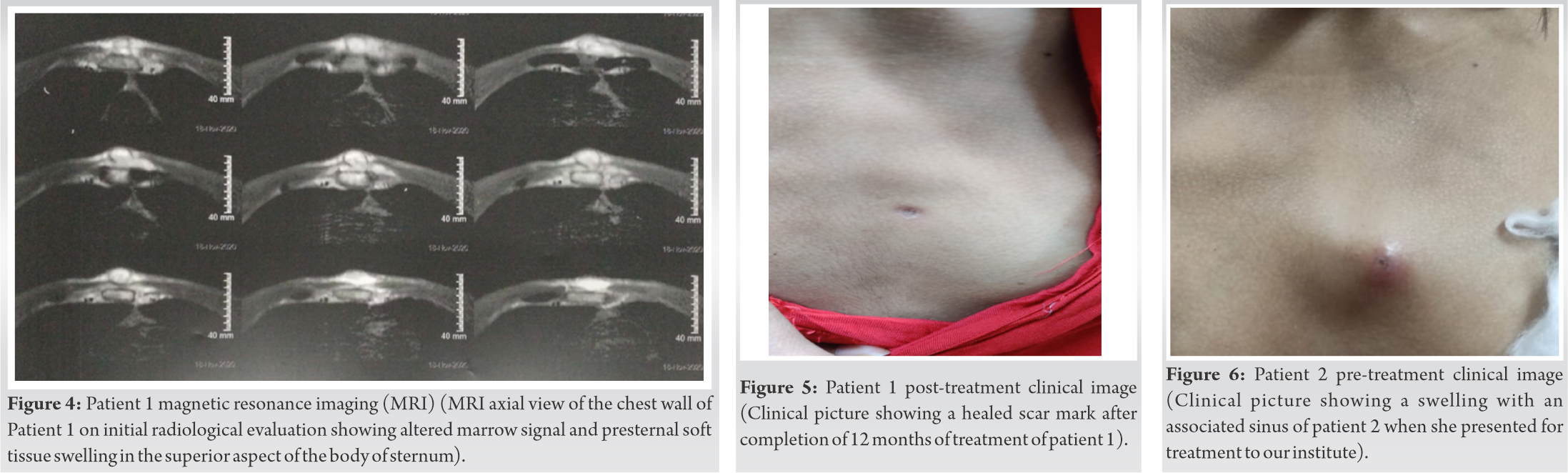

Chest Xray (Fig. 2) was normal and computed tomography (CT) showed an erosion of the anterior cortex of the superior aspect of the sternum with surrounding presternal soft tissue swelling which was correlated by a concomitant magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) which showed altered marrow signal in the superior part of the sternum (Fig. 3, 4). No pathological findings in the pulmonary parenchyma, pleura, and lymph nodes were detected.

A fine-needle aspiration was performed for the swelling and sent for analysis, which showed no acid-fast bacilli with Ziehl-Neelsen (ZN) stain and no growth on culture after 72 h.

GeneXpert MTB test showed the presence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis which was sensitive to Rifampicin.

He was started on daily dose anti-tubercular therapy (ATT) with intensive phase consisting of four drugs, which were isoniazid, rifampicin, pyrazinamide, and ethambutol for 2 months and then followed by continuation phase consisting of isoniazid, rifampicin, and ethambutol. He was on regular follow-up and completed 12 months of ATT treatment and has attained complete clinical and radiological recovery (Fig. 5).

Case 2

A 19-year-old female presented with a swelling over the anterior chest wall since 1 week (Fig. 6). Swelling was present over the sternum in the midline and was insidious in onset and gradually increased in size to its present state, associated with pain which was mild in intensity, non-radiating, and not relieved on analgesics.

She had no significant past history and was immunocompetent. She had no history of weight loss, loss of appetite, night sweats, malaise, or fatigue. She did not report any history of fever or cough. There was no history of contact with tuberculous infection or any history in her family. She had received BCG vaccination at birth. There was no history of trauma to anterior chest wall or any surgery in the vicinity.

