Observation of a patient’s gait can provide vital clues for diagnosing certain spinal disorders, At the same time, disorders of hip and sacroiliac joint can also cause such gait alterations and confound the clinician.

Dr. Shailesh Hadgaonkar Spine and Neuroscience Unit, Sancheti Hospital, Pune, Maharashtra, India. E-mail: drshadgaonkar@gmail.com

The success and capability of surgeons are more often than not measured in metrics that directly stem from their operative work – such as the number of cases they operate, the complexity of these cases and the outcomes of their surgeries, particularly from a patient’s perspective. What goes unnoticed and underemphasized, particularly in modern surgical practice, is that surgeons are also required to be astute clinicians in the first place. The ability to wean out the most important details from a patient’s story, to detect the most appropriate clues that the patient’s body gives us, and to interpret these details and clues and string together a provisional clinical diagnosis is a skill that must be celebrated and valued as much as a surgeon’s skills with the knife and other surgical tools. In this short review, we attempt to discuss and leave the readers with some important learning points regarding how alterations in a patient’s gait – namely, limp, list, and lurch – can provide vital information about the underlying cause in the context of spinal disorders. While the lower limbs execute the “dynamic” part of the gait cycle, the spinal column acts as a trunk stabilizer [1]. Impairment in gait and locomotion is a frequent complaint of patients seeking medical attention from spine surgeons – typically as “difficulty in walking,” “limitation of walking distance,” “shifting of body toward one side,” or “imbalance while walking.” For spine surgeons, identifying the alteration in gait and possessing a knowledge of the potential causes behind each kind of gait alteration can help in formulation of a provisional diagnosis, ordering a more focused list of investigations that is consistent with an appropriate diagnostic approach and ruling out confounding causes from the hip, sacroiliac joint, abdominal and pelvic viscera, and the rest of lower limbs. Such a practice is important to ameliorate the anxiety of the patients and reduce the healthcare costs – both of which arise from ordering of unnecessary investigations and following an incoherent diagnostic approach.

Limp

Limp is a broad, encompassing term that is used even by laypersons for any abnormality in gait or locomotion. For clinicians, a patient presenting with or reporting a “limp” usually refers to an antalgic gait pattern which can be noted clinically as a shortening of the stance phase of the gait. Normal gait is a cyclical and symmetric process – 60% of the time is spent in the stance phase and 40% of the time is spent in the swing phase of the gait [2]. Antalgic gait is secondary to pain – the source of this pain may be located in the spine or anywhere in the lower limbs. This adaptive mechanism avoids weight transmission through the painful area and minimizes the recruitment of muscles and joints that may be a part of the pathology. The clinician’s task, when faced with such a situation, is to locate the source of pain anatomically – this demands a thorough examination of the spine and lower limbs. The precise etiology – infection, inflammatory, traumatic, or neoplastic – can be further elucidated based on the pattern, severity, character, and chronicity of pain. Eliciting tenderness while looking at the patient’s face for wincing is a classical way to identify the site of pain – however, tenderness may not always guide the clinician to the source of pain because of the complex overlapping referral patterns of pain from intra-abdominal, intra-thoracic, and retroperitoneal causes. Afflictions of the hip joint and sacroiliac joint can also manifest with pain distribution patterns similar to spinal afflictions. A study by Fischer and Beattie reported a spinal etiology in 1.2% of cases among 243 children presenting to emergency with an acute atraumatic limp [3].

Limp in association with spinal disorders generally can present with one of the following forms:

- A classic antalgic gait with shortening of the stance phase for one particular limb is seen with distal and asymmetric involvement of the spine with a side predilection – examples are paracentral lumbar disc herniations, unilateral sacroilitis, and osteoid osteoma of the spine

- A more central pathology in the spinal column – such as infectious spondylodiscitis and tumors of the vertebral body lead to the so-called cautious antalgic gait where the patient walks with short steps and tries to keep the spine stiff and as immobile as possible. The normal rhythmic flexion-extension of the spine as a part of the normal gait, in such cases, is missing.

- More severe pain – seen with acute vertebral fractures of osteoporotic spine or infection/neoplasm leading to a pathological collapse – is typified by a complete refusal to walk. The patient is bed or wheelchair-bound and even side-turning in bed is painful.

Non-antalgic limp is due to an underlying neuromuscular cause – this may be the high-steppage gait seen with foot-drop due to affliction of the L4 nerve root, spastic gait seen with upper motor neuron involvement of the spinal cord in cervical or thoracic compressive myelopathy or the very commonly encountered stooped gait with neurological claudication seen in degenerative lumbar canal stenosis. Distinguishing between normal and pathological gaits in the elderly may be challenging – the elderly possess a shorter and broad-based stride with decreased walking velocity which may be confused with altered gait patterns seen in neurological disorders such as parkinsonism, cerebellar ataxia, and other sensorimotor neuropathies.

