Localized Pigmented Villonodular Synovitis (LPVNS) is a very rare disease and it is silent and insidious, symptoms are non-specific, nevertheless, orthopedic surgeons should keep this entity in mind.

Dr. Mehmet Sukru Sahin, Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Baskent University Alanya Research and Practice Center, Alanya, Turkey. E-mail: mhmskrsahin@yahoo.com

BackgroundThe localized form is characterized by local participation of the synovium as a nodule or pedunculated mass. The incidence rate of PVNS is estimated to be 1.8 per million people – the localized type is just one-quarter of that. The aim of this study is to remind orthopedic surgeons about the unusual properties of LPVNS located in the knee.

Case ReportA 39-year-old man presented to our clinic with pain and discomfort in his right knee. Magnetic resonance imaging showed an intra-articular mass in the infrapatellar region of the knee adjacent to the Hoffa fat pad. The mass was hypointense in the T1 sequence and heterogeneously hyperintense in the T2 sequence, which may be considered a local type of tenosynovial giant cell tumor (LPVNS). Excision was carefully performed without penetrating the tumor. The macroscopic appearance of the tumor was yellow-reddish and brown in color. Histopathologic examination revealed pigmented villonodular synovitis of the local type.

ConclusionEven though the LPVNS of the knee is an uncommon intra-articular phenomenon, orthopedic surgeons should not overlook this lesion based on imaging findings, and open excision should be regarded as a reliable treatment option.

Keywords Pigmented Villonodular Synovitis, Synovial Tumor Like Lesions, Knee pain, Intraarticular Mass.

Jaffe et al. coined the term “PVNS” for the first time in 1941 [1]. Pigmented villonodular synovitis (PVNS) most frequently occurs in the knee as a proliferative phenomenon that involves the synovial membrane [2, 3]. It is considered a benign lesion of unknown etiology. Some authors postulate that it is probably caused by inflammation, trauma, toxins, allergies, clonal chromosomal abnormalities, or aneuploidy [4, 5]. The disease can be classified into two types: diffuse and localized. The diffuse form (DPVNS), as the name indicates, attacks practically the entire synovial cellular membrane of the affected joint. The localized form (LPVNS) is characterized by local participation of the synovium as a nodule or pedunculated mass. This type is generally a solitary mass of pedunculated or, much less frequently, 2–3 nodules yellowish-brown in color [6, 7, 8, 9, 10]. When LPVNS affects the knee, it is generally located in the anterior compartment [6, 7]. The incidence rate of PVNS is estimated to be 1.8 per million people—the localized type is just one-quarter of that [11]. Approximately 85% of PVNS occurs in the fingers, whereas 12% of the tumors are located in the knee, elbow, hip, and ankle [12]. PVNS can occur at any age, although it is most common between the ages of 30 and 50, with a female preponderance of 2:1 [13]. The aim of this study is to remind orthopedic surgeons about the unusual properties of LPVNS located in the knee.

A 39-year-old man entered our clinic with pain and discomfort in his right knee. The pain had persisted for 2 weeks, after a sprain of the right knee while playing soccer. A physical examination revealed mild pain and tenderness in flexion and extension, while the patellar tendon contracted in extension. Lateral and medial McMurray tests were negative. Routine laboratory tests including ESR, CRP, and serum uric acid levels were normal.

