Meticulous management of Morel-Lavallee lesion and underlying bony injury is very important to achieve good clinical outcome.

Address of Correspondence: Dr. Pranay Kondewar, Department of Orthopaedics Grant Government Medical College and JJ Hospital, Mumbai - 400 008, Maharashtra, India. E-mail: pranaypk1@gmail.com

Introduction: Morel-Lavallee lesion is a closed degloving soft-tissue injury which occurs as a result of acute traumatic separation of skin and subcutaneous tissue from the underlying fascia and muscle layer. The most common sites include thigh (peritrochanteric region), abdomen, scapula, and paraspinal area. Early diagnosis and management of the lesion is essential so as to prevent complications such as infections or extensive skin necrosis. The management options include conservative or operative depends on extent, location of lesion, and duration since injury. For the management of underlying fracture, one should take into the consideration, the soft tissue compromises which can occur if lesion is large at presentation and plan accordingly for either primary definitive fixation or staged surgeries as necessary.

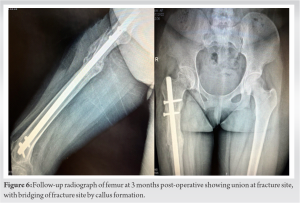

Case Report: A 25-year-old female patient presented with pain and swelling over the anterolateral aspect of the right thigh after a traumatic road traffic accident 2 days back. On radiological investigation, there was subtrochanteric femur fracture with a butterfly fragment. The patient also had Morel-Lavallee lesion on local ultrasound. Emergency management was done for Morel-Lavallee lesion in the form of percutaneous drainage and compression bandage; fixation was done in the form of external fixator. The wound progressed into complete skin necrosis so external fixator was removed and thorough wound debridement was done. Fracture stabilized with four TENS nails (titanium elastic nail). Removal of the TENS nail and exchange nailing in the form of intramedullary interlocking nail was performed after complete soft-tissue healing. Bony union seen at the fracture site clinically and radiologically at 3-month follow-up.

Conclusion: :Initial screening of lesion is very important at time of presentation. Early definitive fixation should not be done if the lesion is large and one should fix the bone once the lesion is resolved.

Keywords: Morel-Lavallee lesion, subtrochanteric femur fracture, soft-tissue injury, fat necrosis, hypertrophic non-union, exchange nailing.

Morel-Lavallee lesion is a closed degloving soft-tissue injury which occurs as a result of acute traumatic separation of skin and subcutaneous tissue from the underlying fascia and muscle layer. This condition was first described by French physician Maurice Morel-Lavallée in the year 1853 [1]. After a traumatic event, there is a separation of tissue between fat layer and muscle layer causing extensive shearing of the capillaries and lymphatics, leading to accumulation of blood between these layers along with serosanguinous fluid and necrotic fat. There is arterial plexus superficial to the deep fascia of the lower extremity. Its supply is derived from perforating musculocutaneous and fasciocutaneous vessels as they pierce the deep fascia, in this layer, they get oriented in longitudinal fashion to supply skin and fat layer above with limited axiality in the network [2]. The most common sites include thigh (peritrochanteric region), abdomen, scapula, and paraspinal area. One of the most commonly involved regions is the greater trochanter, accounting for more than 60% of the cases [3, 4]. Early diagnosis and management of the lesion is essential so as to prevent complications such as infections or extensive skin necrosis. The management options include conservative or operative depends on extent, location of lesion, and duration since injury. In longstanding cases, these lesions may subsequently enlarge and become painful, leading to misdiagnosis of soft-tissue tumor [5].

A 25-year-old female patient presented with pain and swelling over the anterolateral aspect of the right thigh after a traumatic road traffic accident 2 days back. On examination, there was a boggy, tender, and fluctuating swelling of size 10 × 5 cm over the lateral aspect of thigh, along with contusion of skin over swelling also there was a puncture wound over the thigh. On radiological investigation, there was subtrochanteric femur fracture with a butterfly fragment (Fig. 1). The patient was suspected to have Morel-Lavallee lesion so local ultrasound was done and found to have collection of size 15 × 10 cm between muscle layer and subcutaneous fat. Emergency management was done for Morel-Lavallee lesion in the form of percutaneous drainage and compression bandage; gentamicin is instilled locally after the drainage to avoid infection. Fluid isolated from drained area was sent for microbiological investigation. Imperial antibiotics started. Preliminary fixation was done in the form of external fixator at the time of drainage of hematoma. The wound progressed over the period of next 2 weeks and superficial skin started to get necrosed due to underlying devascularization and infection, which caused complete skin necrosis (Fig. 2).

