The clinician should always have a high index of suspicion not to miss isolated cerebral fat embolism while managing polytrauma patients, even when the classical signs of fat embolism are not evident.

Dr. Thankappan Ajayakumar, Department of Orthopaedics, Apollo Adlux Hospital, Kerala - 683 576, India. E-mail: drtajay@gmail.com

IntroductionIsolated cerebral fat embolism syndrome (FES) is a rare complication that occurs within the first 3 days of the initial insult. We report a case of multiple long bone fractures with isolated cerebral FES, despite undergoing early total care with definitive fixation.

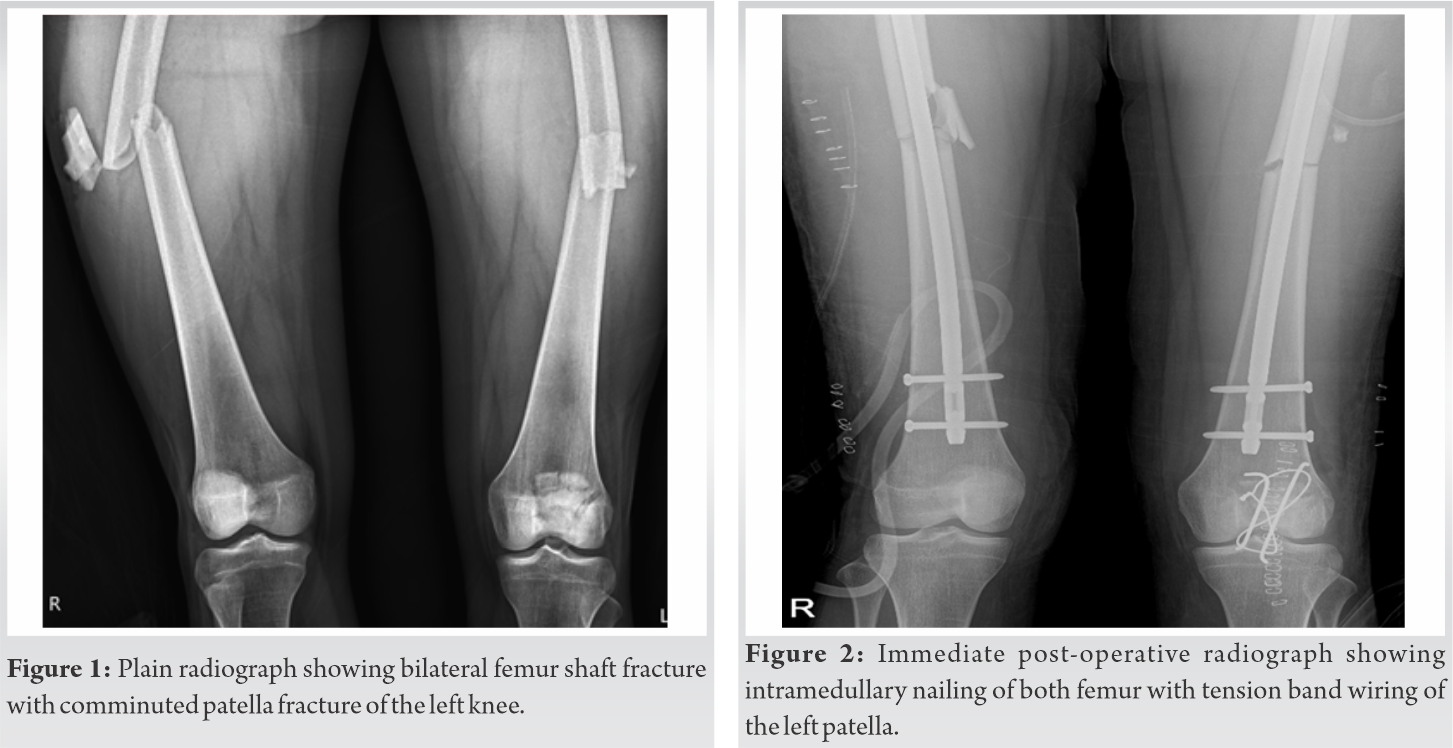

Case PresentationA 22-year-old female presented with type IIIA open femur shaft fracture on the right side (AO 32B2), closed femur shaft fracture (AO 32B2), comminuted patella fracture on the left side (AO 34C3), and undisplaced mandible fracture. She had a normal sensorium with a Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) of E4V5M6. A whole body computed tomography (CT) scan was done to rule out other injuries. All initial scans were normal. After about 6 h in the ICU, she was noticed to have disconjugate gaze and was answering in monosyllables. A repeat CT scan of the brain was normal. The early total care and definitive fixation with titanium intramedullary nails for femur fractures and tension band wiring for patella was done under general anesthesia. On 1st post-operative day (POD), her GCS dropped to E1VTM1. On the 3rd POD, she developed decerebrate rigidity and generalized tonic clonic seizures. Fundoscopic examination showed multiple fat globules along the vessel in the entire field of both eyes. Since there were no other signs of FES in the lungs or on the skin, an MRI brain was done which revealed a hyperintensive starfield pattern on diffusion-weighted images, suggestive of cerebral fat embolism (CFE). At 4 weeks, her upper limb and lower limb muscle power improved. By 2 months, she was mobilized with support. Her Mini-Mental State Examination showed no cognitive impairment. At the latest follow-up at 1 year, her fractures are completely healed and she has no neurological or functional impairment.

ConclusionWe must always suspect isolated cerebral FES as a diagnosis in polytrauma patients even when the classical findings are not present. MRI compatible implants have to be used as far as possible as MRI may be required to confirm the diagnosis of CFE. The early total care with definitive fixation and supportive treatment helped us in this patient’s complete recovery without cognitive impairment.

KeywordsCerebral fat embolism, bilateral femur fracture, polytrauma, fat embolism syndrome.

Fat embolism syndrome (FES) is a potentially rare complication of long bone fractures. The incidence of FES in long bone fractures is 0.9–2.2% [1], commonly seen in long bone fractures. The lipid droplets from ruptured marrow fat cells enter the blood stream through the broken small vein and block the small vessels causing FES [2]. According to Gurd and Wilson, the diagnosis of FES could be made if one major feature, four minor features, and fat macroglobulinemia were present [3]. Major