After a patellectomy performed to remove a locally aggressive tumor, the tissue gap can be fulfilled with a hybrid augment and potentially restore knee’s extensor apparatus; both in terms of anatomical continuity and functional performances.

Dr. Edoardo Ipponi, Department of Orthopedics and Trauma Surgery, University of Pisa, Pisa, Italy. E-mail: edward.ippo@gmail.com

IntroductionThe extensor apparatus of the knee can be thought of a chain that transmits the muscular strength developed by the quadriceps muscles to the proximal tibia. This complex is essential to allow the extension of the tibia over the femur, being essential to provide knee mobility and stability. In case of lesions which irreparably damage the patella, such as a locally aggressive bone tumor, it is necessary to restore both the apparatus’ anatomical continuity and its strength.

Case ReportA 67-years-old Caucasian woman developed atraumatic swelling and soreness in her left knee. X-rays and MRI images evidenced an osteolytic degeneration of the patella. A diagnosis of Gigant cell tumor of bone was made with a needle biopsy. We performed an en bloc resection of the patella and replaced it with a composite augment made with a polypropylene mesh and a fascia lata allograft. No complication was observed. In her latest follow-up, our patient did not have any extension lag and quadriceps strength was completely restored.

ConclusionThe combination of internal layers of polypropylene surgical mesh and a surface allogenic graft can provide good mechanical performances for patients who underwent patellectomy due to a locally aggressive tumor.

KeywordsPatellectomy, patellar reconstruction, bone tumor, surgical mesh, fascia lata.

The extensor apparatus of the knee is proximally composed of the quadriceps muscles that converge to a central tendon which in its turn inserts on the base of the patella. Distally, the apical end of the same bone is connected to the tibial tuberosity by the patellar ligament connects. This apparatus can be thought of a chain that transmits the muscular strength developed by the quadriceps muscles to the proximal tibia, being passed through the quadriceps tendon, the patella, and the patellar ligament. This complex is essential to allow the extension of the tibia over the femur and its proper functioning is a key factor for the overall active knee mobility. Furthermore, the extensor apparatus also represents a static and dynamic stabilizer for the whole articulation. For those reasons, lesions of those structures often lead to a sub-total or even complete functional deficit of the knee, with extension deficits and inability to maintain an upright position [1].

In modern days’ orthopedic practice, reconstruction of the knee extensor apparatus represents a point of interest in some of the most important branches of surgery, such as traumatology and arthroplasty [2, 3, 4, 5]. Non-operative approach is associated with poor functional outcomes; therefore, surgery is often the only viable treatment. Many reconstructive procedures have been described in the literature to this date, Moreover, the choice of one over another depends on several variables. When a decision must be made, surgeons should focus not only on the cause and the size of the lesion itself, but also on patient’s global clinical picture and their post-operative functional requests. Surgery is often complex and often it becomes even more challenging in orthopedic oncology [6]. In fact, in cases who suffer from a locally aggressive tumor, resection must be as wide as possible to minimize the risk of local recurrence of the disease. This means the sacrifice of the involved tissue, and, when the knee extensor apparatus is involved, an inevitable break in its continuity. Therefore, once resection has been carried out, surgeons must perform a reconstruction with large and strong grafts, able to fulfills wide gaps but also tolerate and transmit the high energies generated by the quadriceps muscle.

We report one case of locally aggressive tumor of the patella treated with massive resection of the knee extensor apparatus and consequent reconstruction with a fascia lata allograft reinforced by a surgical mesh.

