Osteofibrous dysplasia of the clavicle is an uncommon entity and can be managed with intravenous bisphosphonates therapy with a good outcome.

Dr. R Preethiv, Department of Orthopaedics, KIMS, Bhubaneswar, Odisha, India. E-mail: preethivr96@gmail.com

Introduction: Osteofibrous dysplasia is a fibro-osseous benign lesion of childhood and infancy that are commonly seen in the anterior shin of the tibia. Osteofibrous dysplasia in the clavicle is rare and in this study, we reported a case of osteofibrous dysplasia arising in the midshaft of the clavicle.

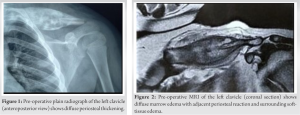

Case Report: An 11-year boy presented with complaints of pain and swelling over his left clavicle and was unable to do overhead abduction following a fall while playing 2 years back. Initially, the patient was diagnosed with a left clavicle fracture and was treated conservatively. The pain subsided after 3 months. The patient had re-injury after 6 months, following which pain and swelling of the left clavicle were gradually progressive. On examination, there was a diffuse swelling extending from the medial end to the lateral end of the left clavicle, which was tender, and bony-hard in consistency. The range of movements of the left shoulder was painful and terminally limited. A percutaneous core-needle biopsy was done, suggestive of a benign fibro-osseous lesion. An open biopsy was done from the tumor-normal bone junction, and caseous materials were found inside the medullary canal, the microscopic finding shows fibroblastic proliferation and osteoblastic proliferation laying down the woven bone. We treated the case with intravenous pamidronate injection in 6 months intervals for 2 years. The patient improved symptomatically achieving a full range of movements of the affected shoulder with good radiological consideration of the lesion.

Conclusion: Osteofibrous dysplasia is uncommonly seen in the clavicle, and if it is seen, it may mimic osteomyelitis clinically. It should be differentiated from other lesions by radiological, histopathological, and immunohistochemistry findings

Keywords: Osteofibrous dysplasia, clavicle, bisphosphonates.

Osteofibrous dysplasia sometimes referred to as ossifying fibroma is an uncommon nonhereditary, skeletal developmental anomaly. It is considered a fibrovascular defect rather than a true neoplasm [1, 2]. Due to the rarity of this condition and the variation in its progression, surgical treatment is controversial [1, 3]. It is a rare tumor seen in 0.2% of all primary bone tumors [3]. In 1921, the first case of this lesion was reported as congenital osteitis fibrosa by Frangenheim [4], and in 1966, the term was revised by Kempson to ossifying fibroma with a differentiating form of fibrous dysplasia. Finally, the term “osteofibrous dysplasia” was proposed by campanacci in 1976 [5]. This lesion is usually identified in second-decade males before puberty. As opposed to long bones, these pathologies are commonly seen in the craniofacial bones rather than in long bones. Among long bones, these lesions are mostly found in the lower third tibia or fibula as a painless swelling [6, 7, 8]. Usually, surgery will be done after skeletal maturity if required, and it mostly needs marginal excision and bone grafting [9, 10]. We report a case of osteofibrous dysplasia mimicking osteomyelitis in an 11-year boy who was successfully treated conservatively with bisphosphonates.

An 11-year-old boy presented with complaints of pain (VAS score 6) and swelling over his left clavicle and was unable to do overhead abduction following a fall while playing 2 years back. Initially, the patient was diagnosed with a left clavicle fracture and was treated conservatively. The pain subsided after 3 months. The patient had re-injury after 6 months, following which pain and swelling of the left clavicle were gradually progressive. On examination, diffuse swelling extending from the sternal end to the lateral end of the left clavicle was present, which was tender, bony-hard in consistency, and non-mobile, skin over the swelling was pinchable, and no local rise of emperature, no scars, or sinus. No axillary lymph nodes were palpable. The range of movements of the left shoulder was painful and terminally limited. The Oxford shoulder score was calculated and found to be 23. The plain radiograph showed an expansile lesion with diffuse periosteal thickening extending from the medial end to the lateral end of the clavicle with thinning out of the cortex and well-defined margins (Fig. 1). MRI of the left clavicle shows diffuse marrow edema with extensive destructive lysis of the entire shaft of the left clavicle seen with adjacent periosteal reaction and surrounding soft-tissue edema. Expansion of the midshaft of the clavicle with extensive sclerotic changes and permeative destruction was seen (Fig. 2).

