In patients with end stage osteoarthritis of the hip secondary to Klippel-Trenaunay Syndrome a pre-operative MRI can potentially reveal a relatively safe access to the hip joint which allows these high risk patients to undergo successful joint replacement.

Dr. Georges Frederic Vles, Department of Orthopaedics, University Hospitals Leuven - Gasthuisberg, Herestraat 49, 3000 Leuven, Belgium. E-mail: georges.vles@uzleuven.be

Introduction:Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome (KTS) affects the development of blood vessels, soft tissues (such as skin and muscles), and bone. It is a rare cause of severe degenerative joint disease at an early age. Orthopedic interventions in these patients bring numerous difficulties for various reasons. Up to this point, only six cases of attempted total hip arthroplasty (THA) in patients with KTS have been reported in the literature. The two most recent cases were prematurely aborted due to excessive bleeding and imminent risk of exsanguination. One of the most recent published case reports suggested that hip joint replacement should be avoided in this patient population.

Case Report:A middle-aged female presented with end stage coxarthrosis secondary to KTS. A thorough workup was performed and magnetic resonance imaging revealed that the direct anterior interval was relatively free of vascular malformations. After intensive work-up, uneventful THA was performed, resulting in dramatic improvement of quality of life.

Conclusion:Effort should be put into identifying those patients with a relatively easy accessible joint so they are not unnecessarily being denied successful joint replacement.

Keywords:Klippel-Trenaunay Syndrome, THA, Total hip arthroplasty, Vascular malformations, Surgical approach.

Klippel-Trenaunay Syndrome (KTS) or Capillary, Lymphatic, and Venous Malformation Syndrome is a low-flow vascular syndrome due to somatic mutations in the PIK3CA gene [1]. It is characterized by a segment anomaly with a clinically triad of an extensive port-wine stain, underlying venous and lymphatic malformations, and hypertrophy of bone and soft tissues. The lower limb is most often affected and patients can suffer from venous engorgement, painful thrombophlebitis, eczema, lipodermatitis, and can be at high risk for thrombovenous events, especially in the presence of persistent embryonic (lateral margin or sciatic) veins [2]. Patients are furthermore prone to intravascular coagulopathies with risk of both bleeding and clotting [3]. From an orthopedic point of view, the vascular malformations can give way to a multitude of musculoskeletal problems leading to pain, deformity, and loss of function [4]. Intra-articular lesions can cause abnormal bony architecture [5], but can also induce synovial inflammation and hemarthrosis triggering a complex enzymatic cascade of cartilage disintegration [6]. Leg length discrepancy can worsen abnormal biomechanics and may cause joint overload. Therefore, patients may present themselves with end stage secondary osteoarthritis of the hip and as such have an indication for joint replacement. However, the old adage goes that treatment of orthopedic disorders in patients with KTS should be as conservative as possible [7, 8]. Up to this point, only six cases of attempted total hip arthroplasty (THA) in this group of patients have been reported in the literature with the two most recent cases prematurely aborted due to excessive bleeding and imminent risk of exsanguination (Table 1). Hence, these substantial dangers might make the patient and medical team decide to accept living with end stage osteoarthritis, even when conservative treatment modalities have been exhausted. Although this might be perceived as the easy way out from a surgeon’s point of view, life should always go before limb and nobody benefits from unsuccessful attempts at joint replacement.

However, no patient with KTS is the same, and a thorough work-up just might reveal options for joint replacement in a relatively safe manner. We report such a case of uneventful THA in a patient with severely debilitating osteoarthritis of the hip secondary to KTS. Perioperative considerations and the available literature are discussed.

A 53-year-old female with KTS (height: 165 cm and body weight: 78 kg) presented to our hip clinic because of incremental right-sided hip pain. She underwent a resection of a persistent lateral marginal vein (of Servelle) 30 years earlier. Physical examination revealed overgrowth of her right leg and port-wine stains on the lateral and anterolateral aspect of her right thigh (Fig. 1). Radiographs revealed a dysplastic right hip with joint space narrowing, subchondral sclerosis, and acetabular cyst formation, but without osteophytes (Fig. 2a).

Conservative treatment was initiated including regular use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, physiotherapy, and an intra-articular injection with corticosteroids. Unfortunately, her symptoms worsened and follow-up radiographs showed rapid deterioration of the hip joint (Fig. 2b, c). A magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was performed to investigate the extent of the vascular malformations surrounding the hip. Widespread networks of varicose veins were seen on the lateral and posterior aspects of the hip, impeding the use of a posterolateral or direct lateral approach for THA. However, the anterior soft tissues, but also the proximal femur and the acetabulum, appeared relatively free of vascular deformities (Fig. 3).