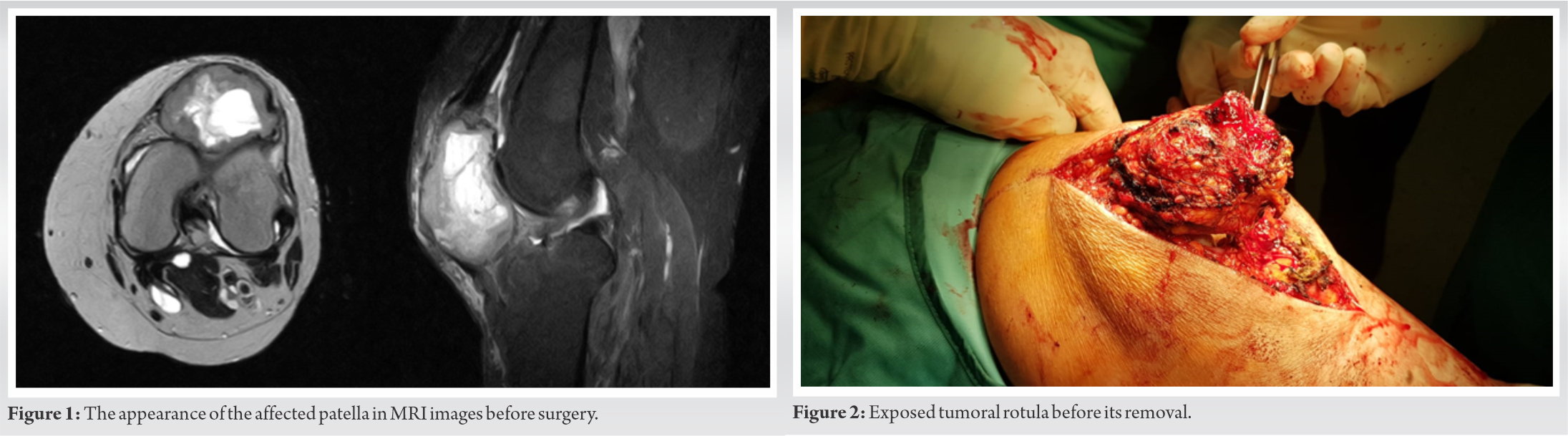

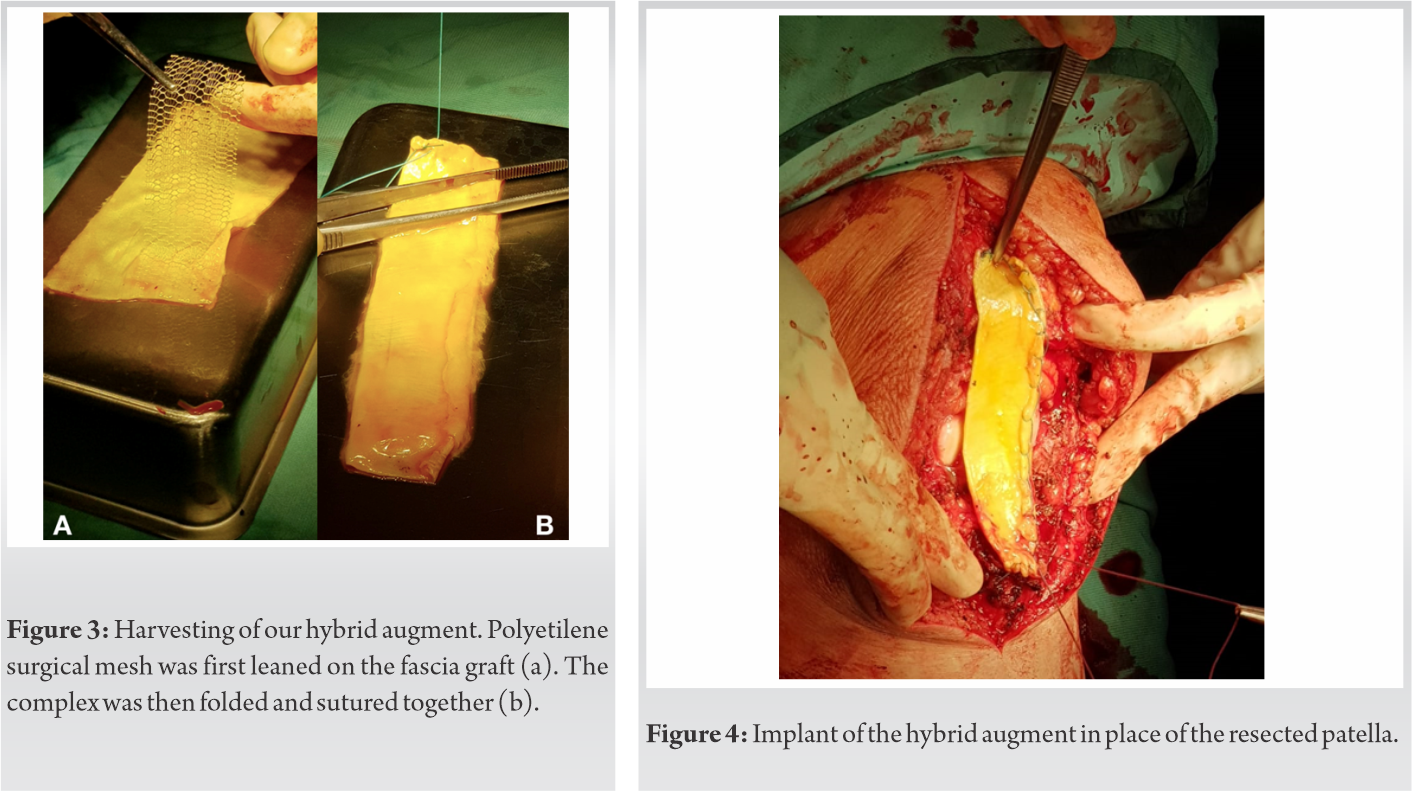

This report has been performed in accordance with the ethical standards laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments. The patient gave written consent. Our case is a 67-year-old woman who had been complaining of increasing anterior knee pain for over a year. Soreness was present during both day and night hours, increasing its intensity after prolonged and intense physical activities. When the patient first came to our attention, her rotula was deformed, enlarged, and painful to palpation. Active flexion-extension range of motion was allowed for 10–75°. Passive mobilization over the aforementioned range caused her intense pain to the anterior knee. CT scans and MRI images reported an expansive solid lesion arising from the left patella (Fig. 1). Subsequent bone scans using bisphosphonates radiolabeled with technetium-99m testified localized marker uptake in the patellar region. In light of the imaging evidences, a CT-guided needle biopsy was performed to allow histological diagnosis. Tissue samples were subjected to microscopical and immunohistochemical evaluations which made a diagnosis of Giant cell tumor of the bone (GCTB). As a first step, we made a pre-operative planning based on MRI scans to assess the width of the gap left after resection and thereby estimate the correct size of the augments, we were going to implant. In the operative room, the patient was positioned supine on the surgical table. A pneumatic tourniquet was set at the limb root and activated before skin incision. We performed a direct longitudinal approach to the anterior knee and centered on the patella. The skin incision was extended for about 20 cm to allow a complete exposure of the bone and its surrounding tissues. Once on the bone layer, we identified the patella which was significantly deformed, since its anterior surface appeared rounder and inhomogeneous (Fig. 2). Patella was then separated from the quadriceps tendon, the patellar ligament, and the patellar retinacula, achieving an en block resection. The affected bone was removed alongside a thin layer of soft tissues that appeared macroscopically free of disease, to get wide resection margins. Once resected, Patella was delivered to our Pathological Anathomy division which confirmed the diagnosis of GCTB. Before the beginning of the reconstructive phase, we made an accurate inspection of the tissues surrounding the resection, included the underlying femoral and tibial surfaces, without finding any suspect lesion.

