Abnormal presentation of Hydatid disease and the challenges in diagnosis and treatment.

Dr. Nirvin Paul, Department of Trauma Surgery, All India Institute of Medical Science, Rishikesh - 249 203, Uttarakhand, India. E-mail: drnirvinpaul@gmail.com

Introduction: Osseous hydatidosis is a rare orthopedic condition. Osseous hydatidosis leading to chronic osteomyelitis is rarer with very few articles published on it. This presents a challenge in diagnosis and treatment. Here, we report a patient with chronic osteomyelitis secondary to Echinococcal infection.

Case Report: A 30-year-old lady with fracture left femur operated elsewhere presented with a draining sinus. She underwent a debridement and sequestrectomy. The condition was quiescent until 4 years later when symptoms recurred. She again underwent debridement, sequestrectomy, and saucerisation. The biopsy showed hydatid cyst.

Conclusion: The diagnosis and treatment are challenging. The chances of recurrence are very high. Multimodality approach is recommended.

Keywords: Osseous hydatidosis, chronic osteomyelitis, hydatid cyst.

Echinococcosis is a zoonotic infection caused by adult or larval (metacestode) stages of cestodes belonging to the genus Echinococcus and the family Taeniidae. At present, four species of Echinococcus are recognized, namely, Echinococcus granulosus, Echinococcus multilocularis, E. oligarthrus, and Echinococcus vogeli. Of these, E. granulosus is the most common cause of infection in humans. Echinococcosis is an important zoonosis and has a worldwide geographical distribution. It is most prevalent in Eurasia, Africa, Australia, and South America. Within the endemic countries, the distribution varies significantly. The annual incidence in India varies from 1 to 200/100,000 people [1]. High prevalence has been reported in Jammu and Kashmir, Andhra Pradesh, Tamil Nadu and Central India [2, 3]. The definitive hosts are canines that excrete the eggs in feces. Eggs are ingested orally and cysts develop in the intermediate hosts such as sheep, cattle, humans and camels for E. granulosus, and rodents for E. multilocularis. E.granulosuslives for 5–20 months in the jejunum of canines and has three proglottids–Immature, mature, and gravid. The gravid segment releases eggs and when ingested by humans, the embryo penetrates the intestinal mucosa and enters the portal circulation and is carried to various organs especially liver and lung. Larvae develop into fluid filled unilocular cysts which consist of external membrane and inner germinal layer. Daughter cysts develop from the germinal layer as do germinating cystic structures called brood capsules. New larvae called protoscolices develop inside brood capsules. The cyst expands slowly over years [4]. Hydatid cysts are common in the liver (59–75%) and lungs 27%). Kidneys (3%) and brain (1–2%) are rarely involved. The incidence of hydatid cysts in bone is 0.5–2.5%. Of this, 50% occurs in the spine followed by pelvis and hip. Other regions known to be affected are the femur, tibia, fibula, ribs, scapula, clavicle, and tarsal bones. Osseous hydatidosis is considered a very severe and recurrent complication of hydatidosis and can be very invasive and destructive requiring extensive resection and prosthetic replacement [5].

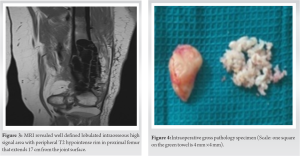

A 30-year-old housewife with history of seizure disorder presented in 2010 with history of fall 5 years earlier when she had sustained a fracture of the left distal femur. She was managed elsewhere with upper tibial pin traction for 1 month following which she underwent intramedullary nailing. Six months later, she developed pain, swelling, and a discharging sinus at the left distal thigh. She was managed elsewhere conservatively for 1 year after which the implant was removed. Later discharge persisted. Debridement was done at the same center and she received antituberculous treatment for 18 months (Fig. 1).