criteria are petechial rash, respiratory symptoms plus bilateral lung signs with positive radiographic changes, and cerebral signs unrelated to head injury. Minor criteria are tachycardia, pyrexia, retinal fat or petechiae, urinary fat globules, sudden drop in hemoglobin, and sudden thrombocytopenia. About 75% of FES have respiratory symptoms and 86% had cerebral changes [4]. However, isolated cerebral fat embolism (CFE) without pulmonary involvement is rare. CFE is even more difficult to diagnose. Patients with CFE typically present with a wide range of post-operative neurologic dysfunctions, commonly in the 24–72 h. The early diagnosis and treatment of CFE requires a high index of suspicion and knowledge of the diagnostic work-up. In this article, we report a case of a 22-year-old female who developed CFE without any respiratory signs after multiple long bones fractures, despite undergoing early total care with intramedullary nailing. Cerebral involvement in the absence of pulmonary or dermatological manifestation on initial presentation may delay the diagnosis of CFE. The early MRI brain (diffusion-weighted images and T2-weighted sequences) to be considered in polytrauma patients having neurological symptoms with a normal CT scan, even in the absence of pulmonary and dermatological findings.

A 22-year-old previously healthy female came to hospital emergency room with multiple fractures following fall from height. She had closed femur shaft fracture (AO 32B2) and comminuted patella fracture on the left side (AO 34C3), type IIIA open femur shaft fracture on the right side (AO 32B2), and undisplaced mandible fracture (Fig. 1). A whole body computed tomography (CT) scan revealed no other injuries. She was planned for the early total care with definitive fixation since she was a borderline patient (ISS score 17). Before taking up for fixation, a repeat CT scan of brain was done at 8 h post-injury as she was noticed to have disconjugate eye movements and monosyllable speech. The repeat CT also showed no cerebral bleed. About 10 h post injury, she was taken to the operating room. She underwent debridement of the right thigh wound, bilateral femur antegrade nailing with minimal reaming and tension band wiring of the left patella fracture (Fig. 2). Surgery lasted for 5 h with no hypotension or hypoxia intraoperatively. She was ventilated overnight and on reassessing her on 1st post-operative day (POD), she was not responding to commands and not moving her limbs. Her Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) was E1VTM1 and remained until POD5. Her chest X-ray and CT brain were normal. On POD 1, she had pyrexia, tachycardia, anemia, and thrombocytopenia. On POD 3, she developed features of decerebrate rigidity and later generalized tonic clonic seizures. Fundoscopic examination showed multiple fat globules along the vessel in the entire field of both eyes. Since there were no pulmonary or dermatological signs of FES, an MRI of brain was done which revealed hyper intensive starfield pattern on diffusion-weighted image, suggestive of FES (Fig. 3). Supportive treatment with antiepileptics, antibiotics, and anticoagulants was given.

