If closed radiocapitellar reduction can be achieved in the treatment of neglected Monteggia injuries, ulnar length should be achieved with minimally invasive fixation methods.

Dr. Tahir Ozturk, Department of Orthopaedics and Traumatology, Gaziosmanpasa University, Kaleardi District Muhittin Fisunoglu Street, Ali Sevki EREK Campus, 60030, Tokat, Turkey. E-mail: ozturk.tahir@yahoo.com

IntroductionA pediatric Monteggia injury, when the diagnosis is missed or neglected, is still a challenging problem for the treating orthopedic surgeon. In this case report, we report our treatment method for a neglected Monteggia injury in a 22-month-old child.

Case PresentationA 22-month-old female patient had a history of significant trauma 8 months earlier, but no referral was made to any health institution during this period. The patient presented with swelling in the right elbow and what the family described as an occasional click noise during elbow movements. There was a 1/3 proximal plastic deformation of the ulna on radiographs, with anterior bowing concomitant with an anterior dislocation of the radial head. The patient was evaluated with a diagnosis of neglected type I Monteggia lesion. Conservative follow-up was carried out by applying closed reduction of the radiocapitellar joint under sedation. However, the conservative treatment method failed after 1 week of follow-up. For definitive treatment, closed radiocapitellar reduction and ulnar osteotomy (intramedullary Kirschner wire and oblique Kirschner wires) were applied. At the end of 3 months, the patient had full open range of motion in all directions without pain.

ConclusionThis case report is noteworthy due to the patient’s young age and the ulnar fixation method applied. It also shows that in the presence of ulnar bowing, maintenance of radiocapitellar reduction with only closed reduction without ulnar osteotomy could not be achieved.

KeywordsMonteggia injuries, neglected, pediatric, ulnar osteotomy.

Radial head dislocation with plastic deformation of the ulna specific to children can be a missed injury that is often overlooked in the first radiographic evaluations, because they do not contain a true fracture [1]. There is no clear consensus on a separate classification of this type as Bado type I Monteggia fracture–dislocation or type I equivalent injury [2]. The rate of missed Monteggia injuries is as high as 50%, and the definition of chronic injury is a diagnosis more than 4 weeks after trauma [3]. These missed injuries may cause severe long-term complications, such as persistent pain, limited elbow movement, valgus deformity, late neuropathy, arthrosis, and elbow instability [4].

The accepted primary goal in treating acute Monteggia fracture–dislocations is to correct the ulna length and fix the ulna to ensure the stability of the radial head. Often, no additional radial intervention is applied to reduce the radial head unless necessary [5]. In treating chronic injuries, many treatment strategies focus on reconstructive surgical procedures, especially for reduction of the radial head, by providing the ulna length again [6-12].

This case report aimed to present our treatment method for a neglected Monteggia injury in a 22-month-old child and review the literature in light of this case.

Informed consent was obtained from the relatives of the patient for this case report. A 22-month-old female patient with a history of significant trauma (falling from 50 cm on the right elbow) 8 months earlier was described by the family. Because the patient’s elbow movements were normal and there was no significant pain or deformity in the arm, no application was made to any health institution since the injury. The patient was admitted to our outpatient clinic with complaints of swelling in the elbow and an occasional click noise during elbow movements that were described by the family. On physical examination, inspection identified a prominent mobile swelling in the anterolateral aspect of the elbow, adjacent to the antecubital fossa, compared to the contralateral elbow. This swelling was mobilized to be visible from the outside with pronation and supination maneuvers. There was no pain or tenderness. When pressing on the swelling while performing the supination maneuver in 90° flexion, there was a clicking sound and reduction sensation concomitant to the radial head bone jumping sensation. Elbow joint ranges of motion (ROM) were fully in all directions, and the patient did not have additional neuromotor deficits.

When the elbow was evaluated with contralateral anteroposterior and lateral radiographs (Fig. 1), and computerized tomography (Fig. 2), there was proximal plastic deformation of the 1/3 of the ulna with anterior bowing concomitant with anterior dislocation of the radial head. Therefore, the patient was diagnosed with a neglected type I Monteggia lesion. Due to the possibility of reduction maintenance in the radiocapitellar joint during the examination, conservative treatment (closed reduction and cast) was decided. The patient was provided with the necessary anesthesia preparations and optimal conditions, and fluoroscopic monitoring was used. A longitudinal traction was applied; meanwhile, the radial head was palpated and direct force was applied, resulting in radiocapitellar reduction in the elbow flexion forearm supination position. While the elbow was in the 90° flexion supination position, complete reduction of the radiocapitellar joint was checked with fluoroscopy, and the patient was immobilized with an above-elbow cast (Fig. 3). When the follow-up (1st week) examination revealed that the radial head was dislocated again (Fig. 4), we decided to correct the patient’s ulnar length and bowing.