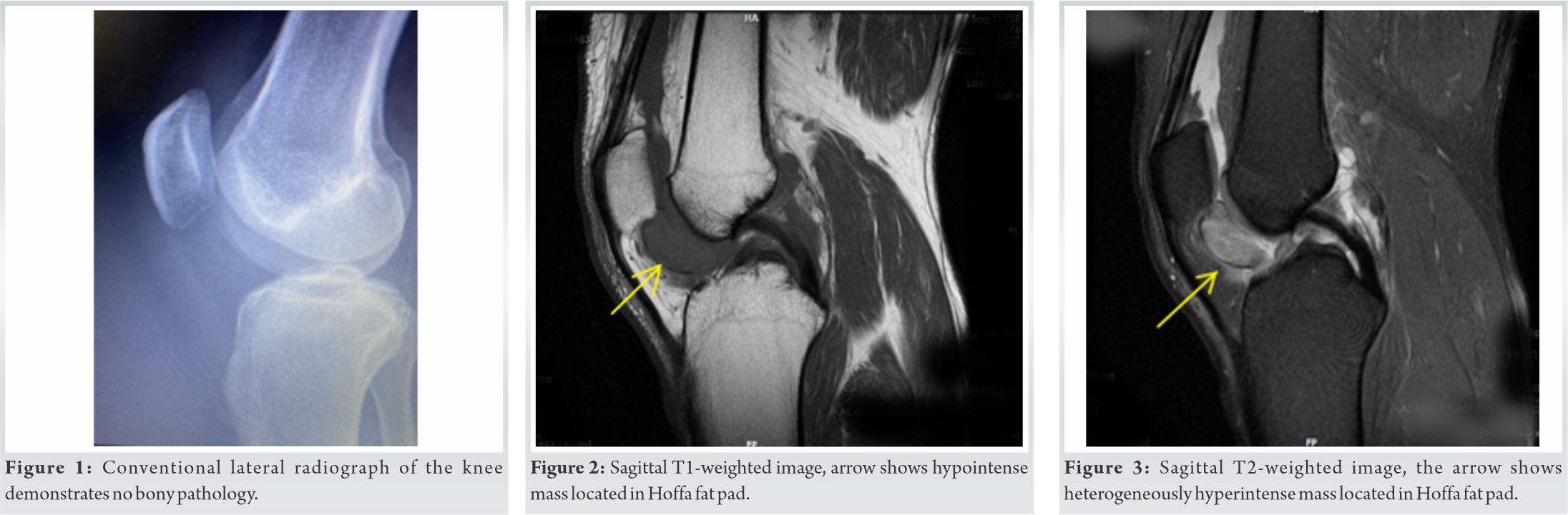

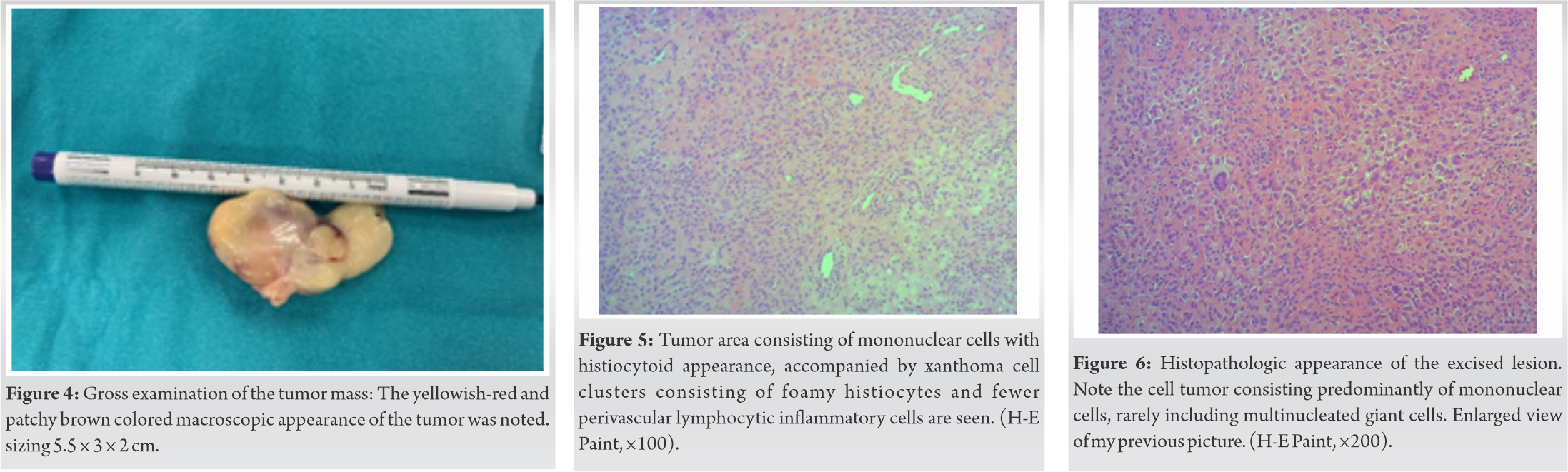

Radiographs showed no bony pathology (Fig. 1). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed an intra-articular mass of 2.7 × 2.1 × 1.3 cm in the infrapatellar region of the knee adjacent to the Hoffa fat pad. The mass was hypointense in the T1 sequence (Fig. 2) and heterogeneously hyperintense in the T2 sequence (Fig. 3), which may be considered a LPVNS. Based on these findings, open surgical excision of the mass was decided. Under spinal anesthesia, the longitudinal midline approach with medial parapatellar arthrotomy was used. The mass was identified in the Hoffa fat pad (Video 1). Excision was carefully performed without penetrating the tumor, and the macroscopic appearance of the tumor was yellowish-red and brown in color (Fig. 4). A histopathologic examination revealed LPVNS (Fig. 5, 6). The patient was pain free 3 weeks after surgery. After a 1 year follow up, no recurrence had been detected.