Osteofibrous dysplasia, usually in radiographs, shows a lytic lesion centered in the tibial cortex with a lobular-to-bubbly appearance, often with sclerotic margins without any soft-tissue extension or periosteal reaction [5, 8].

We reported a rare case of osteofibrous dysplasia arising in the clavicle of an 11-year-old boy who was treated with bisphosphonates successfully. Osteofibrous dysplasia is uncommonly seen in the clavicle, and if it is seen, it may mimic osteomyelitis clinically. It should be differentiated from other lesions by radiological, histopathological, and immunohistochemistry findings.

Intravenous bisphosphonates are safe, effective, and non-invasive; so it may be one of the better options to manage osteofibrous dysplasia conservatively.

References

- 1.Fletcher CDM, Bridge JA, Hogendoorn PCW, et al. WHO classification of tumours of soft tissue and bone. 4th ed. Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), 2013, pp. 343–355. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abraham VT, Marimuthu C, Subbaraj R, et al. Osteofibrous dysplasia managed with extraperiosteal excision, autologous free fibular graft and bone graft substitute. J Orthop Case Rep 2015; 5(1): 41–44. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yoshida S, Watanuki M, Hayashi K, Hosaka M, Hagiwara Y, Itoi E, Hatori M, Hitachi S, Watanabe M. Osteofibrous dysplasia arising in the humerus: A case report. Rare Tumors. 2018 Nov;10:2036361318808852. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Campanacci M. Osteofibrous dysplasia of long bones. A new clinical entity. Ital J Orthop Traumatol 1976; 2(2): 221–237. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Johnson LC.Congenital pseudoarthrosis, adamantinoma of long bone and intracortical fibrous dysplasia of the tibia. J Bone Joint Surg 1972;54A: 1355. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ishida T, Iijima T, Kikuchi F, Kitagawa T, Tanida T, ImamuraT, et al. A clinic opathological and immunohistochemical study of osteofibrous dysplasia, differentiated adamantinoma, and adamantinoma of long bones. Skeletal Radiol 1992;21:493-502. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ozaki T, Hamada M, Sugihara S, Kunisada T, Mitani S, Inoue H. Treatment outcome of osteofibrous dysplasia. J Pediatr Orthop B 1998;7:199-202. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang JW, Shih CH, Chen WJ. Osteofibrous dysplasia (ossifying fibroma of long bones). A report of four cases and review of the literature. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1992;235-43. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee RS, Weitzel S, Eastwood DM, Monsell F, Pringle J, Cannon SR, et al. Osteofibrous dysplasia of the tibia. Is there a need for a radical surgical approach, J Bone Joint Surg Br 2006;88:658-64. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hahn SB, Kim SH, ChoNH, Choi CJ, Kim BS, Kang HJ. Treatment of osteofibrous dysplasia and associated lesions. Yonsei Med J 2007;48:502-10. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grabias SL, Campbell CJ. Fibrous dysplasia. OrthopClin North Am 1977;8:771-83. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Most MJ, Sim FH, Inwards CY.Osteofibrous dysplasia and adamantinoma.J Am AcadOrthopSurg 2010;18:358-66. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Park YK, Unni KK, McLeod RA, Pritchard DJ.Osteofibrous dysplasia: Clinicopathologic study of 80 cases. Hum Pathol 1993;24:1339-47. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Suresh S, Saifuddin A. Unveiling the ‘unique bone’: A study of the distribution of focal clavicular lesions. Skeletal Radiol 2008;37:749-56. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bjorkstén B, Boquist L. Histopathological aspects of chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1980;62:376-80. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Campanacci M, Laus M. Osteofibrous dysplasia of the tibia and fibula. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1981;63:367-75. [Google Scholar]