She was of moderate build, afebrile, with normal vital parameters at presentation. There was a solitary visible swelling over the sternum that was 3*2 cms in measurement, firm in consistency, tender on palpation, without a local rise of temperature, nonfluctuant, and non mobile. The overlying skin was stretched and shiny with the presence of a sinus with surrounding induration and redness. There was no active discharge from the sinus. Systemic examinations were essentially normal.

Initial laboratory findings showed a Hb of 10.1gm% and TLC, ESR and CRP were all within normal limits. All other biochemical investigations (liver function, renal function, and blood glucose levels) were within normal limits. Serology for HIV and HBsAg was nonreactive.

Chest X-ray (Fig. 7) was normal and Ultrasound of the swelling showed a breach in the continuity of cortex of sternum with a hypoechoic collection of 1*0.6*2 cms overlying the defect.

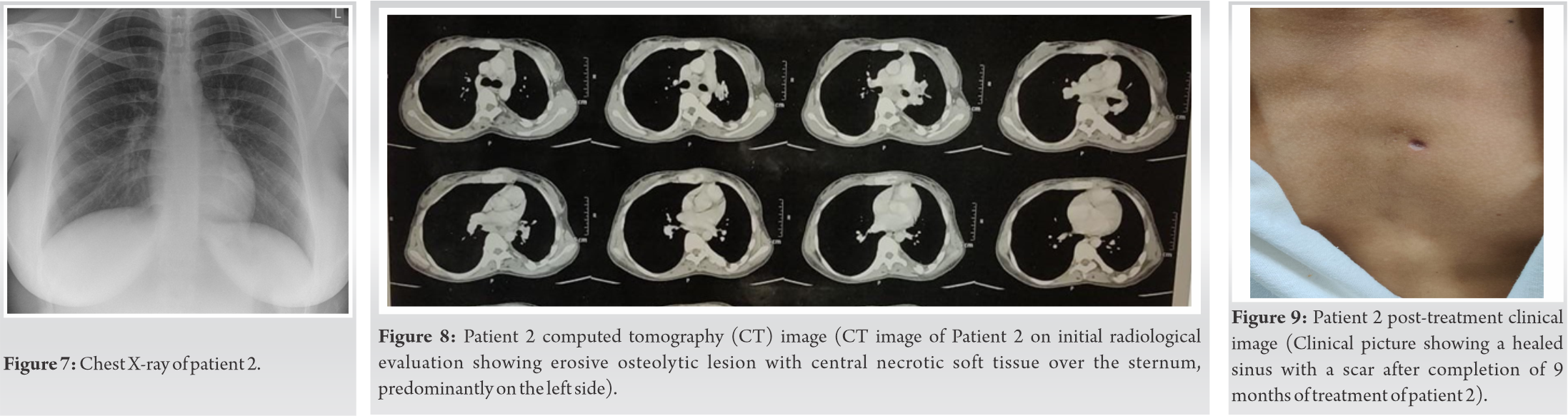

CT showed erosive osteolytic changes with central necrotic soft tissue involving the sternum and anterior chest wall of size 24*20 mm along with multiple enlarged and necrotic lymph nodes (Fig. 8).

A fine-needle aspiration was performed for the swelling and sent for analysis, which showed no acid-fast bacilli with ZN stain and no growth on culture after 72 h.

GeneXpert MTB test showed the presence of M. tuberculosis which was sensitive to Rifampicin. TB-MGIT test confirmed the presence of M. tuberculosis and showed that it was sensitive to all first-line anti-tubercular drugs.

She was started on daily dose ATT with intensive phase consisting of four drugs, which were isoniazid, rifampicin, pyrazinamide, and ethambutol for the first 2 months of therapy. This was followed by the continuation phase of three drugs, isoniazid, rifampicin, and ethambutol. Currently, she is on regular follow-up and has completed 9 months of ATT treatment and her swelling is not present anymore and the sinus has healed (Fig. 9). She does not have any signs or symptoms at present and will be followed up on ATT for a minimum of 12 months duration.