List

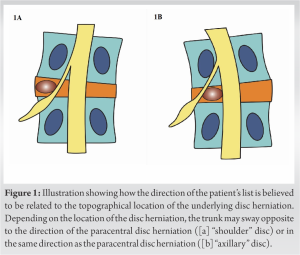

Swaying of the trunk toward one side is noted with certain spinal disorders. When a scoliotic curve of the spine is noted in association with the truncal shift, the gait alteration is known as a “list.” List is a gait alteration classically seen in patients with lumbar disc herniation. Lumbar disc herniation is ubiquitous – it affects 2–5% of the world’s population annually [4]. Sciatic scoliotic list is a truncal shift caused due to a non-structural, short lumbosacral curve with a long thoracic curve and a relatively straight sagittal profile [5]. The incidence of a sciatic list has been reported to be 13%–17% in adult patients with lumbar disc herniation [6, 7]. Classically, it has been hypothesized that when the herniation is lateral to the nerve root (a “shoulder” disc herniation), the list is to the opposite side of the herniation whereas when the herniation is medial to the nerve root (the “axillary” disc herniation), the list is toward the side of the herniation – this has been believed to alleviate the nerve root irritation in accordance with the topographical location of the disc herniation (Fig. 1) [8]. However, more recent reports have challenged this assumption, having found that the sciatic scoliotic list was likely to occur with the convexity to the symptomatic side of disc herniation irrespective of the topographic location of the herniated disc [7, 9].

Lurch

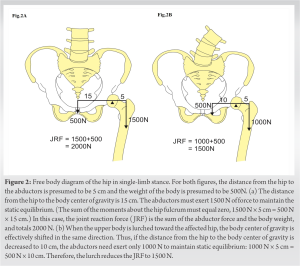

Lurch is characterized by a shifting of the upper torso with a drop of the contralateral hemipelvis during the single-limb stance phase of the symptomatic side. This gait pattern is also referred to as the abductor lurch, coxalgic gait, and when associated with the typical dropping of the hemipelvis – as the Trendelenburg gait. In the context of spinal disorders, lurch can be seen on account of abductor weakness due to L5 radiculopathy. The shifting of the upper torso toward the affected side (the side with weak abductors) seen as a part of the lurch brings the center of gravity closer to the hip joint, decreasing the abductor force required to maintain a level pelvis. During the single-stance phase, the hip joint acts as a fulcrum – with the body weight on one side and the force of the abductors on the other side (Fig. 2). The two forces acting on this fulcrum must balance each other to maintain a static equilibrium during the single-limb stance [10].

- Observation of gait alteration in patients can provide vital clinical clues to the underlying spinal disorders

- A systematic history taking and a comprehensive physical examination are necessary to rule out potential confounding factors such as intra-articular or extra-articular pathologies of the hip joint or sacroiliac joint pain

- Patients who “limp” usually have a pain generator – clinical examination and investigations must be directed towards finding the source of this pain

- Patients who have a “list” or who “lurch” usually have a symptomatic lumbar disc herniation which needs to be addressed.

References

- 1.Garg B, Gupta M, Mehta N, Malhotra R. Influence of etiology and onset of deformity on spatiotemporal, kinematic, kinetic, and electromyography gait variables in patients with scoliosis-a prospective, comparative study. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2021;46:374-82. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kharb A, Saini V, Jain YK, Dhiman S. A review of gait cycle and its parameters. IJCEM Int J Comput Eng Manag 2011;13:78-83. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fischer SU, Beattie TF. The limping child: Epidemiology, assessment and outcome. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1999;81:1029-34. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schroeder GD, Guyre CA, Vaccaro AR. The epidemiology and pathophysiology of lumbar disc herniations. In: Seminars in Spine Surgery. Netherlands: Elsevier; 2016. p. 2-7. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wu W, Chen Y, Yu L, Li F, Guo W. Coronal and sagittal spinal alignment in lumbar disc herniation with scoliosis and trunk shift. J Orthop Surg 2019;14:264. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim R, Kim RH, Kim CH, Choi Y, Hong HS, Park SB, et al. The incidence and risk factors for lumbar or sciatic scoliosis in lumbar disc herniation and the outcomes after percutaneous endoscopic discectomy. Pain Physician 2015;18:555-64. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhao Y, Qi L, Ding C, Quan S, Xu B, Yu Z, et al. Characteristics of sciatic scoliotic list in lumbar disc herniation. Global Spine J 2022;21925682221126124. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Finneson BE. Low Back Pain. United States: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Matsui H, Ohmori K, Kanamori M, Ishihara H, Tsuji H. Significance of sciatic scoliotic list in operated patients with lumbar disc herniation. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1998;23:338-42. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lim MR, Huang RC, Wu A, Girardi FP, Cammisa FP Jr. Evaluation of the elderly patient with an abnormal gait. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2007;15:107-17. [Google Scholar]