Morel-Lavallee lesion poses a dilemma to surgeons about when to operate immediately and when conservative management can be done. For this, no fixed guidelines exist in literature but various authors have given management options based on extent of soft-tissue injury and presence of bony involvement. As suggested by Ronceray in 1976, if the area of detachment is small, the less number of lymphatic and blood vessels will drain in the region of injury. In those cases, complete resolution of the mass is seen with the application of a compression bandage or after percutaneous drainage. If the area of detachment is large and after initial trauma, then a capsule is seen to develop around the lesion, which contributes to the establishment of the fluid mass. In such cases, surgical treatment is mandatory [6]. Ultrasonography features are in accordance with age of hematoma. The lesions appear as a focal anechoic to isoechoic complex collection located superficial to the muscle plane and deep to hypodermis. It may contain fat globules that appear as hyperechoic nodules. Computerized tomography scan of a Morel‐Lavallée lesion shows fluid‐fluid level resulting from sedimentation of blood components and may have capsule surrounding the lesion. Magnetic resonance imaging is the imaging modality of choice. Signal characteristics of the lesion depend on chronicity and internal contents. The lesions are often homogeneously hypointense on T1W sequences and hyperintense on T2W sequences, may resemble a simple fluid collection. A T1W, T2W hypointense peripheral ring representing hemosiderin and fibrous tissue may also be seen in chronic cases [7]. Mellado and Bencardino proposed a classification based on the shape of lesion, signal characteristics, enhancement, and the presence or absence of a capsule. Six types of lesions were described [8]. Diagnosis and early management of Morel-Lavallee lesion is important as they may pose as an independent risk factor for surgical site infection. Management options include conservative management by percutaneous drainage and compression bandage with antibiotics cover [9]. In cases with multiple effusions and infection, incision and drainage are necessary, especially in lesions with a volume of more than 50 ml. Sclerodesis treatment is successful in Morel-Lavallee lesions where percutaneous aspiration fails. The common agents include doxycycline, erythromycin, vancomycin, tetracycline, bleomycin, absolute ethanol, and talc. These agents act by cellular destruction within the periphery of the lesion, which later on results in fibrosis. Overall efficacy of sclerosing agents in managing Morel-Lavallée lesions has been reported as 95.7% [10, 11]. The majority of these lesions require open debridement with excision of the pseudo capsule in chronic cases. The goal in managing Morel-Lavallee lesions is the closure of dead space which can be achieved in various ways, including fibrin sealant, quilting sutures, and low suction drains. A single longitudinal incision or multiple small incisions can be used for the open drainage in cases where the overlying skin is viable. If the condition of skin overlying the lesion is necrotic, then dead tissue needs to be debrided, followed by reconstruction of the soft-tissue envelope [12]. In a study by Tejwani et al., 27 knees in 24 players were identified from injury database as having sustained a Morel-Lavallee lesion between 1993 and 2006. Their charts were retrospectively reviewed. Most cases were treated with single or multiple aspirations and compression bandage. In three cases, the Morel-Lavallee lesion was successfully treated with doxycycline sclerodesis after three aspirations failed to resolve the recurrent fluid collections [13]. Most of the cases does not progress into severe soft-tissue necrosis but in our case, initial impact of injury had caused extensive loss of blood supply and skin necrosis because of which fracture was not able to be managed definitively at initial presentation and leads to hypertrophic non-union because of instability at fracture site which healed well on definitive fixation in the form of exchange nailing using intramedullary interlock nail.

Initial screening of lesion is very important at time of presentation and should be addressed as early as possible to avoid complications. Early definitive fixation should not be done if the lesion is large and one should fix the bone once the lesion is resolved.

Early diagnosis of Morel-Lavallee lesion clinically and with the help of radiological investigation is important to plan the management of underlying bony injury. Failure of which can lead to complications such as post-operative infection and non-union. Consensus among surgeons is to treat these injuries in staged manner with priority given to recovery of soft-tissue injury and primary bony stability.

References

- 1.Nair AV, Nazar P, Sekhar R, Ramachandran P, Moorthy S. Morel-Lavallée lesion: A closed degloving injury that requires real attention. Indian J Radiol Imaging 2014;24:288-90. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kottmeier SA, Wilson SC, Born CT, Hanks GA, Iannacone WM, DeLong WG. Surgical management of soft tissue lesions associated with pelvic ring injury. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1996;329:46-53. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bonilla-Yoon I, Masih S, Patel DB, White EA, Levine BD, Chow K, et al. The morel-lavallee lesion: Pathophysiology, clinical presentation, imaging features, and treatment options. Emerg Radiol 2014;21:35-43. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Diviti S, Gupta N, Hooda K, Sharma K, Lo L. Morel-lavallee lesions-review of pathophysiology, clinical findings, imaging findings and management. J Clin Diagn Res 2017;11:TE01-4. [Google Scholar]

- 5.McKenzie GA, Niederhauser BD, Collins MS, Howe BM. CT characteristics of Morel-lavallee lesions: An under-recognized but significant finding in acute trauma imaging. Skeletal Radiol 2016;45:1053-60. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ronceray J. Drainage actif, par resection aponevrotique partielle, des épan-chements de morel-lavallee. SO Nouv Presse Med 1976;5:1305-6. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gilbert BC, Bui-Mansfield LT, Dejong S. MRI of a morel-lavallee lesion. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2004;182:1347-8. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mallado JM, Bencardino JT. Morel‐lavellee lesion: Review with emphasis on MR imaging. Magn Reson Imaging Clin N Am 2005;13:775‐82. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harma A, Inan M, Ertem K. The morel-lavallee lesion: A conservative approach to closed degloving injuries. Acta Orthop Traumatol Turc 2004;38:270-3. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Agrawal U, Tiwari V. Morel Lavallee Lesion. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Isaacson AJ, Stavas JM. Image-guided drainage and sclerodesis of a morel-lavallee lesion. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2013;24:605-6. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carlson DA, Simmons J, Sando W, Weber T, Clements B. Morel-lavalée lesions treated with debridement and meticulous dead space closure: Surgical technique. J Orthop Trauma 2007;21:140-4. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tejwani SG, Cohen SB, Bradley JP. Management of morel-lavallee lesion of the knee: Twenty-seven cases in the national football league. Am J Sports Med 2007;35:1162-7. [Google Scholar]