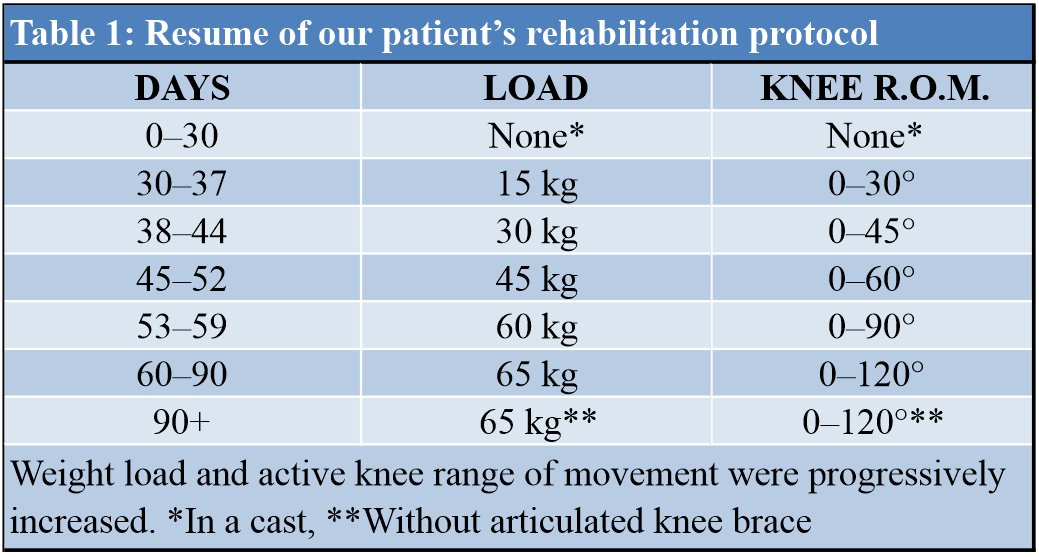

Meanwhile, on a parallel surgical table, we prepared our implant. A 12 × 6 cm fascia lata allograft was spread on a hard flat surface. A stripe of 11 × 4 cm Dipromed surgical mesh was set on the fascia and folded in half on its minor axis (Fig. 3a). The fascia lata allograft itself was then folded to wrap the surgical mesh (Fig. 3b). Once we overleyed the two longest sides of the fascia one to the other, the complex was closed with continuous anchored sutures. The result was a hybrid augment of 12 × 3 cm made of an internal polypropylene layer covered by a surface of bio-integrable fascia lata. Once the harvesting was completed, the implant was set in place of the removed patella and secured to both the quadriceps tendon and the patellar ligament with fiberwire sutures (Fig. 4).

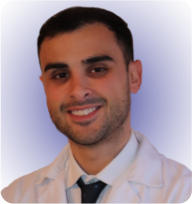

Finally, the endurance of the implant was tested, showing good intraoperative results in terms of resistance to mechanical stress. Right after surgery, the knee has been immobilized in extension inside a leg cast that was maintained for 30 days. During those 30 days, weight load was not allowed. One month after surgery, the cast was removed and replaced by an articulated knee brace. Allowed range of motion and weight load on the affected limb was progressively increased through the following weeks, as reported in (Table 1).

Three months after surgery, the knee had an active painless range of motion of 0–120°, extension strength was restored and the limb could successfully support patient’s full weight of 65 kg. Those outcomes allowed her to come back to her work and to her activities of daily living. At last follow-up, 14 months after surgery, functional outcomes were steady, without any extension lag and with an active flection of 120°. Flexion and extension strength were comparable to the ones of the contralateral knee. No major local or systemic complications occurred postoperatively. The patient showed satisfaction for the functional results of our treatment.

Reconstruction after patellar resection is a challenge even for the most experienced orthopedic surgeons. In orthopedic oncology, resection must be carried out with wide margins, with the aim to eradicate the tumor from the site and reduce the risk of local recurrence [6]. Unfortunately, this demand is at odds with the necessities of the following reconstruction. Wider resections mean larger tissue defects and thereby make it tougher to restore the integrity of the knee extensor apparatus. Furthermore, the reconstructed structure should not only be long enough to link the quadriceps muscles to the tibial tuberosity, but also has to be strong enough to resist to the traction forces of the quadriceps and transmit them to the tibia. In fact, it is mandatory to replace the native extensor apparatus with a new one that associates length, strength, and stability [7]. Several reconstructive solutions have been described through the last decades, including synthetic augments, muscular flaps, autografts, and allografts [7, 8, 9]. All of them have their pros and their cons. Non-biological implants generally have good mechanical properties, but in they do not allow biological integration and as a consequence their performances tend to decrease through the years. On the other hand, biological reconstruction can be integrated within patients’ receiving site, leading to a better functional horizon on the mid- and long-term scenario. Those better biological properties, anyway, do not come without a cost: Both allografts and autograft are limited in number and call for longer surgical times, especially the latter which also requires a second surgical field and the sacrifice of a donor site [10]. In this article, we present the combination of synthetic mesh and fascia lata allograft as a possible meeting point for biological and synthetical reconstructions after patellectomy due to a locally aggressive tumor. Fascia lata was chosen in consideration of its combination of length, tensile strength, and stiffness. This source in particular is among the longest and the more elastic grafts nowadays available [11]. Our fascia lata, folded to be reinforced and to surround the mesh, was thought to give a contribution in terms of mechanical resistance, but also to allow a good and fast bio-integration. On a microbiological point of view, it represented a biological scaffold that could be successfully colonized by the cells of the host herself, making it a proper and biologically active part of patient’s body in the long-term period [12]. The polypropylene surgical mesh set in the inner portion of the implant, for its part, was thought to provide further reinforcement increasing the entire complex’s tensile strength. Especially in the 1st weeks and months, before complete integration of the fascia lata could be pursued, an important share of the forces passing through the implant was borne by the synthetic mesh. Furthermore, woven polypropylene decrease the risk of loosening or excessive elongation to which fascia lata alone would be prone when facing prolonged and massive bidimensional strength [13].