TB of the sternum is a very rare occurrence amongst extrapulmonary TB. Tuli and Sinha [8] reported a series of 980 patients with osteoarticular TB in which 14 (1.4%) had sternal lesions. In a more recent study by Davies et al. [9], only two cases of TB of the sternum were found in the series of 4000 cases.

A high degree of suspicion is required to overcome the diagnostic dilemma, especially if there is no associated pulmonary TB. Symptoms usually include soft tissue swelling over the sternum, which is the most common symptom and mostly associated with dull aching pain. Swelling is associated with erythema, warmth and tenderness and enlarged regional lymph nodes and might be associated with a draining abscess or sinus. Bone deformity or fracture may be present in advanced stages. Constitutional symptoms such as malaise, fever, night sweats, or weight loss are less commonly seen.

Sternal osteomyelitis mainly occurs as part of hematogenous or lymphatic dissemination of the disease from other sites or the reactivation of latent loci formed during the dissemination of primary TB [10]. The direct extension from hilar lymph nodes or infection of retrosternal lymph nodes that erode into the sternum over time can also be another mechanism.

Inflammatory markers such as ESR, CRP and total white blood cell count (TLC) are mostly elevated but are neither specific nor entirely reliable. Chest radiographs are normal in approximately 70% of these cases, and approximately 40% have evidence of TB in sites other than the sternum, with the lymphatic system being the most common [11].

Clinical symptoms usually precede radiological changes, which are varied depending on the progression of osteomyelitis. Plain radiographs are often normal but radiographic techniques such as CT and MRI are more valuable for localization and detection of bone destruction and soft tissue abnormalities. Radiographic findings can include osteoporosis, osteopenia, bone lysis, sclerosis, periostitis, or pathological fracture in advanced disease. CT scans can be used to determine anatomical localization, soft tissue abnormalities, and osseous destruction. MRI delineates abscesses better in the soft tissues, and highlights bone marrow involvement and is therefore used for early detection of sternal TB due to the high contrast resolution of MRI.

The differential diagnosis of chest wall masses with or without discharging sinuses has to be considered which can include pyogenic infections, malignancy, granulomatous lesions, or fungal infections. In sternal TB, the cartilage is first destroyed peripherally with the preservation of joint space for a long period of time. Thus, it commonly presents with an indolent, painless course without constitutional symptoms. On the other hand, patients with pyogenic sternal infections will have a fulminant clinical course as they can cause cartilage destruction by the release of proteolytic enzymes, and they present with prominent constitutional symptoms.

A needle aspiration or excisional biopsy is mandatory for histopathological and microbiological diagnosis of sternal osteomyelitis because radiological findings cannot differentiate the cause of osteomyelitis, and sometimes the lesions grossly simulate pyogenic abscess or neoplasm [12, 13]. The diagnosis is usually confirmed by finding acid-fast bacilli and positive AFB cultures, and caseous necrosis and granuloma on histopathology. Polymerase chain reaction and GeneXpert nucleic acid probes are now available for more rapid identification of mycobacteria not readily seen by microscope.

Antitubercular drugs are the mainstay of treatment for sternal TB osteomyelitis currently. Although there is no standard guideline to the precise regimen and duration of treatment, extrapulmonary TB is generally treated with a 9–12 months regime of first-line drugs, unless the organisms are known to be resistant to these first-line drugs. Directly observed therapy is strongly recommended to better ensure medication compliance [14]. These regimens consist of combinations of rifampicin, isoniazid, pyrazinamide, and ethambutol for the first two to 4 months as intensive therapy, followed by maintenance therapy with isoniazid and rifampicin for the next 6 months to 1 year. Variations in regimens can be made depending on clinical and radiographic response, side effects, and culture and sensitivity results. Clinical response precedes the radiographic response and usually starts within 2 months of starting the course.

Khan et al. [15]. In their study found that surgical intervention was only necessary in a few cases. In their series, 12 out of 14 patients with TB of the sternum who were initially treated with multi-drug ATT, did not require any surgical interventions. The surgical options are usually not needed for routine cases, but if needed comprise complete drainage, thorough debridement, and sternectomy, with or without requiring a muscle flap, along with multi-drug ATT.