After multi-disciplinary consultation, she was offered a THA through a direct anterior approach. Blood works revealed completely normal coagulation tests, that is, PT (sec) 12.5, PT (%) 83.0, International normalized ratio (prothrombin time) 1.1, and Activated partial thromboplastin time (sec) 30.7. On the day of surgery, a vascular surgeon was standby in case of uncontrollable bleeding and four cross-matched packed cells were available. A cell-saver was installed to collect blood for auto-transfusion. Following general anesthesia, a urinary catheter, two large bore peripheral venous catheters, and an arterial line were inserted. Standard prophylactic antibiotics (Cefazolin) and tranexamic acid were given. A slightly larger than normal incision was used (Fig. 4).

Several large veins were encountered overlying the Tensor fascia latae and underneath the innominate fascia. Care was taken to place all retractors under direct vision. Massive hydrops was met when opening the joint capsule. After osteotomy of the femoral neck, limited releases of the superior and inferior capsule were performed. The acetabulum was reamed and a hemispherical cup with a highly cross-linked polyethylene liner (Pinnacle cup, DePuy Synthes, Warsaw, Indiana) was impacted. The femoral canal was broached sequentially and no major intraosseous bleeding was encountered. A fully coated and collared uncemented stem was impacted (Corail Stem, DePuy Synthes, Warsaw, Indiana) and a ceramic head was seated onto its taper. Meticulous hemostasis was followed by a layered closure. Estimated blood loss totaled 600 ml. The cell saver had collected 300 ml and this was considered not enough for auto-transfusion. Hemoglobin levels dropped from 14.1 g/dL preoperatively to 10.1 g/dL on day 1 and 9.4 g/dL on day 3. The patient was mobilizing on the day of surgery. VTE prophylaxis consisted of Enoxaparine 40 mg subcutaneous injections once daily continued for 6 weeks and the patient’s own graded compression garment. The post-operative course remained uneventful and she could be discharged home on the 3rd post-operative day. At outpatient follow-up 6 weeks (Fig. 5) later, PROMs had improved from Hip disability and osteoarthritis outcome score (HOOS) 19, Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC) 26, HSS 43, European Quality of Life Five Dimension (EQ-5D) 42431, Visual analog scale (VAS) 40 preoperatively to HOOS 89, WOMAC 91, Harris Hip Score 84, EQ-5D 11111, and VAS 75 postoperatively, respectively. At 8 weeks after, the patient was admitted to the emergency department with pain around the right hip. A superficial thrombophlebitis of the malformations was diagnosed with ultrasound investigation and low molecular weight heparin was prescribed as treatment.

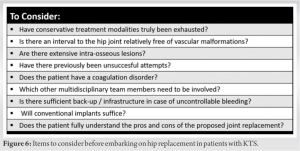

This study describes a relatively straight-forward THA in a patient with KTS resulting in drastic improvements in pain, function, and quality of life. No complications occurred in the perioperative period but a superficial thrombophlebitis of one of the vascular malformations was diagnosed 8 weeks after surgery. This report follows two recent reports where attempts for THA had to be aborted prematurely due to risk of exsanguination [7, 8]. A comprehensive workup is of vital importance before deciding on joint replacement in patients with KTS. Advanced imaging needs to be performed and when studying the images attentively, most problems associated with the surgical approach can be anticipated. MRI seems to be modality of choice [9, 10]. It has been found accurate in assessing the extent of venous malformations. Conventional angiography alone may not reveal the true extent of vascular malformations [11]. The multisystem organization may prevent collapsed veins to fill with contrast. Even with MRI, one must realize that filling and cross-sectional areas of veins are affected by position and even hydration status [12]. When contemplating a direct anterior approach to the hip joint, an MRI in prone position might be indicated. Patients should be checked for consumptive coagulopathy and severe hypofibrinogenemia can be corrected before surgery [13]. In contrast to persistent embryonic veins, the complex and extensive networks of varicose veins are often not suited for pre-emptive embolization. Nevertheless, it is advised to discuss options with the interventional radiologist. Patients should be discussed in a multidisciplinary team meeting, including delegates from orthopedics, hematology, anesthesiology, vascular surgery, and interventional radiology. Important risk factors for unsuccessful joint replacement appear to be previous failed attempts, the absence of an interval free of vascular malformations, and extensive intraosseous lesions. When it is decided to go ahead with joint replacement, one should hope for the best, but prepare for the worst [Fig. 6]. This includes gathering an experienced surgical team, ordering sufficient blood transfusion products, and most of all, having back-up ready in case of massive blood loss. The latter includes intraoperative support by a vascular surgeon and anesthesiologist, but also post-operative support from an Intensive Care Unit. Achieving equal leg length might be challenging as the involved leg typically is already longer. After successful joint replacement, outcomes are likely to be excellent. Although there of course are no extensive long-term data on hip replacements in patients with KTS, results obtained in other groups with arthropathy due to recurrent intra-articular bleeds (e.g. haemophilia) show that implant survival is high and complications are relatively rare at mid-term to long-term follow-up [14]. Despite theoretical concerns about bone quality in patients with KTS, most groups report bone of adequate composition and the use of uncemented primary implants. Even though it has been suggested to use cemented stems in cases with extensive intramedullary vascular malformations to control potential bleeding [15], we would be concerned about massive cement emboli and, therefore, prefer uncemented stems if femoral morphology allows. The literature indicates that patients with KTS have higher rates of pulmonary embolisms and deep vein thrombosis after surgery [5] and adequate prophylactic anticoagulation must be given.