Many surgical procedures have been described to perform a reconstruction after patellectomy. Our outcomes suggest that the combination of internal layers of polypropylene surgical mesh and a surface allogenic graft can provide good mechanical performances for patients who underwent patellectomy due to a locally aggressive tumor. This reconstructive approach should, therefore, be taken into consideration among the other most common surgical techniques when oncologic surgeons are called to perform a reconstruction of the knee extensor apparatus.

After a patellectomy performed to remove a locally aggressive tumor, the tissue gap can be fulfilled with an hybrid augment and potentially restore knee’s extensor apparatus; both in terms of anatomical continuity and functional performances.

References

- 1.Dwek JR, Chung CB. The patellar extensor apparatus of the knee. Pediatr Radiol 2008;38:925-35. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Elhessy AH, Alrabai HM, Eltayeby HH, Gesheff MG, Conway JD. Chronic quadriceps tendon rupture reconstruction with sartorius muscle transfer: A report of five cases. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open 2021;9:e3785. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Welle K, Hackenberg RK, Kabir K, Habicht I, Wirtz DC, Kohlhof H. Reconstruction of the extensor apparatus with advanced structural defects in knee revision arthroplasty. Oper Orthop Traumatol 2021;34:129-40. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Deans J, Scuderi GR. Classification and management of periprosthetic patella fractures. Orthop Clin North Am 2021;52:347-55. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Puerta-GarciaSandoval P, Lizaur-Utrilla A, Trigueros-Rentero MA, Perez-Aznar A, Alonso-Montero C, Lopez-Prats FA. Successful mid-to long-term outcome after reconstruction of the extensor apparatus using proximal tibia-patellar tendon composite allograft. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2021;29:982-7. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mattei JC, Curvale G, Rochwerger A. Surgery in around the knee bone tumors. Bull Cancer 2014;101:571-9. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Müller DA, Beltrami G, Scoccianti G, Cuomo P, Totti F, Capanna R. Allograft reconstruction of the extensor mechanism after resection of soft tissue sarcoma. Adv Orthop 2018;2018:6275861. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang J, Zhou Y, Wang YT, Min L, Zhang YQ, Lu MX, et al. Three-dimensional-printed custom-made patellar endoprosthesis for recurrent giant cell tumor of the patella: A case report and review of the literature. World J Clin Cases 2021;9:2524-32. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Malhotra R, Sharma L, Kumar V, Nataraj AR. Giant cell tumor of the patella and its management using a patella, patellar tendon, and tibial tubercle allograft. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2010;18:167-9. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smith PA, Stannard JP, Bozynski CC, Kuroki K, Cook CR, Cook JL. Patellar bone-tendon-bone autografts versus quadriceps tendon allograft with synthetic augmentation in a canine model. J Knee Surg 2020;33:1256-66. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pukšec M, Semenski D, Ježek D, Brnčić M, Karlović S, Jakovčević A, et al. Biomechanical comparison of the temporalis muscle fascia, the fascia lata, and the dura mater. J Neurol Surg B Skull Base 2019;80:23-30. [Google Scholar]

- 12.De Girolamo L, Ragni E, Cucchiarini M, Van Bergen CJ, Hunziker EB, Chubinskaya S. Cells, soluble factors and matrix harmonically play the concert of allograft integration. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2019;27:1717-25. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baylón K, Rodríguez-Camarillo P, Elías-Zúñiga A, Díaz-Elizondo JA, Gilkerson R, Lozano K. Past, present and future of surgical meshes: A review. Membranes (Basel) 2017;7:47. [Google Scholar]