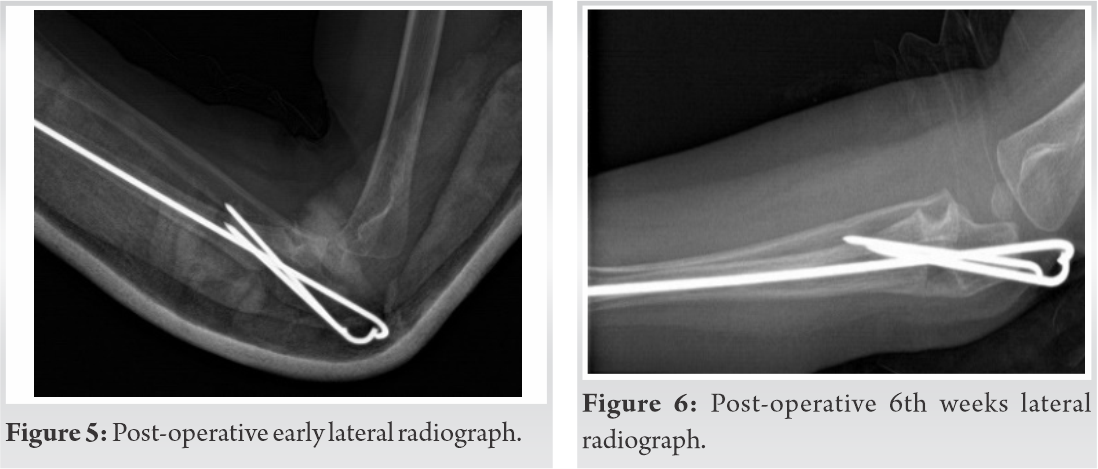

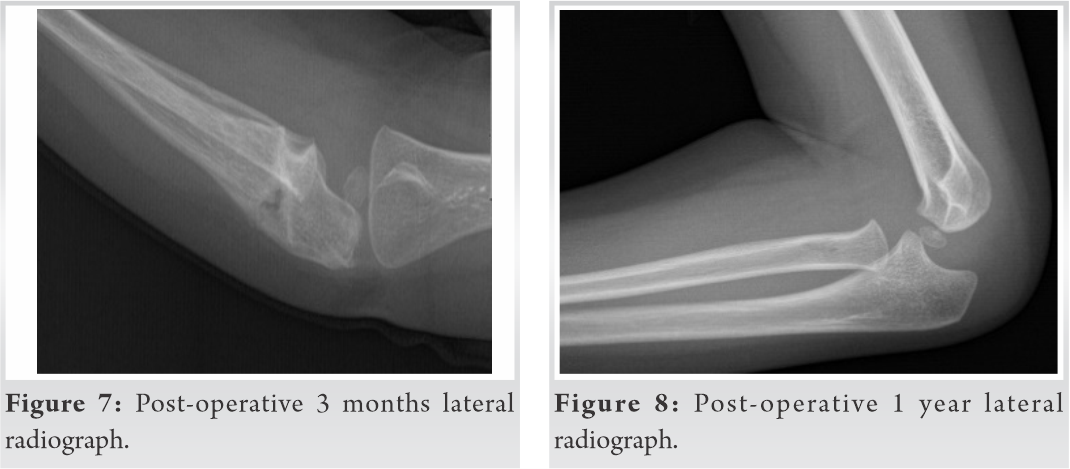

The patient, who did not develop post-operative neuromotor deficits or additional complications, was discharged after the family was provided with information about pin-bottom dressing every other day. The sutures were removed in the 2nd post-operative week, the cast was terminated in the 4th week, and gentle ROM exercises for the elbow and wrist were initiated. In the 6th week (Fig. 6), due to the maintenance of the reduction and the presence of union in the osteotomy line, the K-wires were removed in the outpatient clinic with a sterile drape. The patient was referred to physical therapy and rehabilitation for stretching and strengthening exercises. At the 3-month follow-up (Fig. 7), painless full ROM was achieved without any restriction in pronation and supination of the elbow and forearm.