We presented a case of a middle-aged female suffering from end stage coxarthrosis secondary to KTS. An MRI scan was performed in the work up and it revealed that the direct anterior interval was relatively free of vascular malformations. A successful THA operation was performed, resulting in dramatic improvement of quality of life. A solid work up is vital in these cases and decision making should be done multidisciplinary. Effort should be put into identifying those patients with a relatively easy accessible joint so they are not unnecessarily being denied successful joint replacement. When surgery is chosen, preparations must be made to put together an experienced surgical team, order sufficient blood transfusion products, and arranging back-up expertise in case of massive blood loss. After surgery adequate prophylactic anticoagulation must be provided as the risks of deep vein thrombosis is increased in these patients.

Both the risks and rewards of THA in patients with KTS can be high. The decision to operate should not be taken lightly and there are many factors to consider. There is no shame in taking the easy way out in patients at high risk for unsuccessful joint replacement. On the other hand, effort should be put into identifying those patients with an easy way in so they are not unnecessarily being denied what could be a very successful joint replacement.

References

- 1.Alomari AI. Klippel-trenaunay syndrome: The quest for the proper diagnosis. Ann Vasc Surg 2012;26:443-4. [Google Scholar]

- 2.John PR. Klippel-trenaunay syndrome. Tech Vasc Interv Radiol 2019;22:100634. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gianlupi A, Harper RW, Dwyre DM, Marelich GP. Recurrent pulmonary embolism associated with klippel-trenaunay-weber syndrome. Chest 1999;115:1199-201. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Spencer SA, Sorger J. Orthopedic issues in vascular anomalies. Semin Pediatr Surg 2014;23:227-32. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee A, Driscoll D, Gloviczki P, Clay R, Shaughnessy W, Stans A. Evaluation and management of pain in patients with klippel-trenaunay syndrome: A review. Pediatrics 2005;115:744-9. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hooiveld M, Roosendaal G, Vianen M, Van den Berg M, Bijlsma J, Lafeber F. Blood-induced joint-damage: Longterm effects in vitro and in vivo. J Rheumatol 2003;30:339-44. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cirstoiu C, Cretu B, Sandu C, Dorobat B, Neagu A, Serban B. Failed attempt of total hip arthroplasty in a patient with klippel-trenaunay syndrome: A case report. JBJS Case Connect 2019;9:e0103. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lopreite FA, Rodríguez J, Tillet F, Gaggiotti S, Cullari LM, Sel HD. Paciente con síndrome de klippel-trenaunay. Reporte de un caso de reemplazo articular de cadera suspendido durante la cirugía. Rev Asoc Argent Orthop Traumatol 2021;86:240-5. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Elsayes KM, Menias CO, Dillman JR, Platt JF, Willatt JM, Heiken JP. Vascular malformation and hemangiomatosis syndromes: Spectrum of imaging manifestations. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2008;190:1291-9. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Das R, Kumar I, Verma A, Shukla RC. Spectrum of imaging findings in klippel-trenaunay syndrome affecting lower limbs: A report of three cases. Egypt J Radiol Nucl Med 2019;50:104. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mavili E, Ozturk M, Akcali Y, Donmez H, Yikilmaz A, Tokmak TT, et al. Direct CT venography for evaluation of the lower extremity venous anomalies of klippel-trénaunay syndrome. Am J Roentgenol 2009;192:w311-6. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Behzadi AH, Khilnani NM, Zhang W, Bares AJ, Boddu SR, Min RJ, et al. Pelvic cardiovascular magnetic resonance venography: Venous changes with patient position and hydration status. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson 2019;21:3. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Coloma-Pérez M, Hernández-Palazón J, Fuentes-García D, Falcón-Araña L. Preoperative replacement therapy with fibrinogen concentrate in a patient with klippel-trenaunay syndrome and severe hypofibrinogenaemia. Br J Anaesth 2013;110:855-6. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carulli C, Felici I, Martini C, Civinini R, Linari S, Castaman G, et al. Total hip arthroplasty in haemophilic patients with modern cementless implants. J Arthroplasty 2015;30:1757-60. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mallick A, Weeber AC. An experience of arthroplasty in klippel-trenaunay syndrome. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol 2007;17:97-9. [Google Scholar]