Isolated primary sternal osteomyelitis is a rare form of flat bone TB, despite the high prevalence of TB in endemic countries such as India. It needs a high index of suspicion for appropriate diagnosis. Most cases present with soft tissue swelling or discharging sinus over the sternum. Sternal osteomyelitis mainly occurs as part of hematogenous or lymphatic dissemination of the disease from other sites or the reactivation of latent loci formed during dissemination of primary TB. The possibility of sternal TB should be kept in mind in any patient with a mass, non-healing ulcer, or abscess in the sternal region. Bony destruction can be disclosed easily with radiographic techniques such as CT and MRI, but diagnosis is confirmed by culture or histopathological examination. Antitubercular therapy is the mainstay of treatment and surgical drainage and resection is rarely required. A proper follow-up is necessary to monitor the response to treatment, any drug resistance, and to avoid any complications. Complete recovery can be assessed by clinical wellbeing, resolution of symptoms, and normalization of hematological parameters such as ESR, CRP. Radiological confirmation is rarely required as radiological picture lags behind clinical picture.

The main purpose of this article is to spread awareness regarding primary sternal TB, which can present as a vague anterior chest wall swelling of an extended duration that may remain unnoticed or neglected due to the lack of any signs and symptoms. The main treatment protocol is the administration of anti-tubercular drugs and surgical management is rarely necessary.

References

- 1.Jain A, Chawla S, Kumar M. Sternal tuberculous osteomyelitis: A series of four cases. Int J Community Med Public Health 2017;2:288-92. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shanmugasundaram T. Bone and joint tuberculosis-guidelines for management. Indian J Orthop 2005;39:195-8. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boh JA, Janner D. Mycobacterium tuberculosis sternal osteomyelitis presenting as anterior chest wall mass. Pediatr Infect Dis J 1999;18:1028-9. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Watts HG, Angrles L, Lifesto RM. Current concepts review: Tuberculosis of bones and joints. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1996;78:288-98. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sharma S, Juneja M, Garg A. Primary tubercular osteomyelitis of the sternum. Indian J Pediatr 2005;72:709-10. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Allali N, Dafiri R. Tuberculosis of the sternum. J Radiol 2005;86:655-6. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Saifudheen K, Anoop TM, Mini PN, Ramachandran M, Jabbar PK, Jayaprakash R. Primary tubercular osteomyelitis of the sternum. Int J Infect Dis 2010;14:e164-6. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tuli S, Sinha G. Skeletal tuberculosis “unusual lesions”. Indian J Orthop 1969;3:5-19. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davies PD, Humphries MJ, Byfield SP, Nunn AJ, Darbyshire JH, Citron KM, et al. Bone and joint tuberculosis. A survey of notifications in England and wales. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1984;66:326-30. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kato Y, Horikawa Y, Nishimura Y, Shimoda H, Shigeto E, Ueda K. Sternal tuberculosis in a 9-month-old infant after BCG vaccination. Acta Paediatr 2000;89:1495-7. [Google Scholar]

- 11.McLellan DG, Philips KB, Corbett CE, Bronze MS. Sternal osteomyelitis caused by mycobacterium tuberculosis: Case report and review of the literature. Am J Med Sci 2000;319:250-4. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rizzo V, Salmasi Y, Hunter M, Sidhu P. Delayed diagnosis of chronic postoperative sternal infection: A rare case of sternal tuberculosis. BMJ Case Rep 2018;2018:bcr2017223650. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Calabrò E, Pastorino U. Primary sternal tuberculosis mimicking a lytic bone tumor lesion. Monaldi Arch Chest Dis 2018;88:931. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cohn DL, Catlin BJ, Peterson KL, Judson FN, Sbarbaro JA. A 62-dose, 6-month therapy for pulmonary and extrapulmonary tuberculosis. A twice-weekly, directly observed, and cost-effective regimen. Ann Intern Med 1990;112:407-15. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Khan SA, Varshney MK, Hasan AS, Kumar A, Trikha V. Tuberculosis of the sternum: A clinical study. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2007;89:817-20. [Google Scholar]