At the 1-year follow-up examination, there was a 3 cm incision scar in the posterior elbow, and the ROM of the elbow joint was fully (Fig. 8). The Grace and Eversmann criteria were used to evaluate union, pronation, and supination. The Mayo Elbow Performance Score (MEPS) was used to assess overall elbow function and limitations. There were excellent results according to the Grace and Eversmann criteria and the MEPS.

Due to the absence of significant deformity and pain after simple falls in the pediatric age group and the patient being too young to express herself, families may not present to the hospital, thinking there is no need to go to the doctor. In our case, it was found that a serious injury (Monteggia fracture-dislocation) had been neglected in our patient, who presented due to swelling and a click noise in the elbow.

“Ulnar bow sign” was defined radiographically in true lateral radiographs [1]. It has been reported that the line extending along the posterior border of the ulna on the lateral radiograph should be straight, and any deviation in this line should lead to suspicion of ulnar bowing and concomitant radial head subluxation or dislocation [1]. Plastic ulnar bowing is usually due to a longitudinal compression force applied to the naturally curved bone rather than direct trauma [13]. A neglected type I Monteggia injury involving plastic ulnar bowing was detected in our patient at the time of diagnosis.

In planning the patient’s treatment, we felt that the radiocapitellar joint was easily closed and reduced, so we chose to follow the patient conservatively during the following 8 months. This treatment process failed after 1 week of conservative follow-up. According to the literature, a definite time interval has not been determined for how long the time should be from the first injury to treatment related to a conservative closed reduction attempt. This shows that even if radiocapitellar reduction is achieved, the reduction will eventually fail in cases, where the ulnar length cannot be achieved. Most authors describe a 4-week delay in treatment as a chronic Monteggia lesion that is no longer amenable to closed reduction [3, 6-8]. In parallel with our opinion, it has been reported that ulnar osteotomy is required to achieve complete reduction of some radial head dislocations, despite adequate debridement of the capsuloligamentous tissue, in the treatment of missed Monteggia lesions [6]. Kalamchi was the first author to recommend ulnar osteotomy as the primary aim of achieving radial head reduction [9]. He reported that residual ulnar deformity disrupts the reduction of the radial head through the interosseous membrane and that the radial head may be reduced after correction of the ulnar deformity.

Numerous case series related to the ulnar osteotomy method have been reported in the treatment of missed and neglected Monteggia lesions, while surgical techniques have shown various changes in almost every case series [4, 6, 9, 14]. However, the most commonly used methods for radiocapitellar joint reduction have been repairing or reconstructing the annular ligament with an ulnar osteotomy [6-8]. Some authors have claimed that open reduction of the radial head is unnecessary [10-14]. Leaderman et al. reported that closed reduction of the radiocapitellar joint could be achieved by lengthening the ulna and correcting the angular deformity with an ulnar osteotomy in six patients [10]. Bor et al. [12] described a closed reduction of the radiocapitellar joint using the Ilizarov technique to gradually lengthen and correct the angular deformity of the ulna from the ulnar osteotomy site through callotasis. Koslowsky et al. [11] used a percutaneous osteotomy of the ulna, fixed the ulna with a unilateral fixator, and reduced the radial head as closed. As far as we could review the literature, the youngest neglected Monteggia injury detected outside of our case was a 14-month-old patient with a history of birth trauma [14]. The radial head could be reduced by providing over correction with an ulnar osteotomy with a unilateral external fixator. These studies reported short and long-term results in ROM, with nearly complete forearm pronation (mean 85°, range 70–90°) and supination (10° loss) obtained [10-14]. In our case, we preferred to apply only an osteotomy to the ulna to ensure the maintenance of this reduction, since radiocapitellar joint reduction could be achieved closed. According to the MEPS and Grace and Eversmann criteria, we achieved an excellent result by providing full ROM in this case.

Since no fixation method was used for fixation after ulnar osteotomy, various methods, including elastic nail, K-wire, plate, and more recently external fixation, have been used [6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14]. It has been suggested that the ulna will naturally remodel over time due to the lack of a fixation method in the osteotomy line [9]. Apart from this, we reported the advantages and disadvantages of other ulnar fixation materials used in pediatric cases in our previous study [15]. As we suggest in acute unstable ulnar fracture patterns, intramedullary fixation methods should be chosen first after osteotomy. In this case, in addition to the intramedullary K wire, we also increased the fixation with two oblique K-wires to provide rotational stability. The patient’s existing K-wires were removed under outpatient conditions. Due to the fact that the external fixator is large for the age of the patient, it restricts the comfort of both the mother and child and also brings additional costs. Considering the child’s very young age and bone development for plate applications, it would be challenging to find the appropriate plate-screw configuration at such a young age, which would bring additional costs. In addition, after methods such as plate and fixator, implant removal must be performed in the operating room [6, 11, 12, 14].