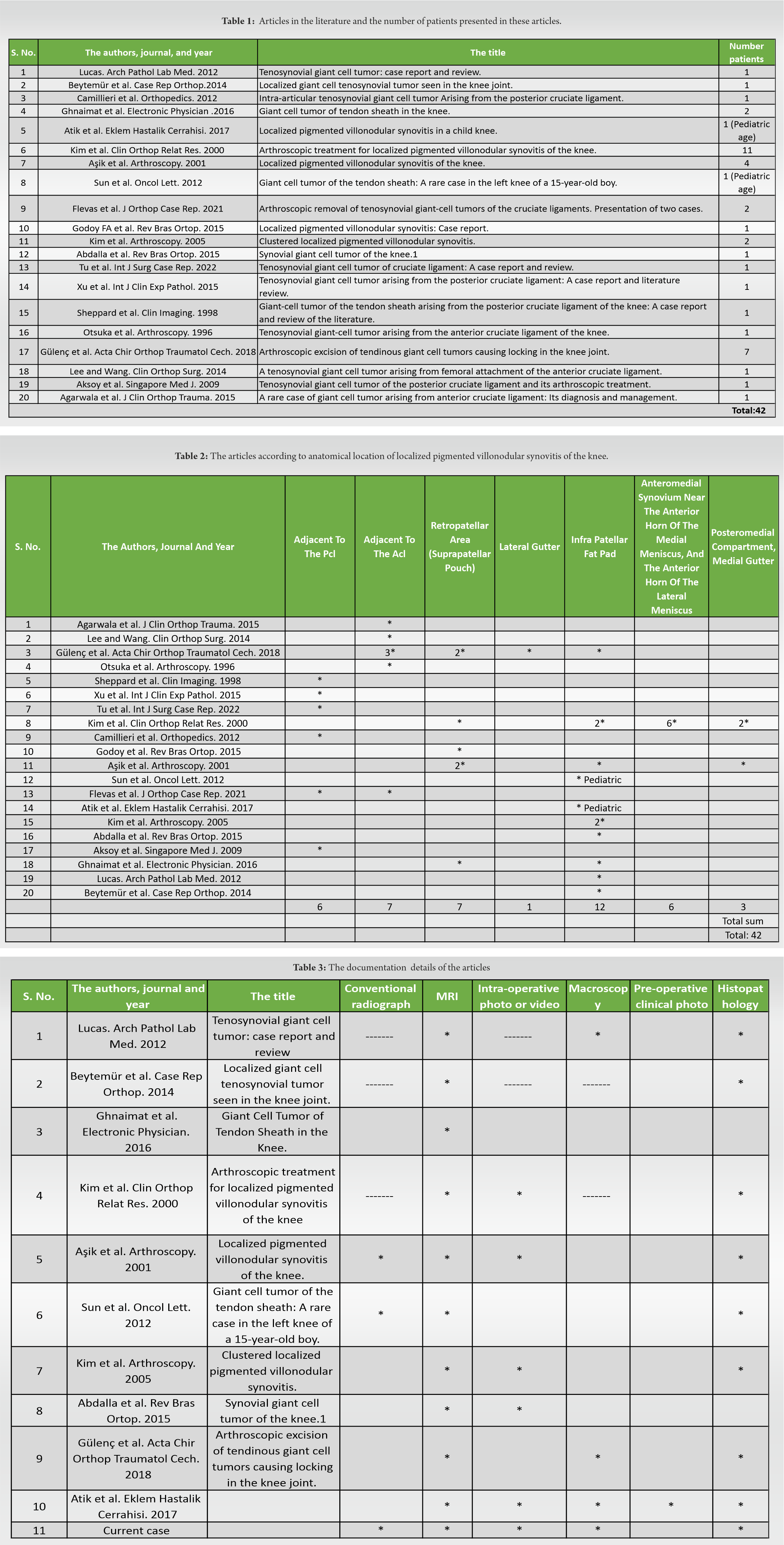

In this case presentation, we described the clinical and radiologic features of LPVNS and explained the rationale for treatment using open excision. A comprehensive literature search of localized tenosynovial giant cell tumor or localized pigmented villonodular synovitis of the knee since 1996 was performed, and 20 articles with 42 cases were found [10, 11, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31] (Table 1). Only ten articles with ten cases involved the infrapatellar fat pads, excluding two pediatric patients [10, 14, 15, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 23, 28] (Table 2). The ten articles were analyzed to compare the quality of the evidence and the didactic features of the articles. The majority of articles in the literature included histopathologic photographs, intraoperative photographs, and pre-operative MRI (Table 3). Rarely, authors reported conventional radiographs or macroscopic photographs of the tumor. Intraoperative video images of the tumor with applied exposure were not used in any article. In this article, we would like to add to the literature a visual teaching tool with a prepared video of photographs and a video of the case. It is still debated whether the treatment of LVPNS should be arthrotomy or arthroscopy. There is no consensus on this issue. Considering the basic principles of tumor surgery, open surgery seems to be more feasible than arthroscopy. This is because it has the advantage of excision of the tumor from the knee without penetrating and possibly seeding to the joint. Although the total recurrence rate of PVNS varied from 7% to 44% [32, 33], one study reported a rate of 18% after arthroscopic treatment of LPVN within a 6–9 month follow-up [34]. The recurrence rate of 18% in a short period also causes us to favor open excision. In addition, the size of these tumors is usually not suitable for arthroscopic excision. In our case, we preferred open resection, because we were concerned that the tumor would not come out in one piece through the arthroscopic portal because of its size, and moreover, if the surgeon preferred a portion-by-portion excision, it would seed and recur.

Even though LPVNS of the knee is an uncommon intra-articular phenomenon, orthopedic surgeons should not overlook this lesion based on imaging findings, and open excision should be regarded as a reliable treatment option.

LPVNS is a rare tumor that rarely affects the knee. However, when it does affect the knee, it is usually localized in the anterior compartment. Awareness and clinical sense are important in diagnosis. Orthopedic surgeons should prefer open excision if the tumor does not appear to come out of the arthroscopic portal in one piece.