After 2 weeks, her sensorium improved and gaze became normal with grade 3 power of upper and lower limb muscles and was subsequently extubated. And by 4 weeks, she was able to sit with support and was able to swallow. By 2 months, she was mobilized with support. Her Mini-Mental State Examination showed no cognitive impairment. By 6 months, she had complete recovery and started attending classes for her higher education. At the latest follow-up at 1 year, her fractures healed completely and she was able to perform all her daily life activities independently and has no neurological deficit (Fig. 4, 5).

FES is usually seen in the second and third decades of life and within 12–72 h post-trauma [5]. The early stabilization can decrease the incidence of fat embolism. In our case, the patient underwent early total care within 10 h of injury but developed fat embolism. Hence, the early surgery might decrease the risk but not eliminate fat embolism. The fat emboli passes to the lungs through blood circulation and mechanical occlude the capillaries and leads to pulmonary dysfunction which further develops to acute respiratory distress syndrome and may even cause death. CFE without pulmonary complications can be due to small diameter fat droplets (<7–20 um), which can pass through the pulmonary capillaries or foramen ovale into the systemic circulation, but get lodge in cerebral vessels [6]. When the excitatory neurotransmitter depletes, patients become drowsy and unconscious [2]. This explains why our case with CFE became unconscious 24 h after injury.

CFE lesions found to be higher in the basal ganglia, followed by the juxtacortical regions of the frontal, parietal, and temporal lobes. In particular, there is a clear involvement of the anterior circulation of brain than posterior circulation. The involvement of the posterior fossa structures is rare [7]. Our case also had only motor function disturbance and decerebrate rigidity. FES diagnosis is based on Gurd and Wilson’s criteria [3]. Our patient had one major criterion (altered sensorium) and four minor criteria (pyrexia, anemia, thrombocytopenia, and tachycardia) which do fulfill the diagnostic criteria for FES. However, radiological evaluation of brain with MRI is very important in confirming the diagnosis when the classical signs are absent. CT scan of the brain does not help in the diagnosis of FES and may be found normal. However, it can be used to rule out the intracranial bleed which can impair consciousness. MRIs have a huge role in diagnosing CFE. Multiple hyperintense punctate lesions on the diffusion-weighted MRI (DW MRI) appear as starfield pattern of scattered bright spots on a dark background, which is a classical finding for cerebral FES [8]. Another differential diagnosis with starfield pattern in DW MRI is diffuse axonal injury (DAI). However, DAI usually presents with immediate impairment of consciousness after trauma [9]. Our case has typical MRI findings with gradual loss of consciousness, which helped to confirm the diagnosis of cerebral FES after ruling out other intracranial lesions.

FES in patients with bilateral femur fractures was found to have higher death rates (5–15%) compared to unilateral femur fractures [10]. CFE is usually self-limiting with a good prognosis characterized by complete recovery within a few months or years. Neurological symptoms of FES can be transient and highly varied from diffuse encephalopathy to focal deficits ranging from mild personality changes, amnesia, or cognitive dysfunction [11]. Pinney et al. reported that early intramedullary nailing of femur fractures decreases the incidence of FES especially in patients below 35 years. They conclude that patients with isolated femoral fractures should undergo nailing performed as early as possible after injury to minimize FES [12]. The intramedullary pressure and the incidence of fat embolism were significantly less with reamed nailing when compared to unreamed nailing. The reamers with smaller shaft diameter and increased reamer flutes produces less pressure compared to standard reamers [13]. We used flexible intramedullary reamers (SYNTHES) which are deeply fluted and have a thin flexible shaft, which are designed to reduce intramedullary pressure and to allow flow of bone chips and marrow contents [14]. The early immobilization and stabilization, with external or internal fixation in long-bone fractures, can prevent CFE/FES. In established CFE, the treatment is mainly supportive with adequate oxygenation, antiepileptic drugs, and anticoagulants for stroke prophylaxis [4]. We strongly believe that the complete recovery of our patient is due to the prompt diagnosis of CFE and more importantly due to the early immobilization of the fractures, which were the precipitants of this pathology. A high index of suspicion of CFE should be there in polytrauma when the patient has gradually deteriorating sensorium with no intracranial bleed.