The most frequently stated criteria for surgical intervention are dislocation of the radial head for less than 3 years and being under the age of 12 [6]. In addition, it has been reported that the radial head can be successfully reduced if treated within 1 year after the first injury, regardless of age [6]. Therefore, it can be suggested that these numbers provide information to be used as a guide for surgeons instead of strict criteria, and that each case should be evaluated individually.

This case report is noteworthy in showing that because of the patient’s young age, delayed diagnosis, and ulnar bowing, conservative treatment with closed reduction without ulnar osteotomy cannot ensure maintenance of the reduction. If closed radiocapitellar reduction can be achieved in the treatment of neglected Monteggia injuries, ulnar length should be achieved with minimally invasive fixation methods.

Even if closed radiocapitellar reduction is achieved in the treatment of neglected Monteggia injuries, in cases, where the ulnar length cannot be achieved, the reduction will ultimately fail. Therefore, ulnar osteotomy should be applied in treatment. For the fixation of the osteotomy, intramedullary fixation should especially be at the forefront, and we recommend using K-wires as the fixation materials that should be chosen first.

References

- 1.1. Lincoln TL, Mubarak SJ. “Isolated” traumatic radial-head dislocation. J Pediatr Orthop 1994;14:454-7. [Google Scholar]

- 2.2. Singh V, Dey S, Parikh SN. Missed diagnosis and acute management of radial head dislocation with plastic deformation of ulna in children. J Pediatr Orthop 2020;40:e293-9. [Google Scholar]

- 3.3. Delpont M, Louahem D, Cottalorda J. Monteggia injuries. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res 2018;104:S113-20. [Google Scholar]

- 4.4. Fowles JV, Sliman N, Kassab MT. The monteggia lesion in children. Fracture of the ulna and dislocation of the radial head. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1983;65:1276-82. [Google Scholar]

- 5.5. Ring D, Waters PM. Operative fixation of monteggia fractures in children. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1996;78:734-9. [Google Scholar]

- 6.6. Hubbard J, Chauhan A, Fitzgerald R, Abrams R, Mubarak S, Sangimino M. Missed pediatric monteggia fractures. JBJS Rev 2018;6:e2. [Google Scholar]

- 7.7. Stoll TM, Willis RB, Paterson D. Treatment of the missed monteggia fracture in the child. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1992;74:436-40. [Google Scholar]

- 8.8. Nakamura K, Hirachi K, Uchiyama S, Takahara M, Minami A, Imaeda T, et al. Long-term clinical and radiographic outcomes after open reduction for missed monteggia fracture-dislocations in children. J Bone Joint Surg 2009;91:1394-404. [Google Scholar]

- 9.9. Kalamchi A. Monteggia fracture-dislocation in children. Late treatment in two cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1986;68:615-9. [Google Scholar]

- 10.10. Lädermann A, Ceroni D, Lefevre Y, De Rosa V, De Coulon G, Kaelin A. Surgical treatment of missed monteggia lesions in children. J Chil Orthop 2007;1:237-42. [Google Scholar]

- 11.11. Koslowsky TC, Mader K, Wulke AP, Gausepohl T, Pennig D. Operative treatment of chronic monteggia lesion in younger children: A report of three cases. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2006;15:119-21. [Google Scholar]

- 12.12. Bor N, Rubin G, Rozen N, Herzenberg JE. Chronic anterior monteggia lesions in children: Report of 4 cases treated with closed reduction by ulnar osteotomy and external fixation. J Pediatr Orthop 2015;35:7-10. [Google Scholar]

- 13.13. Malik M, Demos TC, Lomasney LM, Stirling JM. Bowing fracture with literature review. Orthopedics 2016;39:e204-8. [Google Scholar]

- 14.14. Smith WR, Kozin SH, Zlotolow DA. Delayed treatment of a neonatal Type-I monteggia fracture-dislocation: A case report. J Pediatr Orthop B 2018;27:142-6. [Google Scholar]

- 15.15. Ozturk T, Erpala F, Zengin EC, Gedikbas M, Eren MB. Surgical treatment with titanium elastic nail (TEN) for failed conservative treatment of acute monteggia lesions in children. J Pediatr Orthop 2021;41:597-603. [Google Scholar]