References

- 1.Jaffe HL, Lichtenstein L, Sutro CJ. Pigmented villonodular synovitis, bursitis and tenosynovitis. Arch Pathol 1941;31:731-65. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Byers PD, Cotton RE, Deacon OW, Lowy M, Newman PH, Sissons HA, et al. The diagnosis and treatment of pigmented villonodular synovitis. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1968;50:290-305. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Granowitz SP, D’Antonio J, Mankin HL. The pathogenesis and long-term end results of pigmenvillonodular synovitis. Clin Orthop 1976;114:335-51. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reilly KE, Stern PJ and Dale JA. Recurrent giant cell tumors of the tendon sheath. J Hand Surg 1999;24:1298-302. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abdul-Karim FW, El-Naggar AK, Joyce MJ, Makley JT, Carter JR. Diffuse and localized tenosynovial giant cell tumor and pigmented villonodular synovitis: A clinicopathologic and flow cytometric DNA analysis. Hum Pathol 1992;23:729-35. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rao AS, Vigorita VJ. Pigmented villonodular synovitis (giant-cell tumor of the tendon sheath and synovial membrane). A review of eighty-one cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1984;66:76-94. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Flandry F, Hughston JC. Pigmented villonodular synovitis. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1987;69:942-949. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ogilvie-Harris DJ, McLean J, Zarnett ME. Pigmented villonodular synovitis of the knee. The total arthroscopic synovectomy, partial arthroscopic synovectomy, and arthroscopic local excision. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1992;74:119-23. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beguin J, Locker B, Vielpeau C, Souquieres G. Pigmented villonodular synovitis of the knee: Results from 13 cases. Arthroscopy 1989;5:62-4. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim SJ, Shin SJ, Choi NH, Choo ET. Arthroscopic treatment for localized pigmented villonodular synovitis of the knee. Clin Orthop 2000;379:224-30. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Godoy FA, Faustino CA, Meneses CS, Nishi ST, Góes CE, Canto AL. Localized pigmented villonodular synovitis: Case report. Rev Bras Ortop 2015;46:468-71. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fletcher CD, Unni KK, Mertens F, editors. Giant cell tumour of tendon sheath In: World Health Organization Classification of Tumors, Pathology and Genetics of Tumors of Soft Tissue and Bone. Lyon: IARC Press; 2002. p. 110-1. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ushijima M, Hashimoto H, Tsuneyoshi M, Enjoji M. Giant cell tumor of the tendon sheath (nodular tenosynovitis): A study of 207 cases to compare the large joint group with the common digit group. Cancer 1986;57:875-84. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lucas DR. Tenosynovial giant cell tumor: Case report and review. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2012;136:901-6. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beytemür O, Albay C, Tetikkurt US, Oncü M, Baran MA, Cağlar S, et al. Localized giant cell tenosynovial tumor seen in the knee joint. Case Rep Orthop 2014;2014:840243. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Camillieri G, Di Sanzo V, Ferretti M, Calderaro C, Calvisi V. Intra-articular tenosynovial giant cell tumor arising from the posterior cruciate ligament. Orthopedics 2012;35:e1116-8. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ghnaimat M, Alodat M, Aljazazi M, Al-Zaben R, Alshwabkah J. Giant cell tumor of tendon sheath in the knee. Electron Physician 2016;25;8:2807-9. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Atik OŞ, Bozkurt HH, Özcan E, Bahadır B, Uçar M, Öğüt B, et al. Localized pigmented villonodular synovitis in a child knee. Eklem Hastalik Cerrahisi 2017;28:46-9. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aşik M, Erlap L, Altinel L, Cetik O. Localized pigmented villonodular synovitis of the knee. Arthroscopy 2001;17:E23. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sun C, Sheng W, Yu H, Han J. Giant cell tumor of the tendon sheath: A rare case in the left knee of a 15-year-old boy. Oncol Lett 2012;3:718-20. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Flevas DA, Karagiannis AA, Patsea ED, Kontogeorgakos VA, Chouliaras VT. Arthroscopic removal of tenosynovial giant-cell tumors of the cruciate ligaments. presentation of two cases. J Orthop Case Rep 2021;11:23-7. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim RS, Kang JS, Jung JH, Park SW, Park IS, Sun SH. Clustered localized pigmented villonodular synovitis. Arthroscopy 2005;21:761. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Abdalla RJ, Cohen M, Nóbrega J, Forgas A. Synovıal gıant cell tumor of the knee. Rev Bras Ortop. 2015;44:437-40. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tu NV, Quyen NV, Ngoc MH, Trung HP, Nguyen BS, Trung DT. Tenosynovial giant cell tumor of cruciate ligament: A case report and review. Int J Surg Case Rep 2022;91:106771. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xu Z, Mao P, Chen D, Shi D, Dai J, Yao Y, Jiang Q. Tenosynovial giant cell tumor arising from the posterior cruciate ligament: A case report and literature review. Int J Clin Exp Pathol 2015;8:6835-40. [Google Scholar]

- 26.heppard DG, Kim EE, Yasko AW, Ayala A. Giant-cell tumor of the tendon sheath arising from the posterior cruciate ligament of the knee: A case report and review of the literature. Clin Imaging 1998;22:428-30. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Otsuka Y, Mizuta H, Nakamura E, Kudo S, Inoue S, Takagi K. Tenosynovial giant-cell tumor arising from the anterior cruciate ligament of the knee. Arthroscopy 1996;12:496-9. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gülenç B, Kuyucu E, Yalçin S, Çakir A, Bülbül AM. Arthroscopic excision of tendinous giant cell tumors causing locking in the knee joint. Acta Chir Orthop Traumatol Cech 2018;85:109-12. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee JH, Wang SI. A tenosynovial giant cell tumor arising from femoral attachment of the anterior cruciate ligament. Clin Orthop Surg 2014;6:242-4. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Agarwala S, Agrawal P, Moonot P, Sobti A. A rare case of giant cell tumour arising from anterior cruciate ligament: Its diagnosis and management. J Clin Orthop Trauma 2015;6:140-3. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Aksoy B, Ertürer E, Toker S, Seçkin F, Sener B. Tenosynovial giant cell tumour of the posterior cruciate ligament and its arthroscopic treatment. Singapore Med J 2009;50:e204-5. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lowyck H, De Smet L: Recurrence rate of giant cell tumors of the tendon sheath. Eur J Plast Surg 2006;28:385-8. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Al-Qattan MM. Giant cell tumours of tendon sheath: classification and recurrence rate. J Hand Surg Br 2001;26:72-5. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rhee PC, Sassoon AA, Sayeed SA, Stuart MS, Dahm DL. Arthroscopic treatment of localized pigmented villonodular synovitis: Long-term functional results. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ) 2010;39:90-4. [Google Scholar]