E.granulosus infection is a zoonosis with a worldwide distribution. Hydatid cysts are common in the liver (59–75%) and lungs (27%). Kidneys (3%) and brain (1–2%) are rarely involved. Primary localization of the disease to the musculoskeletal system is very rare. It most commonly affects the spine and extraspinal involvement is rare. It is associated with slow growth and mimics a malignant lesion. Other differentials of tuberculosis and fungal infections should be considered. It can lie dormant for as long as 40 years and most cases of osseous hydatidosis have been described only in adults. Osseous hydatidosis can be locally invasive and can destroy bone. Growth begins in the metaphyseal region and gives rise to multilocular cysts causing scalloping of cortex but with little expansion, sclerosis, or periosteal reaction. Diagnosis is difficult and the clinical suspicion is low. It is better to diagnose preoperatively as it can cause local recurrence and anaphylaxis if it ruptures. However, pre-operative diagnosis is a challenge as there are no specific tests for osseous hydatidosis. Serological diagnosis by ELISA is positive in osseous hydatidosis but is negative in liver and lung involvement. Serology alone is not adequate and is not an accurate test to diagnose. Histopathological examination is important in clinching diagnosis. Plain radiographs are not very sensitive in diagnosis and CT and MRI have a better diagnostic potential. Well-defined osteolytic lesion with bone expansion, cortical thinning and destruction, sclerosis, honeycomb appearance, and extension to adjacent soft tissue is appreciated on a computed tomography. “Water lily” sign where the germinative membrane detached from pericyst seen on MRI is considered pathognomonic for osseous hydatidosis [7]. Treatment is a major challenge due to difficulty in eradication and high rates of recurrence. Scolicides do not kill all daughter cysts and so recurrence rates are high. Alldred and Nishbet in 1964 suggested en bloc resection for lesions in the appendicular skeleton and a more conservative approach for the axial skeleton [8]. Booz advocated thorough curettage to remove macroscopic cysts and chemical sterilization of scolices with formalin, 0.5% silver nitrate or hypertonic saline and autologous bone graft for the defect [9, 10]. Yildiz et al. in 2001 proposed curettage, povidone iodine swabbing and filling of the defect with polymethylmethacrylate. Surgery is considered by some authors as a palliative measure as long-term survival in patients is possible but morbidity is high [11]. “Chemotherapy with benzimidazoles, particularly mebendazole and albendazole, has been used for the treatment of human echinococcosis since 1974, when Heath and Chevis first reported that the benzimidazole derivative mebendazole could kill the germinal membrane of echinococcus in mice by limiting glucose uptake” [12]. Albendazole was found to be better than Mebendazole due to better absorption and penetration and is the most common drug used postoperatively. Li et al. proposed Praziquental for eradication of young cysts but not mature cysts [13]. Yasway showed pre-operative combination of albendazole and praziquental led to significant reduction in number of cysts [14]. Luder et al. found that cimetidine improves bioavailability of benzimidazoles. Del Estal et al. suggested a combination of albendazole and sodium taurocholate for increasing bioavailability and Jung et al. showed that dexamethasone increases bioavailability by 50%. As recurrence rates are high, radical excision is ideal. Herrera et al. claim that hydatid disease affecting hip and pelvis is the most difficult to treat. Obeidat et al. suggested aggressive debridement, gentamicin beads, and bone graft to fill the defect in cases of hydatid disease causing osteomyelitis [15]. Total excision and reconstruction with megaprosthesis are the only alternatives to amputation to effectively treat osseous hydatidosis.

Echinococcal infection of bone is a rare entity and chronic osteomyelitis resulting from osseous hydatidosis is a diagnostic challenge. Diagnosis is difficult due to lack of proper investigative modalities and low clinical suspicion, often requiring histopathological evidence. The treatment is a challenge in itself due to difficulty in eradication and high chances of recurrence.

The diagnosis and treatment of osseous hydatidosis are challenging. The chances of recurrence are very high. Multimodality approach is recommended.

References

- 1.Eckert J, Schantz PM, Gasser RB, Torgerson PR, Bessonov AS, Movsessian SO, et al. Geographic distribution and prevalence of Echinococcus granulosus. In: Eckert J, Gemmell MA, Meslin FX, Pawłowski ZS, editors. WHO/OIE Manual on Echinococcosis in Humans and Animals: A Public Health Problem of Global Concern. France: Office International des Epizooties; 2001. p. 103. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Akhter J, Khanam N, Rao S. Clinico epidemiological profile of hydatid diseases in central India, a retrospective and prospective study. Int J Biol Med Res 2011;2:603-6. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Parija SC, Rao RS, Badrinath S, Sengupta DN. Hydatid disease in Pondicherry. J Trop Med Hyg 1983;86:113-5. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Longo DL, Kasper DL, Jameson JL, Fauci AS, Hauser AL, Loscalzo J. Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine. 18th ed., Vol. 1. New York: McGraw-Hill Professional; 2011. p. 1762-3. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beggs I. The radiology of hydatid disease. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1985;145:639-48. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Song XH, Ding LW, Wen H. Bone hydatid disease. Postgrad Med J 2007;83:536-42. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Comert RB, Aydingoz U, Ucaner A, Arikan M. Water-lily sign on MR imaging of primary intramuscular hydatidosis of sartorius muscle. Skeletal Radiol 2003;32:420-3. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alldred AJ, Nisbet NW. The management of hydatid disease of bone and joint. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1964;46:260-7. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Booz MK. The management of hydatid disease of bone and joint. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1972;54:698-709. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hooper J, McLean I. Hydatid disease of the femur. Report of a case. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1977;59:974-6. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yildiz Y, Bayrakci K, Altay M, Saglik Y. The use of polymethylmethacrylate in the management of hydatid disease of bone. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2001;83:1005-8. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heath DD, Chevis RA. Mebendazole and hydatid cysts. Lancet 1974;2:218-9. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li J, Zhou PF, Yang WG. Investigation of the treatment for liver alveolar hydatidosis. Acta Academice Medicine Xinjiang 1993;16:238. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yasawy MI, Al Karawi MA, Mohamed AR. Combination of praziquantel and albendazole in the treatment of hydatid disease. Trop Med Parasitol 1993;44:192-4. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Obeidat MM, Mustafa Z. Treatment of chronic osteomyelitis secondary to hydatid disease of bone using gentamycin beads. Int J Low Extrem Wounds 2012;11:171-3. [Google Scholar]