We must always suspect isolated cerebral FES in polytrauma patients even when the classical findings are not present. MRI compatible implants have to be used as far as possible as MRI may be required to confirm the diagnosis of CFE. The early total care with definitive fixation and supportive treatment helped us in this patient’s complete recovery without cognitive impairment.

There are only few published reports on isolated CFE. A high index of clinical suspicion of CFE should be there in polytrauma when the patient has gradually deteriorating sensorium with no intracranial bleed. The early total care with definitive fixation may improve the outcome. MRI compatible implants have to be used as far as possible as MRI may be required to confirm the diagnosis of CFE.

References

- 1.1. Tsai IT, Hsu CJ, Chen YH, Fong YC, Hsu HC, Tsai CH. Fat embolism syndrome in long bone fracture: Clinical experience in a tertiary referral center in Taiwan. J Chin Med Assoc 2010;73:407-10. [Google Scholar]

- 2.2. Zhou Y, Yuan Y, Huang C, Hu L, Cheng X. Pathogenesis, diagnosis and treatment of cerebral fat embolism. Chin J Traumatol 2015;18:120-3. [Google Scholar]

- 3.3. Gurd AR, Wilson RI. Fat embolism: An aid to diagnosis. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1970;56:732-7. [Google Scholar]

- 4.4. Shaikh N. Emergency management of fat embolism syndrome. J Emerg Trauma Shock 2009;2:29-33. [Google Scholar]

- 5.5. Huang CK, Huang CY, Li CL, Yang JM, Wu CH, Chen CH, et al. Isolated and early-onset cerebral fat embolism syndrome in a multiply injured patient: A rare case. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2019;20:377. [Google Scholar]

- 6.6. James PB. Hyperbaric oxygenation in fluid microembolism. Neurol Res 2007;29:156-61. [Google Scholar]

- 7.7. Vetrugno L, Bignami E, Deana C, Bassi F, Vargas M, Orsaria M, et al. Cerebral fat embolism after traumatic bone fractures: A structured literature review and analysis of published case reports. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med 2021;29:47. [Google Scholar]

- 8.8. Parizel PM, Demey HE, Veeckmans G, Verstreken F, Cras P, Jorens PG, et al. Early diagnosis of cerebral fat embolism syndrome by diffusion-weighted MRI (starfield pattern). Stroke 2001;32:2942-4. [Google Scholar]

- 9.9. Eguia P, Medina A, Garcia-Monco JC, Martin V, Monton FI. The value of diffusion-weighted MRI in the diagnosis of cerebral fat embolism. J Neuroimag 2007;17:78-80. [Google Scholar]

- 10.10. Nork SE, Agel J, Russell GV, Mills WJ, Holt S, Routt ML Jr. Mortality after reamed intramedullary nailing of bilateral femur fractures. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2003;415:272-8. [Google Scholar]

- 11.11. Al-Shaer DS, Ayoub O, Ahamed NA, Al-Hibshi AM, Baeesa SS. Cerebral fat embolism syndrome following total knee replacement causing a devastating neurocognitive sequelae. Neurosciences 2016;21:271-4. [Google Scholar]

- 12.12. Pinney SJ, Keating JF, Meek RN. Fat embolism syndrome in isolated femoral fractures: Does timing of nailing influence incidence? Injury 1998;29:131-3. [Google Scholar]

- 13.13. Högel F, Gerlach UV, Südkamp NP, Müller CA. Pulmonary fat embolism after reamed and unreamed nailing of femoral fractures. Injury 2010;41:1317-22. [Google Scholar]

- 14.14. Available from: http://synthes.vo.llnwd.net/o16/LLNWMB8/S%20Mobile/Synthes%20North%20America/Product%20Support%20Materials/Technique%20Guides/Final%20Approved%20Technique%20guide%20Clean%20Copy%20%2011-14-17.pdf [Google Scholar]